Dyspnea is one of the most common and anxiety-provoking symptoms in oncology and palliative care patients. Always consider causal therapy options first. In addition to and instead of causal therapy, a combination of drug and non-drug measures is useful. The best evidence regarding symptom relief is for opiates; no benefit has been demonstrated for oxygen administration, although administration is often subjectively perceived as relieving symptoms.

Respiratory distress is one of the most common, if not the most common, symptom in advanced tumor disease [1]. It is also the symptom that causes the most anxiety for sufferers and their families. Already having to endure pain is feared by many more than death, but even worse is the idea of suffocation.

However, dyspnea is also the symptom that is probably the most difficult to assess objectively. Like pain, it is a subjective sensation (“shortness of breath is what the patient says it is”). At the same time, objective clinical findings (tachypnea, use of respiratory support muscles) or laboratory results (O2 saturation, anemia) are available, but often correlate poorly or even not at all with subjective severity. Crushing respiratory distress in a hyperventilation attack is not uncommonly associated with 99% saturation. Conversely, there are patients who report no respiratory distress but never get above 90% with saturation.

What is standard?

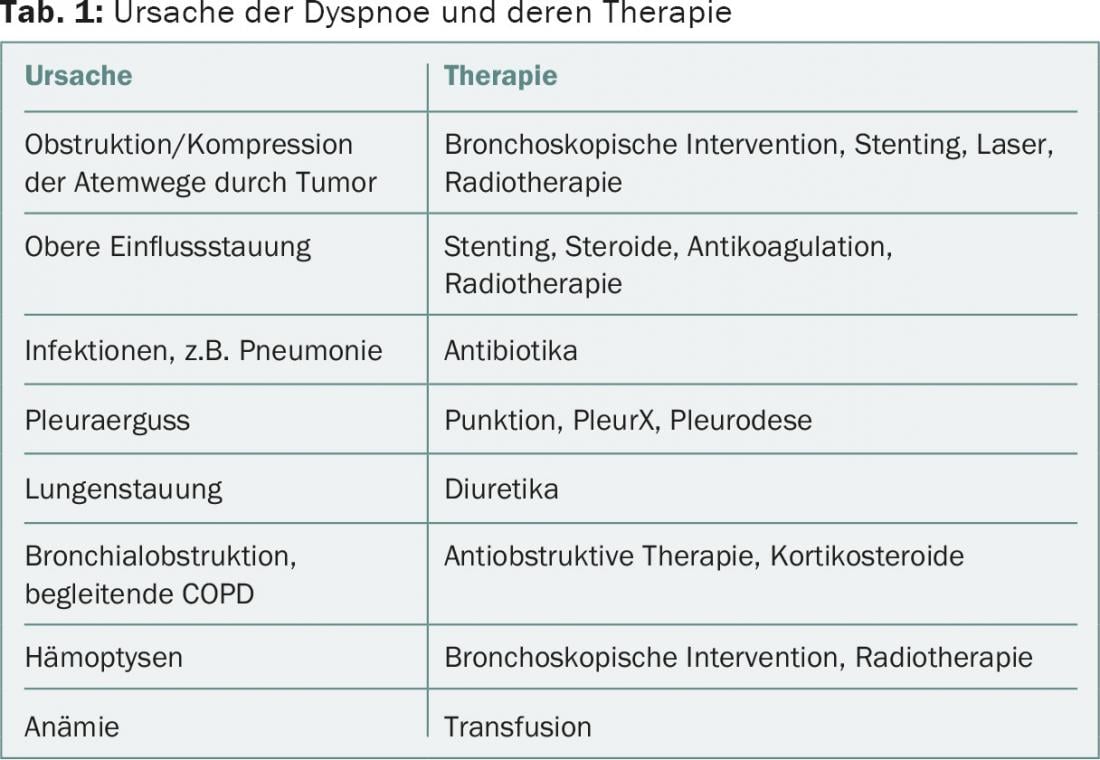

As always when we deal with symptoms, the medical task is to look for the cause and treat it if possible. Table 1 provides an overview of the most important causes of dyspnea in palliative patients and their causal therapy.

Because dyspnea is a very complex symptom, one therapeutic measure alone is rarely sufficient for a satisfactory solution in severe dyspnea. Therefore, a combination of general measures, non-drug and drug interventions is usually necessary in addition to or, in the case of a very advanced disease process, instead of causal therapy [2].

General measures

Adequate positioning and comfortable clothing are important for the patient with severe respiratory distress. Even a well-ventilated room or an open window can go a long way.

The activities of daily living, personal hygiene, eating, but also examinations, therapies and visits should be well distributed throughout the day (“energy banking”, rhythm saves energy).

One’s own attitude in the encounter with the person concerned must be very conscious. If I breathe calmly myself, then this also has a calming effect, but if I allow myself to be “infected” by restlessness or tension, then a vicious circle develops. Probably nowhere are the phenomena of transference and countertransference so openly revealed as in dyspnea. So it’s worth stopping for a moment in front of the room, to come to rest. Speaking in a quiet voice in the room, making short sentences, allowing pauses. At best, just “being there” and enduring the helplessness.

Information about the phenomenon of respiratory distress is also one of the non-specific measures, as is support for relatives and their involvement or, if necessary, their training.

Non-medicinal measures

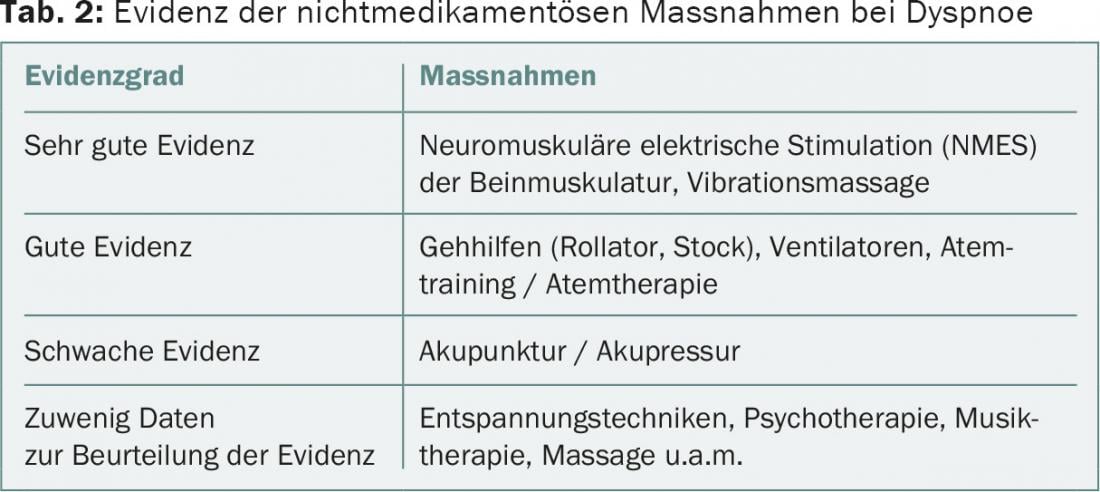

In addition, there are a number of specific measures that have been studied to varying degrees and therefore have very different levels of evidence (Table 2).

Despite the best evidence, hardly anyone knows about neuromuscular electrical stimulation of the leg muscles (NMES); while relaxation techniques, psychotherapy, music therapy, and massage are widely used with good experience, although conclusive studies are lacking [3].

Mention should be made of the use of a hand ventilator, a very simple and cheap measure, on which a small study was also made, demonstrating subjective relief of respiratory distress [4].

Also very popular are complementary measures from aromatherapy such as a restrained scenting of the room (angelica root, lavender, myrtle, thyme, incense) or rubs and other external applications based on essential oils.

Drug therapy

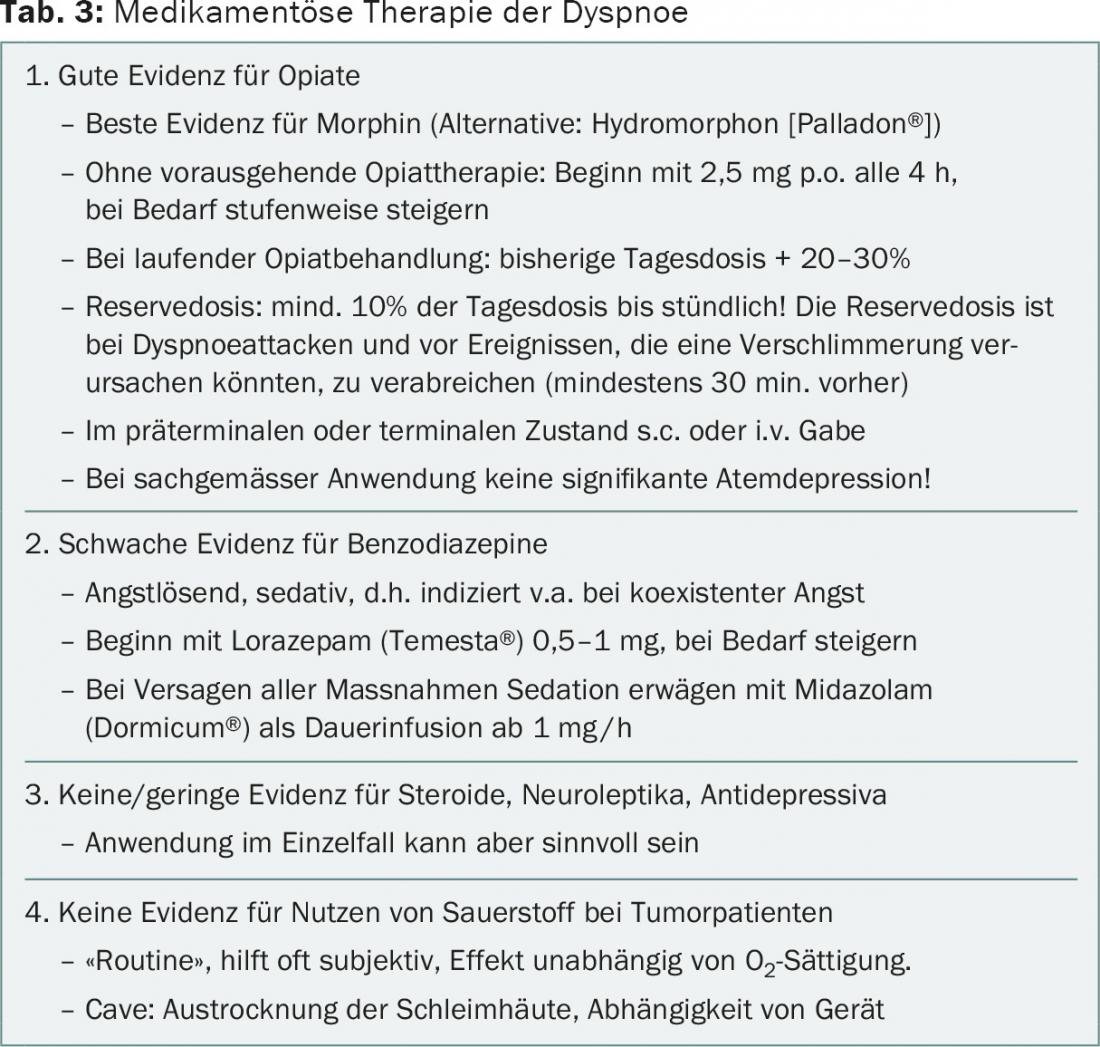

The evidence for drug therapy for dyspnea is presented in Table 3 . Drugs of choice today are opiates, primarily morphine [5]. Because of their respiratory depressant effects, they were contraindicated until a few years ago for all respiratory problems except terminal. However, recent studies show that respiratory depression has no clinical significance when dosed correctly and that properly dosed morphine therapy does not shorten life [6]. Dosage recommendations can also be found in Table 3.

The evidence for benzodiazepines is much worse. They are usually prescribed in addition to opiates when a strong emotional component of dyspnea is present or suspected. In this respect, too, recommendations have been revised in recent years since it could be shown that the respiratory depressive effect of benzodiazepines is not associated with a shortening of life except in overdose [6]. Also with regard to oxygen administration, a lot has changed in the last few years due to recent studies [7]. Whereas in the past oxygen was always included both in respiratory distress and in the terminal phase except when there was a risk of CO2 retention, today it is only recommended if the patient subjectively benefits from it.

Cough

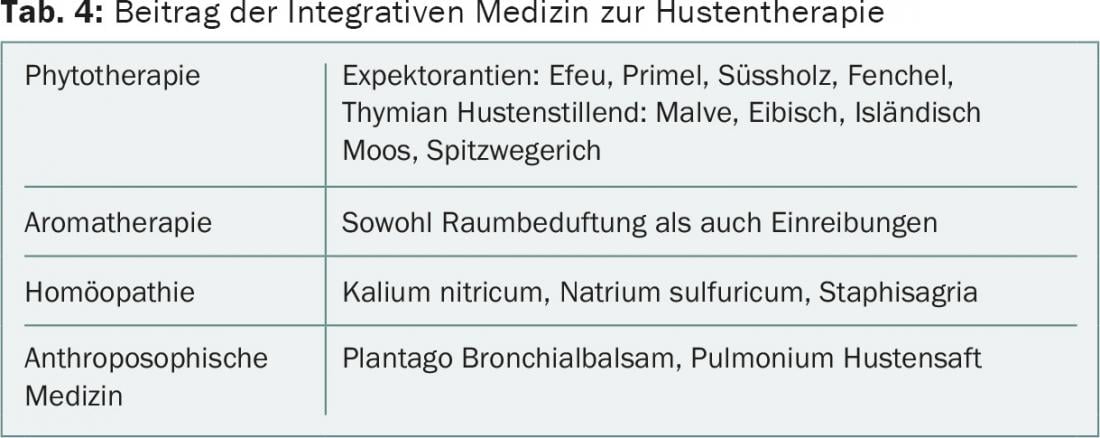

Cough is also an important symptom in tumor patients, often but not always associated with dyspnea. For the symptomatic therapy of cough in advanced disease, a combination of non-pharmacological and pharmacological measures is also useful, whereby special reference should also be made to the measures from the field of integrative medicine (Tab. 4) [8]. Overall, the evidence base for cough is much poorer than for dyspnea [9].

Principles of cough therapy

Basically, two somewhat opposing principles are available, which are used depending on the symptoms and the situation:

- Protussives: if mucus is prominent, protussives may be helpful to liquefy and loosen the tough mucus and promote expectoration. Tough mucus can be liquefied e.g. with acetylcysteine (Fluimucil®) or altogether with an improvement of hydration. Inhalation with NaCl or e.g. thyme tea, physiotherapy as well as various essential oils and herbal substances are used complementarily to improve mucus clearance and expectoration.

- Antitussives: centrally acting antitussives such as dextrometorphan, morphine, and codeine suppress the cough center. Inhaled local anesthetics act as peripheral antitussives but may cause bronchospasm. For suppression of the cough reflex, the best evidence is for opiates, especially morphine and codeine, but also for dextrometorphan, which has fewer side effects. Peripheral antitussives may be tried in the form of inhaled local anesthetics.

Terminal rattle

As a special case of dyspnea, the so-called carching or terminal rales are sometimes treated. This is noisy breathing caused by air turbulence in the secretions that accumulate in the oropharynx and bronchial branches of terminal patients when they are no longer able to eliminate them by coughing or swallowing. Although it is questionable whether carping is associated with dyspnea, the burden on family members and staff always raises the question of adequate management.

Informing relatives about the nature of carping has proven to be the most important measure. Suction is not recommended because the stimulus of the suction catheter usually provokes more secretion than could be aspirated. Fluid restriction is useful, and a trial of diuretics is also useful if overhydration is suspected. Anticholinergics, e.g., Buscopan® or atropine, are used to inhibit secretion, but the evidence is modest and use is recommended only when family members or caregivers are burdened by the noise [10].

Literature:

- Teunissen SC, et al: Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007; 34: 94-104.

- Bausewein C, et al: Shortness of breath and cough in patients in palliative care. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2013; 110(33-34): 563-72.

- Bausewein C, et al: Non-pharmacological interventions for breathlessness in advanced stages of malignant and non-malignant diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008(2): CD005623.

- Galbraith S, et al: Does the use of a handheld fan improve chronic dyspnea? A randomized, controlled, crossover trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010; 39: 831-8.

- Barnes H, et al: Opioids for the palliation of refractory breathlessness in adults with advanced disease and terminal illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; (3): CD011008.

- Sykes N, et al: The use of opioids and sedatives at the end of life. Lancet Oncology 2003, Vol.4, 312-318.

- Abernethy AP, et al: Effect of palliative oxygen versus room air in relief of breathlessness in patients with refractory dyspnoea: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010; 376: 784-93.

- Huber G, et al: Komplementäre Sterbebegleitung, Haug 2011.

- Wee B, et al: Management of chronic cough in patients receiving palliative care: review of evidence and recommendations by a task group of the Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland. Palliat Med 2012; 26: 780-7.

- Bennett M, et al: Using anti-muscarinic drugs in the management of death rattle: evidence-based guidelines for palliative care. Palliat Med 2002; 16: 369-74.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2016; 4(6): 25-28.