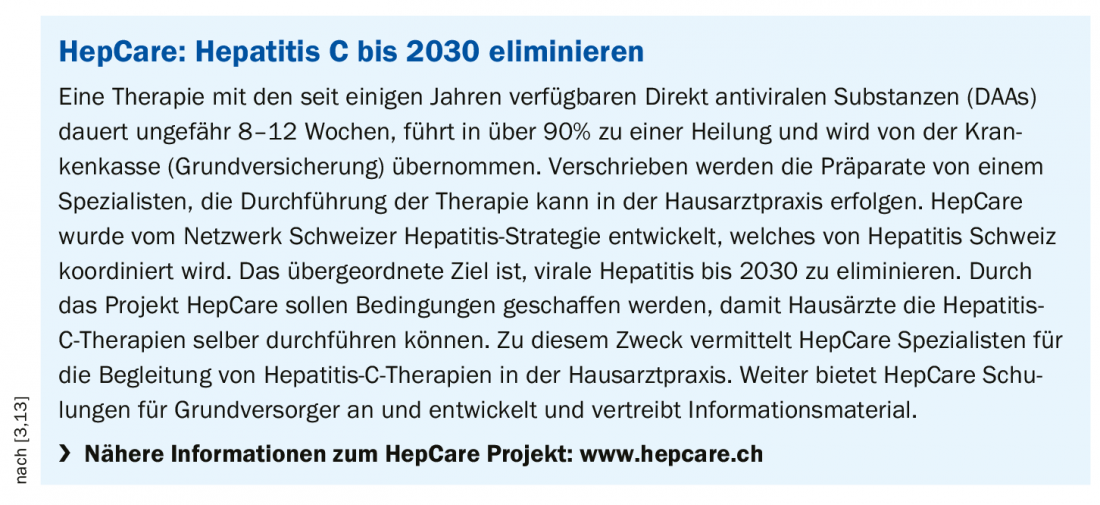

Due to the highly effective antivirals currently available on the market, the chances of cure are very high. However, if left untreated, hepatitis C infection can have serious consequences. The HepCare project launched by Hepatitis Switzerland provides support to primary care physicians to implement the new direct antiviral therapies and raises awareness of the high rate of undiagnosed cases.

For several decades, hepatitis C was considered a viral disease that was difficult to treat with significant side effects. Standard therapy led to successful healing in only about half of the cases. Since 2014, representatives of the so-called “direct acting antiviral agents” (DAA) have been on the market, which have significantly shortened the duration of treatment, show hardly any side effects and have a cure rate of over 90% (Tab. 1).

High number of unreported cases: testing risk groups

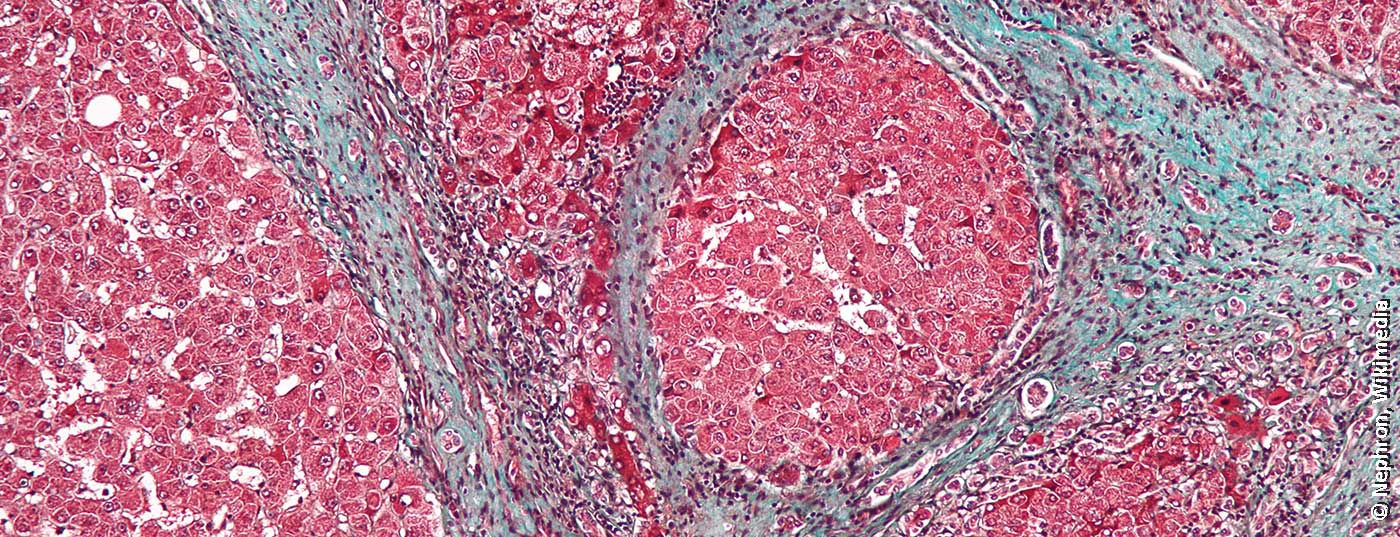

Both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Swiss Hepatitis Strategy aim to eliminate hepatitis C by 2030. Infections as well as mortality and morbidity should be brought close to zero. Model calculations show that this can be done cost-effectively, also for Switzerland [1,2]. However, more efforts are needed to close gaps in coverage when testing for viral hepatitis [3]. The number of undiagnosed cases is high, although test recommendations have been available for years. In many individuals with chronic hepatitis C, symptoms are nonspecific and often misinterpreted. In addition to fatigue, affected individuals include impaired performance, joint pain and digestive problems. If the infectious disease is diagnosed years later, for example as an incidental finding, the liver may already show considerable damage. Timely diagnosis followed by therapy can not only avert secondary diseases and associated costs, but also prevent further spread of the virus.

Most transmissions occurred before the early 1990s, before blood products were tested for hepatitis C and before drug prevention measures took hold. The majority of affected individuals were born between 1950 and 1985, which is reflected in the age distribution of hepatitis C sufferers. In these cohorts, therefore, special attention should be paid to signs of viral hepatitis, for example, as part of check-ups or colon cancer screening, both measures that are frequently performed in these cohorts [5,6]. Consistently screen for hepatitis C in the patient population of individuals with a history of drug use. If the result is negative, a repetition of the test in the following year is recommended [7]. If positive, further investigations and therapeutic measures are indicated [8]. In addition to intravenous drug use, the administration of infected blood products prior to the 1990s and (dental) medical treatments or certain cosmetic procedures (e.g., manicure, pedicure, piercings, or tattoos) performed under hygienically inadequate conditions were significant transmission routes. Infection from an infected mother to the child is also possible. First-generation migrants over 60 years of age from southern Europe, particularly Italy, also have a greatly increased prevalence of hepatitis C compared with the general population [9].

Direct antiviral agents: very high cure rates

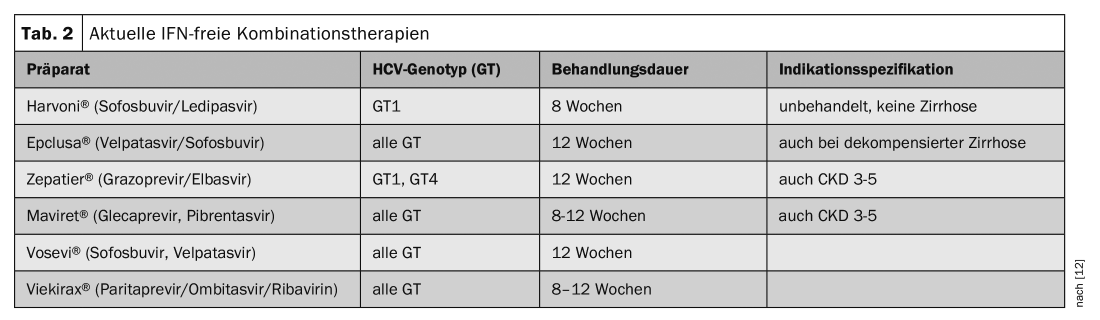

Today, chronic hepatitis C infection is easily curable. Therapy with antiviral drugs lasts 8-12 weeks, leads to cure in over 90% of cases and is covered by basic insurance. With the assistance of a specialist, the therapy can now also be performed in the family doctor’s office. Only the prescription must be made through a specialist. Development and market approval of direct-acting agents (DAAs) represented a breakthrough in treatment options. HCV infection can be cured in >90% today. Indications are chronic infection and extrahepatic manifestations. DAAs are drugs with a new mechanism of action. They intervene directly at different points in the multiplication cycle of the hepatitis C virus. It has been scientifically proven that by combining two or three of these new DAAs from different classes, successful therapy of chronic hepatitis C is possible even without interferon. Various DAAs are available in Switzerland (tab. 1) . The treatment recommendation depends on the degree of liver damage, the symptoms and the risk of infection. An overview of IFN-free combination therapies is provided in table 2. Since 2017, the costs are covered by the health insurance (basic insurance) if there is a corresponding indication.

Literature:

- Mullhaupt B, et al: Progress toward implementing the Swiss Hepatitis Strategy: Is HCV elimination possible by 2030? PLoS One 2018; 13(12): e0209374.

- Blach S, et al: Cost-effectiveness analysis of strategies to manage the disease burden of hepatitis C virus in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly 2019; 149: w20026.

- Hepatitis Switzerland, www.hepatitis-schweiz.ch

- BAG: Substitution-assisted treatment for opioid dependence, revision 2013. www.bag.admin.ch

- Richard JL, et al: The epidemiology of hepatitis C in Switzerland: trends in notifications, 1988-2015. Swiss Med Wkly 2018; 148: w14619.

- Bruggmann P, et al: Birth cohort distribution and screening for viraemic hepatitis C virus infections in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly 2015; 145: w14221

- Bruggmann P, et al. (Hepatitis Switzerland): Closing gaps in viral hepatitis testing. Swiss Medical Journal 2018; 99(3031): 973-975.

- Fretz R, et al: Hepatitis B and C in Switzerland – healthcare provider initiated testing for chronic hepatitis B and C infection. Swiss Med Wkly 2013; 143: w13793.

- Bertisch B, et al: Characteristics of Foreign-Born Persons in the Swiss Hepatitis C Cohort Study: Implications for Screening Recommendations. PLoS One 2016; 11(5): e0155464.

- Swissmedic, www.swissmedic.ch

- Swiss Medical Forum 2015; 15(17): 366-370

- Wedemeyer H: German hepatitis C registry: current evaluations and their consequences. Dtsch Arztebl 2018; 115(27-28), DOI: 10.3238/PersInfek.2018.07.09.001.

- HepCare, www.hepcare.ch

FAMILY PRACTICE 2020; 15(6): 27-28