Immune complex vasculitis is the most common form of vasculitis. One should always ask in diagnosis and therapy whether it is an isolated cutaneous vasculitis or a systemic vasculitis with cutaneous involvement. After exclusion of important vasculitis mimics, the identification and elimination of vasculitis-causing factors and the treatment of the underlying disease, respectively, represent the first and most important therapeutic step.

Vasculitides are a very heterogeneous group of diseases, which can occur in all age groups. In principle, these are inflammatory processes in the vessel walls with subsequent tissue damage to various organs. The skin is one of the most frequently affected organ systems. The clinical spectrum ranges from low-symptomatic, self-limiting vasculitis limited to the skin to life-threatening systemic vasculitis.

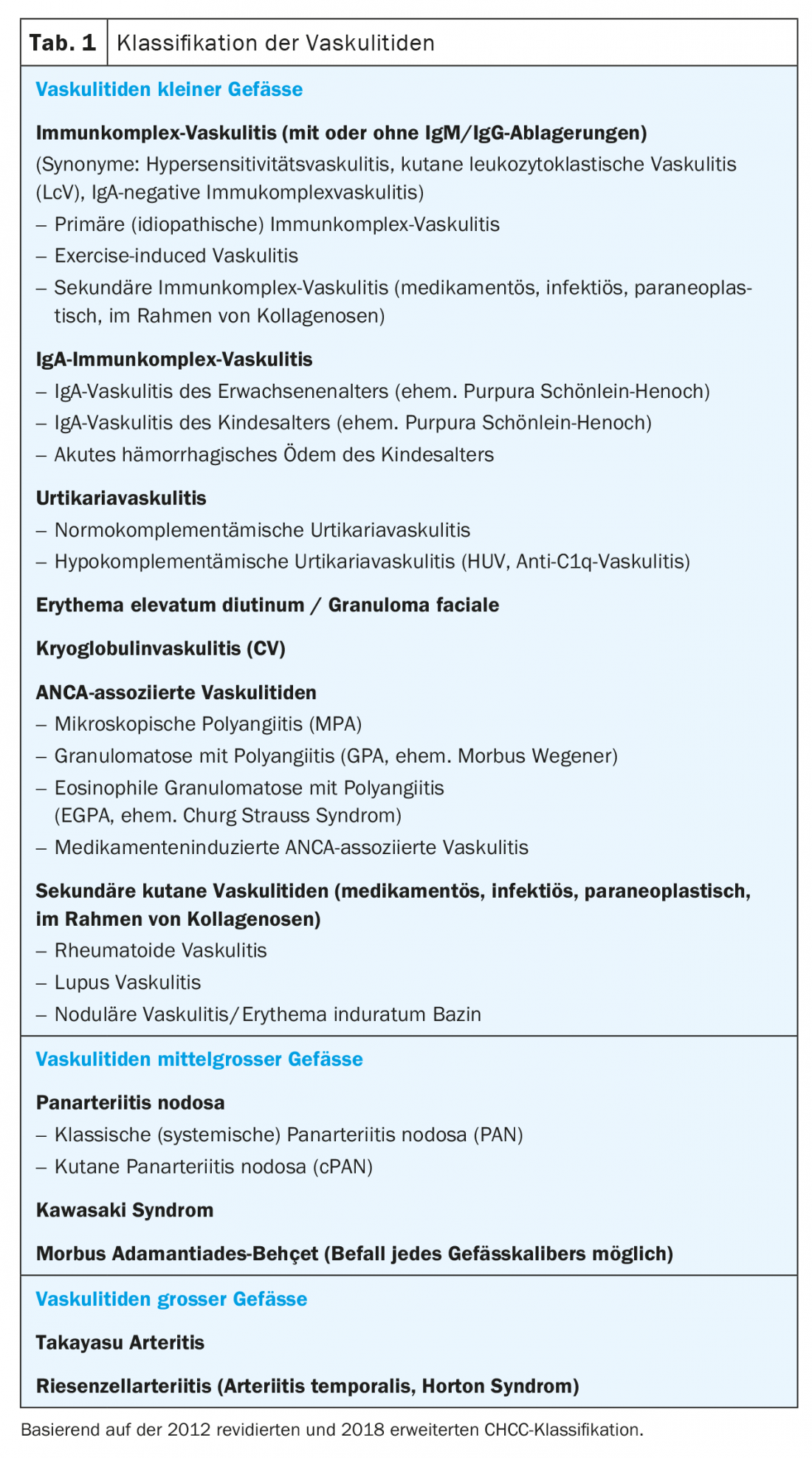

Classification of vasculitides

Unfortunately, a generally valid, comprehensive and clear classification of vasculitides and especially cutaneous vasculitides does not exist. On the contrary, different classification systems and not always uniformly used nomenclatures make it difficult for the clinician to keep track. For example, the descriptive term “leukocytoclastic vasculitis” is often used synonymously with mild cutaneous vasculitis, although the histologic findings of leukocytoclastic vasculitis in various vasculitis types incl. ANCA-associated systemic vasculitis may be present.

In clinical practice, the most common classification is according to the size of the vessels mainly affected (classification and nomenclature according to Chapell Hill Consensus Conference 1992, revision 2012 and addition for cutaneous vasculitides 2018). A distinction is made between small, medium and large vessels. Small vessels are arterioles, capillaries and post-capillary venules. In the skin, these vessels are found in the upper and middle dermis. The medium-sized vessels include the small arteries and veins in the deep dermis and subcutis. By definition, great vessels are larger arteries and veins to which an anatomical name is assigned. Fortunately, the 2018 publication focuses on cutaneous vasculitides for the first time. In addition, vasculitides confined exclusively to the skin are also defined. A detailed compilation of various vasculitides including their subtypes and special forms is shown in Table 1.

Vasculitides with cutaneous manifestations are predominantly small vessel vasculitides, medium vessel vasculitides, or vasculitides affecting both calibers of vessels. Immune complex vasculitis with perivascular immune complex deposits (syn. hypersensitivity vasculitis, cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis in the narrower sense) from the group of cutaneous small vessel vascul-li-tides, is by far the most common form of vasculitis and usually remains confined to the skin.

Causes and pathogenesis

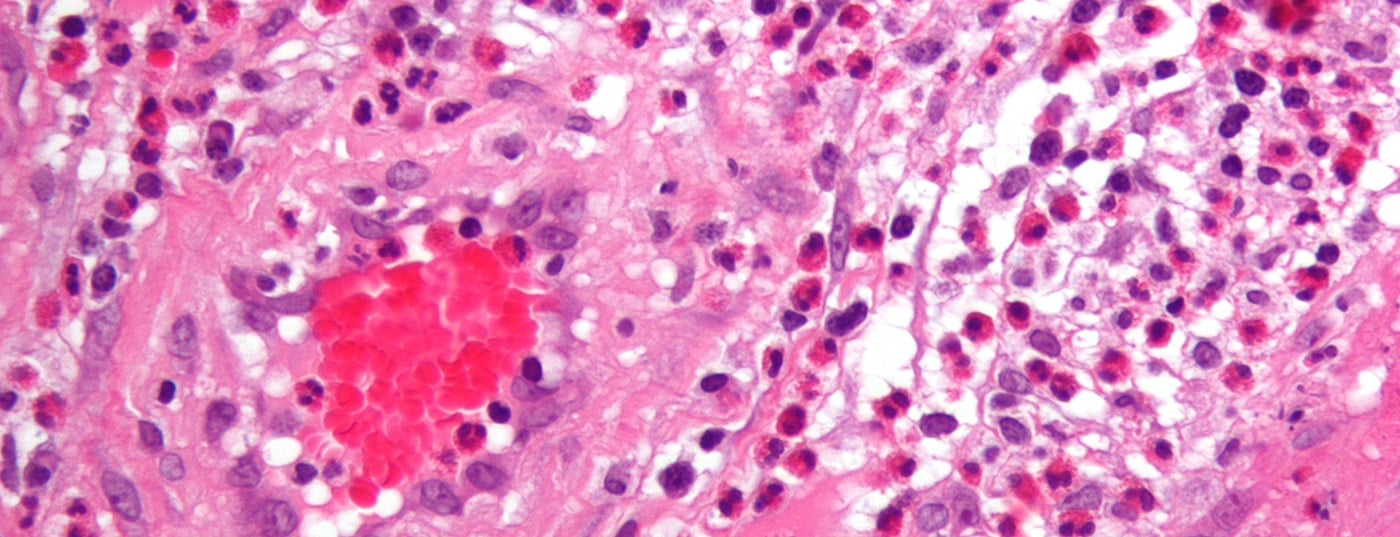

A central pathomechanism of many vasculitides and especially of immune complex vasculitides is the formation of immune complexes (antigen-antibody-complement complexes). The immune complexes are deposited in particular in the post-capillary venules and trigger an inflammatory reaction in the vessel walls and the immediate surroundings via complement activation and mast cells. Immigrating neutrophil granulocytes release proteases and oxygen radicals and further damage the tissue. The neutrophil granulocytes subsequently disintegrate, leaving nuclear debris (leukocytoclasia). Rarely, vasculitis can be caused without the presence of immune complexes. Examples include bacteremia or anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), which lead to direct stimulation of neutrophil granulocytes, causing vascular damage (so-called pauci-immune vasculitides).

The list of potential vasculitis causes (antigens) is long. Both exogenous antigens, such as drugs or infectious agents, and endogenous antigens, in the context of autoimmune and neoplastic diseases, are known and can be detected as causes in about half of vasculitides.

Clinical presentation

The type and size of the affected vessels determine the clinical picture of vasculitis on the skin and other organ systems. Simultaneous involvement of multiple vessel types and caliber is not uncommon, which explains the wide clinical spectrum.

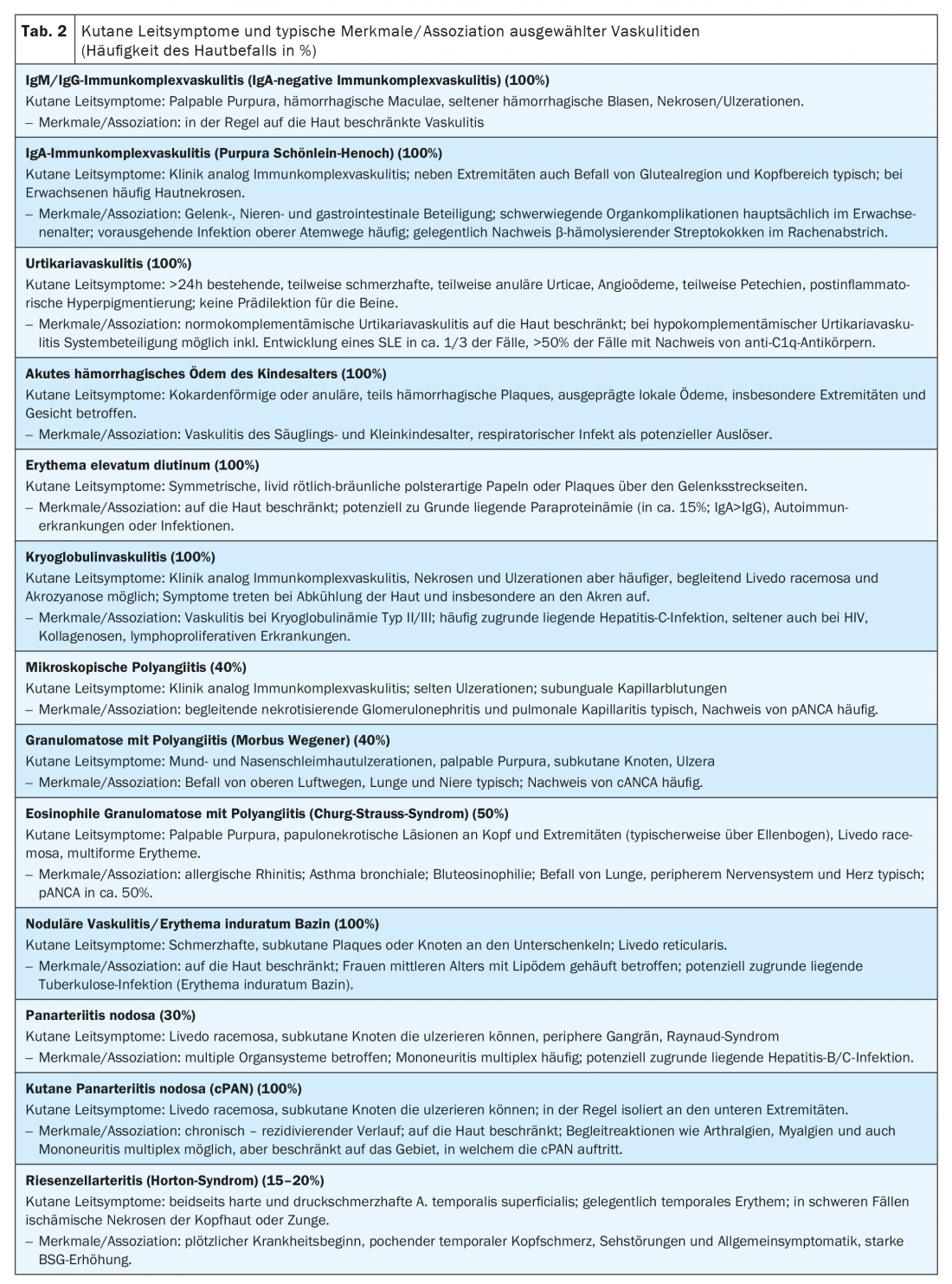

The typical clinical presentation of immune complex vasculitis is a palpable, non-dispersible purpura beginning in the lower legs and ascending proximally. The skin changes increase in intensity towards the distal end due to the hydrostatic pressure in the vessels. At the beginning of the disease, the findings may be macular or urticarial and sometimes still pushable away. Full-blown hemorrhagic papules, blisters, and necrosis may occur. The clinical picture changes with increasing size of the affected vessel caliber from small-spotted and petechial macules to palpable purpura to subcutaneous nodules and ulcerations.

The vasculitic papules often do not cause any discomfort, occasionally there is a slight burning sensation or itching. Vasculitic necrosis and ulceration, on the other hand, are very painful. Systemic concomitant manifestations of cutaneous vasculitis may include general symptoms such as fever or arthralgias.

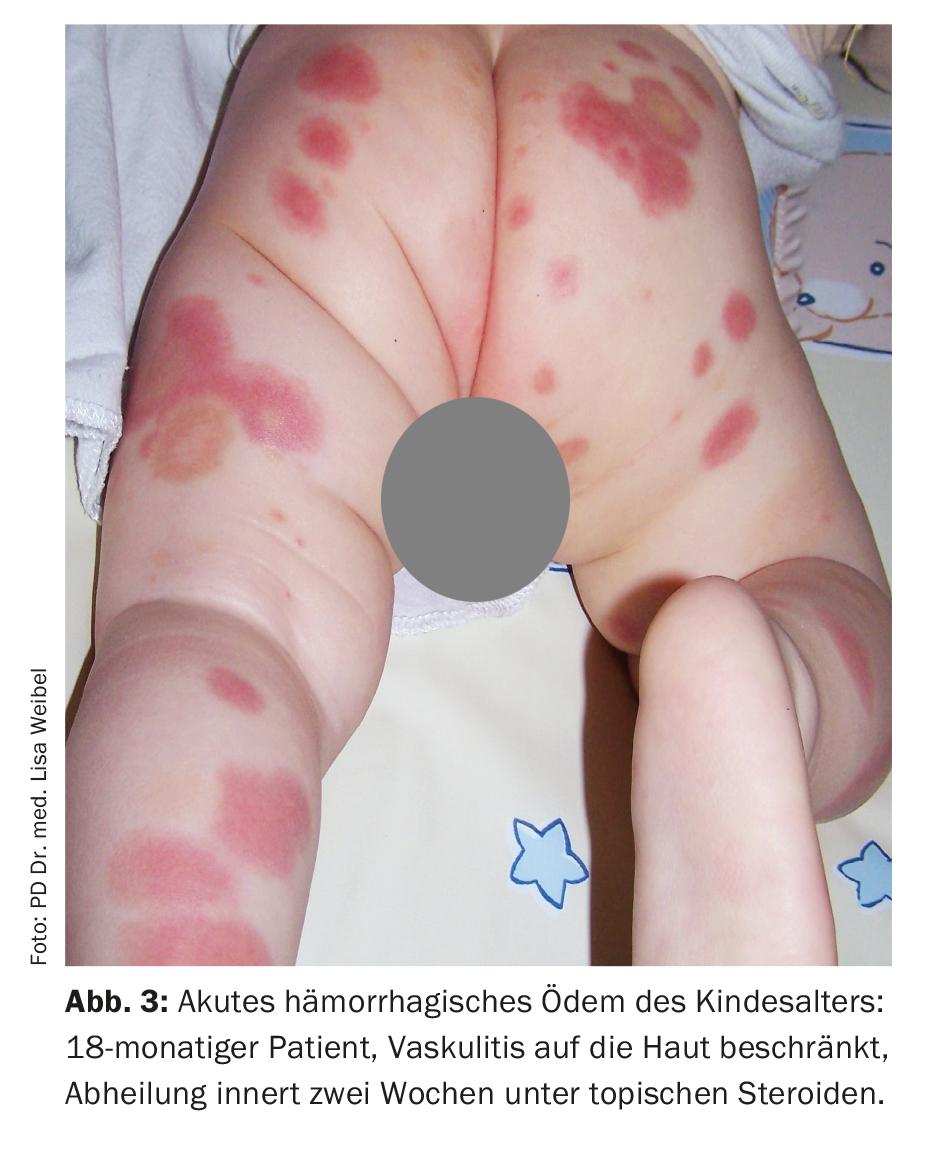

Examples of other cutaneous manifestations in vasculitis include urticaria, angioedema, multiforme erythema, livedo racemosa, Raynaud’s syndrome, or peripheral gangrene. Figures 1-4 show different clinical presentations of vasculitides. Table 2 provides an orienting overview of cutaneous leading symptoms of selected vasculitides.

Diagnostic steps

When clarifying and treating a vasculitis, the treating physician should always ask himself whether it is an isolated cutaneous vasculitis or a systemic vasculitis with cutaneous involvement and adjust his diagnostic and therapeutic procedure accordingly.

The goals of diagnostics are

- confirming the diagnosis and classification of vasculitis,

- Exclusion of important differential diagnoses (vasculitis mimics such as infectious diseases, embolic diseases, vasculopathies, or coagulation disorders),

- Search of potential vasculitis triggers and

- Identify affected organ systems and complications.

Achieving these goals requires knowledge of the types of vasculitis, their clinical characteristics, possible triggers, and corresponding organ involvement. Although many cases are the presence of self-limiting small vessel vasculitis confined to the skin, and a trigger cannot be identified in about half of cases, it is worthwhile to go through the individual diagnostic points to identify more serious forms of vasculitis and vasculitis mimics early.

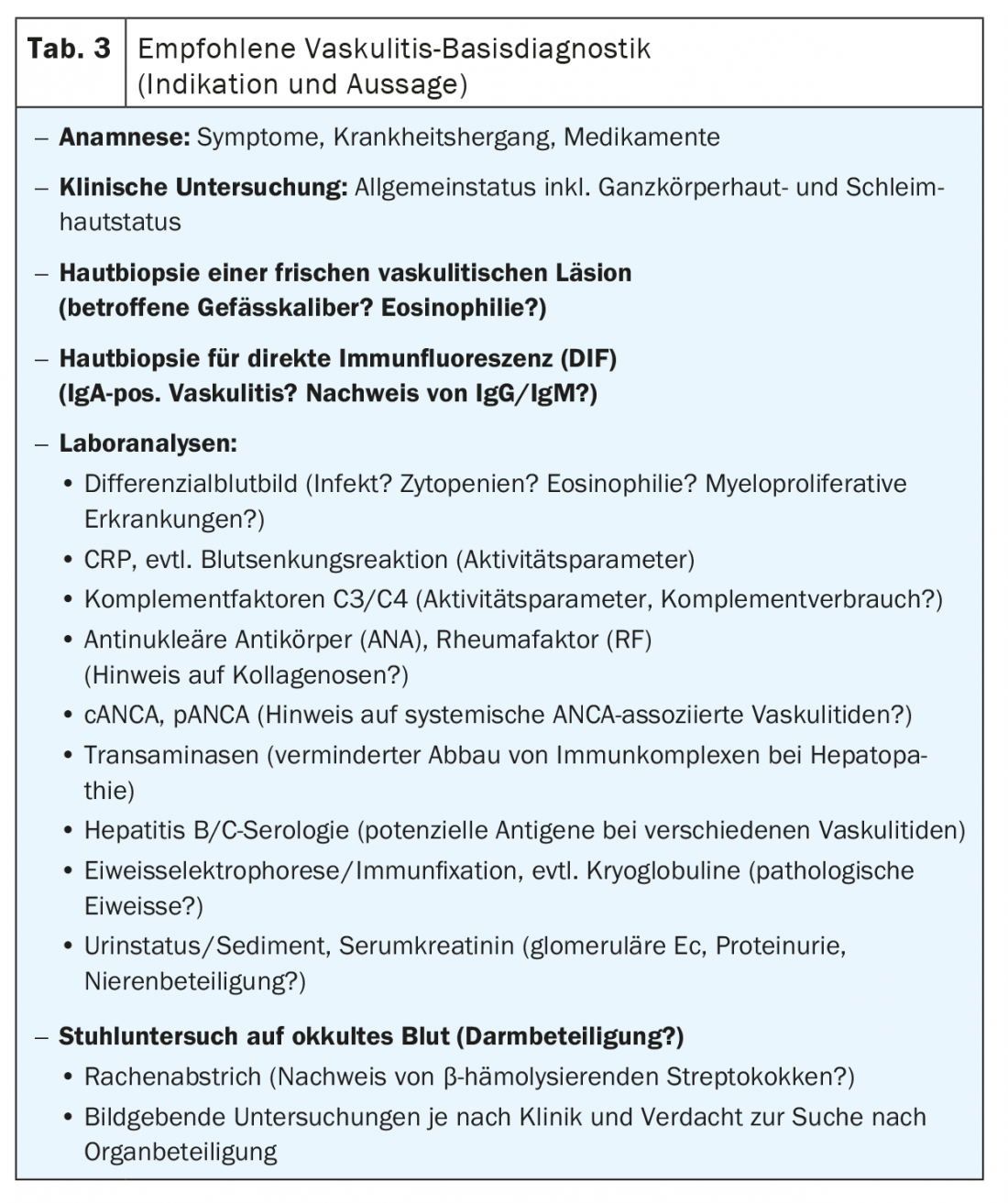

Anamnesis and clinical examination are the first steps in the evaluation of vasculitis. In order to meet all the objectives of vasculitis diagnostics, the number of recommended examinations is relatively high (Tab. 3). The suspected clinical diagnosis is confirmed by skin biopsy. Biopsy is performed on a skin lesion that is as fresh as possible and not necrotic. In order to reach deeper vessels located in the subcutis, it is recommended to take a narrow spindle biopsy that extends into the subcutis. Part of the excisate (longitudinally split spindle) can be used for direct immunofluorescence (DIF). Histologic characteristics of many small vessel vasculitides include a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate with neutrophil and eosinophil granulocytes, disintegrating neutrophil granulocytes with nuclear debris (leukocytoclasia), fibrinoid vessel wall swelling and erythrocyte extravasation, and in DIF, evidence of immunoglobulin deposits (IgM, IgG, IgA) perivascularly. It should be noted that IgM and IgG are cleared much more rapidly in tissues compared with IgA, and thus many DIF-negative vasculitides likely represent IgM/IgG-positive vasculitides.

If the history, clinical examination, and diagnostic tests reveal evidence of other affected organ systems, the diagnostic workup, including the performance of imaging procedures, must be extended accordingly.

Findings suggestive of the presence of systemic vasculitis include extensive skin manifestations (spread of purpura above the waistline, hemorrhagic and necrotic skin lesions, livedo racemosa), reduced general health, detection of IgA in direct immunofluorescence, or laboratory detection of ANCA.

Therapy management

After exclusion of important vasculitis mimics, first and foremost exclusion of bacteremia/sepsis, the identification and elimination of vasculitis-causing factors or treatment of the underlying disease is the first and most important therapeutic step.

Because of the frequently favorable spontaneous course, a wait-and-see approach is warranted in uncomplicated cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis. Symptomatic treatment with compression therapy, physical rest, elevation of the legs and, if necessary, local therapy with topical corticosteroids can promote further spread of the skin lesions and their healing. The vast majority of these vasculitides heal within weeks to a few months, but recurrences are possible.

The temporary use of systemic corticosteroids is justified in cutaneous vasculitis, especially when the development of necrosis and ulcer-tio-nes on the skin is evident via blistering. Treatment with systemic corticosteroids should be reduced and discontinued after a few weeks, if possible. The local therapy of necroses and ulcerations is based on the principles of modern wound management including debridement and moist wound treatment. Of course, attention must also be paid to adequate pain management. In poorly healing vasculitic ulcers, it is often not the vasculitis itself that is the underlying cause, but a coexisting chronic venous insufficiency or arterial occlusive disease that needs to be treated.

If new skin lesions occur after steroid reduction or if the course of cutaneous vasculitis is chronically recurrent, the use of dapsone or colchicine can be considered as a first step and methotrexate, azathioprine, or ciclosporin as a steroid-sparing alternative as a second step.

In the presence of systemic vasculitis, interdisciplinary therapy management is recommended. The benefits and side effects of therapy must be weighed individually. In severe cases, treatments with high-dose systemic steroids and, secondarily, cyclophosphamide are the mainstay. Other therapeutic options include TNF-alpha blockers, rituximab, intravenous immunoglobulins, or plasmapheresis, depending on the type and severity of the vasculitis.

Take-Home Messages

- Different classification systems and sometimes inconsistently used nomenclatures complicate the overview.

- Immune complex vasculitis is the most common form of vasculitis. It usually remains confined to the skin.

- Immune complex vasculitis is characterized by palpable, nonretractable purpura beginning on the lower legs and ascending proximally.

- One should always ask in diagnosis and therapy whether it is an isolated cutaneous vasculitis or a systemic vasculitis with cutaneous involvement.

- After exclusion of important vasculitis mimics, identification and elimination of vasculitis-causing factors or treatment of the underlying disease represents the first and most important therapeutic step.

Further reading:

- Sunderkötter CH, Zelger B, Chen KR, et al: Nomenclature of Cutaneous Vasculitis – Dermatologic Addendum to the 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Convergence Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis & Rheumatology 2018; 70(2): 171-184.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al: 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2013; 65: 1-11.

- Sunderkötter CH, Pappelbaum KI, Ehrchen J: Cutaneous symptoms of vasculitides. Dermatologist 2015; 66: 589-598.

- Kinney MA, Jorizzo JL: Small-vessel vasculitis. Dermatologic Therapy 2012; 25: 148-157.

- Schad K, Kerl K, Dummer R, Cozzio A: Hypersensitivity vasculitis. Switzerland Med Forum 2012; 12(11): 241-246.

- Schäkel K, Meurer M: Cutaneous vasculitides – ways to diagnosis. Dermatologist 2008; 59: 374-381.

- Sunderkötter C, Roth J, Bonsmann G: Leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Dermatologist 2004; 55: 759-785.

- Fiorentino DF: Cutaneous vasculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003; 48(3): 311-340.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2020; 30(6): 15-20