What are risk factors for suicide and how does the physician recognize in time whether his patient is at risk? The concept of the narrative interview is suitable for a trust-building doctor-patient conversation.

In 2015, 1071 people committed suicide in Switzerland, with the rate being three times higher for men than for women [1]. Although this makes suicide the fourth leading cause of death after cancer, cardiovascular disease and accidents, this phenomenon is often underestimated as a health problem. This is problematic not only because of the lethal outcome for the suicide victim, but also with regard to the suffering of affected relatives, friends or indirectly involved persons (e.g. train drivers) [2]. It is therefore all the more important that suicidal persons are recognized and accompanied in their distress.

Notes and risk factors

The greatest risk factor is a previous suicide attempt. Even if this happened a long time ago, the survivor’s risk of trying again is 40-60 times higher compared to the average population [3]. The probability also does not decrease over the years, but increases with each additional attempt [4]. “In the first year, 16% attempt suicide again,” explains Prof. Michel, “and within two years, it’s 25%.” The question of previous suicidal crises is therefore essential and, in the sense of a careful anamnesis, a mandatory component of the doctor-patient discussion. In practice, however, it is too rarely asked, as was shown in a study conducted by the speaker: in half of the suicide cases, the attending physician knew nothing about previous suicide attempts [5].

WHO also cites mental illness such as depression, chronic pain and suffering, substance abuse, a suicidal family history, personal and financial loss, and genetic and biological factors as other individual risk factors. Personal resilience plays a significant role, and comorbidities with other risk factors are common [6].

About what warning signs might the physician infer suicide risk? Indications can be, for example, emotional crises, life crises or depressive symptomatology. A signal may also be that the patient visits his or her physician with an unclear concern that precedes the actual reason for the consultation – help with suicidal ideation; often somatic problems are at the forefront of the consultation first.

The Tower of Babel Syndrome

It can be assumed that suicidal people want to talk about their mental anguish. They want someone who will “just listen.” Yet their suicidal thoughts often go unspoken. Why? One reason lies in the importance of feelings of shame. Interviews with the parents of 33 adolescent suicide victims showed that they suffered from various forms of shame: shame for certain actions, for experiences, their own appearance, or their own person. 89% of the suicide victims hid this shame behind “masks”, which parents and also doctors had not been able to see through [7].

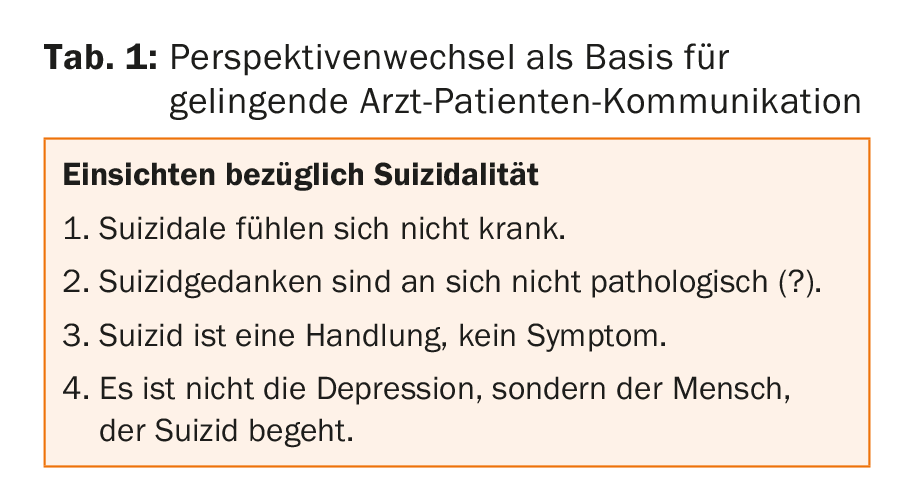

In addition, suicide is something private for those affected, which is experienced and accepted as part of personal development, according to Prof. Michel. “Those affected do not feel that suicidal ideation should be treated by a physician.” This is also how the subordinate role that suicide survivors attested to physicians in a study can be interpreted. When asked who could have helped, 52% of respondents answered “No one,” 20% referred to relatives and friends, and only 10% referred to the physician [8]. Prof. Michel was therefore not uncritical of the usual medical approach, which consists of making a diagnosis and the associated therapy, but is unsuitable for discussions with suicidal people: while the doctor wants to prescribe an antidepressant on the basis of the diagnosis of depression (which is frequent in suicidal cases), the patient thinks about his apparent failure in life and does not understand why he should take medication. Prof. Michel calls this the Tower of Babel syndrome: “They are two different worlds,” doctor and patient do not speak the same language. Four central insights that focus on the individual can facilitate a change of perspective and thus productive doctor-patient communication (Table 1). Suicide must not be “pathologized” so that suicidal patients can turn to their doctors with confidence and without fear of presumed forced admission. It is a matter of “getting beyond the psychiatric diagnosis and finding the person in the patient.”

Talking about suicidality

Timely assessment of whether or to what degree a patient is threatened by suicidal ideation proves challenging in clinical practice. There is no patent remedy. However, conversation is still considered the most effective method of suicide assessment [9]. Prof. Michel illustrated possible approaches to the patient with a role play based on a real case: A patient visits his doctor. He complains of a foot injury sustained while jogging in the woods at night. In the real case, the attending physician did not recognize the acute suicide danger; the patient took his own life a few hours later. So how can the physician inquire about suicidality? One possibility is to use symptoms to break down the psychosocial problem, especially since acute suicidal patients are rarely symptom-free; said patient had sleep disturbances, which is why he went jogging at night. The question “How are you?” is also suitable as an introduction – especially if the patient has not been to the practice for a long time, comes unexpectedly for a check-up or has an unclear concern.

Building on an action theory premise – “We explain actions and plans in terms of stories” – Prof. Michel introduced the concept of the narrative interview. This is also used in the Attempted Suicide Short Intervention Program (ASSIP) recently developed by the University of Bern [10]. The traditional, hierarchical doctor-patient communication with the doctor as the expert is being reshaped. Through the physician’s prompting – e.g., “Please tell me how it got this far” – the patient becomes the expert on his or her story. By keeping the conversation open and asking specific questions, the physician gains insight into the meaning of the suicidal thoughts, specific plans and their preparation, possible suicidal past, etc. Sharing the story establishes the vital “connection to the patient” by building trust. “Asking about suicidal thoughts never triggers suicide,” Prof. Michel concludes. As an attentive listener, it is important to understand the logic behind the crisis – and then to initiate therapeutic measures together with the patient (Tab. 2). Maintaining contact with the patient in the form of follow-up (e-mails, telephone calls, etc.) is equally central to clinical suicide prevention [11].

Source: SGAIM Spring Congress, May 30-June 1, 2018, Basel

Literature:

- FSO: Cause of death statistics 2015. Media Release. 2017. www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/kataloge-datenbanken/grafiken.assetdetail.3742835.html.

- Swiss Health Observatory: Suicide. 2016. www.obsan.admin.ch/de/indikatoren/suizid.

- Runeson BS: Suicide after parasuicide. Evaluate previous parasuicide even if in the remote past. BMJ 2002; 325: 1125.

- Jenkins GR, et al: Suicide rate 22 years after parasuicide: cohort study BMJ 2002; 325: 1155.

- Michel K: Suicides and suicide attempts: could the doctor do more? Schweiz med Wschr 1986; 116: 770-774.

- World Health Organization: suicide prevention: a global challenge. Status 2016.

- Törnblom AW, Werbart A, Rydelius PA: Shame behind the masks: the parents’ perspective on their sons’ suicide. Arch Suicide Res 2013; 17(3): 242-261.

- Michel K, Valach L, Waeber V: Understanding deliberate self-harm: the patients’ views. Crisis 1994; 15(4): 172-178.

- Bryan CJ, Rudd MD: Advances in the assessment of suicide risk. J Clin Psychol 2006; 62(2): 185-200.

- Gysin-Maillart A, et al: A Novel Brief Therapy for Patients Who Attempt Suicide: A 24-months Follow-Up Randomized Controlled Study of the Attempted Suicide Brief Intervention Program (ASSIP). PLoS Med 2016; 13(3): e1001968.

- Zalsman G, et al: Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 2016; 3(7): 646-659.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2018; 16(4) – published 8.6.18 (ahead of print).