A 54-year-old housewife suffered an acute episode of angioedema of the tongue and posterior pharyngeal wall and required emergency treatment in the intensive care unit (Fig. 1). Since the swelling occurred 30 minutes after eating spaghetti with tomato sauce and clams, an allergic event was thought to be present and the patient was referred for an allergological workup. The physician’s report mentioned pre-existing mild pancytopenia.

The allergological history was unproductive with regard to pre-existing atopic conditions; in particular, there was no evidence of previous allergic or intolerance reactions related to the diet. Accordingly, prick tests (atopy screening, food overview, incl. mussels) and IgE determinations were negative. Before the episode, the patient was not taking ASA-containing preparations or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, nor was she on therapy with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin (AT)-II antagonists (sartans) [1, 2].

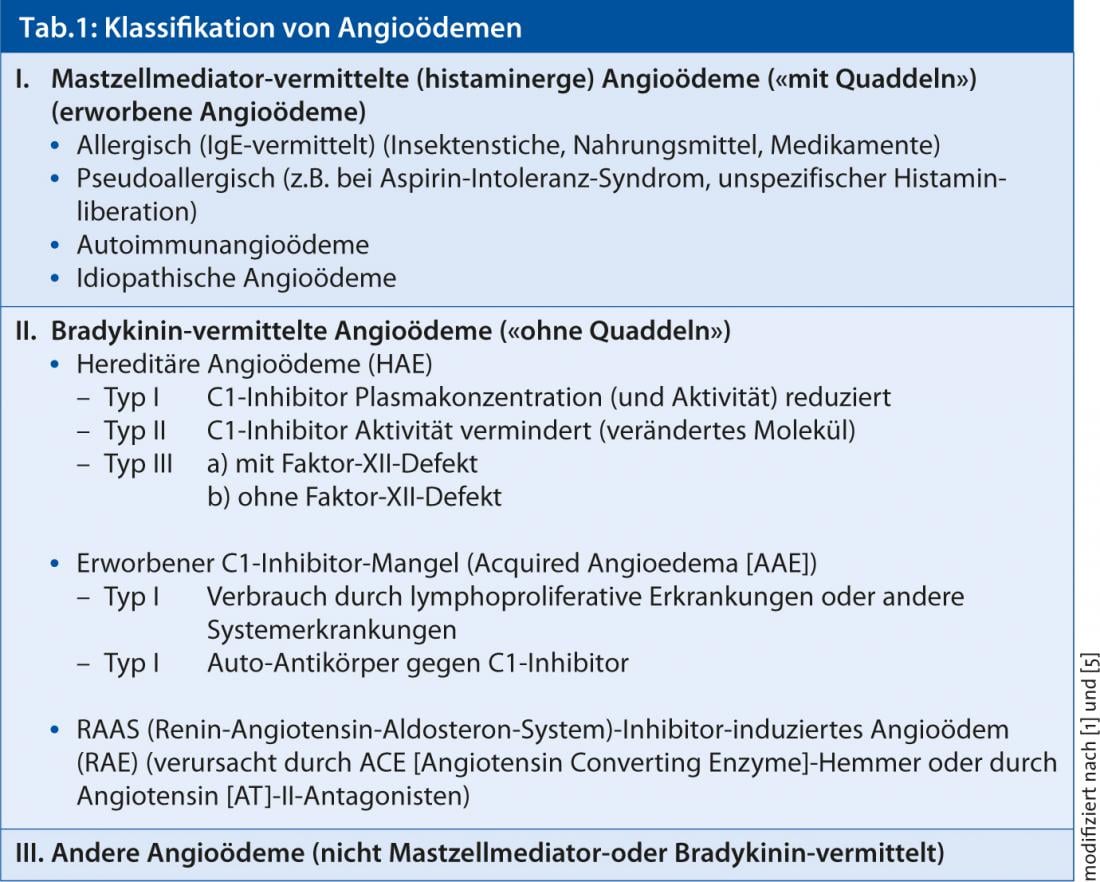

In the differential diagnostic consideration of angioedema (Table 1) , in the absence of anamnestic evidence for triggering factors, the occasional complained abdominal pain was interpreted in connection with the particular localization of the angioedema episode in terms of hereditary angioedema and the complement profile was examined.

Both C1 inhibitor protein (<0.03 g/l; normal range 0.2-0.36) and C4 levels (<0.01 g/l; normal range 0.1-0.4) were not measurable. Similarly, C1 inhibitor function was very low at <18% (norm 70-135%; Immunological Laboratory, USZ).

Under the working diagnosis of hereditary angioedema (type I), therapy with the attenuated androgen danazol (Danatrol), initially 40 mg/die for two weeks, followed by 200 mg/die for an additional two weeks, was initiated for seizure prophylaxis. A check of coagulation parameters revealed the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (anticardiolipin -IgM 520 IU/l; norm <15 IU/l); serology for antinuclear and anti-DNA autoantibodies was negative, ruling out systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The original diagnosis of hereditary angioedema was revised to “acquired angioedema (acquired-angioedema [AAE]) with C1 inhibitor deficiency in association with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS).”

The diagnosis of AAE was subsequently confirmed with the determination of decreased C1q and C1r levels twice (C1q 0.014 g/l; norm: 0.0460-1116 g/l and C1r 37%; norm: 75-125%). Finally, a bone marrow biopsy led to the diagnosis of B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL, IgG κ).

Diagnosis

Acquired angioedema (AAE) in acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency (type I) due to consumption/presence of an inhibitor in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Discussion

Based on the mediators involved, angioedema is now pathogenetically classified into mast cell-mediated or histaminergic (often also accompanied by urticaria) and bradykinin-mediated (not accompanied by wheals) (Table 1) [1, 5]. Among the latter, in addition to hereditary angioedema (HAE) (types II and III) due to C1 inhibitor deficiency and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitor-induced angioedema (RAE) caused by ACE inhibitors or AT-II antagonists, there is another extremely rare form of angioedema, which is also characterized by C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) deficiency [4]. However, the deficiency here is not caused by a change in the genes (hereditary factors), but by certain “acquired” diseases or processes in the body that increasingly consume or inactivate (or inhibit) C1-INH. As a result, too little (functional) C1-INH is available to curb excessive bradykinin formation. Bradykinin levels increase and swelling of the skin and mucous membranes may develop. Unlike hereditary angioedema, this rare form of bradykinin-mediated angioedema usually occurs after age 30 and does not affect other family members. Acquired angioedema can be the concomitant of another underlying disease, which must be clarified by a physician in any case.

In the present case, it was initially crucial to determine the complement factors C4 and C1 inhibitor to exclude histaminergic angioedema, e.g., in case of suspected food allergy. Further determination of the first complement components C1q and C1r served to differentiate between an HAE and an AAE. The underlying disease in AAE needed to be further explored serologically (exclusion of autoimmune diseases, such as SLE and others) and by bone marrow biopsy [6]. The pancytopenia could be explained in the context of bone marrow involvement of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Conclusion

In most cases, angioedema is due to allergic causes. Nevertheless, there are also angioedemas not caused by allergies, which occur comparatively extremely rarely and whose medical background often remains unobserved for a long period of time. Because the different types of angioedema each require different treatment methods, the reason for the swelling must be identified in advance.

Basically, the following forms of angioedema are differentiated:

- Histamine-mediated angioedema (this includes both allergy- and drug-induced angioedema).

- Bradykinin-mediated or hereditary angioedema (HAE) caused by C1 inhibitor deficiency or defect.

This clinical case has demonstrated that C1 inhibitor deficiency can not only be inherited but rarely also acquired, in which case it is referred to as acquired angioedema (AAE). The decisive factor for establishing the diagnosis is the laboratory examination. Performing prick tests and determining C1 and C4 inhibitors allows histaminergic angioedema to be ruled out as a first step. By measuring the levels of the individual blood values C1q and C1r, a distinction can be made between an HAE and AAE in a further step. While the first swelling

attacks in HAE always occur before the age of 30, the rare AAE usually appears after that age. An AAE may be indicative of an underlying primary disease and should not be ignored under any circumstances.

Literature:

- Wüthrich B: Angioedema. Rarely allergic in origin. First part: classification, pathophysiology, diagnostics. Switzerland Med Forum 2012; 12 (7): 138-143.

- Wüthrich B: Angioedema. Rarely allergic in origin. Second part: Therapy. Switzerland Med Forum 2012;12 (8): 175-178.).

- Wüthrich B: Is Quincke’s edema present? Differential diagnosis to angioedema. DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2012; 1: 20.

- Wüthrich B: What is your diagnosis? (Quiz). DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2011;3: 38 and 42.

- Maurer M, Magerl M: JDDG 2010; 8/9: 663-672.

- Beretta KR, et al: Swiss Med Wschr 1991; 121: 943-947.