Burnout is a stress-associated disorder that, when severe, can be considered a disease. It represents a risk condition that can lead to psychiatric and somatic sequelae if stress levels become chronic. In severe burnout, over 50% of those affected exhibit depression, generally major depression. As an expression of the stress-related triggering, it is accompanied by multiple vegetative complaints, a pronounced exhaustion and a significantly reduced resilience with regard to minor stresses. This can be described as a neurasthenic component. If such fatigue depression is present, guideline-based therapy with antidepressant medication is indicated.

Relieving the affected person of the main stress factors and pursuing an active treatment strategy are the first important measures in burnout. Since burnout is the result of various factors, a multimodal approach to therapy is advisable. In addition to psychopharmacological treatment, relaxation measures, sports activation depending on the resilience, careful monitoring of the energy level and body applications prove to be very helpful. Psychotherapy is an indispensable component of treatment. Cognitive-behavioral and multimodal methods have proven particularly effective.

Definition

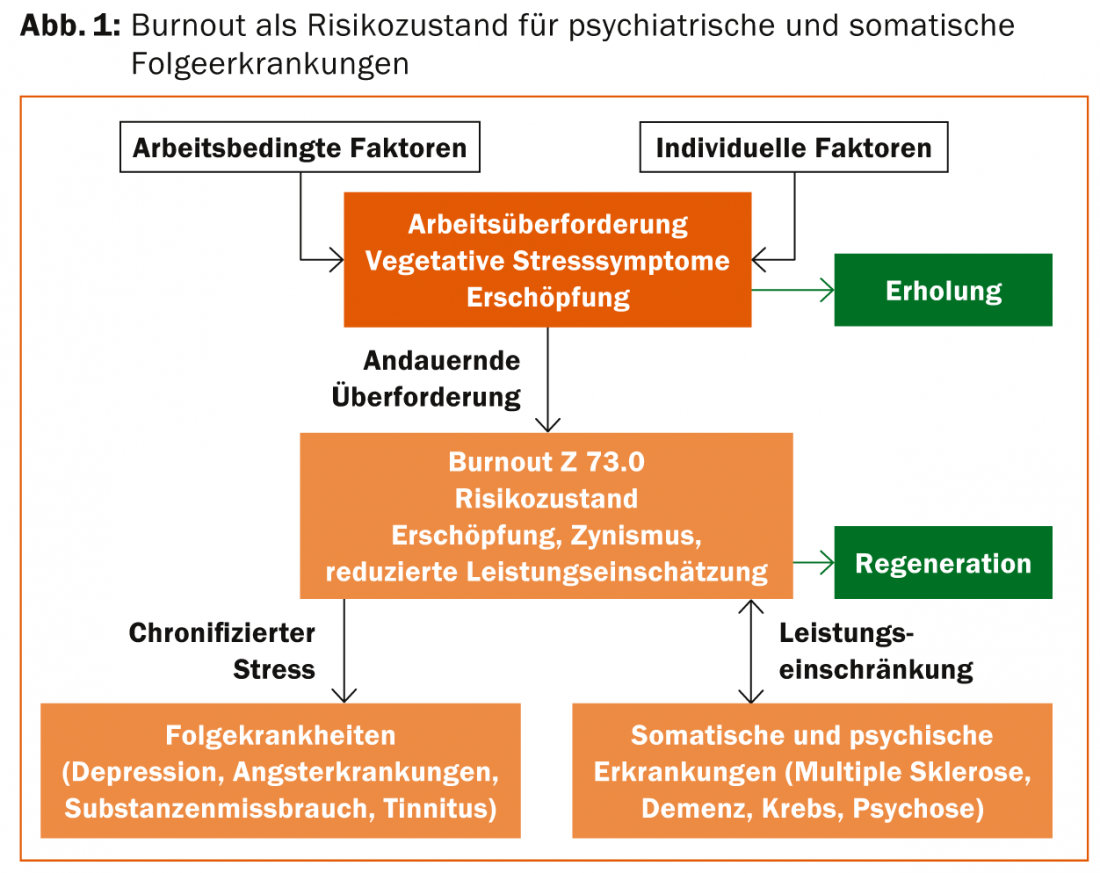

The term burnout originates from organizational psychology and describes a state of exhaustion, linked to demotivation and reduced performance. The term is understood as an expression of prolonged stress, especially in the workplace. There is medical consensus that burnout is not a psychiatric disorder in its own right, but rather a clinical syndrome that can certainly take on disease value. Thus, the ICD-10 defines burnout as “being burned out” under Z73.0, it is “problems related to difficulties in coping with life” [1]. According to the German Society for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Neurology (DGPPN), burnout is a risk condition that leads to psychiatric and somatic sequelae if the stress load becomes chronic [2] (Fig. 1) . Somatically, these are primarily cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndrome, diabetes and obesity [3,4]. Psychiatrically, depression, anxiety disorders, tinnitus, and addiction are prominent.

Burnout is therefore a process that initially presents itself as an expression of an increased stress load, which with ongoing chronification leads to permanent symptoms of dysfunctional stress regulation and increasing exhaustion, followed by a third phase in which multiple vegetative complaints are joined by a significantly reduced resilience in the sense of a neurasthenic component and the clinical features of depression. The question in this third stage is no longer “Burnout or depression?” but rather “Burnout and depression?”

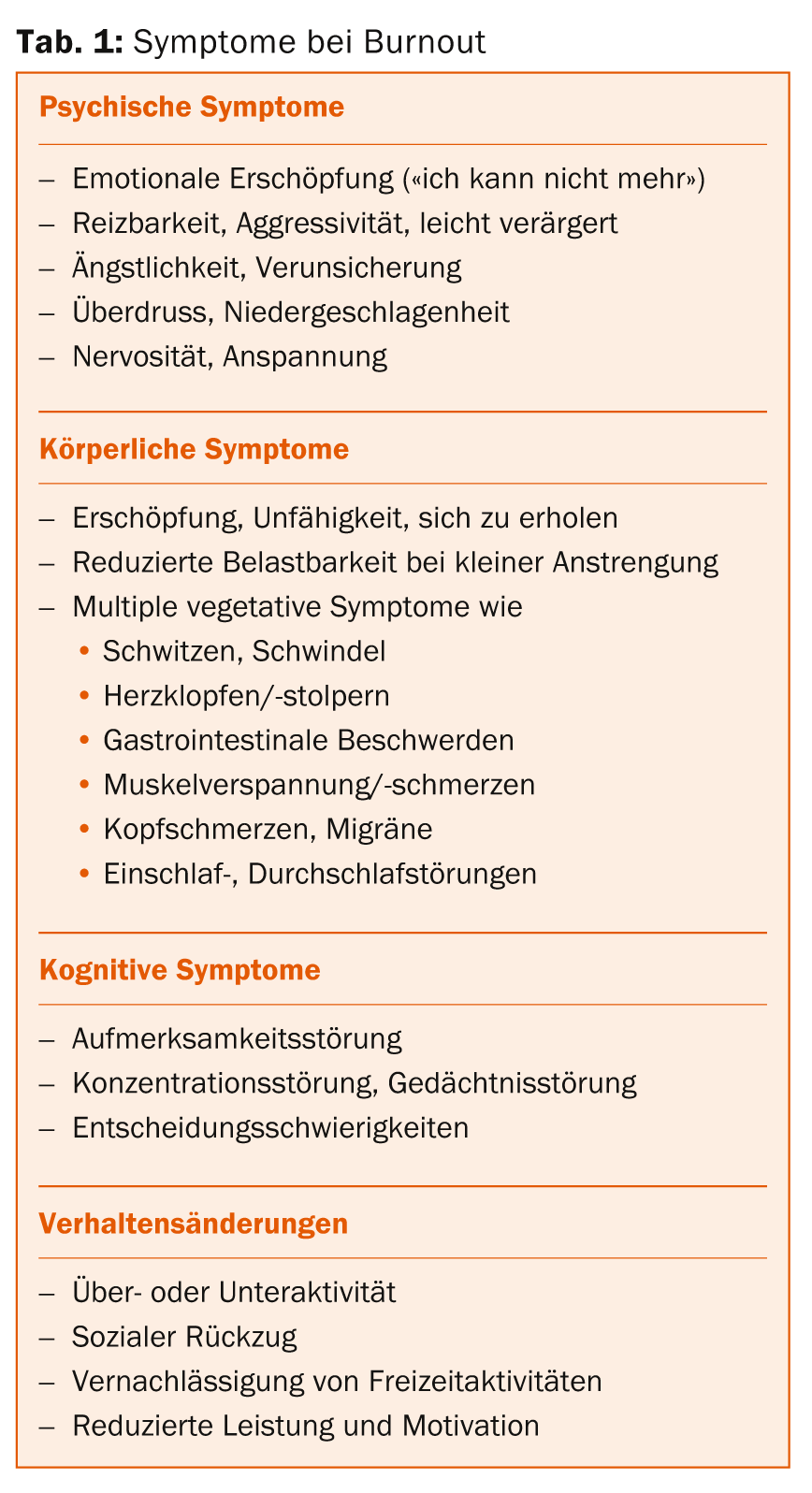

Symptomatology of burnout

The symptoms of burnout are manifold and individually variable. The main symptoms can generally be grouped into four dimensions (tab. 1).

Neurobiologically, burnout can be understood as an expression of allostatic overload, i.e., a regulatory disorder of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis caused by chronic stress [5] and as a failure of central nervous resilience in the presence of region-specific changes in neuronal plasticity factors [6]. In most clinical cases, there is a dysregulation of the HPA system triggered by permanent stress [7], due to an increased production and release of the hormones CRH and AVP secreted by the hypothalamus [8,9]. However, because regulatory disorders take place in central areas of the CNS, peripheral cortisol levels are of little value [10].

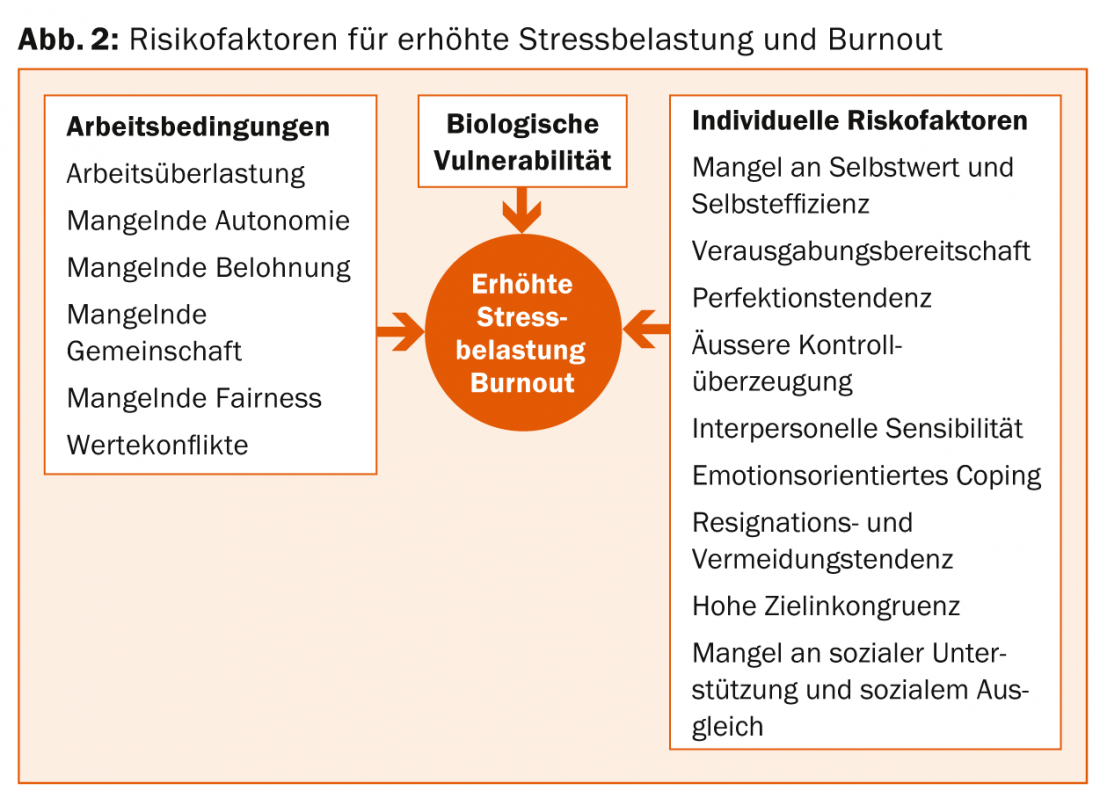

Psychosocially, burnout is seen as an expression of a lack of fit between the individual worker and his or her job. Both organizational and personal factors play a key role here. Leiter and Maslach [11] summarize the organizational risk factors that have been shown to be relevant to burnout development into six areas.

Individual risk factors include, in addition to possible biological vulnerability in terms of increased stress response or depressive development [12], primarily a lack of self-esteem and stress-reinforcing cognitions and behaviors [13–16] (Fig. 2).

Differentiation between burnout and depression

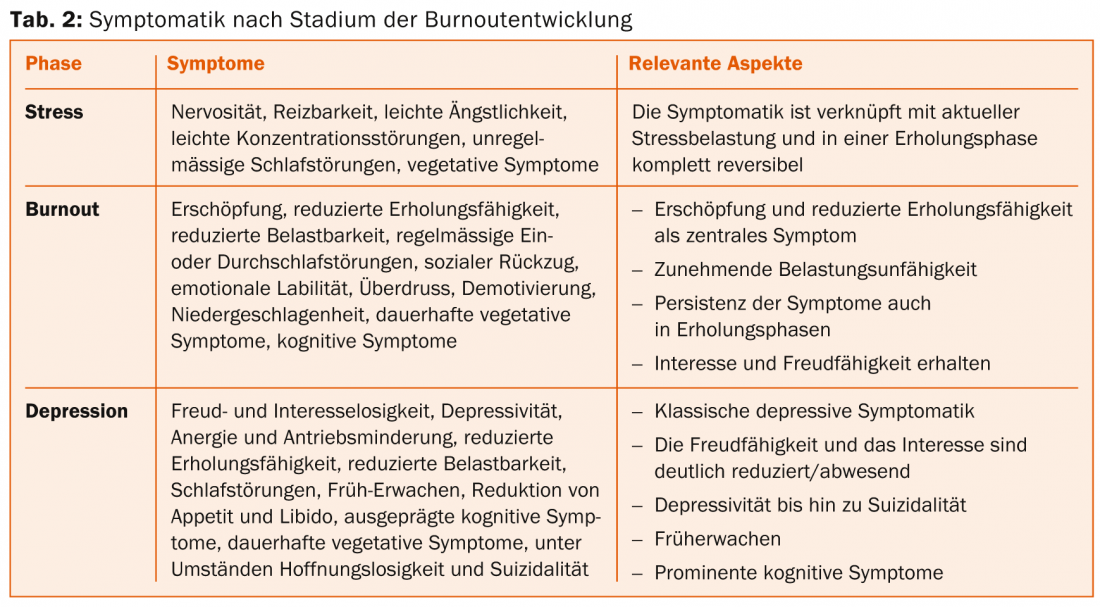

The final stage of a burnout process in most cases is the development of clinical depression. In a representative cross-sectional study of the Finnish working population, over 50% of subjects with severe burnout had concurrent depression [17]. The most common form of depression was major depression, followed by milder forms of depression. Simplified, the development of burnout with the relevant phase-specific symptomatology can be depicted as in table 2.

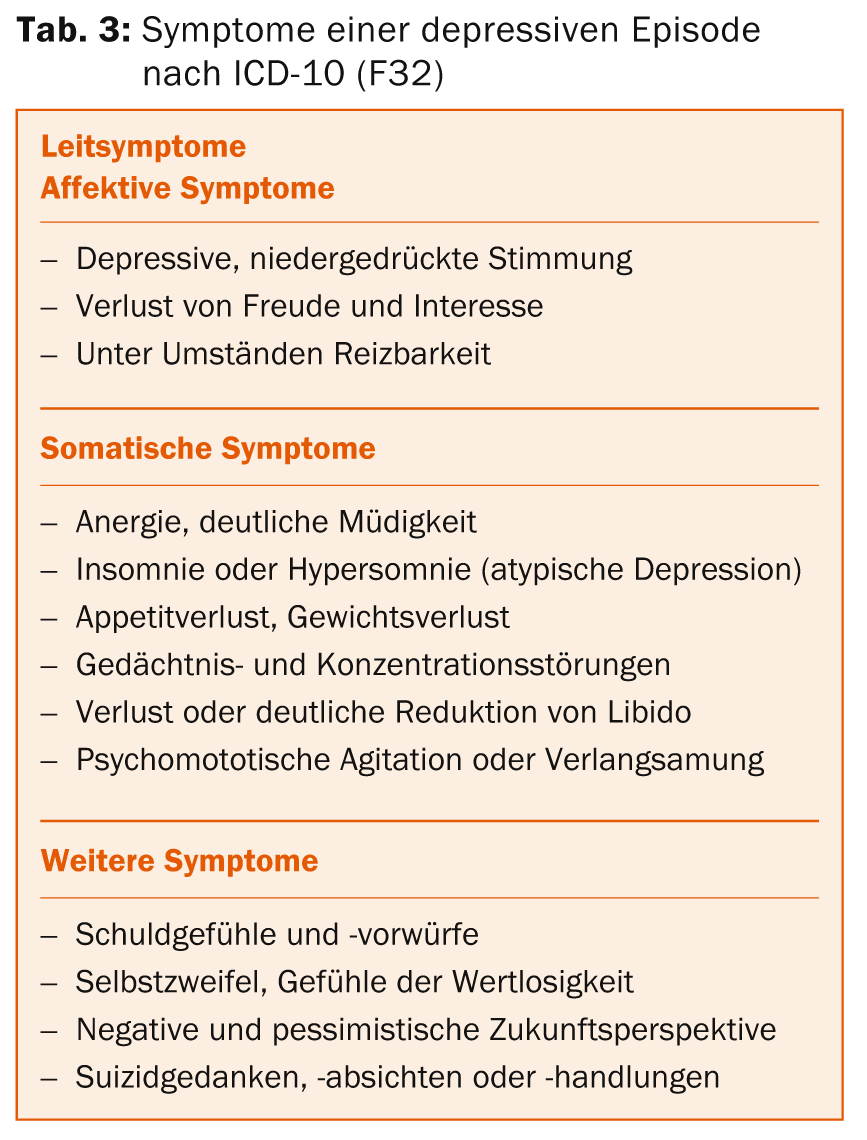

Depression differs from burnout not only in the severity of symptoms, but also in the specific pattern of symptoms typical of depression [1]. This includes the affective component of dejection, lack of interest and pleasure, and occasional irritability, as well as the somatic component with reduction or loss of appetite, libido, energy, drive, ability to concentrate and remember, and ability to sleep. Early awakening without being able to fall asleep again is typical of depression (tab. 3) . These symptoms must have lasted at least two weeks for a diagnosis of depression.

Depression occurring in the context of chronic stress exposure appears to be associated with multiple vegetative symptoms and long persistent reduced resilience, like burnout. A description of this form of depression was already given by Kielholz under the term “exhaustion depression” [18]. Exhaustion as a leading symptom and, as in neurasthenia, persistent exhaustibility with little mental or physical effort are emphasized as integral to this form of depression.

Recommendations for the diagnosis of burnout and/or depression

Diagnosis is based on anamnesis, clinical interview and psychostatus. A thorough differential diagnosis by internal medicine is essential. It is advisable to use supporting questionnaires that depict the respective psychiatric disorders with appropriate reliability and validity. The self-report instrument “Beck Depression Inventory” [19] and the third-party assessment instruments Hamilton Depression Scale [20] and Montgomery-Asberg Depression Scale [21] are suitable for assessing depressiveness or depression. The Shirom-Melamed Burnout Measure [22] and the Maslach Burnout Inventory [23] are suitable for assessing the severity of burnout.

In the anamnesis it is important to record the triggering stress factors and to sound out the development process of the symptoms in a differentiated way. It is advisable to ask systematically in the clinical interview for classic symptoms in burnout (Tab. 1) and classic symptoms in depression (Tab. 3). In the psychostatus, special attention must be paid to the affective state, drive, energy state, psychomotor activity and thinking.

It is essential to question the patient in detail about the use of substances, especially alcohol, stimulants, sedatives or painkillers, and nicotine, which can distort the clinical picture and delay the course. A secondary addiction may well develop that requires separate therapeutic attention.

Therapy strategies

Since burnout is the result of several different trigger factors, therapy must also take place on several levels [24]. The first thing to do is to relieve the patient of the main stress factors and motivate him to take an active part in therapy and to adapt his activities to his resilience. Simply taking time off is not a sufficient therapy strategy. If clinical depression is present, it is essential to treat it with medication lege artis and in accordance with guidelines [25]. It is advisable to seek a specialist psychiatric evaluation early on.

According to the stress-related genesis of the disorder, relaxation exercises and sports adapted to the performance capacity are recommended to normalize stress regulation. Body therapy and massage not only promote relaxation by stimulating the release of oxytoxins [26], but also improve the usually disturbed body perception of those affected. It is precisely the ability to perceive body signals and limits and to take them into account with regard to one’s own behavior that is a decisive factor for sustainable treatment success. The patient must be instructed to observe his subjective energy level, also as a function of his activities, and to demand himself accordingly only within the limits of the determined resilience. Resuming or increasing work activity should always be done with careful consideration of resilience.

The central component of therapy for exhaustion depression or burnout is psychotherapy. It serves to process the disease process, to work through the stress-triggering factors and to reflect on and correct dsyfunctional cognitions and behaviors, as well as to build up resources for improved stress management and life balance. Due consideration must be given to the work context. Often, it is also necessary to resolve interpersonal conflicts and to shed light on the question of values and goals for the future orientation of life. To date, data are available on cognitive-behavioral therapy approaches, on multimodal strategies, and to a lesser extent on psychodrama and depth psychological group therapy, which have been shown to be effective (albeit with respect to different parameters and with varying effect sizes) [27–30]. Referral to a psychotherapeutically qualified specialist is advisable for a more in-depth therapeutic discussion.

Barbara Hochstrasser, MD

Literature:

- WHO: International Classification of Mental Disorders, Chapter V (F), 1993.

- DGPPN, PuND: Position paper on burnout. 07.03.2012.

- Shirom A, et al: Burnout and Health Review: Current Knowledge and future Research Directions, In: Int Rev Ind Organ Psycho 2005; 20: 261-288.

- Melamed S, et al: Behav Med 1992; 18: 53-60.

- McEwen B: NEJM 1998; 338(3): 171-179.

- Krishnan V, Nester E: Nature 2008; 485: 894-902.

- Menke A, et al: Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014; 44: 35-46.

- Griebel G, Holsboer F: Nat Rev Drug Discov 2012; 11(6): 462-478.

- Holsboer F, Ising M: Annu Rev Psychol 2010; 61: 81-109.

- Mommersteeg P, et al: PNEC 31 2006; 798-804.

- Head MP, Maslach C: JHHSA 1999; 472-489.

- Nyklicek I, Pop VJ: J Affec Disord 2005; 88: 63-68.

- Haberthür A, et al: J Clin Psychol 2009; 65(10): 1-17.

- Lehr D, Schmitz E, Hillert A: Z for Organizational Psychology 2008; 52: 3-16.

- Schaarschmidt U, Fischer A: Work-related patterns of behavior and experience. 1996.

- Schramm E, Berger M: The Neurologist 2013; 84(7): 791-798.

- Ahola K, et al: J Affec Disord 2005; 88: 55-62.

- Kielholz P: Schweiz Med Wochenschrift 1957; 5: 107-110.

- Hautzinger M, et al: Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), test manual. 1995.

- Hamilton M: The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, In: Assessment-of-Depression. 1986; 143-165.

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M: Brit J Psychiat 1979; 134: 382-389.

- Shirom A, Ezrachi Y: Anxiety, Stress and Coping 2003; 16(1): 88-97.

- Schaufeli WB, et al: In: MBI Manual. 1996.

- Hochstrasser B, Keck ME: Therapy recommendations of the Swiss Expert Network Burnout (SEB) for the treatment of burnout. In preparation.

- Holsboer-Trachsler E, et al: Swiss Medical Forum 2010; 10: 802-809.

- Kanat M, et al: Brain Res 2013. [Epub ahead of print].

- Elkuch F, et al: Behavior Therapy & Behavioral Medicine 2010; 31(1): 4-18.

- Näätänen P, Salmela-Aro K: Int J Behav Dev 2006; 30(6 suppl): 10-13.

- Van der Klink J, et al: Am J Public Health 2001; 91: 270-276.

- Van Rhenen W, et al: Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2005; 78: 139-148.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2014; 12(6): 24-27.