Is dying at home a utopia and an almost unsolvable task for the family doctor or quite feasible? This question was explored in a workshop at the SwissFamilyDocs conference. For Hansruedi Banderet, MD, the most important goal in the treatment of dying patients is anticipatory care planning.

Hansruedi Banderet, M.D., Basel, presented the somatic medical history of Mr. B.F., a 77-year-old patient in the terminal phase who showed agitation, local and temporal disorientation, anxiety, and, in the last weeks of life, delirium in the clinic. The so-called Advance Care Planning, a comprehensive plan to improve end-of-life care, specified the patient’s home as the place of care and death, but no invasive therapy or cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). The support came from the family, primarily from the wife and partly from the neighbor. (Onco-)Spitex was desired, if necessary. The procedure in emergencies should be sensibly anticipated via reserve medication, documentation with the patient and announcement of the appropriate cell phone number.

Findings from a national interview study with 25 primary care physicians indicate that it is important to negotiate such planning together with the patient and family members (Table 1). This allows the primary care physician to engage in a network of relationships. Good care is only possible in a team and is perceived as relieving by the family doctors. You save yourself a lot of trouble if emergencies are anticipated and patient wishes and special needs are properly documented.

Care beyond death

However, care usually does not end with the patient’s death: Many physicians recommend a debriefing with the relatives; often feelings of guilt need to be put into perspective and uncertainties clarified. “In addition, it should be said that end-of-life care always means preparing for one’s own death,” Dr. Banderet said.

Delir

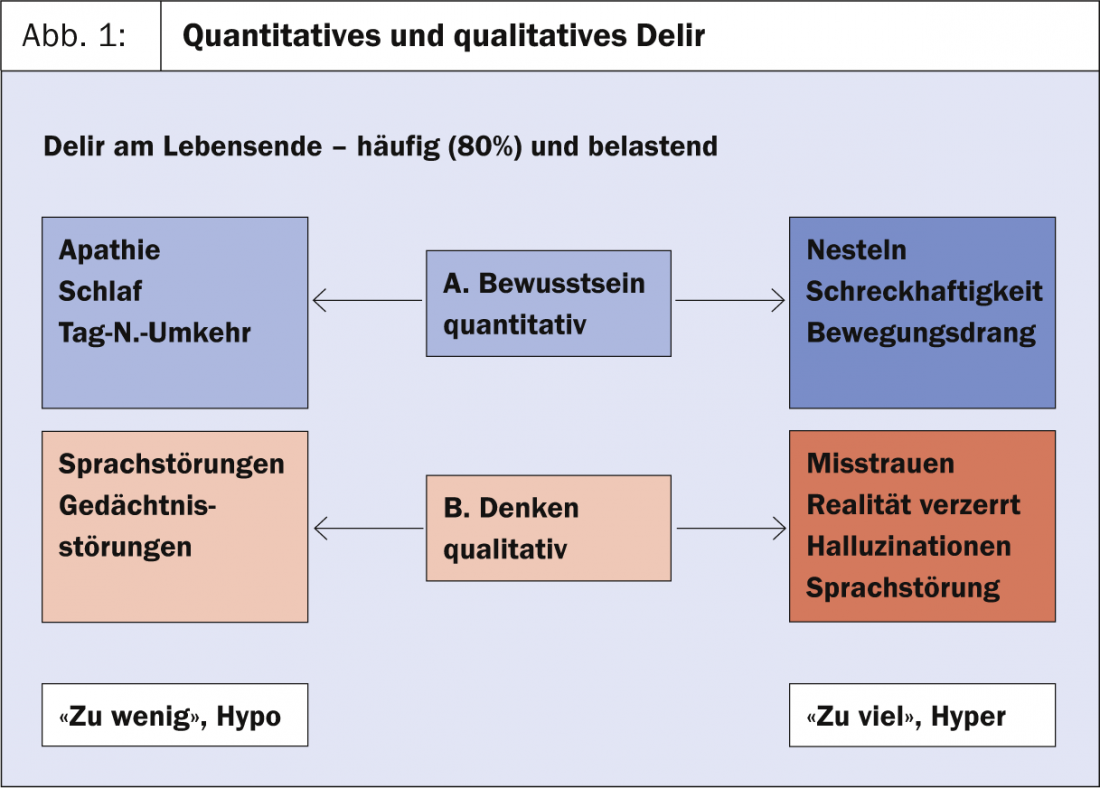

Dr. med. Heike Gudat-Keller, Arlesheim, spoke about delirium and sedation. Delirium at the end of life is frequent and distressing, and is usually multifactorial (Fig. 1). It can be triggered by a tumor (brain metastases, paraneoplastic), medications (such as opioids, steroids, NSAIDs, antiemetics), or an infection (organ failure, electrolyte, BG disturbance). “The main rules are:

- Aim for prevention

- Perform monitoring

- Address treatable causes (reduce medications, opioid rotation, hydration).

- Make clear team arrangements (set time limit)

- Don’t forget information/care for relatives,” Dr. Gudat-Keller said.

Qualitative disorders can be treated medicinally with neuroleptics. Here the first choice is Haldol®, second choices are Nozinan®, Seroquel®, Risperdal®, which are somewhat weaker than Haldol and therefore insufficient for treatment in severe progressive states.

Benzodiazepines help against motor restlessness. The drug of first choice is Valium®, followed by Dormicum® as well as Tranxilium®, and in geriatric patients Dipiperon® (up to 120 mg).

Pallative sedation

“Pallative sedation is the deliberate and monitored administration of sleep-inducing medications, temporary or permanent, weak or strong, at the minimally effective dose for one or more refractory conditions in people with limited life expectancy,” Dr. Gudat-Keller said, summarizing the term. “Relatives often think: sedation is the “shot,” so euthanasia.

As a practitioner, you must have an answer ready. With active euthanasia, the goal is for the patient to die. With sedation, the goal is for the patient to endure the situation. The difference in goal is what matters. Sedation per se does not shorten or prolong life; the term basically only means that the patient is in a dozing or sleeping state. Life-limiting measures are only adjunctive measures such as hydration, nutrition, etc.” For treatment, according to Dr. Gudat-Keller, Dormicum is® (60-200 mg/d) is preferable because you often can’t get the depth of sedation right with other medications. The advantage here is also the short half-life. It can be quickly readjusted if the first dose is not right.

Are primary care physicians competent in palliative care?

This question was posed by Klaus Bally, MD, Basel: “On the one hand, patients seem to appreciate the availability, time and willingness to listen of family physicians. However, they often feel insecure in the field of palliative care. In addition, grieving relatives sometimes have the impression that the treatment in family doctors’ practices is worse than in other institutions. Overall, too little attention is paid to the needs of caregivers, especially family caregivers.”

In any case, he said, it is recommended to proactively approach the patient once they have been identified as a palliative patient. This can be done, for example, with the questions “Where do you think you are in your illness?”, “What should we do if it is no longer possible at home?”, “What does your family say? Should we talk to each other?” or “Do you want to make a precautionary registration in a nursing home/hospice?” concluded Dr. Bally.

Source: “Dying at home – wish or reality?”, Workshop at the SwissFamilyDocs Congress, August 29-30, 2013, Bern.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2013; 8 (10): 39-40