Muscles play a very important role in the whole organism with 40-50% of the total body weight and their (besides mechanical) somewhat less known metabolic functions. In sports, probably with the exception of chess, the musculature has a great importance as a driver and motor of all the maximum movements indispensable for these activities. What happens when we injure our muscles?

Injuries to these structures, which are so important not only in sports, are surprisingly discussed relatively little and infrequently, perhaps because by and large they have a good prognosis due to a strong self-healing tendency. Frequency data varies by author, country, and sport. In athletics, muscle injuries account for almost half of all injuries (48%), while in professional football the figure is still 30%. In Switzerland, SSUV statistics show an incidence of 10% for all sports, including those with a low tendency to injury.

By muscle injuries we mean mainly:

- Muscle bruises

- Muscle tears (strains)

- And perhaps somewhat surprisingly: muscle soreness, scientifically called DOMS (“delayed onset muscle soreness”).

Muscle soreness

There is hardly any other phenomenon from the field of sports activities that raises as many questions as muscle soreness. Why do the muscles hurt mainly after going downhill, but not after going uphill? And what can you do with “hungover” legs? Sore muscles” refers to pain that occurs in stressed muscle groups 12-24 hours after unaccustomed physical exertion, usually during so-called eccentric muscle work. This pain is not related to the accumulation of lactic acid, as is often claimed, but is the result of minute micro-muscle tears that can be seen under an electron microscope. Most often, this muscle pain begins a day after the effort, because the mentioned microtears cause repair processes as the body’s own reactions, which manifest themselves with a delay. These subtle changes in the muscle, which are absolutely benign and also heal without any complication, are often accompanied by a slight feeling of tension and possibly even a slight swelling.

It’s not just running downhill that produces sore muscles. All sports that involve eccentric muscle work – a lot of “stop and go”, i.e. rapid stopping, change of direction and re-acceleration – can trigger muscle soreness. The extent to which the body has become accustomed to the sport also plays a role. This is because unaccustomed forms of exertion are much more likely to cause muscle soreness than those that you exercise regularly.

How to prevent, what remedies?

A careful training program of the muscle groups at risk with strengthening and stretching exercises and additional coordinative work between the different muscle groups is the best prevention. In terms of therapy, if needed at all, sore muscles are best countered with light physical activity. Massage is also often mentioned as a measure. It is by no means harmful, but observation shows that muscle function, as measured by range of motion and muscle strength, recovers at the same rate with or without massage.

As more and more older people practice sports, it is useful to know that the symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica are very similar to those of muscle soreness, only they do not disappear as quickly!

Muscle tears and bruises

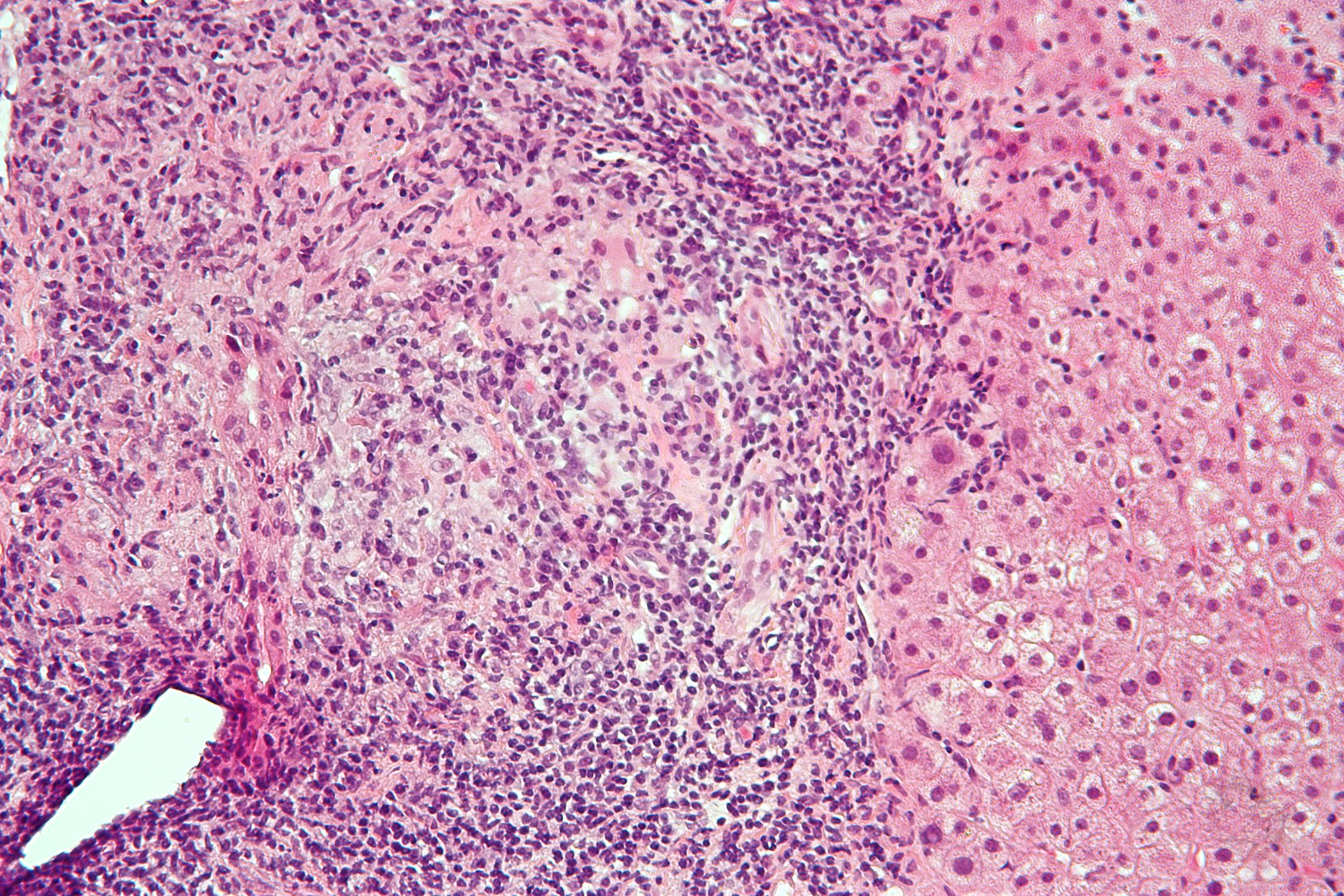

Despite their different origins, muscle contusions and tears in sports are very similar. Due to the contusion of the tissue during contusion and due to the tearing of the muscle fibers because of disproportionate tension – mostly eccentric – tissue damage (muscle fiber damage) and bleeding of the already highly vascularized muscle tissue occur in both situations. These two phenomena are responsible, on the one hand, for the symptoms, mainly pain and functional “impotence”, and, on the other hand, for triggering the classical endogenous repair processes (inflammation with destruction of the damaged tissue, proliferation with tissue repair, and finally remodeling phase).

In the clinical context, the hematoma takes on a particularly important role. The blood mass may be intramuscular (within the fascia) or intermuscular (between the fascia). While the pathologic mass can move in the second case and thus be cleared better, this is not true of intramuscular hemorrhage, which is often more disruptive and associated with worse outcome. The immediate measures on the sports field are also similar for both types of injuries: the well-known but unfortunately underused PECH rule (rest/ice/compression and elevation). Especially P and E are important and easy to perform.

Diagnostics

For the physician consulted, the procedure is classic: the anamnesis clearly points the way, and the athlete usually knows how to describe the situation clearly. Examination sometimes reveals contusion marks, denting depending on the time of examination, measurable limb circumference differences depending on location, hematoma marks, usually distal to the lesion, and almost always localized pressure dolenia. Muscle testing, the functional testing of the affected muscle and the joints it moves, is another investigative step. Femoral contusions in the quadriceps region may result in significant reduction in knee flexion (if this does not reach 90°, an intramuscular hematoma is likely present).

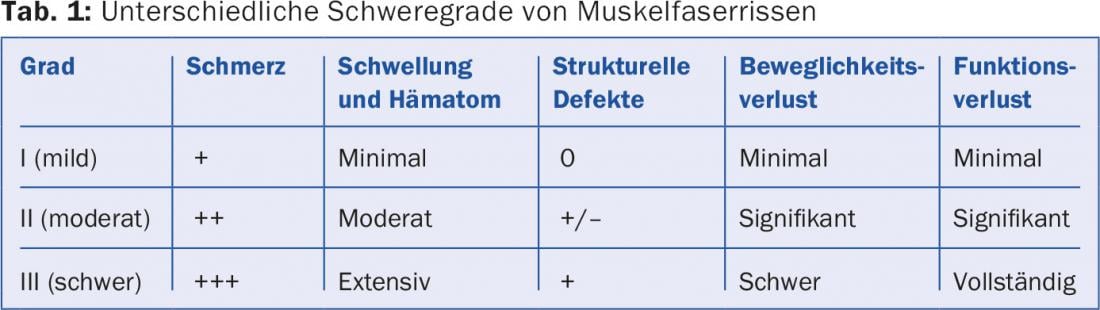

Further clinical clarification depends on the individual case. Radiographs are unnecessary unless there is a suspicion of attachment fracture, e.g. in adolescents. The technique most commonly used today to objectify a muscle lesion is sonography. But MRI examination, more expensive but more accurate, is also recommended by some study groups. In the various classification attempts, especially of muscle tears, there are even those that incorporate MRI results (Table 1).

How to treat?

In the vast majority of cases, therapy is conservative and physiotherapy plays a central role. It can start immediately, will be rather passive initially with increasing activation over time. The use of NSAID is classical, but based more on experience than on scientific facts. Injections of homeopathic or biological substances directly into the injury area have become fashionable among certain sports physicians, and autologous blood preparations are also used (“platelet rich plasma” or “autologous conditioned serum”). Surgery is no longer ruled out for sure, as taught in the past (“muscle cousu = muscle foutu”), but it is used rather rarely.

Forecast

The prognosis of muscle injuries is generally good. However, it depends on the severity of the injury (intramuscular hematoma worse than intermuscular), the immediate measures (mostly independent of the physician), the quality of rehabilitation, the physician’s guidance and the patience of the usually “impatient” patient. It should be clear to all involved that while a muscle injury will show rapid progress, functionally it will take several weeks (up to twelve in severe cases) to restore the tissue to its original capabilities. In this context, it should be noted that the risk of recurrence is relatively high. In the search for contributing factors to muscle fiber tears, it has been found that a major factor is previous injury that has not fully healed.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(8): 4-5