In patients with WPW syndrome, orthodromic AV reentry tachycardia (regular narrow complex tachycardia) is most common, but antidromic AV reentry tachycardia (regular wide complex tachycardia) or atrial fibrillation with conduction across the pathway (irregular wide complex tachycardia) may rarely occur. The acute therapy of choice in patients with WPW syndrome and persistent symptomatic orthodromic AV reentry tachycardia (regular narrow complex tachycardia) is the performance of vagal maneuvers and, if they fail, parenteral administration of adenosine. The acute therapy of choice in patients with WPW syndrome and atrial fibrillation (irregular wide-complex tachycardia) in a hemodynamically unstable situation is electrocardioversion.

Definition of WPW syndrome

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (WPW) is a cardiologic condition defined by the combination of 1) Presence of an antegrade conducting accessory pathway with resulting preexcitation on resting ECG, as well as. 2) the occurrence of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. The prevalence of WPW syndrome in the general population is approximately 0.1-0.3% [1,2]. In addition to the occurrence of reentry tachycardia, atrial fibrillation (VHF) with very rapid conduction to the ventricle may rarely occur. In the worst case, this can lead to ventricular fibrillation and subsequently to sudden cardiac death. The risk of this in patients with WPW syndrome is in the range of 0.25% per year or 3-4% per lifetime [3].

Pathophysiology of the WPW syndrome

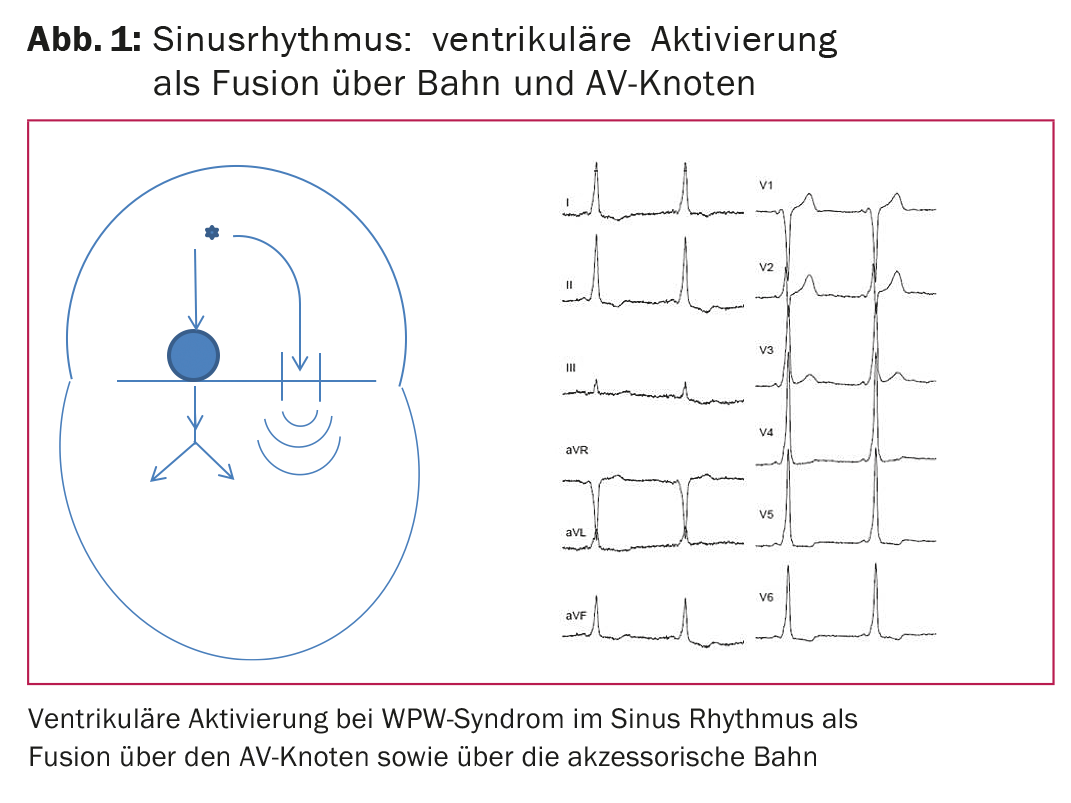

In the electrical conduction system of the heart, the AV node normally represents the only electrical connection between the atria and the ventricles. The anatomic substrate of WPW syndrome is an accessory muscular atrio-ventricular connection outside the AV node (Fig. 1). This connection is called an accessory pathway. In contrast to the AV node, which transmits atrial excitation to the ventricles after a pause, accessory pathways transmit excitation from the atrium directly to the ventricles without relevant delay.

In sinus rhythm, therefore, there is early excitation of the ventricular myocardium in the region of the orifice of the accessory pathway (Fig. 1, schematic). This so-called preexcitation is characterized in the ECG of patients with WPW syndrome by a shortening of the PQ time, the presence of an initial delta wave and thus a broadening of the QRS complex (Fig. 1, ECG). This is a fusion activation of the ventricle, as one part is activated via the accessory pathway and one part is activated via the AV node and the normal conduction system.

Anatomically, accessory pathways can occur anywhere in the tricuspid or mitral annulus. Left-sided tracts are most common, with localization at the lateral mitral annulus. In 10% of all cases, multiple accessory pathways are present simultaneously [4]. WPW syndrome may be associated with congenital heart defects, such as Ebstein anomaly, with multiple accessory pathways present in up to one-third of cases [5].

Rhythm disturbances in WPW syndrome

Three distinct groups of arrhythmias may occur in patients with WPW syndrome: orthodromic AV reentry tachycardia (85%), antidromic AV reentry tachycardia (10%), and atrial fibrillation with antegrade conduction to the ventricles (5%).

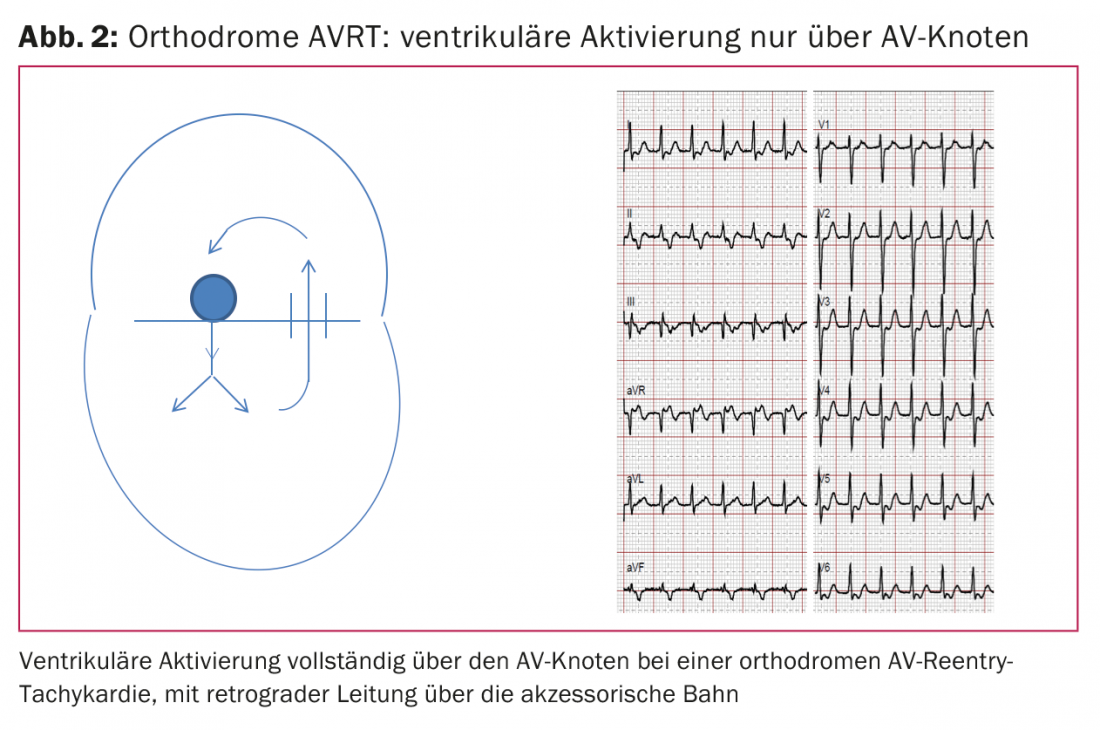

Orthodromic AV re-entrant tachycardia: Orthodromic AV reentry tachycardia is a paroxysmal regular narrow complex tachycardia with rates between 150-250/min. Excitation is conducted from the atrium antegrade to the ventricle via the AV node, using the normal His-Purkinje system to activate the ventricles, which is why the QRS complex is narrow (no delta wave present). The accessory pathway then retrogradely returns excitation from the ventricle to the atrium (Fig. 2).

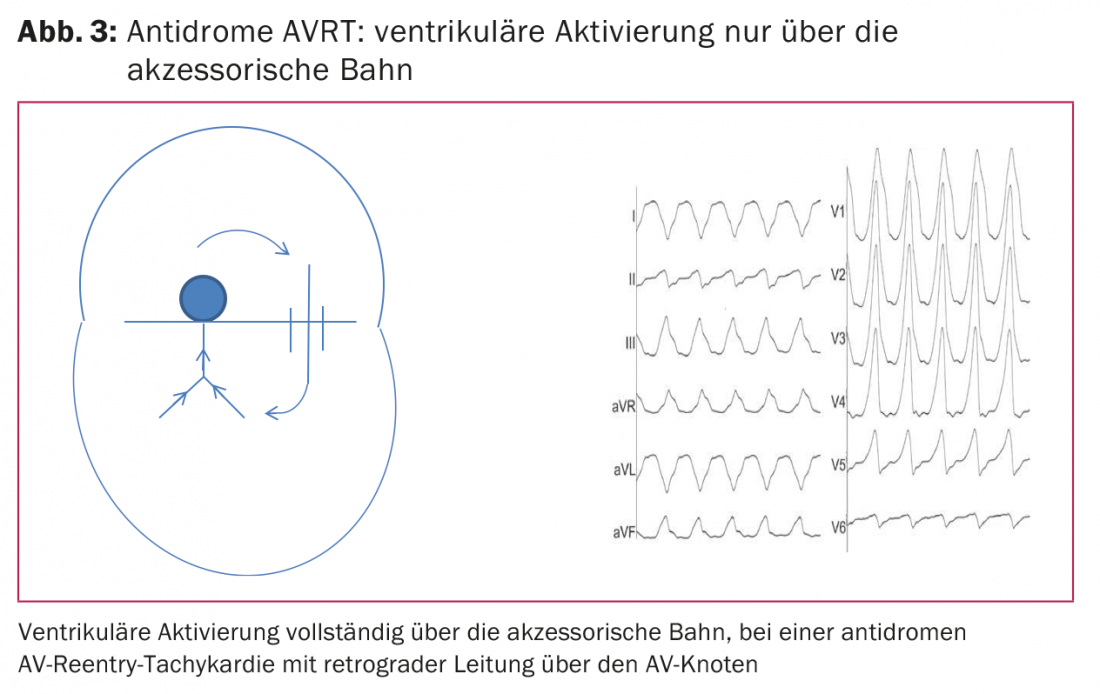

Antidromic AV reentry tachycardia: The much rarer antidromic AV reentry tachycardia is a paroxysmal regular wide-complex tachycardia. Here, excitation is transferred from the atrium antegrade to the ventricles via the accessory pathway. The excitation is transmitted via the working myocardium, which is why the QRS complex is wide. Retrograde conduction back to the atria then occurs via the AV node (Fig. 3).

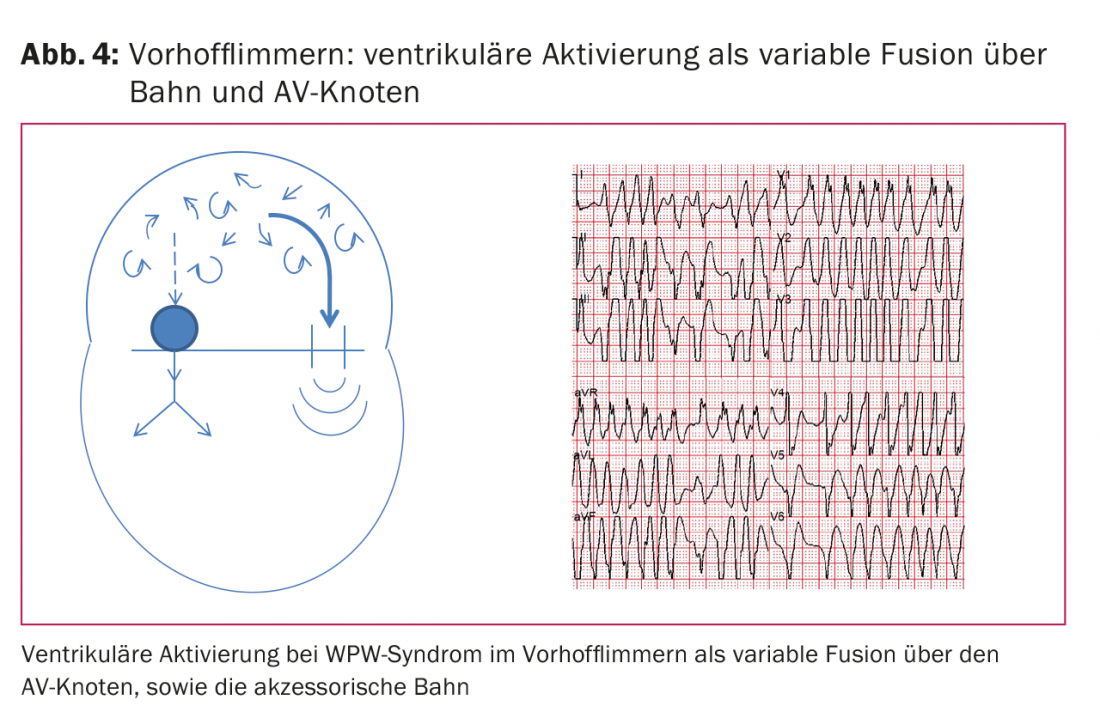

Atrial fibrillation: Atrial fibrillation can occur as a third form in patients with WPW syndrome, which can also occur in young patients with WPW syndrome in 15-40% [6]. This is transmitted antegrade to the ventricles via the accessory pathway and results in widened QRS complexes. These can vary widely from beat to beat because different amounts of myocardium are activated via accessory pathways or AV nodes. In the case of a short refractory period of the accessory pathway (typically less than 250 ms), atrial fibrillation can trigger very fast ventricular rates. The resulting typical ECG is often described as “Fast-Broad-Irregular”, or “FBI ECG” for short (Fig. 4) . In the worst case, 1:1 conduction can lead to ventricular fibrillation with resulting sudden cardiac death.

Diagnostics in WPW syndrome

Basic diagnostics should include history, physical examination, and a 12-lead sinus rhythm ECG to document preexcitation. ECG documentation during a tachycardia episode by 12-lead ECG or long-term ECG should also be sought. In addition, echocardiography should be performed once in all patients with WPW syndrome to exclude structural cardiopathies, especially congenital anomalies.

Studies of noninvasive risk stratification have been performed in the past but have become much less important with the introduction of ablation therapy. On the one hand, an exercise ECG can be performed. Sudden loss of preexcitation at even mildly elevated heart rates during exercise generally implies a long refractory period of the accessory pathway and thus a low risk of sudden cardiac death. Also a low-risk indicator appears to be preexcitation that is only intermittent. Finally, ECG during AF can be used for risk stratification: very fast frequencies in AF with minimal RR intervals below 250 ms imply a very short pathway refractory period and accordingly have a higher risk of sudden cardiac death [1,7].

Therapy for WPW syndrome

Since the 1990s, catheter ablation with radiofrequency energy has been available as a curative treatment for WPW syndrome [8]. During an electrophysiological examination with minimally invasive vascular access via the groin, the position of the accessory pathway is first carefully localized and subsequently ablated. The success rate for permanent elimination of the pathway is over 95%, which also elimates the risk of sudden cardiac death. In young patients with WPW syndrome and concomitant presence of paroxysmal AF, the latter also usually does not recur after pathway ablation [9]. The risks of ablation treatment are <1% for relevant complications, and these are cardiac tamponade or else iatrogenic complete AV block with anteroseptal localization of the pathway near the His bundle.

Persistent symptomatic AVRT: Acute therapy in patients with persistent symptomatic AVRT consists of vagal maneuvers and, in the absence of conversion to sinus rhythm, parenteral administration of adenosine leading to termination of AVRT by a transient AV block.

Atrial fibrillation and WPW syndrome: In patients with atrial fibrillation and WPW syndrome, electrocardioversion must be performed if the situation is hemodynamically unstable. In hemodynamically stable conditions, pharmacologic therapy with a class Ic or class III antiarrhythmic agent may be attempted first. Beta-blockers, calcium antagonists acting on the AV node, and adenosine, on the other hand, are contraindicated in the acute situation with AF because they may block conduction in the AV node and thereby further promote conduction via the accessory pathway (paradoxical pulse acceleration).

Procedure for patients with asymptomatic preexcitation

In addition to patients with WPW syndrome (preexcitation and symptomatic tachycardia), there is also a group of patients with asymptomatic preexcitation without tachycardia, in whom preexcitation is usually discovered by chance. In these patients, noninvasive risk stratification by ergometry is generally recommended as the primary method. If sudden loss of preexcitation occurs during this process at elevated heart rates, there is a low risk of sudden cardiac death because of the long refractory period and generally no further action is required.

If this phenomenon cannot be observed or cannot be observed with certainty, the further procedure regarding electrophysiological examination and ablation must be discussed individually. Because of the high chance of success and the low risk of the examination, the indication for ablation in patients with asymptomatic preexcitation has become more generous in recent years. Furthermore, there are additional factors that tend to favor ablation: Registry data suggest that, first, sudden cardiac death in patients with WPW syndrome is more common during exercise and, second, that WPW syndrome may be responsible for about 1% of deaths in athletes [10]. Accordingly, ablation should be considered sooner in athletes. For professional drivers (truck, bus, train) and military trainees in Switzerland, the driving resp. Fitness for duty only given after prior ablation of the accessory pathway. Another group of patients with asymptomatic preexcitation in whom ablation should be considered is patients with structural heart disease, as they are at increased risk for atrial fibrillation and thus increased risk for sudden cardiac death.

Literature:

- Triedman JK: Management of asymptomatic Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Heart 2009; 95(19): 1628-1634.

- Klein GJ, et al: WPW pattern in the asymptomatic individual: has anything changed? Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2009; 2(2): 97-99.

- Munger TM, et al: A population study of the natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1953-1989. Circulation 1993; 87: 866-873.

- Keating L, Morris FP, Brady WJ: Electrocardiographic features of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Emerg Med J 2003; 20(5): 491-493.

- Attenhofer Jost CH, et al: Ebstein’s Anomaly. Circulation 2007; 115: 277-285.

- Al-Khatib SM, Pritchett ELC. Clinical features of Wolff-Parkinson White syndrome. Am Heart J 1999; 138: 403-413.

- Tischenko A, et al: When should we recommend catheter ablation for patients with the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome? Curr Opin Cardiol 2008; 23(1): 32-37.

- Jackman WM, et al. Catheter ablation of accessory atrioventricular pathways (Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome) by radiofrequency current. N Engl J Med 1991; 324: 1605-1611.

- Haissaguerre M, et al: Frequency of recurrent atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation of overt accessory pathways. Am J Cardiol 1992; 69(5): 493-497.

- Cohen MI, et al: PACES/HRS expert consensus statement on the management of the asymptomatic young patient with a Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW, ventricular preexcitation) electrocardiographic pattern: developed in partnership between the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS). Heart Rhythm 2012; 9(6): 1006-1024.

CARDIOVASC 2016; 15(6): 10-13