Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most common diseases in Western industrialized countries. New diagnostic methods and insights into pathophysiology (e.g. acid pocket), enable new therapies. Advanced training will focus on proton pump inhibitors (PPI) and alginate antacid preparations.

| Thanks to the sponsorship of the company Reckitt Benckiser, participation in this training is free of charge for you. The training has been prepared by professionals and produced with absolute respect for our editorial freedom. At no time did and does the company have any influence on the content of the training. All texts are subject only to the scientific sovereignty of the authors and the editorial staff of PPM MEDIC. |

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a medical condition defined by the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus and the resulting bothersome symptoms and/or complications [1]. It is one of the most common diseases in Western industrialized countries, with a prevalence of 10% to 20% and an incidence of about 5 per 1000 persons per year [2]. In fact, according to epidemiological surveys, prevalence has increased significantly over the past two decades, resulting in rising healthcare costs [3].

New diagnostic methods and related insights regarding pathophysiology, such as the postprandial development of an acid pocket, enable new therapies.

Pathogenesis and risk factors

GERD has a multifactorial pathogenesis, with impaired function of the antireflux barrier, consisting of the lower esophageal sphincter and diaphragmatic muscles, playing a crucial role [4]. Severe reflux disease is most commonly seen in patients with a large axial hiatal hernia. The most common cause of mild to moderate reflux is transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESR). In addition, factors such as decreased resting esophageal sphincter tone, ineffective esophageal motility with consecutive inadequate clearance, delayed gastric emptying, decreased salivary flow, or impaired tissue resistance may influence disease development [5].

Several risk factors may additionally promote the development of GERD. These include advanced age, obesity, alcohol consumption and smoking, as well as pregnancy [5,6]. Furthermore, various medications can lead to reflux disease. These include drugs that have a relaxing effect on the lower esophageal sphincter, such as calcium antagonists, anticholinergics, theophylline, and nitrates. Opiates and steroids, which cause gastroparesis, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which affect tissue resistance, may also increase the risk of GERD [7].

The clinical spectrum

The clinical picture encompasses a broad clinical spectrum that can be divided into different categories [8]:

- non-erosive reflux disease (NERD)

- erosive reflux esophagitis (ERD)

- Barrett’s esophagus

- Complications of GERD (e.g., peptic stenosis, esophageal adenocarcinoma).

- extraesophageal manifestations (e.g., globus, cough, hoarseness, dental erosions)

- hypersensitive esophagus

- Functional reflux complaints (i.e., no objective evidence of GERD).

Up to 70% of patients with typical GERD symptoms have a normal esophageal mucosa and can therefore be classified into the NERD subgroup [9]. This means that reflux of gastric acid causes symptoms but does not trigger endoscopically visible mucosal changes. In contrast, endoscopically detectable erosions of the mucosa are referred to as ERD.

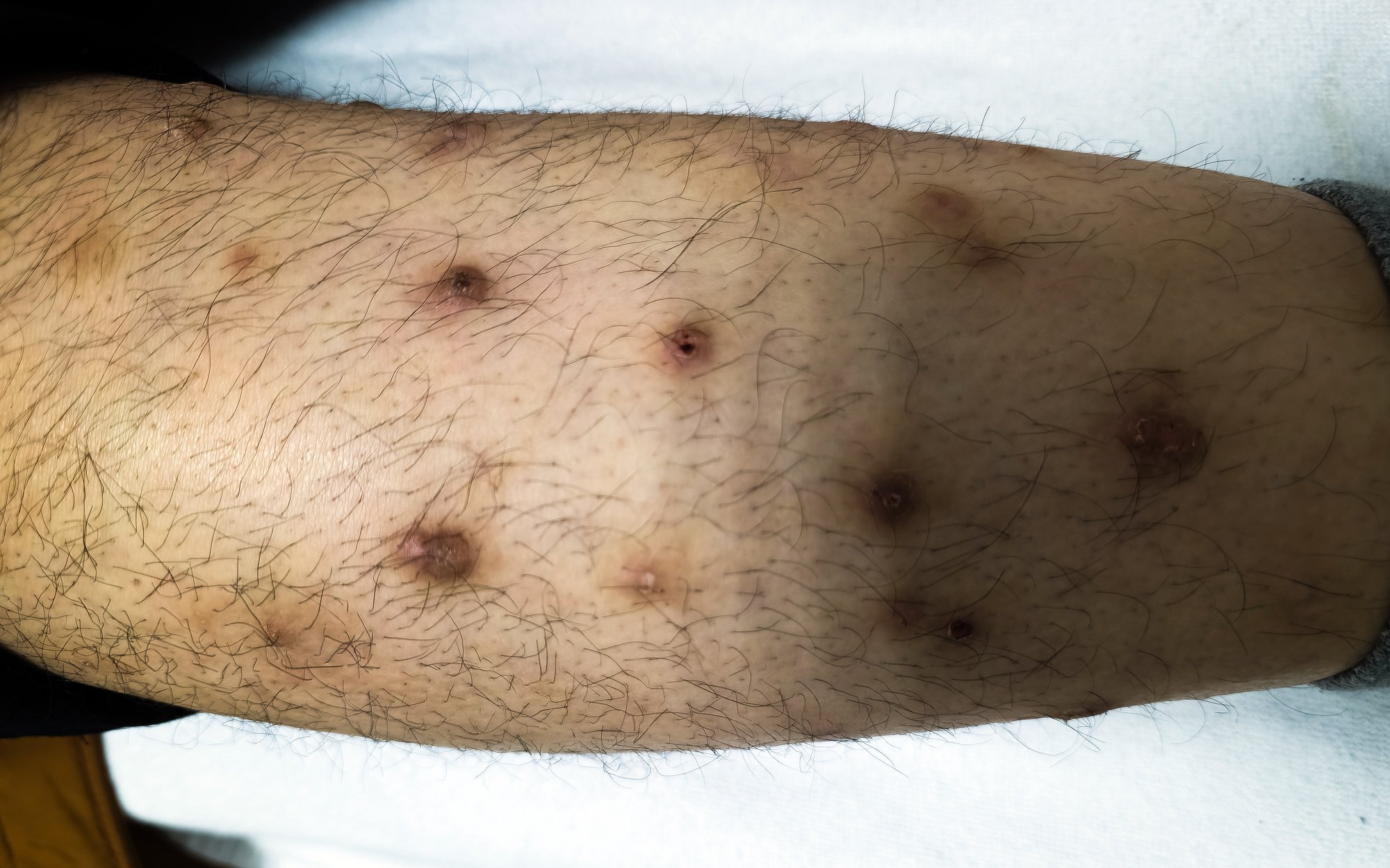

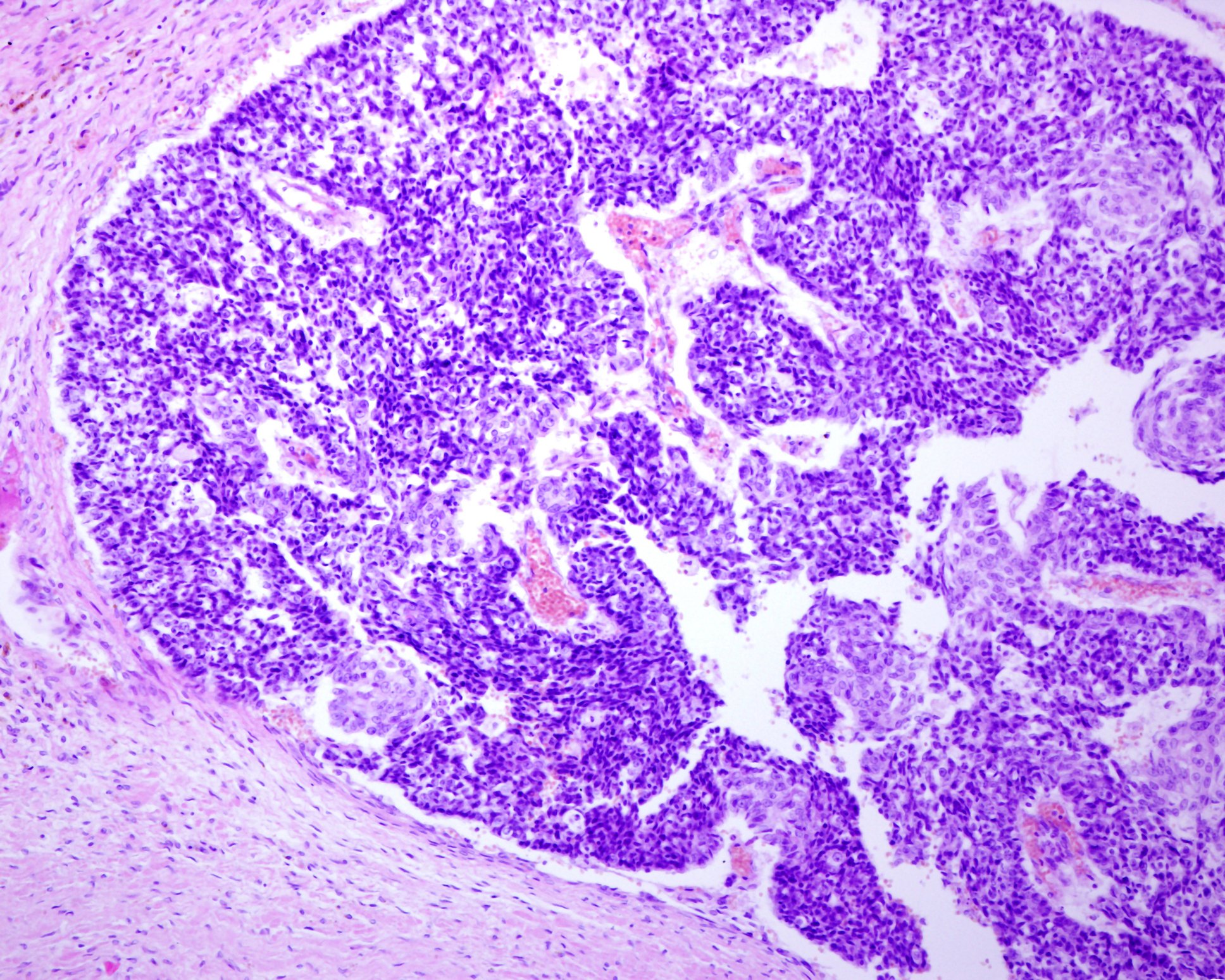

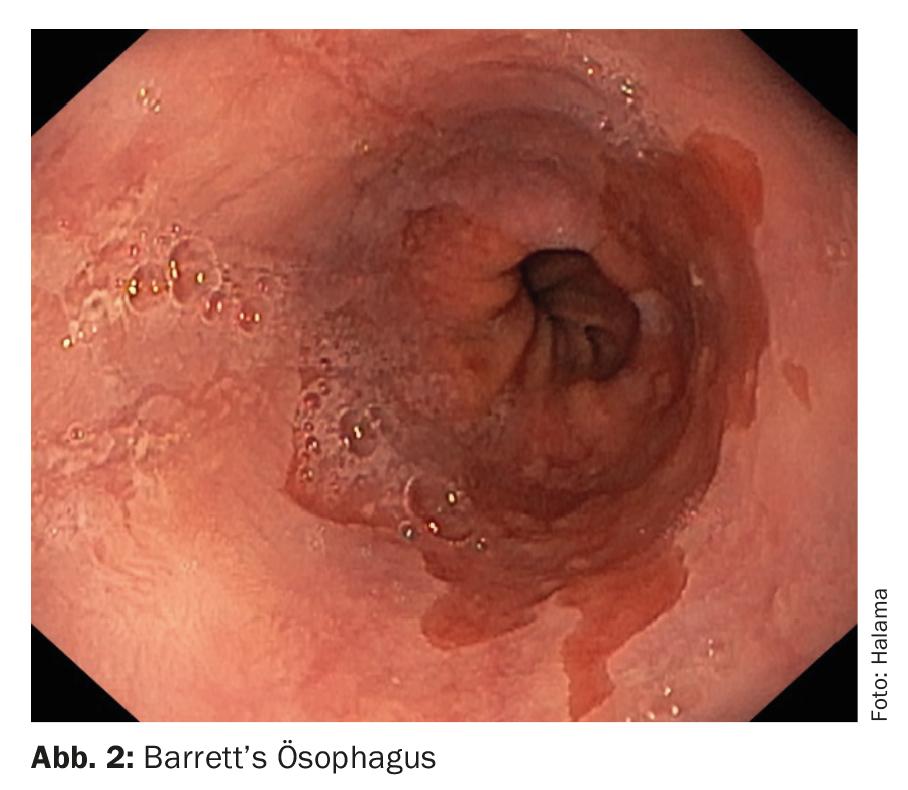

Barrett’s esophagus is found in 5-15% of patients undergoing endoscopy for chronic reflux symptoms. This is defined by the multilayered squamous esophageal epithelium metaplastically transforming into a single-layered, highly prismatic cylindrical epithelium. Barrett’s esophagus is a precancerous condition with a 0.5% per patient-year risk of developing adenocarcinoma. However, a not insignificant proportion of patients with Barrett’s esophagus (Fig. 2) are asymptomatic and therefore difficult to diagnose in time [10].

Complications of GERD can manifest both inside and outside the esophagus. In the esophagus, esophagitis, stenosis, or Barrett’s esophagus, described earlier, may occur. Extraesophageal complications include laryngitis, chronic cough, nonatopic asthma, and dental erosions. A possible association also exists between GERD and pharyngitis, sinusitis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and recurrent otitis media.

Hypersensitive esophagus describes patients who have increased symptom awareness due to increased sensitivity, although reflux events are formally within the norm. The lowering of the esophageal pain threshold can have both central nervous and peripheral causes. Endoscopically detectable erosive changes are not present in hypersensitive esophagus. Symptoms can have a variety of causes, including distension of the esophagus from reflux or chemical stimulation from acid. The perception of symptoms may be exacerbated by physical stress (e.g., sleep deprivation in shift workers) or anxiety disorders, in which case esophageal symptoms may occur even in the absence of physiologic or pathologic esophageal stimulation [11].

Diagnostics

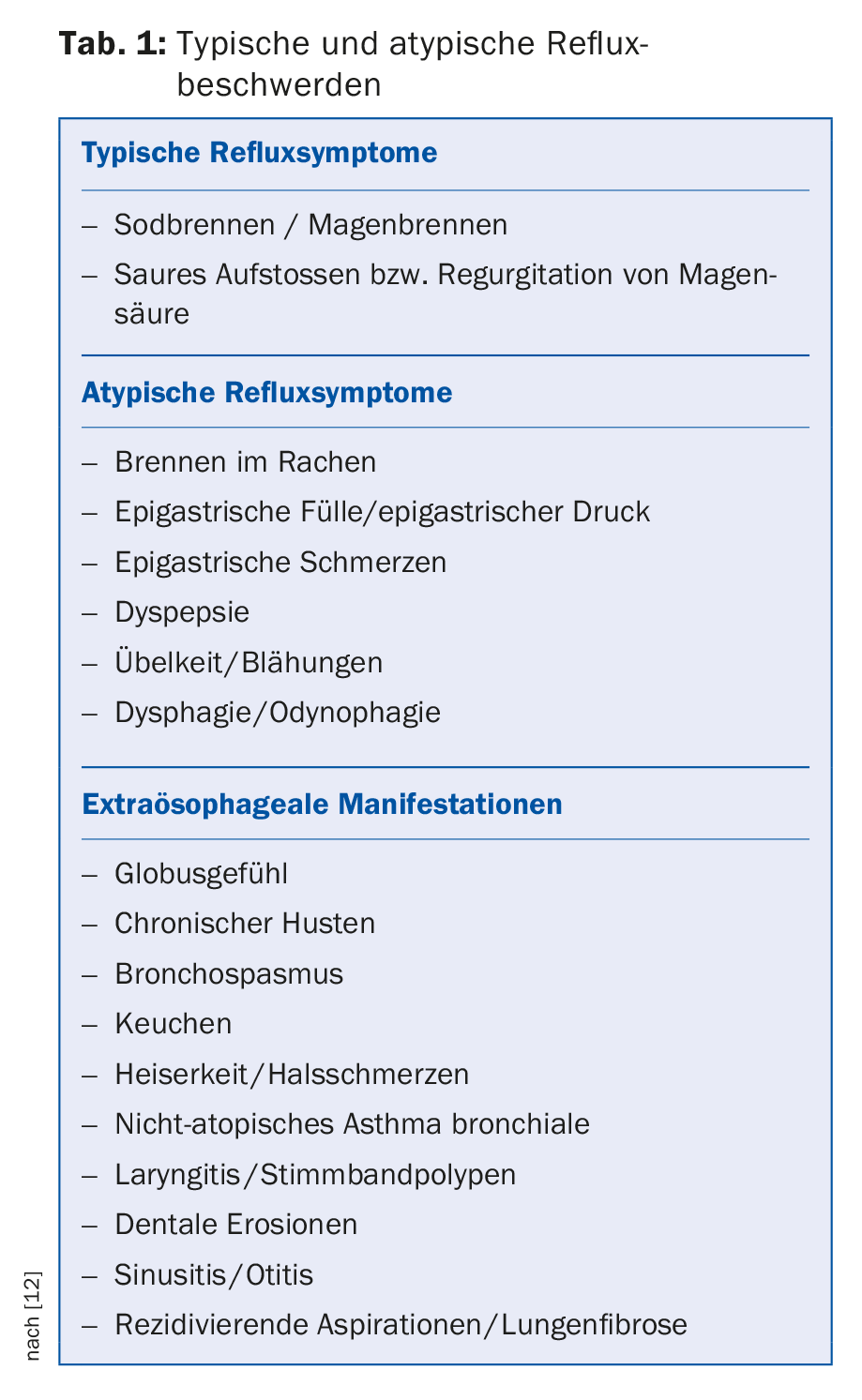

A differentiated medical history is crucial for the diagnosis of GERD. This first involves recording the symptoms (tab. 1) . The typical reflux symptoms are gastric burning and acid regurgitation. However, other symptoms such as epigastric pain, thoracic pain, difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), painful swallowing (odynophagia), burning in the throat, or increased throat clearing may also be associated with GERD. Apart from recording the symptoms, a clarification of other complaints in the gastrointestinal tract (e.g., symptoms of an irritable stomach or intestine) should continue to be performed and a detailed medication history should be obtained [8].

If patients experience typical reflux symptoms once or twice a week, which in turn lead to impaired quality of life, GERD is considered likely. If no alarm symptoms such as dysphagia, odynophagia, involuntary weight loss, or anemia are present, empiric therapy with proton pump inhibitors (PPI) can be initially given without further diagnostic testing.

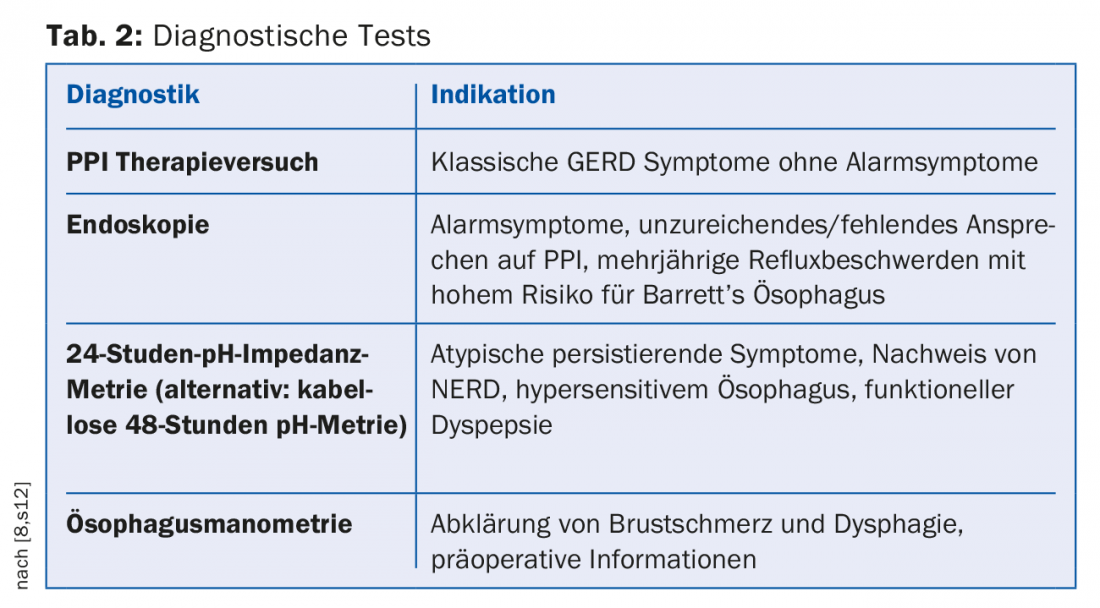

Further diagnostics are required if patients present with alarm symptoms, do not respond to PPI therapy, or the symptoms have been present for a prolonged period of time (Tab. 2) [12].

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy provides the opportunity to evaluate changes in the esophageal mucosa and obtain mucosal biopsies as needed. It is especially necessary when alarm symptoms are present. In contrast, general endoscopic screening of patients with GERD symptoms is not recommended [8].

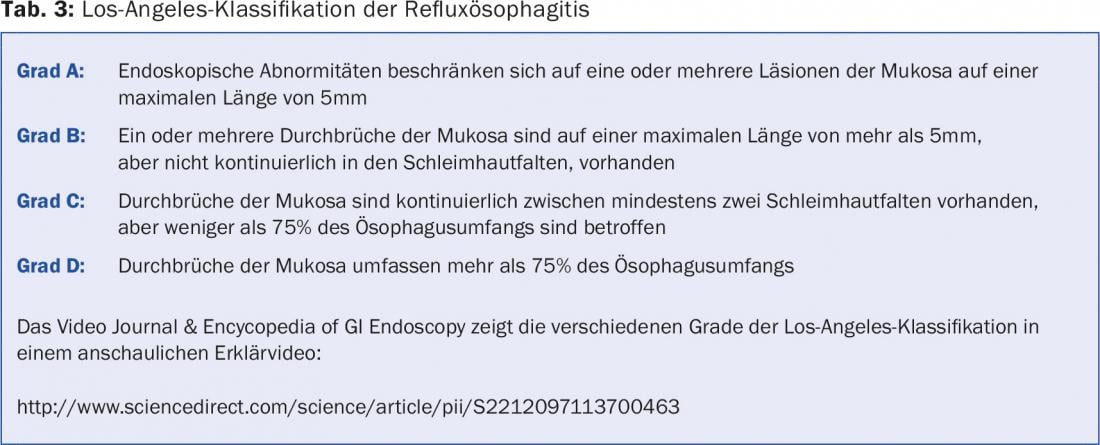

If patchy, streaky, or circularly confluent epithelial defects (erosions) are detected by endoscopy, classification of reflux esophagitis should be based on the Los-Angeles criteria. It should be noted that grade A and B reflux esophagitis (Table 3) can be found in at least 15% of the general population [13].

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212097113700463#cesec50

In addition, other findings such as stenosis, ulcer, Schatzki’s ring, metaplasia, or hiatal hernias should be documented in the report of findings. In contrast, other abnormalities such as erythema, granulation, an indistinct transition of the mucosal area from squamous to cylindrical epithelium, increased vascular markings in the distal esophagus, edema, or prominence of the mucosal folds are not diagnostically relevant [8].

If erosions or NERD are present, mucosal biopsies do not need to be taken. However, if eosinophilic esophagitis is suspected, at least four to six biopsies should be obtained from different heights of the esophagus.

If the reflux symptoms have been present for several years, endoscopy is required to rule out Barrett’s esophagus. Barrett’s esophagus is diagnosed based on histologic evidence of specialized intestinal metaplastic cylinder epithelium. Endoscopic description should be based on the Prague classification, which includes an indication of circumferential (C) and maximal (M) extent of cylinder epithelial metaplasia. In addition, targeted biopsy of suspicious mucosal areas followed by four-quadrant biopsy every 1-2 cm is required to allow localization of the neoplastic area. If inflammatory changes are present, the four-quadrant biopsy should be performed again after four weeks of PPI therapy. If low-grade or high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia or mucosal carcinoma is detected in Barrett’s esophagus, endoscopic resection should be performed [8].

24-hour pH-metry or combined pH-impedance measurement is typically used in patients with atypical reflux symptoms, extraesophageal manifestations, or persistent symptoms, especially in the absence of endoscopic evidence for GERD. Thus, it plays an important role in the diagnosis of NERD. By means of this method, statements can be made about the presence of pathological reflux, the type of reflux and the duration of reflux episodes. It is the only way to establish a direct link between symptoms and acid reflux episodes [12]. Thus, it can be used to diagnose hypersensitive esophagus or functional dyspepsia. Especially in hypersensitive esophagus, the correlation of symptoms and reflux episodes is crucial, as this diagnosis suggests a physiological number of reflux episodes with concomitant perception of an increased number.

Esophageal manometry is not suitable for the diagnosis of reflux disease alone. Nevertheless, it can be used to clarify chest pain and dysphagia.

In addition, it should be used preoperatively to obtain information on the localization of the lower esophageal sphincter or characterization of tubular motility, as well as to rule out relevant differential diagnoses such as achalasia or hypomotility in scleroderma [8].

Measurement of duodenogastroesophageal reflux, radiographic studies, or scintigraphy should not be performed because of their low sensitivity [8].

Therapies

Lifestyle changes can help improve reflux symptoms. This includes avoiding late-night meals and avoiding individually intolerable foods and beverages. Weight reduction is recommended for overweight patients. In addition, raising the head end of the bed can relieve symptoms.

The main goal of drug therapy is satisfactory control of GERD symptoms regardless of clinical manifestation. In addition, endoscopically proven reflux esophagitis should heal the lesions and prevent the occurrence of complication such as bleeding, stenosis, or carcinoma.

Proton pump inhibitors

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are medications used for acid suppression. They block the function of H+/K+-ATPase in the gastric vestibular cells and thus prevent the secretion of gastric acid. This provides relief from the symptoms.

In typical reflux syndrome with unknown endoscopic findings, empiric treatment with the standard dose of PPI for four weeks is recommended. The same is true for symptomatic or asymptomatic mild reflux esophagitis, which can be classified by Los Angeles grade A or B. Subsequently, if necessary, a switch to an “on-demand” therapy with half the standard dose can be made. Patients with NERD should also receive half a standard dose of PPI for four weeks, although the dose may be increased or the duration of therapy extended if the response to this therapy is inadequate [8]. In addition, the use of another PPI is possible. Full-dose PPI therapy for four weeks can usually achieve adequate symptom control and healing of any lesions in patients with NERD or erosive esophagitis.

PPIs may also be used in long-term therapy. This can be intermittent, continuous, or on-demand. In this case, however, the lowest effective dose should be determined on the basis of a gradual dose reduction (step down). In the case of long-term stable remission in the context of continuous therapy, a discontinuation attempt is also possible [8]. If symptomatic or asymptomatic severe Los Angeles grade C or D reflux esophagitis is present, continuous therapy with PPI medications at standard doses is advised (twice daily for persistent inflammation and/or symptoms) [8].

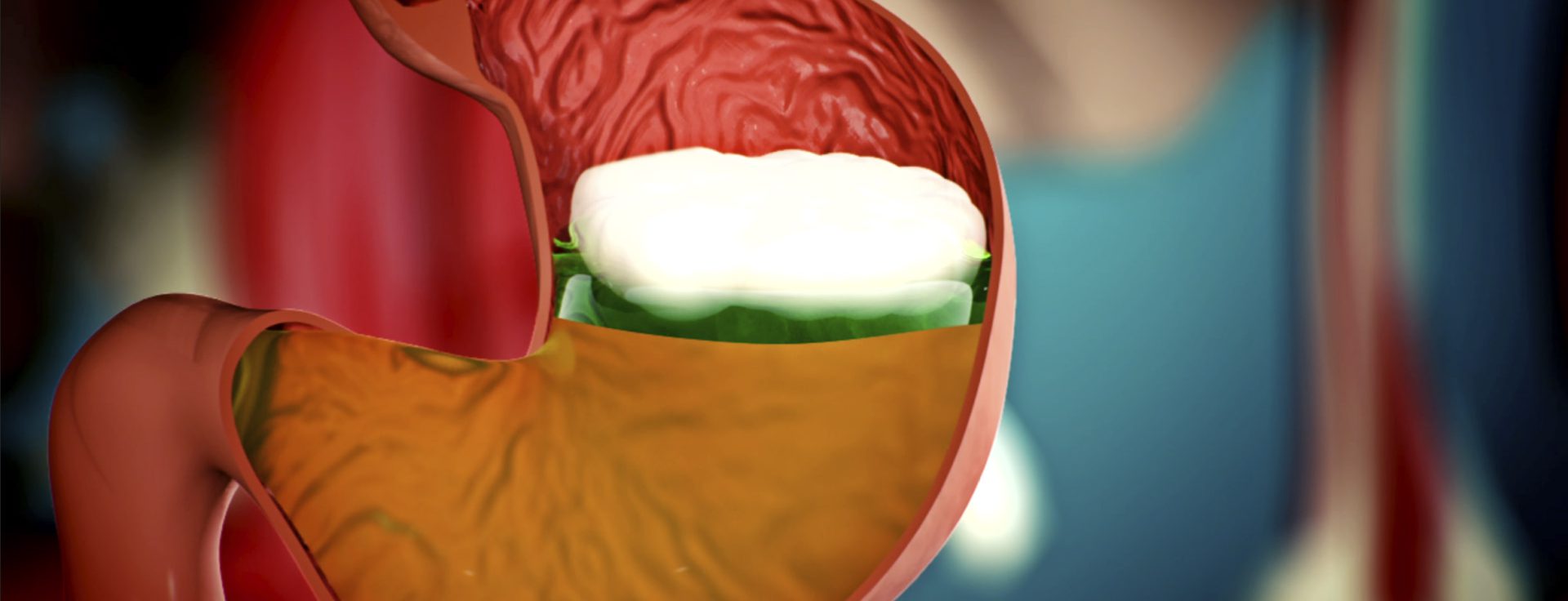

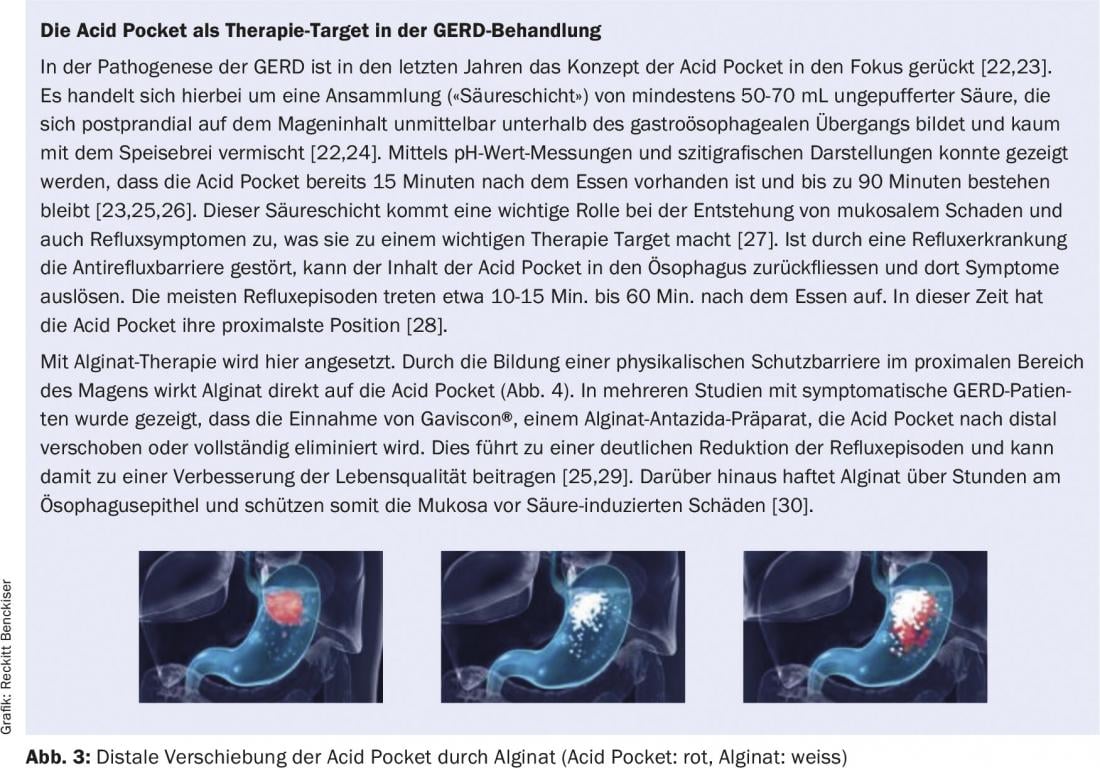

Alginate

Alginate antacid preparations allow symptom control even without acid suppression. Within minutes of ingestion, alginate antacid preparations, such as Gaviscon®, form a gel-like layer on the surface of the acid accumulation in the stomach by contact with gastric acid, thereby mechanically preventing reflux episodes [14,15]. This physical protective barrier in front of the gastroesophageal junction suppresses acid and nonacid reflux episodes during the day and also in the supine position [14,16]. In addition, alginate adheres to the esophageal epithelium, where it forms a protective layer that can relieve symptoms over time.

Thus, alginate provides an alternative treatment for persistent reflux symptoms. Alginate can also be used for symptom control in the step-down process when tapering off the PPI. In addition, combination with PPI is possible to provide more effective symptom relief [17,18].

Other drugs

Although antacids are inferior in efficacy to PPIs and alginate, they can be used when necessary. This includes individual cases or as-needed therapy in patients with NERD. In addition, treatment of pregnant women is also possible. For mild symptoms in pregnancy, initial therapy can be with an antacid. However, if this treatment does not respond or if severe symptoms are present, PPI should be prescribed [8]. Since antacids only serve to neutralize acid, they cannot reduce the number of reflux episodes and have no effect on the acid pocket. Prokinetic drugs such as domperidone or baclofen can also prevent gastroesophageal reflux by increasing the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter and accelerating gastric emptying [7].

Tricyclic antidepressants (TADs) and serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) serve to decrease esophageal mucosal sensitivity and therefore may be used to treat hypersensitive esophagus and functional gastric distress. Both sole prescription and combination therapy with a PPI are possible [8].

H2 receptor antagonists play a rather minor role in GERD therapy in Switzerland.

Surgical therapy

Surgical intervention should only be performed if there is a long-term need for therapy. In addition, surgery may be required if the indication criteria are also met, intolerable reflux-induced residual symptoms occur, or PPI intolerance exists. Prior to such surgery, pathologic reflux must be demonstrated by 24-hour pH-metry impedance measurement and esophageal manometry must be performed to rule out motility disorder. If antireflux surgery is indicated, laparoscopic fundoplication is the preferred procedure. The therapeutic success is comparable to that of PPI therapy [8].

Add-on therapy with alginate

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) play a critical role in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Their efficacy over placebo treatments and superiority over other drugs has been demonstrated in numerous studies [19]. Nevertheless, there are always patients who do not respond to PPI therapy. Randomized trials show that the proportion of patients with persistent GERD symptoms despite PPI treatment is about 30% [20]. Similar numbers are seen in the long-term treatment of chronic reflux symptoms. In a survey of 333 patients who had been receiving PPI therapy for at least one year, 46% reported experiencing gastric burning and/or regurgitation on at least two days per week [21].

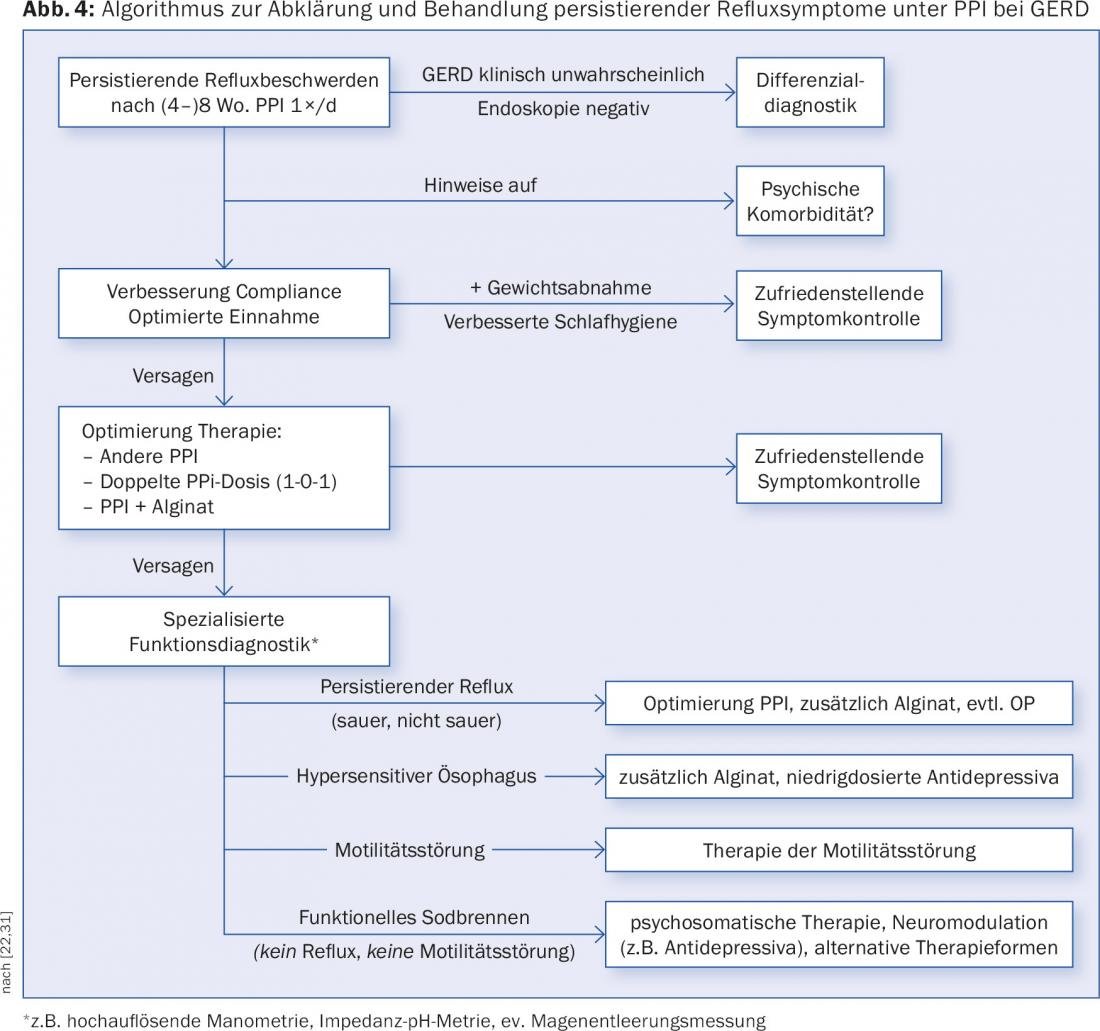

In case of reflux symptoms despite adequate PPI therapy, the further procedure should be adjusted accordingly. For this reason, a current algorithm has been published (Fig. 4), which presents the workup and treatment of persistent reflux symptoms under PPI in GERD [22].

An important first step is to confirm the diagnosis of GERD. If PPIs were prescribed based only on clinical symptoms, further differential diagnosis should be performed. Both a careful history and an additional endoscopy, if this had not yet been performed, are required. If there is no macroscopic explanation for the complaints, it is also advisable to take biopsies from the duodenum, stomach and esophagus. In individual cases, psychological comorbidities may also play a role and should be considered [22].

If GERD has been detected, work can first be done with the patient to improve compliance and/or optimize intake. Changes in lifestyle habits, such as adequate night’s rest or weight reduction in overweight patients, may also contribute to satisfactory symptom control [22].

If these measures do not lead to the desired success, a change of the PPI preparation and/or an increase of the dose are possibilities to optimize the therapy [22]. However, due to the fact that in many patients PPI therapy alone is not sufficient to effectively alleviate symptoms, an add-on treatment with alginate is recommended at this point (see box “The Acid Pocket as a therapy target in GERD treatment”). In patients with non-erosive reflux disease (NERD), a combination with alginate leads to a significant improvement in symptoms compared to PPI monotherapy (omeprazole) [32].

If symptoms persist, presentation to a gastroenterologist for further clarification by specialized functional diagnostics is advised [22]. Important differential diagnoses here are:

- a hypersensitive esophagus

- Motility disorders of the esophagus

- functional heartburn

According to the diagnosis, adapted or further therapy options can then be considered.

Antacids and alginate in the step-down process

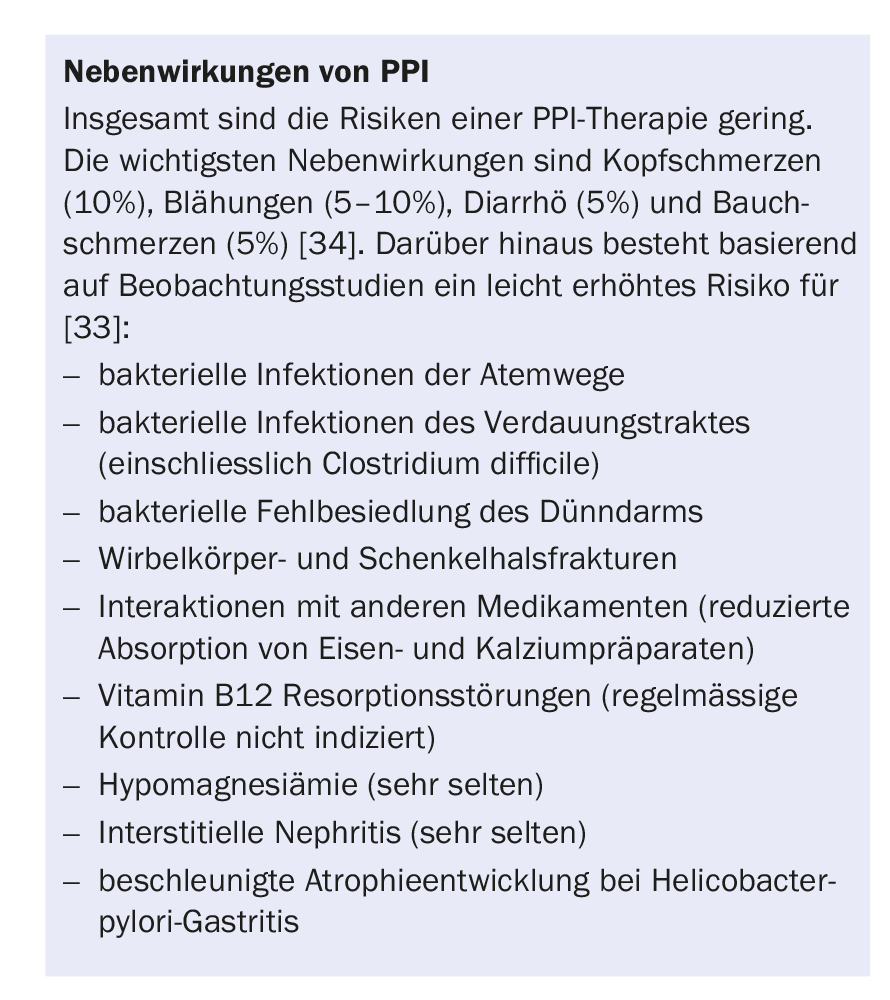

Although PPIs are mostly very well tolerated, side effects can occur (box “Side effects of PPIs”). Nevertheless, PPI are usually used in prolonged or permanent treatment of GERD. However, a gradual dose reduction should be used to determine the lowest effective dose in order to minimize the risk of adverse effects. In the case of long-term stable remission under continuous PPI therapy, even a discontinuation attempt can be made [8].

Both during gradual dose reduction, the so-called step-down process, and when discontinuing PPIs in the step-off process, additional symptom-oriented treatment is useful. As shown in placebo-controlled studies in healthy subjects, abrupt discontinuation of PPI after four or eight weeks of treatment results in acid rebound with an increased risk of dyspeptic symptoms [34,35]. Although the value of these outcomes in patients with reflux disease is controversial, the risk for symptomatic acid rebound should be minimized. Therefore, in addition to gradual dose reduction, the use of an antacid or alginate as needed is advised [36].

Take-Home Messages

- In cases of typical reflux symptoms without alarm symptoms, empiric therapy with proton pump inhibitors (PPI) can be performed without further diagnostics.

- In case of alarm symptoms, non-response to PPI therapy or long-term complaints, further diagnostics are required. If a definitive diagnosis is not established on endoscopy, then 24-hour combined pH impedance measurement should be considered.

- An alginate antacid preparation can be used in combination with PPI as well as monotherapy for PPI intolerance or during PPI tapering for symptom control in the step-down and step-off process.

- Surgical therapy is indicated only in cases of long-term therapeutic need, intolerable residual symptoms, or PPI intolerance.

Literature:

- Vakil N, et al: The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol, 2006. 101(8): 1900-1920.

- Dent J, et al: Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut, 2005. 54(5): 710-717.

- El-Serag HB: Time trends of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2007. 5(1): 17-26.

- Labenz J: Gastroesophageal reflux disease. DGIM Internal Medicine, 2015: 1-11.

- Bredenoord AJ, Pandolfino JE, Smout AJ: Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. The Lancet, 2013. 381(9881): 1933-1942.

- Fox M, Forgacs I: Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 2006. 332(7533): 88.

- Halama M, Frühauf H: Reflux and functional diseases of the esophagus – a common disease? ARS MEDICI, 2010. 21: 852-857.

- Koop H, et al: S2k guideline: gastroesophageal reflux disease under the auspices of the German Society of Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS). Z Gastroenterol, 2014. 52: 1299-1346.

- Martinez SD, et al: Non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) – acid reflux and symptom patterns. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2003. 17(4): 537-545.

- Shaheen NJ, Judge JE: Barrett’s oesophagus. The Lancet, 2009. 373(9666): 850-861.

- Gyawali CP: Esophageal hypersensitivity. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 2010. 6(8): 497.

- Badillo R, Francis D: Diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther, 2014. 5(3): 105-112.

- Ronkainen J, et al: Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in the general population: an endoscopic study. Gastroenterology, 2005. 129(6): 1825-1831.

- Sweis R, et al: Post-prandial reflux suppression by a raft-forming alginate (Gaviscon Advance) compared to a simple antacid documented by magnetic resonance imaging and pH-impedance monitoring: mechanistic assessment in healthy volunteers and randomised, controlled, double-blind study in reflux patients. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 2013. 37(11): 1093-1102.

- Rohof WO, et al: An alginate-antacid formulation localizes to the acid pocket to reduce acid reflux in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2013. 11(12): 1585-1591.

- De Ruigh A, et al: Gaviscon Double Action Liquid (antacid & alginate) is more effective than antacid in controlling post-prandial esophageal acid exposure in GERD patients: a double-blind crossover study. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 2014. 40(5): 531-537.

- Reimer C, et al: Randomised clinical trial: alginate (Gaviscon Advance) vs. placebo as add-on therapy in reflux patients with inadequate response to a once daily proton pump inhibitor. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2016.

- Labenz J, Koop H: Gastroesophageal reflux disease-what to do when PPIs are not sufficiently effective, tolerated, or desired? DMW-German Medical Weekly, 2017. 142(05): 356-366.

- Mössner J: The Indications, Applications, and Risks of Proton Pump Inhibitors: A Review After 25 Years. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 2016. 113(27-28): 477.

- El-Serag H, Becher A, Jones R: Systematic review: persistent reflux symptoms on proton pump inhibitor therapy in primary care and community studies. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 2010. 32(6): 720-737.

- Labenz J, et al: Inadequate symptom control under long-term PPI therapy for GERD – fact or fiction? MMW Advances in Medicine, 2016. 158(4): 7-11.

- Labenz J, Koop H: Gastroesophageal reflux disease-what to do when PPIs are not sufficiently effective, tolerated, or desired? DMW-German Medical Weekly, 2017. 142(05): 356-366.

- Kahrilas PJ, et al: The acid pocket: a target for treatment in reflux disease? The American journal of gastroenterology, 2013. 108(7): 1058-1064.

- Steingoetter A., et al: Volume, distribution and acidity of gastric secretion on and off proton pump inhibitor treatment: a randomized double-blind controlled study in patients with gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) and healthy subjects. BMC gastroenterology, 2015. 15(1): 111.

- Rohof, W.O., et al: An alginate-antacid formulation localizes to the acid pocket to reduce acid reflux in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2013. 11(12): 1585-1591.

- Fletcher J, et al: Unbuffered highly acidic gastric juice exists at the gastroesophageal junction after a meal. Gastroenterology, 2001. 121(4): 775-783.

- Boeckxstaens G, et al: Symptomatic reflux disease: the present, the past and the future. Gut, 2014: gutjnl-2013-306393.

- Rohof W, et al: Effect of azithromycin on acid reflux, hiatus hernia and proximal acid pocket in the postprandial period. Gut, 2012: gutjnl-2011-300926.

- Kwiatek MA, et al: An alginate-antacid formulation (Gaviscon Double Action Liquid) can eliminate or displace the postprandial “acid pocket” in symptomatic GERD patients. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 2011. 34(1): 59-66.

- Woodland, P., et al: Topical protection of human esophageal mucosal integrity. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 2015. 308(12): G975-G980.

- Heinrich H, Fox M, Schwizer W: Diagnosis and therapy in gastroesophageal reflux: Reflux – a common disease? Family Practice, 2014. 9(9): 26-30.

- Manabe N, et al: Efficacy of adding sodium alginate to omeprazole in patients with nonerosive reflux disease: a randomized clinical trial. Diseases of the Esophagus, 2012. 25(5): 373-380.

- Halama M, Frühauf H: Reflux and functional diseases of the esophagus – a common disease? ARS MEDICI, 2010. 21: 852-857.

- Niklasson A, et al: Dyspeptic symptom development after discontinuation of a proton pump inhibitor: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. The American journal of gastroenterology, 2010. 105(7): 1531-1537.

- Reimer C., et al: Proton-pump inhibitor therapy induces acid-related symptoms in healthy volunteers after withdrawal of therapy. Gastroenterology, 2009. 137(1): 80-87. e1.

- Cawston J, Evans N: Dyspepsia: key considerations for cost-effective management. Prescriber, 2007. 18(5): 21-30.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(6): 24-31