Pathognomonic skin signs of dermatomyositis include heliotrope erythema, Gottron papules, and Gottron signs. The determination of myositis-specific autoantibodies has an increasingly important role in the diagnosis. Regarding treatment options, intravenous immunoglobulins have recently been officially approved in Switzerland. Corticosteroids and conventional basic therapeutics are still considered the standard of care. Biologics and small molecules are used in off-label use.

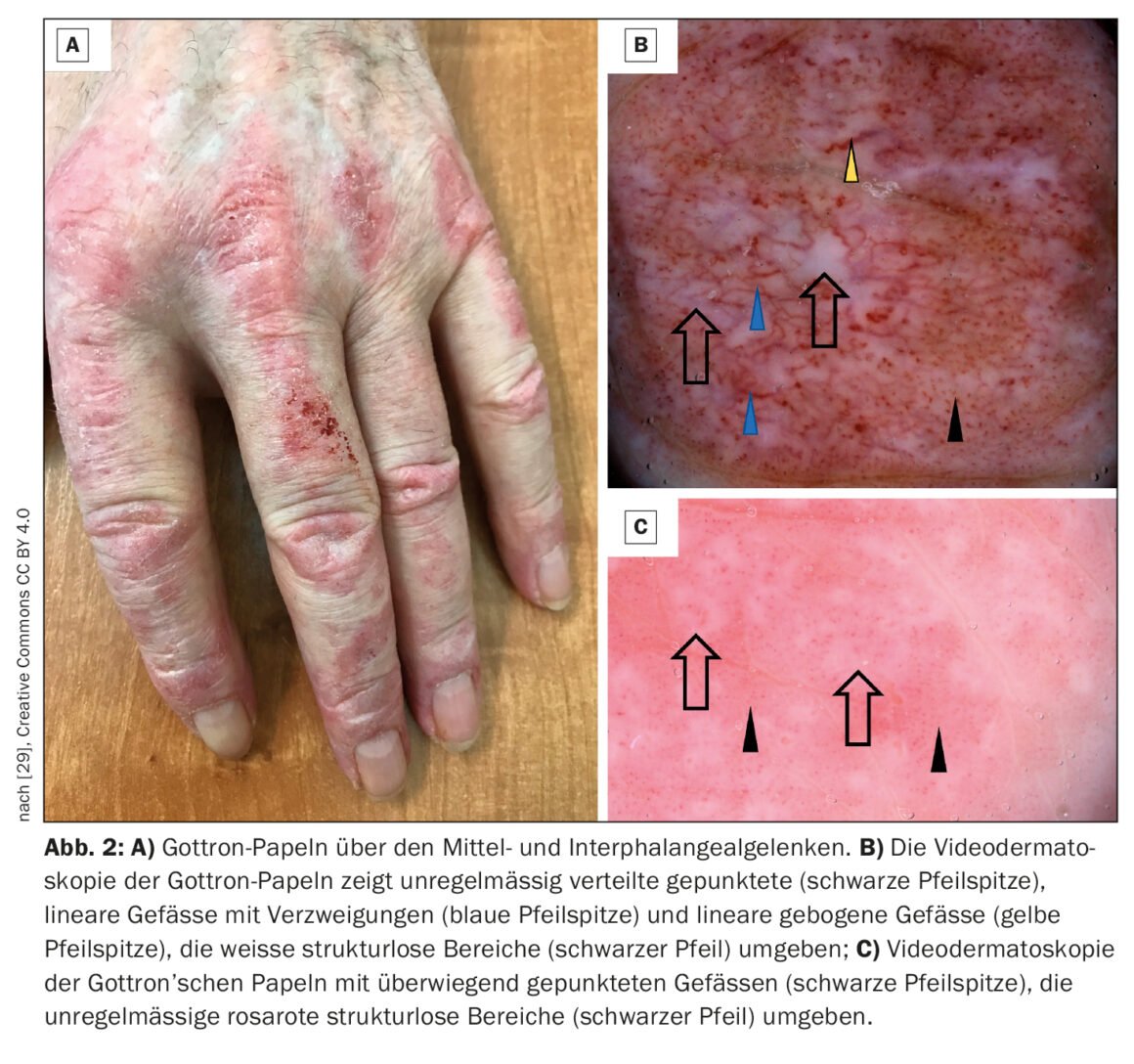

Dermatomyositis (DM) is an autoimmune disease belonging to the group of idiopathic inflammatory myositides (box) , which can start in childhood but can also appear in old adulthood [1–3]. The highest incidence rates have been documented between the ages of 5 and 14 (juvenile DM) and 45 and 50. Women are affected about twice as often as men, and a familial association is not known [4]. Muscle involvement results in inflammatory muscle destruction, which can lead to varying degrees of muscle weakness, particularly of the muscles of the shoulder and pelvic girdle that are close to the trunk. Classic signs on the skin include heliotropic rash (Fig. 1), cheek erythema, Gottron’s sign (Fig. 2) , and nail bed changes. In addition to muscle weakness and typical skin changes, cardiac and pulmonary involvement sometimes occurs. Prof. Dr. med. Britta Maurer, Clinic Director and Chief Physician, Clinic for Rheumatology, Inselspital Bern, gave an up-to-date overview of the diagnosis and treatment of dermatomyositis [5].

Myositis-specific autoantibodies, MRI, and biopsy as appropriate.

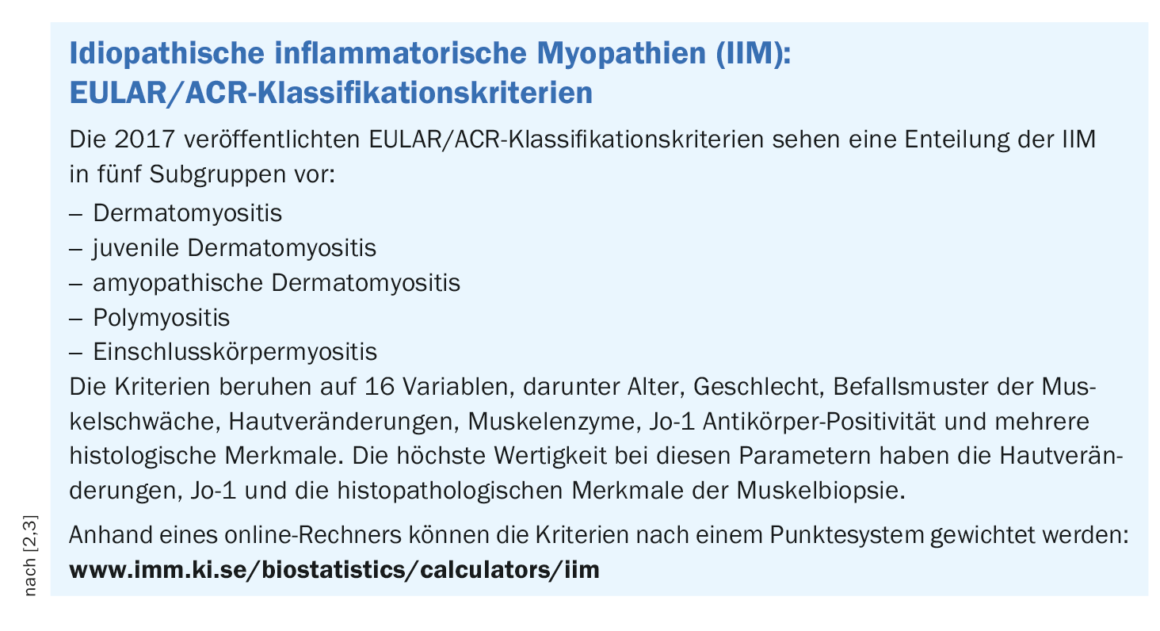

In the pathogenesis of dermatomyositis, complement-mediated microangiopathy with perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates of the skin and muscles play a crucial role [6]. In a classification of European and American professional societies (EULAR, ACR), clinical and laboratory examination parameters are used to calculate the probability of the diagnosis of DM (box) [2,3,7].

www.imm.ki.se/biostatistics/calculators/iim

The myolysis parameters creatine kinase (CK), myoglobin, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) are often only slightly elevated or even normal in DM [4]. The detection of certain autoantibodies is associated with different phenotypic manifestations of dermatomyositis (Table 1). However, for about 30% of all DM cases, no autoantibodies can be detected in the serum of the patients [8].

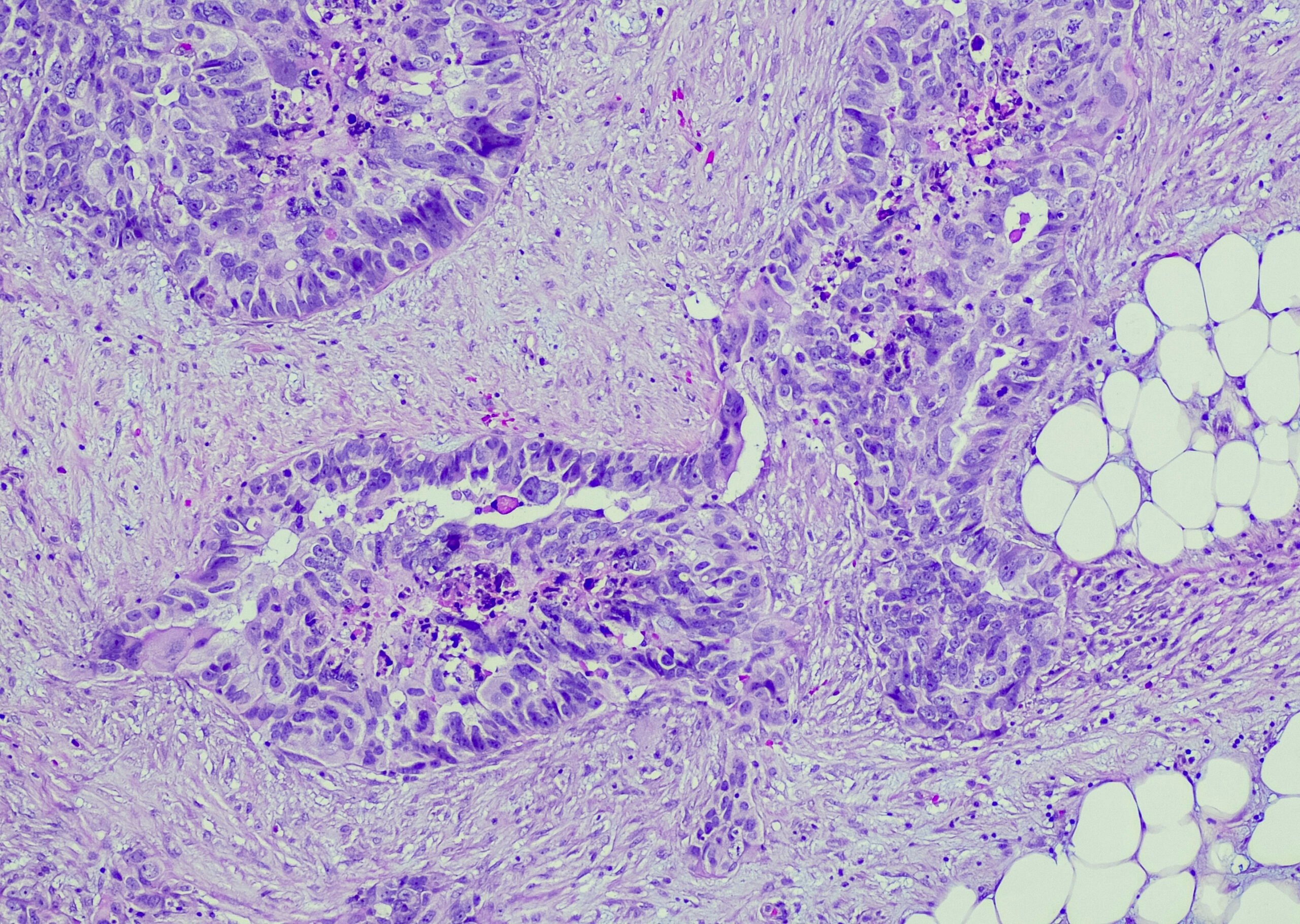

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to visualize inflammatory muscle infiltrates. Biopsies are particularly helpful in unclear cases. On the basis of a muscle biopsy, the detection of inflammatory, perivascular and/or perifascicular infiltrates is possible. Histopathologic findings of skin lesions in DM include vacuolar degeneration of basal keratinocytes, lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrates around skin blood vessels, and interstitial mucin deposits [9].

Tumor screening is recommended in all forms of DM because of a statistically increased risk (review 1) [7]. The majority of tumor screening is performed in the first year after diagnosis of DM and up to three years after diagnosis, as tumor manifestation is most common during this period.

Corticosteroids in the induction phase – steroid-sparing strategy in the course.

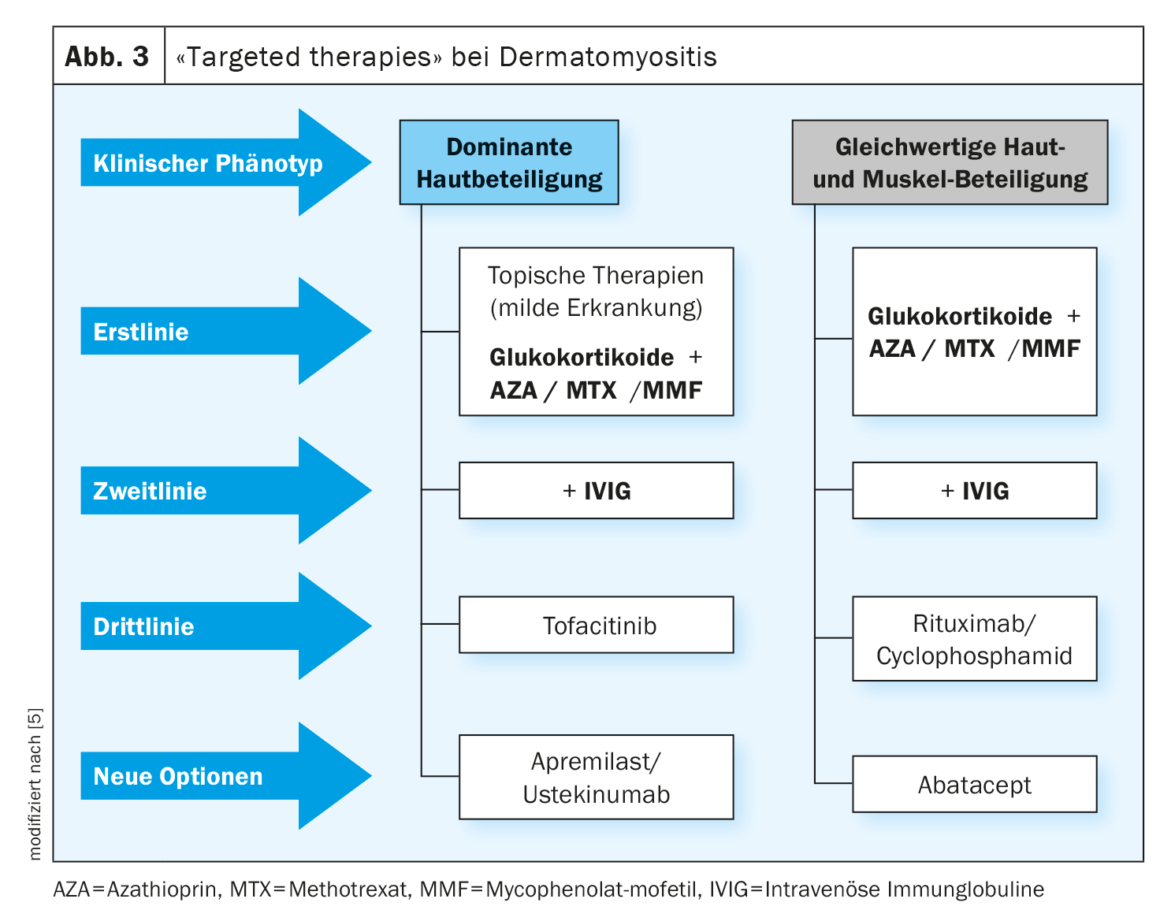

Glucocorticosteroids are first-line agents for DM (Fig. 3) [8]. In the acute phase, 1 mg/kg bw daily is started until clinical improvement, after which the dose is slowly reduced. Most patients initially respond well, but in order to save steroids, an additional immunosuppressant should be administered after 6 months at the latest; combination therapy can be considered initially, particularly in severe forms of the disease (Fig. 3) .

Glucocorticosteroids plus azathrioprine is the most common combination in the therapy of DM [8]. Azathioprine should be administered additively at a dosage of 1-3 mg/kg bw, especially in severe courses, e.g., generalized weakness, respiratory muscle involvement, or swallowing involvement, even initially, but has a known latency of 3-6 months to onset of action.

Methotrexate (MTX) is at least equal to AZA in DM with marked skin involvement and is preferred to AZA in jDM with normal renal function. MTX is a folic acid antagonist and is faster acting than AZA at doses of 15-25 mg/week, but is also in a higher toxicity class. Pneumonitis occasionally occurs as a side effect.

In the event of AZA failure or toxic liver injury resulting therefrom, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF, 2 g/d) may be used as an alternative. The current guideline [8] references several case reports supporting the utility of this treatment option [13–15]. MMF selectively blocks purine synthesis in lymphocytes, thereby inhibiting their proliferation. Most important side effects are chronic diarrhea, hemolytic anemia, and edema.

IVIG now officially approved by Swissmedic

In patients who respond inadequately to glucocorticoids/AZA, a therapeutic trial with intravenous immunoglobulins is useful (Fig. 3). There is convincing evidence of efficacy for IVIG (Octagam®), which was confirmed in the double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III pivotal study ProDERM [18,19]. In Switzerland, Octagam® received an indication extension from Swissmedic in February 2023 for the treatment of DM in adults [30].

For refractory courses, guideline recommends rituximab

Rituximab (RTX), an anti-CD20 antibody used off-label in DM in Switzerland, has shown promise in refractory cases (Fig. 3) [16]. Regarding dosage, the guideline recommends using the “immunologic regimen” with 2× 1000 mg i.v. at 14-day intervals, with repeat administration after approximately 6-9 months if deemed necessary based on the clinical course. Patients in the GRAID-2 registry received an average of 3.09 infusions [16,17]. No particular safety concerns arose in these patients, and most of them showed good tolerability. Infections are the most important adverse side effects of rituximab therapy [16,17].

If these therapy strategies are not effective: what else is available?

In a small study, abatacept, which is one of the biologics, showed promising results in reducing disease activity in adult patients with refractory dermatomyositis [21]. After six months of treatment with abatacept, muscle biopsies showed an increase in anti-inflammatory fork-head box P3 (FoxP3)+ regulatory T (Treg) cells, indicating muscle regeneration and response to treatment [21]. Tang et al. investigated the effects of abatacept in patients with myositis using a dataset from the ARTEMIS study and found that the CD4/CD8 ratio in the bloodstream at the time of active disease may be a predictor of treatment efficacy [22]. The investigation of the efficacy and safety of abatacept in dermatomyositis is the subject of several recent studies [16].

Several case reports are available on treatment with tofacitinib, a JAK inhibitor, including two dermatomyositis patients with calcinosis and interstitial lung disease who were treated with tofacitinib for 28 weeks and showed a very good response. No new calcifications occurred in either patient, treatment with tofacitinib was well tolerated, and no major safety problems occurred [23]. In another case report, an adult patient with anti-MDA-5 and anti-Ro52 antibody-positive hypomyopathic dermatomyositis with interstitial lung involvement showed a marked response to tofacitinib, as evidenced by improved exercise capacity, as well as improvement in skin condition and interstitial lung disease. The treatment was well tolerated [24]. The use of tofacitinib is also discussed for the treatment of refractory anti-NXP2 and anti-TIF1γ dermatomyositis [25].

There is also evidence from case series that the oral PDE-4 inhibitor apremilast may be useful in patients with recurrent DM symptoms as an adjunct to other immunomodulatory medications [26]. In three patients, apremilast 30 mg (2×/d) as an add-on resulted in significant improvement and steroid-sparing effects. The exact mechanism of action of apremilast in DM is not known. Influencing Th1 and Th2 responses are thought to be involved [26].

In addition to abatacept, tofacitinib and apremilast, ustekinumab and cyclophosphamide are among the agents that are used off-label in otherwise refractory courses and are being investigated in ongoing clinical trials.

Congress: Allergy and Immunology Update (SGAI)

Literature:

- Dressler F, Maurer B: Dermatomyositis and juvenile dermatomyositis. Z Rheumatol 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00393-022-01205-5

- Tomaras S, Kekow J, Feist E: Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: updates on diagnosis and classification. Act Rheumatol 2021; 46: 361-372.

- Bottai M, et al: International Myositis Classification Criteria Project consortium, the Euromyositis register and the Juvenile Dermatomyositis Cohort Biomarker Study and Repository (JDRG) (UK and Ireland). EULAR/ACR classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups: a methodology report. RMD Open 2017 Nov 14;3(2): e000507.

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Muskelkranke e.V.: DGM-Handbuch Myositis, 2020, chapter 3a. Dermatomyositis (DM), Prof. Dr. Eugen Feist, Prof. Dr. Cord Sunderkötter. myositispatientguidebook2020web.pdf.

- “Dermatomyositis – Current Diagnostic Approaches and Therapeutic Strategies,” Prof. Britta Maurer, MD, Allergy and Immunology Update (SGAI), Jan. 27-29-23.

- Stuhlmüller B, et al: New aspects on the pathogenesis of myositis. Z Rheumatol 2013; 72: 209-219.

- Schlecht N, et al: Update on dermatomyositis in adults. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2020; 18(9): 995-1013.

- “Myositis Syndromes,” s2k guideline, Commission on Guidelines of the German Neurological Society (ed.), Fully revised: 04/28/2022.

- Okiyama N, Fujimoto M: Cutaneous manifestations of dermatomyositis characterized by myositis-specific autoantibodies. F1000Res 2019 Nov 21; 8: F1000 Faculty Rev-1951. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.20646.1.

- Sell S: Dermatomyositis in multiregional comparison, PhD thesis, Faculty of Medicine, Friedrich Alexander University, Erlangen-Nuremberg, 2021.

- Hill CL, et al: Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet 2001: 357(9250): 96-100.

- Stockton D, Doherty V, Brewster D: Risk of cancer in patients with dermatomyositis or polymyositis, and follow-up implications: a Scottish population-based cohort study. British journal of cancer 2001; 85(1): 41-45.

- Majithia V, Harisdangkul V: Mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept): an alternative therapy for autoimmune inflammatory myopathy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005; 44(3): 386-389.

- Schneider-Gold C HH, Gold R. Mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus: new therapeutic options in neuroimmunological diseases. Muscle Nerve 2006; 34: 284-291.

- Chaudhry V, et al: Mycophenolate mofetil: a safe and promising immunosuppressant in neuromuscular diseases. Neurology 2001; 56(1): 94-96.

- Patil A, et al: Adult and juvenile dermatomyositis treatment. J Cosmet Dermatol 2023; 22(2): 395-401.

- 17 Fiehn C, et al: Rituximab for the treatment of poly-and dermatomyositis: results from the GRAID-2 registry. Z Rheumatol 2018; 77: 40-45.

- Aggarwal R, et al. Efficacy and Safety of IVIg (Octagam 10%) in Patients with Active Dermatomyositis. Results of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase III Trial (ProDERM Study) [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020; 72.

- Dalakas MC, et al: A controlled trial of high-dose intravenous immune globulin infusions as treatment for dermatomyositis. N Engl J Med 1993; 329(27): 1993-2000.

- Stringer E, Feldman BM: Advances in the treatment of juvenile dermatomyositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006; 18(5): 503-506.

- Tjarnlund A, et al: Abatacept in the treatment of adult dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a randomised, phase IIb treatment delayed-start trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 17: 55-62.

- Tang Q, et al. Effect of CTLA4-Ig (abatacept) treatment on T cells and B cells in peripheral blood of patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Scand J Immunol 2019; 89:e12732.

- 23 Wendel S, et al: Successful treatment of extensive calcifications and acute pulmonary involvement in dermatomyositis with the Janus-kinase inhibitor tofacitinib – a report of two cases. J Autoimmun 2019; 100: 131-136.

- Hornig J, et al: Response of dermatomyositis with lung involvement to Janus kinase inhibitor treatment. Z Rheumatol 2018; 77: 952-957.

- Navarro-Navarro I, et al: Treatment of refractory anti-NXP2 and anti-TIF1γ dermatomyositis with tofacitinib. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2020; 19: 443-447.

- Bitar C, et al: Apremilast as a potential treatment for moderate to severe dermatomyositis: a retrospective study of 3 patients. JAAD Case Rep 2019; 5: 191-194.

- Charlton D, et al: Refractory cutaneous dermatomyositis with severe scalp pruritus responsive to apremilast. J Clin Rheumatol 2019; 27:S561-S562.

- 28. Bobirca A, et al: Anti-MDA5 Amyopathic Dermatomyositis – A Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenge. Life 2022; 12(8): 1108. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12081108

- Żychowska M, Reich A: Dermoscopy and Trichoscopy in Dermatomyositis-A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022; 11(2):375. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11020375.

- Drug Information, www.swissmedicinfo.ch/ViewMonographie,(last accessed Mar. 03, 2023).

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2023; 33(2): 47-49 (published 4/20-23, ahead of print).