A systematic approach helps to keep the overview. In benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, patients can often be provided with rapid relief. Targeted reduction maneuvers instead of Brandt-Daroff, if possible. All “peripheral-vestibular” images can be imitated centrally.

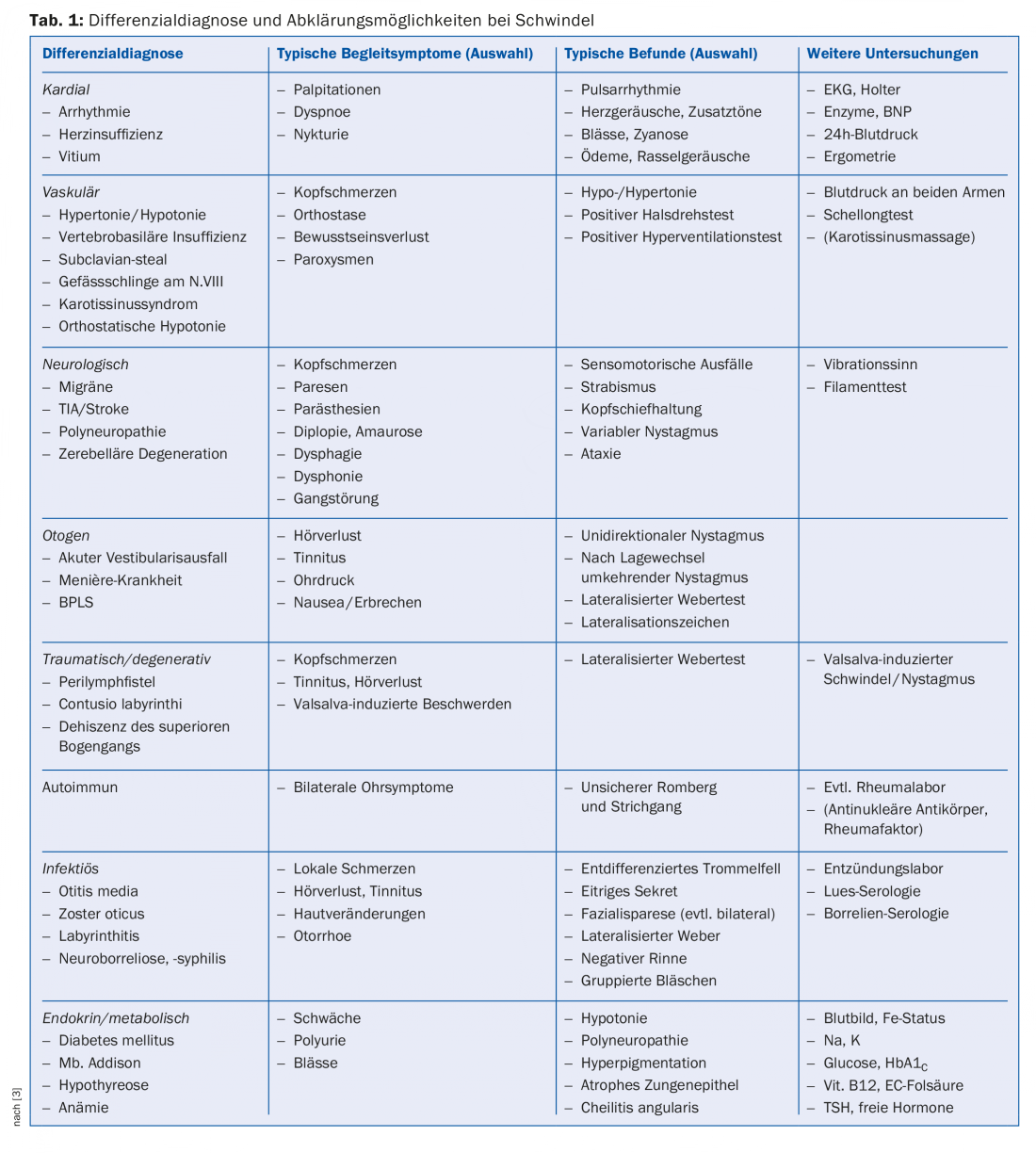

Symptoms of vertigo are often diagnostically challenging. The list of possible differential diagnoses is long and no clear boundary can initially be drawn between some clinical pictures (e.g. between migraine and Meniere’s disease). Others lack clear diagnostic criteria (e.g., cervicogenic vertigo). Often, all that remains at the end of the investigation is a suspicion. This makes a systematic approach all the more important. Efficient primary care physician initial assessment and triage is not only of individual importance, but also of economic importance. Numerous causes of dizziness can be treated purely by primary care physicians without requiring specialized or inpatient services.

What clarifications in the family practice?

Anamnesis: The anamnesis is the main instrument in the diagnosis of vertigo and often enough the only “guide” to the diagnosis. The patients’ experience is the focus here: What exactly do they feel? Is there a component of motion (directional vertigo)? On which plane does it rotate (more horizontal or vertical)? How long do the severe symptoms last (a recent review of possible differential diagnoses depending on duration shows [1])? Are there triggers (exertion, movements, head position changes)? Does the head need to be kept motionless to relieve discomfort? Are there associated cardiac, ear, or neurologic symptoms? Furthermore, cardiovascular risk profile, history of head or body trauma, ocular disease, musculoskeletal disease, and generally preceding similar episodes are important. A symptom diary can make the sometimes difficult differentiation between vestibular migraine and Meniere’s disease possible by documenting numerous episodes.

Status: In addition to the general internal body examination, additional regions are to be included, depending on the complaint profile: Musculoskeletal system, neurostatus, ENT status (ear findings, paranasal sinuses, cervical mobility and muscle tension) with vestibular testing or visual acuity testing. One example: The 18-year-old patient referred for uncharacteristic dizziness showed a subjectively unnoticed cervical lymph node swelling on examination. Further workup revealed Hodgkin’s lymphoma as the cause of dizziness. This underscores the importance of general internist status as the basis of primary evaluation.

Differentiation between central and peripheral vestibular genesis in acute vestibular syndrome is made possible by the three tests grouped under the acronym HINTS (Head Impulse, Nystagmus, Test of Skew) [2]. Thereafter, there are three clues suggestive of a central vestibular cause (primarily stroke): 1. a normal head impulse test (absence of a visible corrective saccade with rapid rotation of the patient’s head 10-20° horizontally and fixation on the examiner’s nose), or 2. a horizontal gaze direction nystagmus (right nystagmus when looking to the right, left nystagmus when looking to the left), or 3. A vertical strabismus (vertical adjustment movements during the alternating cover test).

In Ménière’s disease, acute mixed torsional-horizontal nystagmus is found, initially ipsilesional, directed contralesionally toward the end of the attack, and hearing loss ipsilesional. The transient lateralization signs may be congruent or incongruent with the nystagmus direction. It should also be noted with regard to the vestibular examination that the positioning examination should never be omitted.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPLS) is one of the most commonly overlooked causes of vertigo. Because detectability may be intermittently absent, it is recommended that the positional test be repeated at a second examination time if the history is suggestive. The diagnosis of BPLS can usually be established in highly symptomatic patients without Frenzel glasses (and even with closed eyelids). In some elderly patients, it is recommended to use the Bojrab-Calvert maneuver instead of the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, since the lateral position is perceived as less threatening despite elevation to the shoulder (Fig. 1). In most patients, the ear that is down during the most severe pain is affected, which allows initial therapy selection even without detailed nystagmus observation. In cases of suspected non-organic vertigo, the hyperventilation test (hyperventilating the patient for one minute and then having him describe the symptoms triggered by this) can be helpful. However, hyperventilation can also cause symptoms in organic diseases (in this case usually with corresponding nystagmus), for example in vestibular paroxysmia or vestibular schwannoma.

Further investigations

Table 1 shows more advanced investigations, listed by problem area, that can be performed or arranged in the primary care physician’s office. In subacute situations and in – after clinical findings – cases with suspected intracranial pathology, radiological diagnosis is indicated. With few exceptions, such as in the search for perilymphatic fistulae or dehiscence of the superior arcade, MR examination is preferred. This should include diffusion-weighted images, angiography, post-KM images, and, in the case of vestibular schwannoma, CISS (“constructive interference in steady state”) sequences.

ENT dizziness – how to treat?

Acute peripheral vestibular dysfunction: Acute peripheral vestibular dysfunction (syn. neuritis/neuropathia vestibularis, vestibular failure) may present in different degrees of severity, implying different approaches. In principle, however, organ diagnosis is necessary in all cases because of the possibility of mimicking strokes (even clear HINTS cannot provide 100% certainty). In cases of severe vomiting and inability to walk, inpatient treatment is required; in milder cases, outpatient treatment is possible. Antiemetics and bed rest may be helpful for the first two days of illness, after which gradual mobilization is recommended to achieve optimal compensation in case of persistent peripheral-vestibular deficit. Supportive physical therapy has a high level of evidence regarding subjective outcomes. Steroid therapy is controversial, but there is a slight benefit in favor of recovery of vestibular function based on the randomized-controlled trials that have been performed, which is of high long-term value. However, initial steroid doses of more than 100 mg methylprednisolone/d cannot be justified by the literature. A common regimen for outpatient therapy over 16 days (also called the “Basel regimen” in Northwestern Switzerland) includes:

- Methylprednisolone (Medrol®) 32 mg 3-0-0 for four days, then 2-0-0 for four days, then

- Methylprednisolone (Medrol®) 16 mg 2-0-0 for four days, then 1-0-0 for four days.

Three months after onset, documentation of peripheral recovery is useful, as the majority of this recovery is complete by then.

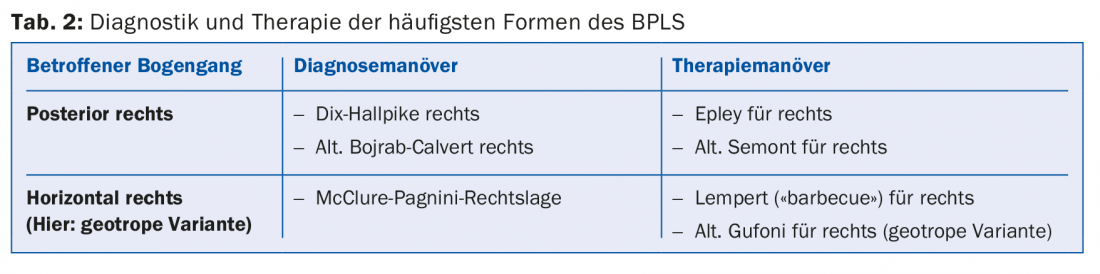

BPLS: BPLS is well known and often successfully treated even by laymen. An overview of diagnostics and therapy is given in table 2.

Ménière’s disease: Ménière’s disease still awaits a satisfactory, non-destructive, yet effective therapeutic option for patients and caregivers. Steroids appear to have some efficacy in transitioning from high to lower disease activity, but larger randomized-controlled trials to support this are lacking to date. If a dose increase of betahistine initially seemed promising, skepticism is again warranted after a new, large-scale dose-finding study [4]. Avoidance of triggers (stress, dehydration, or salt excess) often does not provide a safe benefit. What should not be ignored here, however, is that even longstanding Ménière’s patients can suddenly develop an additional BPLS, which not infrequently plagues them more than the underlying disease and whose reversibility can be perceived as very relieving.

When to refer?

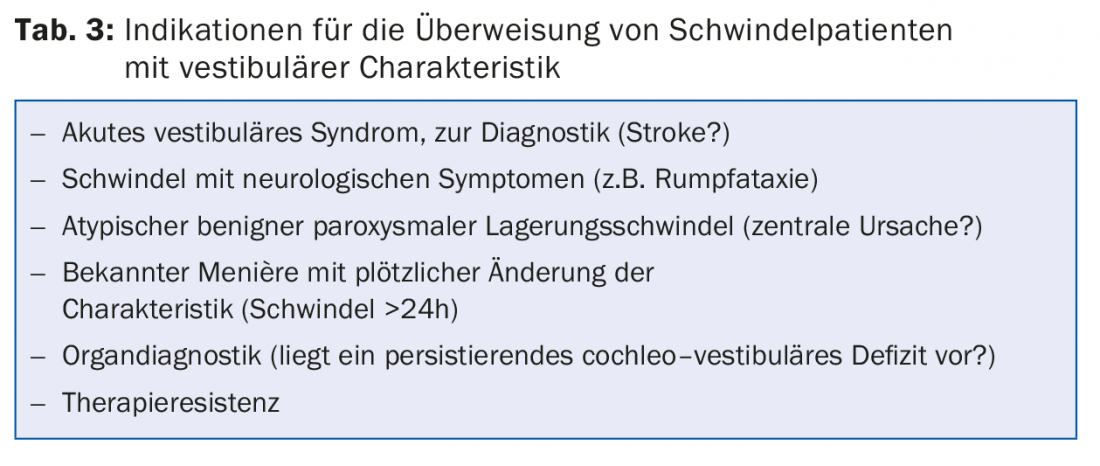

Table 3 shows indications for referring patients with vestibular symptoms. Acute vestibular syndrome (acute vertigo with nausea, nystagmus, and gait disturbance) within the lysis window includes several avertable dangerous courses, so hospitalization is indicated. Even after the lysis window has elapsed, hospitalization is required in these cases if there is even the slightest suspicion of a neurologic cause. Insidiously, central vestibular causes can perfectly mimic peripheral vestibular disease patterns on the one hand, and on the other hand, cerebellar lesions in particular often cannot be detected clinically. Only due to an atypical medium-term course is suspicion then raised and the diagnosis made by MR, or discovered much later by chance.

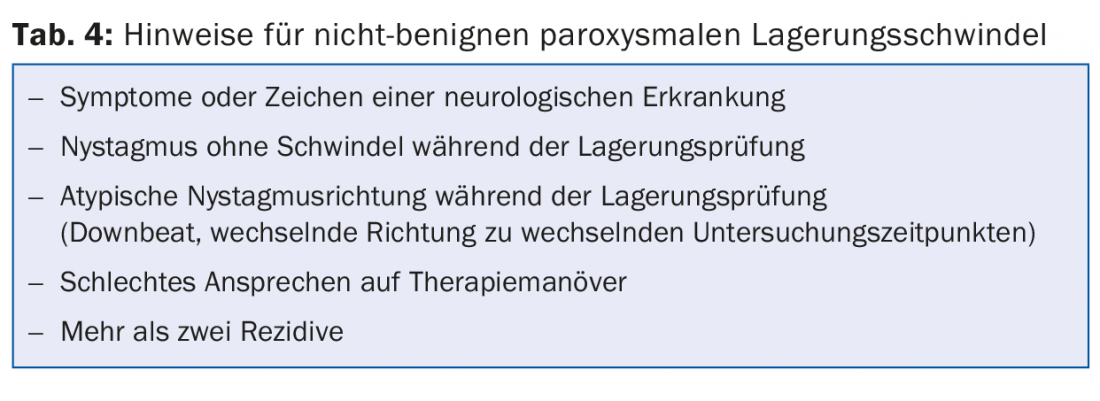

If the examination reveals BPLS and there are reservations about reduction in the office, a prompt referral to an ENT or neurologic colleague is appropriate. However, reservations in BPLS are not always appropriate: targeted, rapid (successful) therapy by the primary care provider forms the ideal case for both patients and primary care physicians. However, if there is no improvement or change in the findings after several reduction maneuvers, critical questioning of the diagnosis is indicated (Table 4), which may then lead to referral.

…and if no cause is found?

A cause that is sometimes controversial and often only detectable by exclusionem is the cervicogenic trigger. Here, a trial of physiotherapy or, depending on the degree of discomfort, a “gentler” approach using osteopathy is warranted. Evidence of nonorganic causes comes from history, abnormal behavior, or sensations during the hyperventilation test.

Phobic vertigo” not infrequently occurs after an organic vestibular disorder and is characterized by second-long, rather undirected sensations of vertigo, especially while standing or walking, often occurring in frightening situations. The exclusion of organic causes is the central element in the management of these patients.

“Multifactorial vertigo” and “age-related vertigo” are other problems that family physicians often face. Even in the absence of a clear diagnosis and in the presence of a chronic condition, vestibular physiotherapy can produce substantial subjective improvements. A symptomatic drug therapy trial with betahistine or cinnagerone can occasionally achieve a positive effect. Ginkgo preparations enjoy good acceptance among patients, although their efficacy for these indications is not sufficiently proven.

Literature:

- Tarnutzer A, et al: Current developments in vertigo diagnostics. Swiss Medical Forum 2016; 16(16): 369-374.

- Zamaro E, et al: “HINTS” in acute vertigo: peripheral or central? Swiss Medical Forum 2016; 16(01): 21-23.

- Miller AJ, et al: Differential diagnosis of dizziness. In: Calhoun KH: Expert Guide to Otolaryngology. American College of Physicians, Philadelphia 2000.

- Adrion C, et al: Efficacy and safety of betahistine treatment in patients with Meniere’s disease: primary results of a long term, multicenter, double blind, randomized, placebo controlled, dose defining trial (BEMED trial). BMJ 2016; 352(01).

- Soto-Varela A, et al: Revised Criteria for Suspicion of non-benign Positional Vertigo. Q J Med 2013; 106: 317-321.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(8): 27-30