When a malignancy is detected in the body, it is often already too late. Despite comprehensive treatment programs, not every tumor at every stage can be effectively treated. Especially in the gastrointestinal tract, changes are often only noticeable at a late stage. However, general screening of the general population is not always effective either. An analysis.

Screening is an examination of asymptomatic individuals without known disease. The aim of this is to detect diseases at an early stage so that they can be treated more effectively. The basis for this must be a certain frequency of illness. The test procedure should also have a high sensitivity and specificity, be cost-efficient and cause little stress to the person concerned, and be safe, explained PD Emanuel Burri, MD, Liestal. Gastrointestinal screening involves the esophagus, liver, gall bladder, stomach, pancreas, and colon. In the esophagus, particular attention must be paid to Barrett’s esophagus. This is because adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction has been steadily increasing since 1975. The increase in incidence is 2.2% per year [1]. The causes are mainly found in obesity, which leads to reflux and ultimately to Barrett’s esophagus.

Endoscopic changes above the gastroesophageal junction from the squamous epithelium to the mucosa of the stomach are referred to as Barrett’s. The squamous epithelium is replaced by a cylindrical epithelium, resulting in intestinal metaplasia. Barrett’s epithelium has a tendency to become dysplastic, promoting the development of adenocarcinoma, the speaker said. The risk in the general population for the occurrence of adenocarcinoma is 0.03%, whereas in patients with barrett’s esophagus it is 0.12%. Is screening worthwhile here? This is supported by the fact that reflux disease is quite common in the normal population with 25-35%. In chronic reflux, the prevalence correlates for barrett esophagus. If this is normally 1-2%, it increases to 7-10% in chronic reflux. However, chronic reflux symptoms are not present in 50% of all patients with Barrett’s esophagus, and 80% of all Barrett’s cancers have not been diagnosed with reflux disease. In addition, 95% of all Barrett’s carcinomas had no known diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus. Burri summarized that many carcinomas are missed because a barrett esophagus diagnosis is not made. However, an argument against screening is that the progression of Barrett’s esophagus to Barrett’s carcinoma is very low. 95% of patients with Barrett’s esophagus do not die from Barrett’s carcinoma.

Screening could be done by gastroscopy. The advantages are the possibility of targeted biopsies, which allows a more accurate diagnosis. However, the high costs as well as quality differences due to different expert opinions in endoscopy speak against this approach. A new method such as cytological analysis by Cytosponge starts here. The cost is lower and it shows good sensitivity (80%) and specificity (87%) [2,3]. All in all, professional societies do not recommend universal screening. This should be reserved for high-risk patients. Male patients over 50 years of age with chronic reflux symptoms, obesity, nicotine abuse, and a family history of barrett’s esophagus are considered high risk.

Gastric cancer mainly in Asian countries

The incidence of gastric cancer varies widely worldwide. It occurs frequently, especially in Asian countries, but rarely in Europe and North America [4,5]. For this reason, screening programs exist only in Asian countries. This is supported by a poor 5-year outcome of 30-40% and the fact that diagnosis often occurs at an advanced stage. Contrasting this is the encouraging trend that the incidence of gastric carcinoma is decreasing, Burri said. In countries where screening is performed, the diagnosis is actually made earlier. As a result, mortality is falling faster than incidence. However, H. pylori eradication is an important factor in decreasing tumor incidence, so a change in strategy to primary prevention is being pursued [6].

Screening of the bile ducts and liver

Among the bile ducts, one disease stands out as requiring screening: primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). It is a chronic, often asymptomatic inflammation of the bile ducts that can lead to cirrhosis through fibrosis. 80% of those affected have comorbid chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Diagnosis is made by imaging [7]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fourth leading cause of carcinoma mortality worldwide. 90% of HCC arise in a cirrhotic liver. The risk of HCC is 3-5% annually, and the 5-year survival rate is 10-15% in the United States [8]. Especially in industrialized countries, the incidence of HCC is increasing. Predominantly due to obesity, metabolic syndrome as well as NASH. Screening should be performed in patients with cirrhosis, hepatitis B, or higher grade fibrosis with additional risk factors, according to the recommendations of the Swiss Association for the Study of the Liver [9].

The lifetime risk of developing pancreatic cancer is 1.6%. An almost perfect test with a sensitivity and specificity of 99% each is available for this. Nevertheless, screening is not performed in the general population because, despite everything, there are 1000 false-positive results per 100 000 people [10]. However, the 5-year survival rate is very poor at 5-10% and the incidence is slightly increasing. In the future, screening may therefore become necessary.

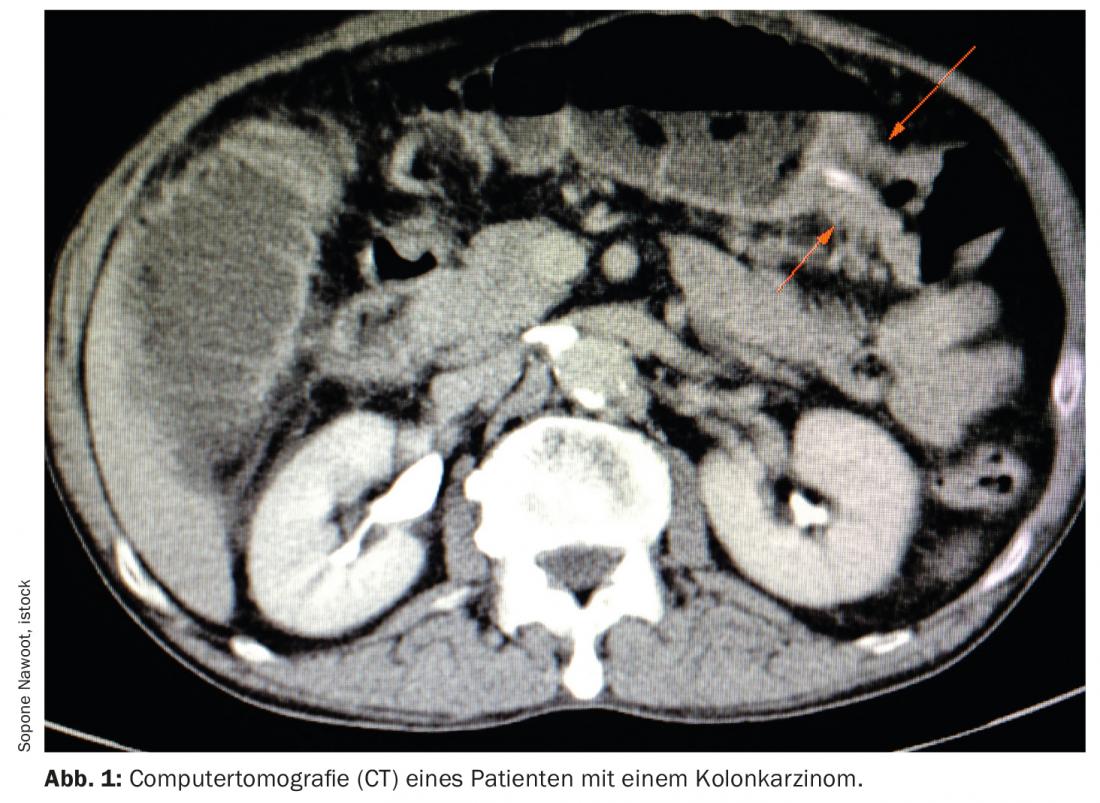

Colon carcinoma: frequent and even more frequent in the future

For colon cancer, the current annual incidence of 50/100,000 is expected to increase by 12.7% in people up to 70 years of age and by 81.4% in patients 70 years of age and older. Because the risk factors, in addition to age, include obesity, nicotine, alcohol and diet. In America, therefore, consideration is being given to lowering the screening age to 45. This is because the advantage of colon carcinoma is its very long lead time before the malignant tumor develops. In Switzerland, screening programs are therefore already being implemented in some cantons. Others want to follow suit. These consist of an FIT, fecal occult blood test every two years, and colonoscopy every ten years.

Source: “Tumor Screening in Gastroenterology,” FomF Update Refresher, Jan. 29, 2022.

Literature:

- Pohl H, Welch HG: The role of overdiagnosis and reclassification in the marked increase of esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence. J Natl Cancer Institute 2005; 97: 142-146.

- Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, O’Donovan M, et al: Cytosponge-trefoil factor 3 versus usual care to identify Barrett’s oesophagus in a primary care setting: a multicentre, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2020; 396: 333-344.

- Ross-Innes CS, Debiram-Beecham I, O’Donovan M, et al: Evaluation of a Minimally Invasive Cell Sampling Device Coupled with Assessment of Trefoil Factor 3 Expression for Diagnosing Barrett’s Esophagus: A Multi-Center Case-Control Study. PLoS Med 2015; 12(1): e1001780.

- Tural D, Selçukbiricik F, Akar E, et al: Gastric cancer: A case study in Turkey. J Cancer Res Ther 2013; 9(4): 644.

- Crew KD, Neugut AI. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(3): 354-362.

- Huang RQ, Li X, Le MH, et al: Natural History and Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk in Untreated Chronic Hepatitis B Patients With Indeterminate Phase. Clin Gastrol Hepatol 2021; S1542-3565(21)00069-0.

- Rizvi S, Eaton JE, Gores GJ: Primary sclerosing cholangitis as a pre-malignant biliary tract disease: surveillance and management. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepathology 2015; 13: 2152-2165.

- Samant H, Amiri HS, Zibari GB: Addressing the worldwide hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, prevention and management. J Gastrointest Oncol 2021; 12(Suppl 2): S361-S373.

- Goossens N, Toso C, Heim MH: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: SASL expert opinion statement. Swiss Med Wkly 2020; 150: w20296.

- Henrikson NB, Bowles EJA, Blasi PR, et al: Screening for pancreatic cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2019; 322(5): 445-454.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2022; 10(2): 30-31.