The sudden cardiac death of an apparently healthy athlete is shocking. Despite low incidence, work is being done on ways to detect SCD early.

Sudden cardiac death (“SCD”) in sports refers to a nontraumatic death that occurs – in individuals without known cardiovascular conditions – during the performance of sports activities or no more than one hour later. It is not uncommon for the event to be preceded by warning signs, for example, heart pain, shortness of breath, or palpitations. If you take such signals seriously, you greatly increase your chances of survival. This was the result of a survey conducted over a period of ten years. Meanwhile, such warning symptoms are being studied in depth [1]. From the point of view of prevention, this rather new finding is of great importance.

How often does sudden cardiac death occur…?

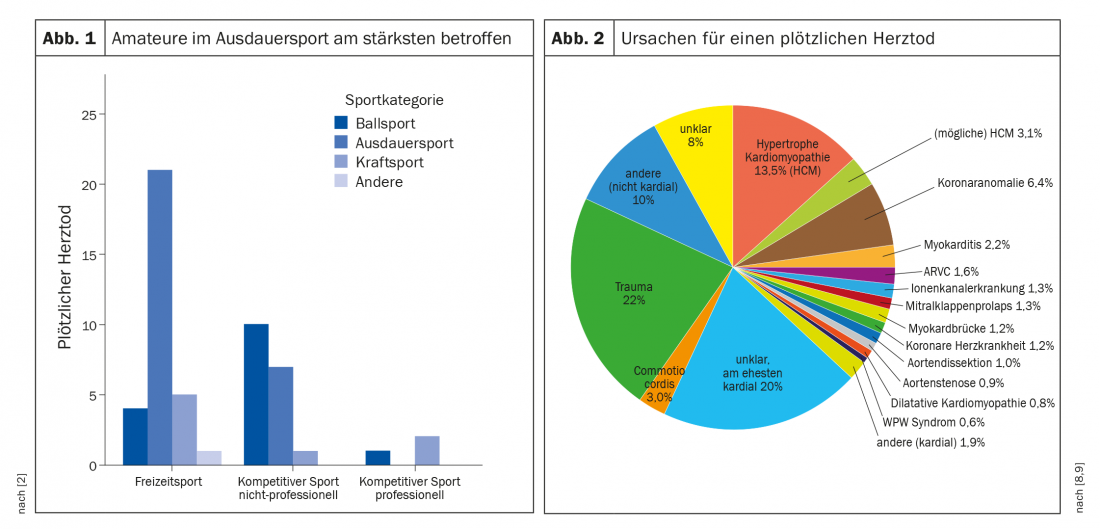

The numbers found in literature regarding incidence vary widely. In Switzerland, where a registry has recently been established to record SCD (“Swiss Registry of Athletic Related Death,” available at www.swissregard.ch), an incidence of 0.21/100,000 athletes per year in recreational sports and 0.57/100,000 athletes per year in competitive sports is referenced. These numbers do not compare with those of African American basketball players, where the incidence is 1/10,000 annually [2]. It must be said, however, that the Swiss data, which cover eleven years, come from autopsies, a measure that is by no means always taken. Considering various sources, the incidence is thus between 0.05 and about 10 per 100,000 sports participants per year, depending on age, gender, ethnicity and sports intensity (Fig. 1) . Overall, the risk may thus be considered low. Thus, the risk of suffering an SCD in sports as a <35-year-old person is three times lower than that of accidental death with a risk factor of 1-3/100,000.

… and why?

Figure 2 provides an overview of the most common causes of SCD. Sudden cardiac deaths due to doping are not included. According to recent studies, SCD is rarely due to structural causes. A Canadian analysis of 74 cases found only two hypertrophic cardiomyopathies, nothing else. It is increasingly believed that primary arrhythmogenic (without a tangible structural correlate) or ischemic causes explain the majority of these deaths. Thus, many cases could not be detected in advance by the currently available screening methods [3]. Such SCD may be hereditary.

Preventing deaths through sports medicine check-ups

Still, there is talk around the world of sports physicals that could prevent at least some SCD. In Switzerland, such check-ups have been practiced for decades, and the Swiss Society of Sports Medicine (SGSM) was one of the first organizations to officially comment on this issue [4]. Such an examination should consist of a focused history, a complete clinical examination, a resting ECG, and, depending on the situation, a blood test. For a long time, there were doubts about the usefulness of ECG examination, but these were dispelled with the formulation of the Seattle criteria and their further refinement [5]. At this point, an interesting British study should be briefly discussed. Between 1996 and 2016, more than 11,000 young soccer players were periodically screened based on the Seattle criteria. Only 7% needed additional investigations due to unclear findings, in one third nothing pathological was found. Changes relevant to SCD were detected in 42 boys (36 times on ECG). During the observation period, 23 players died, eight of them from cardiac causes (two were advised not to play the sport). Six of these eight decedents showed normal values in the examinations.

The study also analyzed the costs and determined so-called “costs per QALYs”: At £1300, this was a rather small amount [6]. An investigation in Switzerland also showed that the price is within a reasonable range [7]. Thus, cost is not an argument for foregoing check-ups.

On a personal note, SCD seems to be a field of cardiology, which is why cardiologists are very active in publishing. However, it would be misguided to limit the sports medical examination to a cardiological one. These check-ups, which are usually recommended annually, should be the occasion for a careful examination of the entire musculoskeletal system, with the trained sports physician playing a central role – also on an educational level. Healthy athletes are not at increased risk of cardiac death, and the overall cardioprotective effects of regular exercise are by no means in doubt. The use of preventive measures, such as informing the athletes about the existence of the problem and a seriously conducted sports medical examination with ECG, can reduce the residual risk again.

Literature:

- Marijon E, et al: Warning Symptoms Are Associated With Survival From Sudden Cardiac Arrest. Ann Intern Med 2016; 164(1); 23-29.

- Gräni C, Trachsel L, Wilhelm M: Sudden cardiac death in young athletes in Switzerland. Forum Med Suisse 2014; 14(35): 642-644.

- Landry CH, et al: Sudden cardiac arrest during participation in competitive sports. N Engl J Med 2017; 377(20): 1943-1953.

- Marti B, et al: Sudden cardiac death in sports: useful screening and preventive measures. Schw Z Sportmed Sporttraumatol 1998; 46(2): 83-85.

- Schindler MJ, Schmied CM: ECG interpretation in athletes – the “Seattle criteria”. Cardiovascular Medicine 2016; 19(3): 72-76.

- Malhotra A, et al: Outcomes of Cardiac Screening in Adolescent Soccer Players. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 524-534.

- Menafoglio A: Morte cardiaca improvvisa del giovane atleta: è possibile prevenirla? Tribuna Medica Ticines 2013; 78: 331-336.

- Maron BJ, et al: Sudden Deaths in Young Competitive Athletes. Analysis of 1866 Deaths in the United States, 1980-2006. Circulation 2009; 119(8): 1085-1092.

- Smith C: Sudden cardiac death in sports. Information brochure from Sportkardiologie.ch. 2014.

- Katz E, et al: Increase of Sudden Cardiac Deaths in Switzerland During the 2002 FIFA World Cup. Int J Cardiol 2006; 107(1): 132-133.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(3): 34-35