The first-line therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with exposure. Pharmacotherapy comes into play when psychotherapy (KVT) does not work adequately or is rejected. The drugs of choice are SSRIs in high doses for at least eight to twelve weeks. Second-line agents are the tricyclic antidepressant clomipramine or the SNRI venlafaxine. In cases of comorbid depression and when obsessive thoughts are prominent, a combination therapy of psychotherapy and medication is indicated. If therapy is resistant to KVT and SSRIs, SSRIs should be increased to the maximum tolerated dose or atypical antipsychotics should be added at low doses as augmentation.

Jean Étienne Dominique Esquirol first described obsessive-compulsive disorder in the modern sense in 1838, calling it the “disease of doubt.” Initial attempts at therapy were initially based on neurosurgical and stereotactic interventions. Later, the disorder, then called “obsessive-compulsive disorder,” was treated psychoanalytically.

Since the introduction of clomipramine for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder [1], later the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and the development of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), obsessive-compulsive disorder is considered to be quite treatable.

Several guidelines exist for both psychotherapeutic and pharmacological treatment of OCD: Nice Guidelines (Review 2011), APA Practice Guidelines (Update 2013), S3 Guidelines of the DGPPN (2015) and the joint treatment recommendations of several Swiss professional societies (SGAD, SGZ, SGBP and SGPP, 2013). The recommendations of the various guidelines are largely consistent. The treatment recommendation of the Swiss Society for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders (SGZ) is discussed in more detail below.

Cognitive behavioral therapy with exposure is considered the first-line treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Pharmacologic treatment is recommended as a second-line therapy, except in cases of severe comorbid depression or dominant obsessive thoughts. Drug therapy should then be carried out in combination with psychotherapy according to the German S3 guidelines. In both acute and longer-term treatment, psychotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder is shown to be superior to psychotropic drug therapy alone [2,3]. An exclusively drug therapy is only recommended if psychotherapeutic treatment options are lacking or if there are very long waiting times for this, if the severity of the symptomatology (e.g. severe depressive symptoms) makes psychotherapy impossible or if the patient does not show sufficient motivation for psychotherapy.

SSRIs as a basic pharmacological treatment

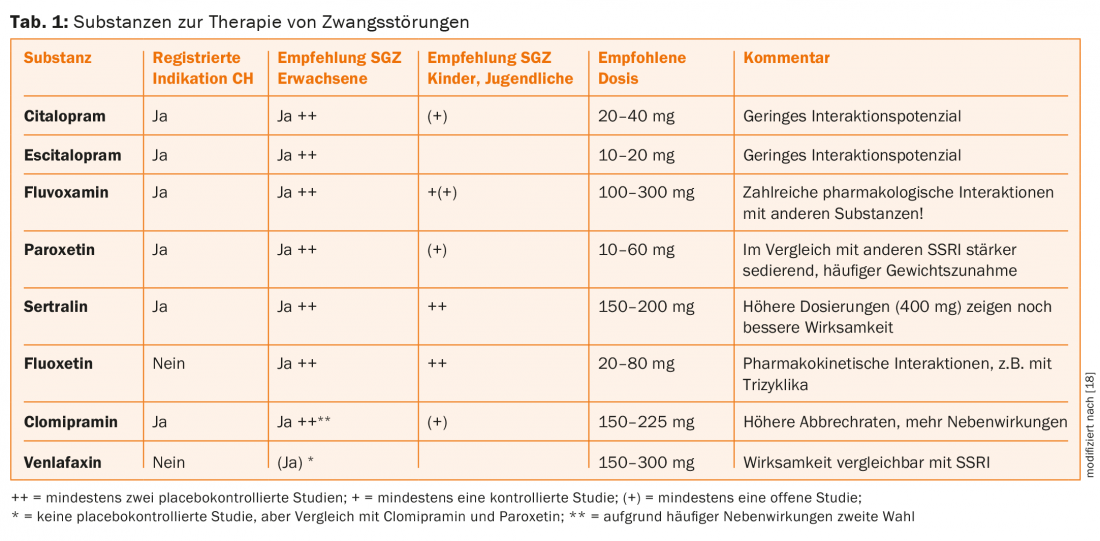

SSRIs in sufficiently high doses are recommended as a basic pharmacological treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Evidence of efficacy is available for the SSRIs as well as for the tricyclic clomipramine [2,4]. Within the class of SSRIs, i.e. between the investigated substances citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and sertraline, no differences in effectiveness can be found, so that the choice of the individual substance is based on the respective side effect profile and spectrum of action (tab. 1) . Clomipramine shows a comparable effect to the SSRIs. Because of the more favorable side effect profile and lower drop-out rate, preference should be given to an SSRI. Because of the high doses of SSRIs commonly used in obsessive-compulsive disorder, side effects must be expected, e.g., increased restlessness, nervousness, sleep disturbances, gastrointestinal complaints, sexual dysfunction. To improve tolerability, the dosage should therefore be administered as slowly as possible up to the maximum tolerated dose.

Medication with an SSRI can result in about a 20 to 40 percent reduction in symptoms after two to three months of treatment. The first improvements appear after four weeks at the earliest. The maximum effect is usually achieved after six to eight weeks. If therapy is successful, the medication should be continued at a constant dosage for one to two years before it can be carefully phased out. Under treatment with an SSRI, patients report an increasing inner distance from compulsions, a decrease in inner tension and depressive feelings. These effects are independent of the duration of OCD and the presence of comorbid depression.

Overall, treatment with an SSRI produces significant improvements in quality of life, psychological well-being, physical condition, social functioning, vitality, and physical symptoms compared with placebo. Improvement in functional capacity correlates with a decrease in obsessive-compulsive symptoms and a subsequent increase in work capacity [5].

After discontinuation of medication with an SSRI, there is a high risk of relapse of 80-90% if psychotherapy was not performed in parallel.

With the exception of clomipramine, tricyclic antidepressants are not effective in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder and should not be used.

Positive results are available for venlafaxine, a selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), from a comparative study with paroxetine [6]. Due to the lack of placebo-controlled trials, venlafaxine is currently recommended only as a second-line therapy for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Data on duloxetine, another SNRI, are not currently available, so no recommendation can be made.

There is also insufficient evidence for mirtazapine as monotherapy, but there is evidence of an earlier response when combined with citalopram [7].

Benzodiazepines are not effective in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder and should not be used, especially since they carry the risk of developing dependence.

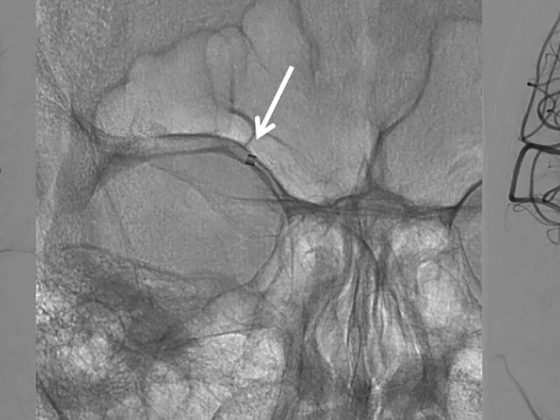

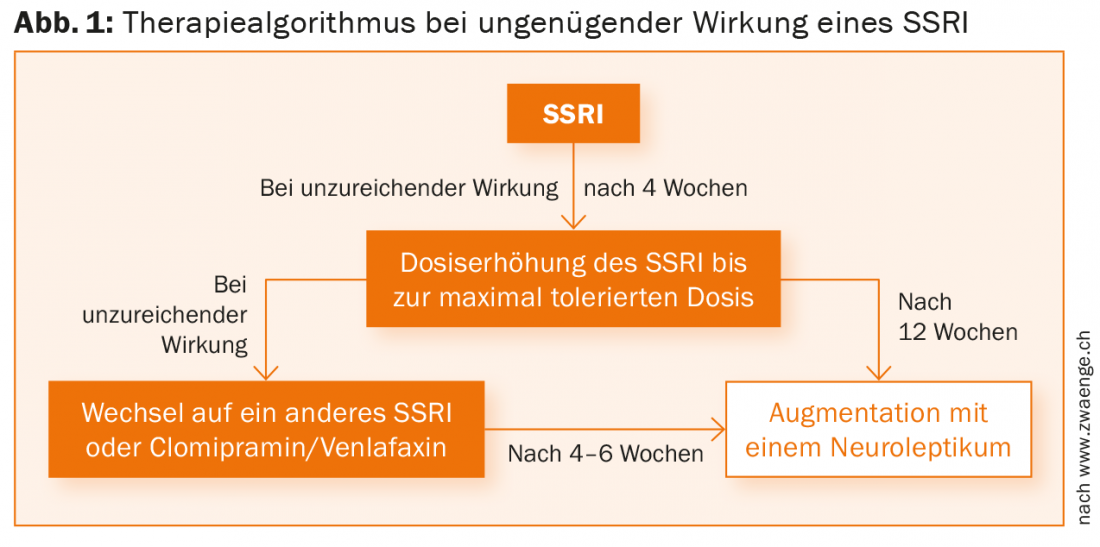

Despite adequate treatment with an SSRI, approximately 20-40% of patients do not respond to treatment. If the effect of an SSRI is absent or inadequate, a dose increase to the maximum tolerated dose is recommended after four weeks. In a second step, a switch to another SSRI, clomipramine or venlafaxine is recommended [2,8]. Another proven strategy is augmentation with an atypical neuroleptic (Fig. 1).

Therapy resistance – augmentation with neuroleptics

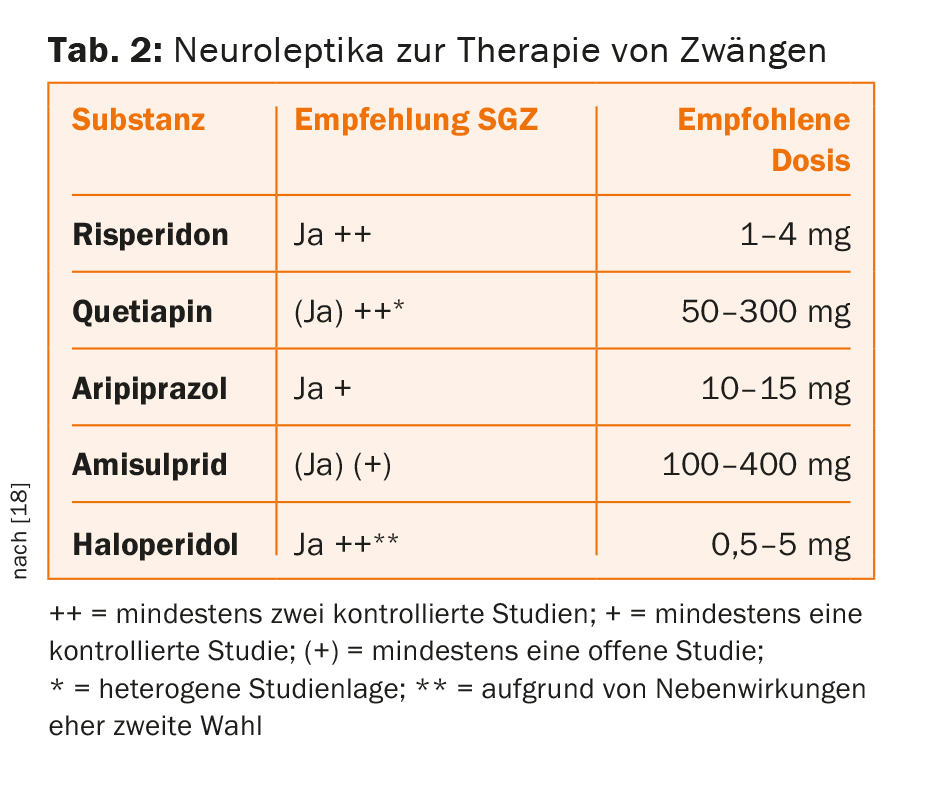

Neuroleptics are not effective in monotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder, but several meta-analyses show significant effects of risperidone, haloperidol, and aripiprazole as an add-on to an SSRI compared with placebo [9–12]. Data on quetiapine are inconsistent and negative on olanzapine. Evidence for the efficacy of amisulpride is currently based on only one open-label study.

An indication for augmentation with neuroleptics is when there is inadequate response to two different SSRIs at sufficiently high doses for an extended period of time, especially when obsessive thoughts dominate the picture, magical fears are mentioned, or tics are present. Comorbid conditions such as bipolar disorder or psychosis may require neuroleptic treatment in their own right. However, it should be noted that neuroleptics, especially clozapine, can induce obsessive-compulsive symptoms in these patients in particular.

Neuroleptics should be used in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorders at the lowest possible dosage (tab. 2) . The effects usually become apparent relatively early, after about one week, with a reduction in obsessive-compulsive symptoms and a decrease in anxiety and depressiveness. If not successful, neuroleptics should be discontinued after six weeks at the latest. Otherwise, augmentation is recommended as a long-term treatment. When discontinuing the medication, it must be phased out over several months.

Combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy

If possible, drug treatment should always be combined with psychotherapy. In a study by Foa et al. a significantly higher response rate (70%) was achieved with a combination treatment of KVT + clomipramine than with medication alone [13]. A follow-up study also found superiority of combination treatment over KVT alone in terms of remission rate [14]. There is strong evidence for the superiority of combination treatment in the presence of moderate depression and the prevalence of obsessive thoughts [2,15]. The benefits of combination treatment can be expected primarily in the first few months, while the differences usually level out in the further course. If there is an inadequate response to pharmacotherapy, further improvement can be expected with the addition of psychotherapy.

Critically, however, combination treatment may adversely affect patients’ self-efficacy expectations when delivering exposure treatment if patients attribute success to the drug rather than to their own abilities. Therefore, both methods should be introduced sequentially.

Outlook for the future

New developments in pharmacotherapy include the use of antiglutamatergic agents such as memantine or riluzole. However, only case reports and small studies of efficacy have been published [16].

Another possibility is found in the substance D-cycloserine, an antibiotic used in the treatment of tuberculosis. This reinforces the effect of fear exposures and learning. Preclinical studies showed an effect on NMDA receptors in the amygdala [17].

Literature:

- Lopez-Ibor Alino JJ, Lopez-Ibor Alino JM: The psychopharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arzneim-forsch/Drug Res 1974; 24: 1119-1122.

- Cuijpers P, et al: The efficacy of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in treating depressive and anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of direct comparisons. World Psychiatry 2013; 12: 137-148.

- Hohagen F, et al: S3-Leitlinie Zwangsstörungen. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Verlag 2015.

- Soomro GM, et al: Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) versus placebo for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008 Jan 23; (1): CD001765. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001765.pub3.

- Hollander E, et al: Quality of life outcomes in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: relationship to treatment response and symptom relapse. J Clin Psychiatry 2010 Jun; 71(6): 784-792. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05911blu. Epub 2010 May 4.

- Denys D, et al: A double blind comparison of venlafaxine and paroxetine in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003 Dec; 23(6): 568-575.

- Pallanti S, Quercioli L, Bruscoli M: Response accelartion with mirtazapine augmentation of citalopram in obsessive-compulsive disorder patients without depression: a pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry 2004 Oct; 65(10): 1394-1399.

- Ipser JC, et al: Pharmacotherapy augmentation strategies in treatment-resistant anxiety disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006 Oct 18; (4): CD005473.

- Bloch MH, et al: A systematic review: antipsychotic augmentation with treatment refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2006 Jul; 11(7): 622-632. epub 2006 Apr 4.

- Dold M, et al: Antipsychotic augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: an update meta-analysis of double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2015; 18(9). pii: pyv047. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyv047.

- Komossa K, et al: Second-generation antipsychotics for obsessive compulsive disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010 Dec 8; (12): CD008141. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008141.pub2.

- Veale D, et al: Atypical antipsychotics augmentation in SSRI treatment refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2014; 14: 31-37.

- Foa EB, et al: Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 151-161.

- Simpson HB, et al: Response versus remission in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2006 Feb; 67(2): 269-276.

- Hohagen F, et al: Combination of behaviour therapy with fluvoxamine in comparison with behaviour therapy and placebo. British J Psychiatry 1998; 173: 71-77.

- Pallanti S, Grassi G, Cantisani A: Emerging drugs to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2014; 19: 67-77.

- Poppe C, Vorderholzer U: Obsessive-compulsive disorders. In: Herpertz S, Caspar F, Lieb K (eds.): Psychotherapy, function- and disorder-oriented approach. Elsevier Publishing, in press.

- Voderholzer U, Hohagen F: Obsessive-compulsive disorder (ICD-10, F4). In: Voderholzer U, Hohagen F (eds.): Therapy of mental illness. State of the Art. Munich: Urban & Fischer 2015.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(6): 20-24.