In a population-based U.S. study, dysphagia affected one in six adult participants. Of these, the vast majority used specific techniques to cope with dysphagia in everyday life. However, only half sought medical attention for dysphagic symptoms. It is not clear from the study data whether treatable etiologies have been missed as a result, but it is clear that the spectrum of causes is broad.

The term “dysphagia” subsumes swallowing disorders of multiple genesis in the area between the lips and the entrance to the stomach. The spectrum of possible causes ranges from cerebral, degenerative, infectious, or malignant diseases to mechanical, traumatic, or functional disorders [1].

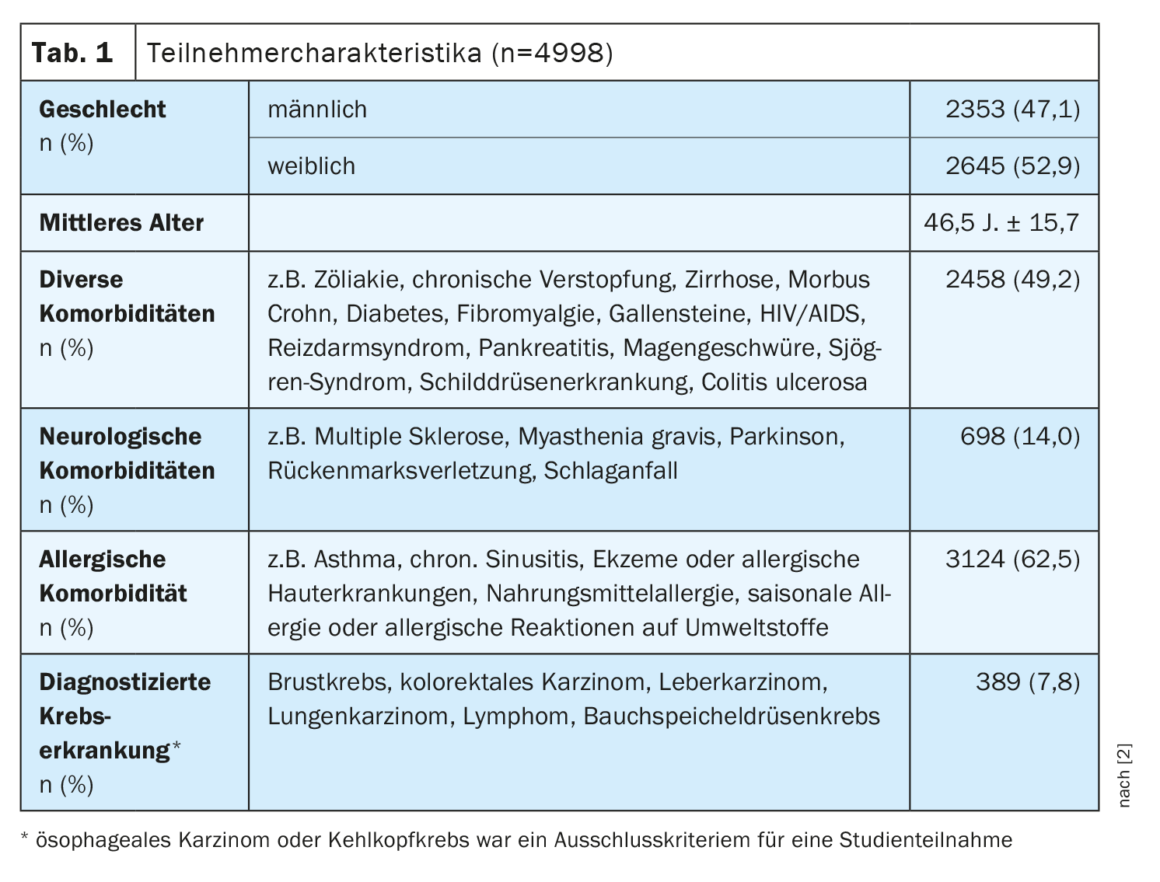

The cross-sectional study by Adkins et al. among others, shows that dysphagia has a high lifetime prevalence [2]. Of 31,129 adults (Table 1) in the United States who participated in an online survey during April 4-19, 2018, 16.1% reported suffering from dysphagia. Of the 4998 dysphagia sufferers, 3362 (67.3%) reported symptom duration of <5 years. In 798 (16.0%), symptoms spanned 6-10 years, and 782 (15.6%) had been affected by dysphagia for ≥11 years.

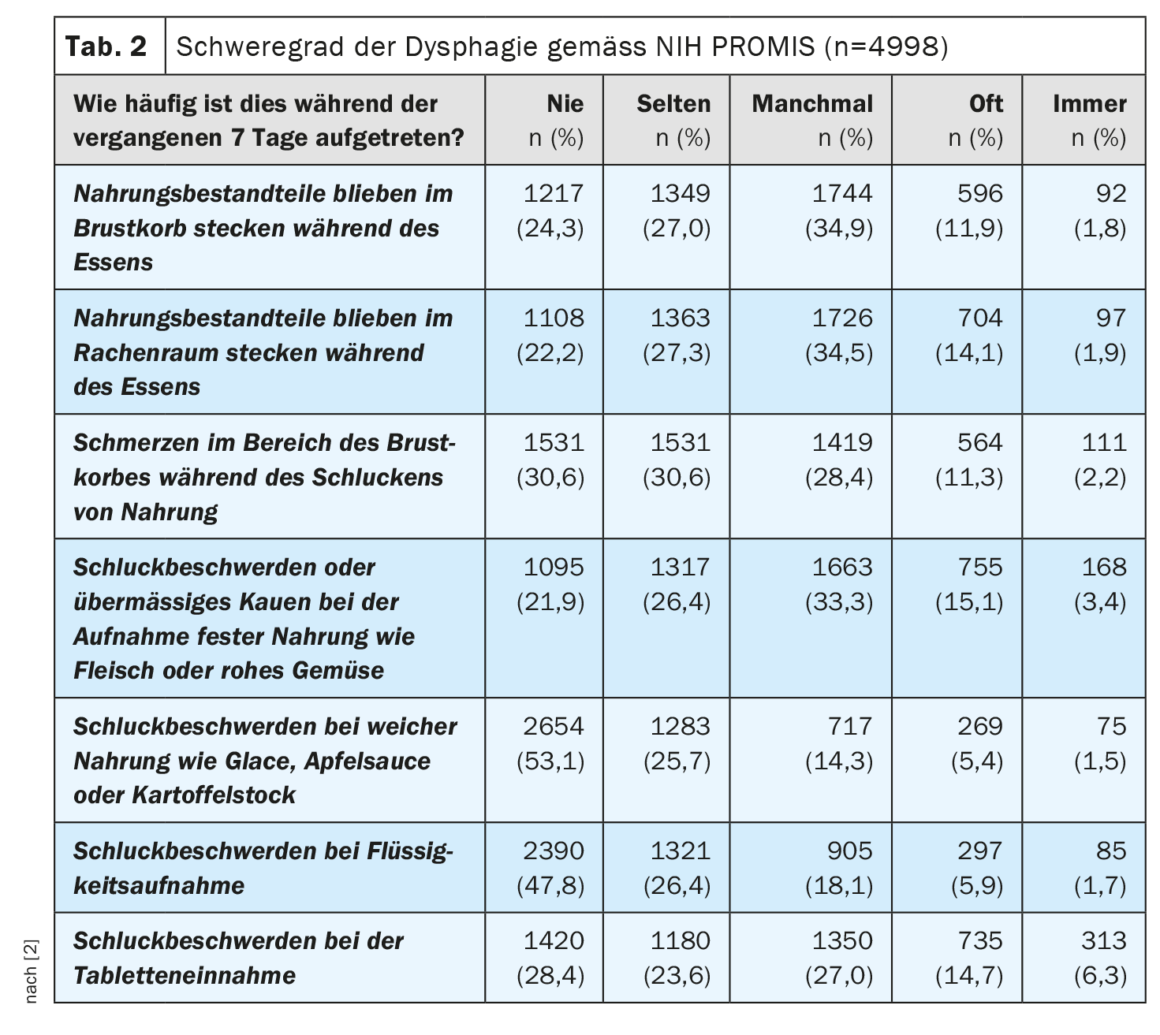

All study participants completed the short version of the PROMIS Global Health (“Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System”) questionnaire [3]. Responses to the dysphagia-related items are shown in Table 2. Of the 16.1% who affirmed dysphagia symptoms, 92.3% had experienced them in the previous week, among others. 16.3% of respondents rated dysphagic symptoms as “fairly” or “very” severe in the past seven days.

Fluid intake (86.0%) and slow meal intake (76.5%) were reported as the most common compensatory measures to alleviate dysphagia [2]. Overall, 51.1% of respondents sought medical attention for their swallowing problems. Older age, male gender, comorbidities, and more severe dysphagia symptoms were associated with a greater likelihood of seeking medical attention (p<0.05). The most common concomitant esophageal diseases were gastroesophageal reflux disease (30.9%), eosinophilic esophagitis (8.0%), and esophageal stricture (4.5%).

Endoscopy rate relatively low

Of the 2553 (51.1%) study participants who sought medical care for their swallowing problems, 1923 (75.3%) consulted a general practitioner, 983 (38.5%) consulted a gastroenterologist, 472 (18.5%) consulted an otolaryngologist, and 320 (12.5%) visited the emergency department [2]. In 1816 (71.1%), the following apparative examinations were performed:

Endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract: 1342 (52.6%)

- Videofluoroscopy of the swallowing act: 744 (29.1%)

- Esophageal swallow: 607 (23.8%)

- Esophageal manometry: 344 (13.5%)

- Imaging techniques: 14 (0.5%)

- Nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy: 2 (0.08%)

The relatively low endoscopy rate in the present study indicates suboptimal use of this diagnostic- and therapy-relevant procedure in everyday practice. The diagnostic utility of endoscopy for dysphagic symptoms includes a study by Varadarajulu et al. clearly. Thus, it was found that swallowing difficulties concealed a serious pathology in 54% of cases and even cancer in 4% [4].

Esophageal dilation was performed in 767 (15.3%) of the dysphagia patients (n=4998) in the present study.

Specifics of subpoulation with eosinophilic esophagitis.

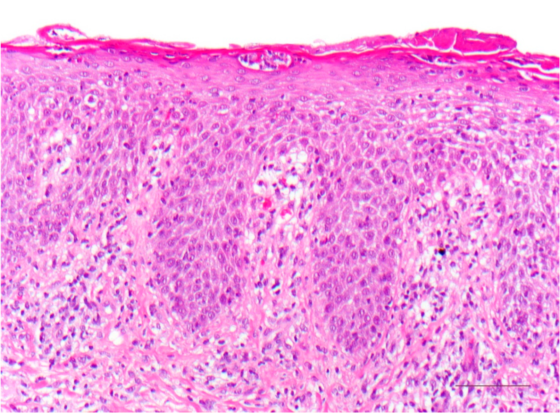

399 (8.0%) of all participants had eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), it was the second most common esophageal comorbidity [2]. Gastroesophageal reflux disease affected 30.9% and esophageal strictures 4.5%. Multivariate analyses revealed that younger age and male sex, among other factors, were associated with a higher likelihood of EoE. In addition, atopic conditions such as asthma, atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, and food allergies were found to be common among EoE sufferers, with 74.4% of this subpopulation suffering from allergic comorbidity. [5].

The vast majority (373; 93.5%) received treatment for their EoE [2].

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs): 216 (54.1%)

- Inhaled steroids: 173 (43.4%)

- Elimination diet: 125 (31.3%)

- Steroid in liquid or suspension form: 105 (26.3%)

- Steroids in tablet form: 86 (21.6%)

- Other treatment options: 4 (1.0%)

Literature:

- Hollenbach M, et al: Dysphagia from a gastroenterologist’s perspective. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2018; 143(09): 660-671.

- Adkins C, et al: Prevalence and Characteristics of Dysphagia Based on a Population-Based Survey. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 18(9): 1970-1979.e2.

- Hays RD, et al: Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res 2009; 18(7): 873-880.

- Varadarajulu S, et al: The yield and the predictors of esophageal pathology when upper endoscopy is used for the initial evaluation of dysphagia. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 61(7): 804-808.

- Gonzalez-Cervera J, et al: Association between atopic manifestations and eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2017; 118(5): 582-590.e2

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(5): 22-24