Cognitive disorders in old age can have many causes that need to be clarified before dementia can be diagnosed. Once these causes have been ruled out, the intensity of the cognitive impairment must be recorded. If this is severe enough to diagnose dementia (vs. mild cognitive impairment), further investigation is needed to determine what type of dementia, vascular or neurodegenerative (viz. Alzheimer’s, Lewy body, or frontotemporal dementia) it is.

Cognitive disorders in old age can have many causes (especially old-age depression, delirium), which must be clarified before dementia can be diagnosed. Once these causes have been ruled out, the intensity of the cognitive impairment must be recorded. If this is severe enough to diagnose dementia (vs. mild cognitive impairment), further investigation is needed to determine what type of dementia, vascular or neurodegenerative (viz. Alzheimer’s, Lewy body, or frontotemporal dementia) it is. Then specific anti-dementia therapy consisting of drug and non-drug measures can be initiated. Starting treatment as early as possible increases the chance for longer-term stability of the patient in his or her familiar environment.

Cognitive disorders and dementia

Dementias are characterized by disturbances in cognitive performance, a reduction in everyday functionality, and the appearance of behavioral and psychological symptoms, so-called secondary symptoms of dementia (BPSD), regardless of the underlying cause of the cognitive disorder. First, therefore, when dementia is suspected, it is important to evaluate the presence and extent of symptoms in these three domains (cognitive impairment, daily functioning, BPSD). In particular, with regard to the development of dementia, it is of great importance to detect a cognitive disorder as early as possible. This is primarily done with a neuropsychological examination, which continues to be considered the gold standard of dementia diagnosis. All memory clinics use the CERAD test battery, which evaluates learning and memory functions as well as other cognitive domains such as visuoconstruction and linguistic functions.

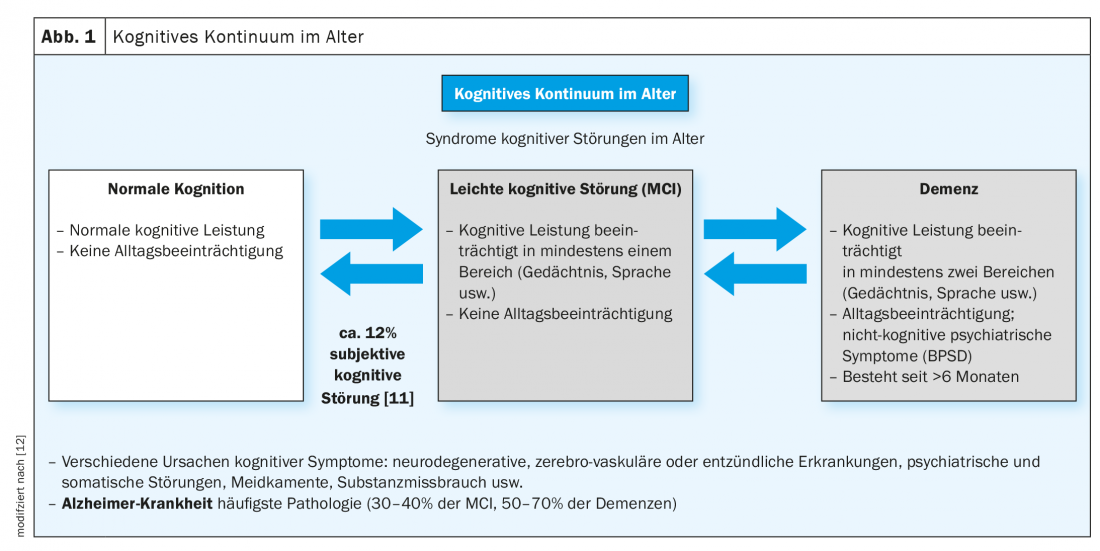

When older people who subjectively report cognitive impairment are examined with the CERAD test battery, there are either unremarkable findings or findings that already indicate significant cognitive impairment but are not accompanied by impairment in everyday life, and significant cognitive decline with impairment in everyday functioning. Only when both areas are significantly affected can one speak of a suspected dementia. If objectively verifiable cognitive impairments are not yet present in everyday life, one speaks of a mild cognitive disorder. Slightly more than half of these patients develop dementia in subsequent years, with approximately 30 to 40% developing Alzheimer’s dementia (Fig. 1) [3,7].

For this reason, it is highly recommended to monitor these patients well in the further course. Independently of the incipient development of dementia, depression and sleep disorders, as well as medication (among various other factors), can also induce the picture of mild cognitive impairment, which is then usually reversible.

In the group of elderly persons with unremarkable cognitive performance in the neuropsychological examination, there are about 12% who nevertheless complain of a disturbance in cognitive performance (often memory and executive functions), i.e., who report a subjective cognitive disturbance [11]. Recently, increased attention has been paid to this group with subjective cognitive impairment, as dementia also developed from this group of individuals later in life. It is possible, among other things, that these are individuals with high intellectual capacity who come from a high baseline level of cognitive reserve and whose relatively reduced cognitive performance is not yet detected by the tests as conspicuous, although the process of progression of cognitive decline has already begun [12].

Diagnostics of dementias

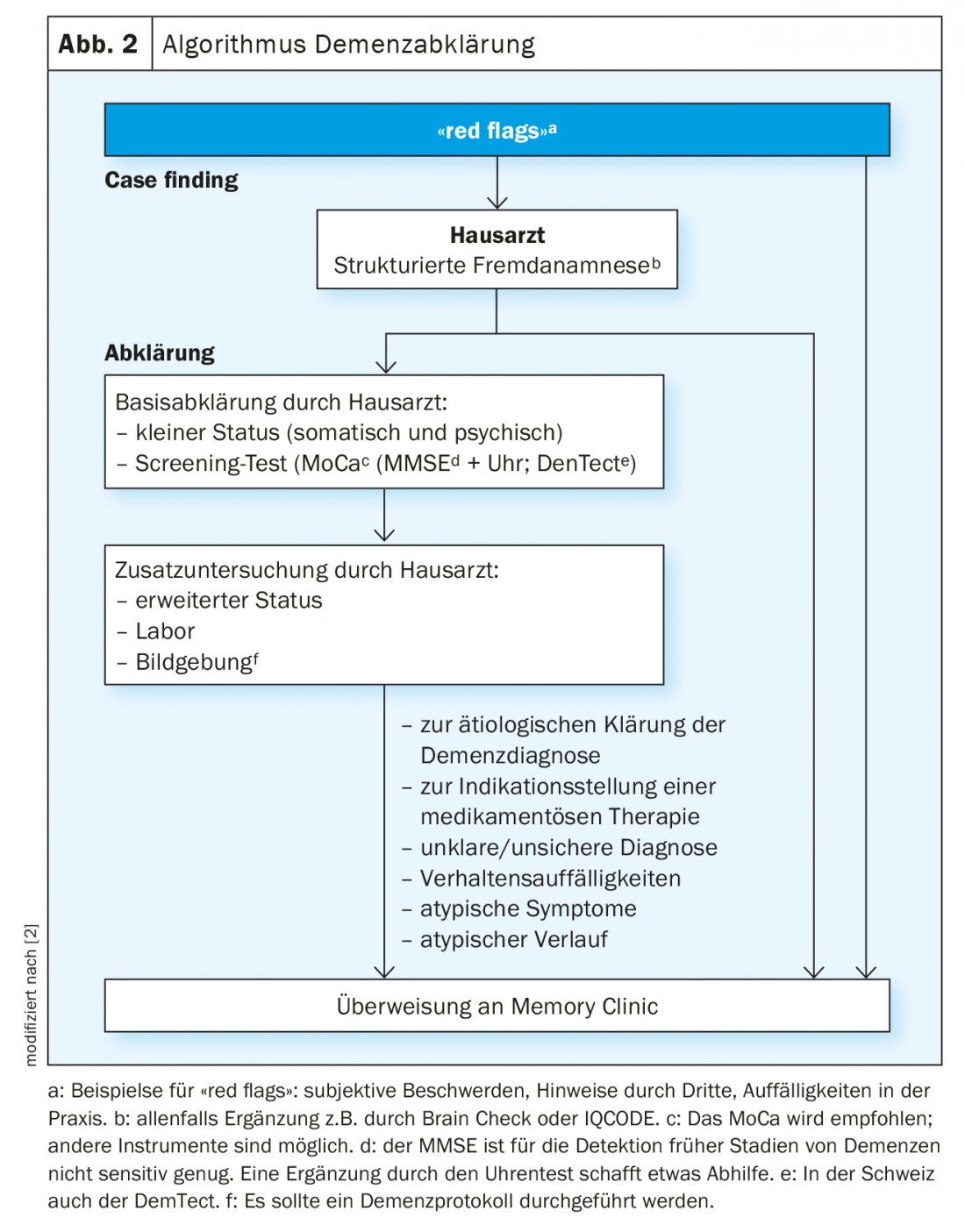

First, it is important to discover individuals with a possible cognitive disorder (case finding). A clue to this is provided by the so-called red flags, both for the relatives or the social environment, as well as for the general practitioners, where patients with incipient dementia often first appear or are discovered. In the family practice, a Mini Mental State Test combined with a clock test or -because of the higher sensitivity- better a Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)-Test should be used as screening procedure and a basic laboratory and if possible a structural imaging should be performed in addition to a detailed medical history and especially a history of others. If there are indications of a cognitive disorder and/or a behavioral disorder on the basis of the red flags, the medical history and the screening examinations, further clarifications should be carried out, preferably in a memory clinic (Fig. 2) [1,2,7].

The current guidelines (S3-Guidelines of the DGPPN, The Recommendations of the Swiss Memory Clinics for the Diagnosis of Dementia) provide precise guidance on the necessary diagnostic investigations and their use when the presence of dementia is suspected [3].

In the Memory Clinic, an in-depth interdisciplinary assessment is then carried out by a specialist (geriatric psychiatrist, geriatrician, neurologist) and neuropsychologist; other specialists trained in geriatric medicine (gerontologist, social counselor, etc.) may be consulted. Specifically, in the memory clinics, an accurate assessment of activities of daily living is performed and indications for more specific examinations such as dementia-related CSF puncture or functional imaging procedures can be made and performed. This in-depth diagnosis in the Memory Clinic enables an exact assessment of the patient’s performance level as well as the possible underlying causes for the detected cognitive disorder in the sense of an exact differential diagnosis.

In the context of the evaluation of the performance level and the recording of further symptoms, in particular BPSD, questions relevant to everyday life can also be discussed, such as fitness to drive, continuation of a possibly still existing occupation or IV-retirement, precautionary order as well as strategies for coping with everyday life.

Acquisition BPSD

For the assessment of BPSD, a characterization/subjective assessment of BPSD by the pa-tient and an external assessment by relatives or caregivers who know the patient well must be performed, as well as an assessment of the BPSD-related burden for the relatives/caregivers. If possible, observation of the behavioral interaction between patient and companion and weighting of the information should be done as part of the diagnostic process. Patient and family should be educated about the discovered BPSD and referral to a specialist (e.g., geriatric psychiatric outpatient clinic, geriatric psychiatric consultation and liaison service) for further treatment of BPSD should be made if necessary [2,5].

Diagnostics and differential diagnostics of dementias

If a cognitive disorder is detected, the main goal of further diagnostics should always be diagnostic clarification with the questions:

- Is dementia present at all?

If so,

- What type of dementia is it?

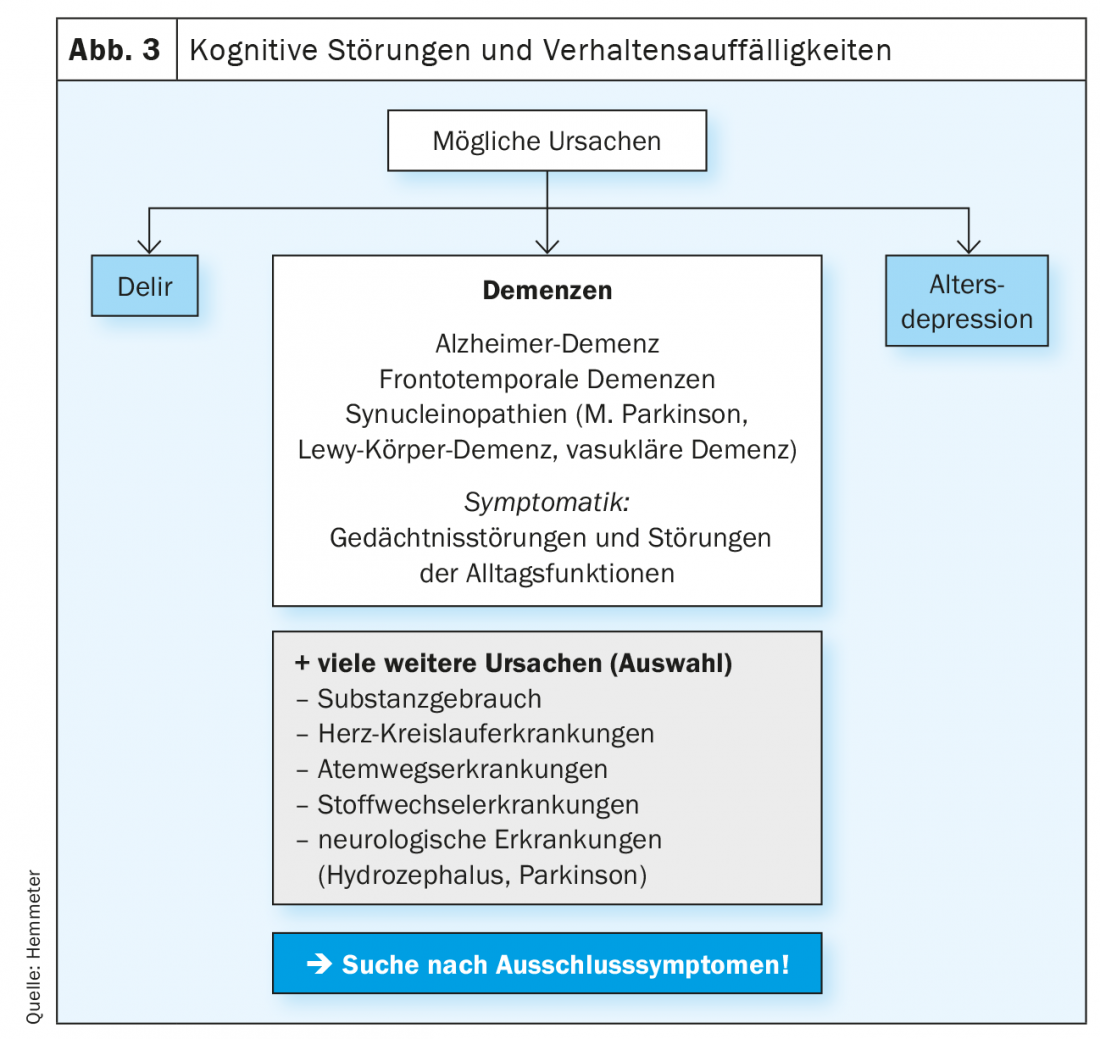

The first step is to clarify whether a cause other than dementia is responsible for the cognitive impairment (Fig. 3).

The most common differential diagnosis to dementia in cognitive impairment in the elderly is geriatric depression, as these patients may also have marked cognitive impairment similar to that of early-stage dementia. On the other hand, the occurrence of a depressive syndrome in old age can also be seen as a psychological symptom (BPSD) of an incipient dementia, in that patients with increasing cognitive disorders find it difficult to orient themselves in everyday life and a social withdrawal with anxious-depressive mood can be the consequence.

Dementia, particularly Alzheimer’s dementia, may also develop in patients with recurrent depressive disorder that has been known for some time, as recurrent depressive disorder is a risk factor for the subsequent development of Alzheimer’s dementia. Often, this diagnostic question cannot be clarified in a cross-sectional setting, but only emerges from a certain course of illness and treatment (antidepressant treatment) [1].

Another important differential diagnosis of dementia is delirium. This question often arises only in the advanced stages of dementia, since, apart from age, the presence of dementia is the greatest risk factor for the development of delirium in old age. Often, however, these patients are not noticed until they experience delirium, as the cognitive impairment and its extent were often not recognized before the onset of delirium. However, delirium can also occur in the early stages of dementia, as well as independently of it, and must then be clarified according to the treatment recommendations for delirium of the SGAP [9].

In addition, there are other somatic causes that can lead to dementia syndromes, so-called secondary dementias. These include, hydrocephalus, cardiovascular and endocrine disorders, inflammation, alcohol and substance use, and also medications that degrade cognitive function. All these (and other possible) causes must be precisely clarified by differential diagnosis.

Once these possible causes have been clarified and old-age depression, delirium and other somatic causes have been ruled out as the reason for the cognitive impairment, the next step is to determine what form of dementia is present. Basically, two different processes come into question for neurodegeneration in dementias, cerebral reduced blood flow leading to vascular dementia or a disturbance of cerebral metabolic processes associated with protein deposition (intra- and/or extracellular) leading to neurodegeneration in terms of neurodegenerative dementias. Of course, both processes can also occur together (as mixed dementia).

These processes are associated with different neuropsychiatric symptoms that need to be clarified as part of the diagnostic process. If there is evidence of neurodegenerative (or mixed) dementia, it must be determined whether the dementia is Alzheimer’s disease, synnucleinopathies (Parkinson’s disease, Lewy body dementia), or frontotemporal dementias (often associated with atypical parkinsonian syndromes) (Fig. 3).

Falls, hallucinations, REM sleep behavior disorder, and increased sensitivity to neuroleptics are clinical indications of Lewy body dementia or Parkinson’s dementia; linguistic abnormalities in the sense of motor or semantic aphasia, as well as behavioral abnormalities, may clinically indicate frontotemporal dementia. This differential-diagnostic clarification is important for the initiation of a specific therapy that is as optimal as possible.

Therapy

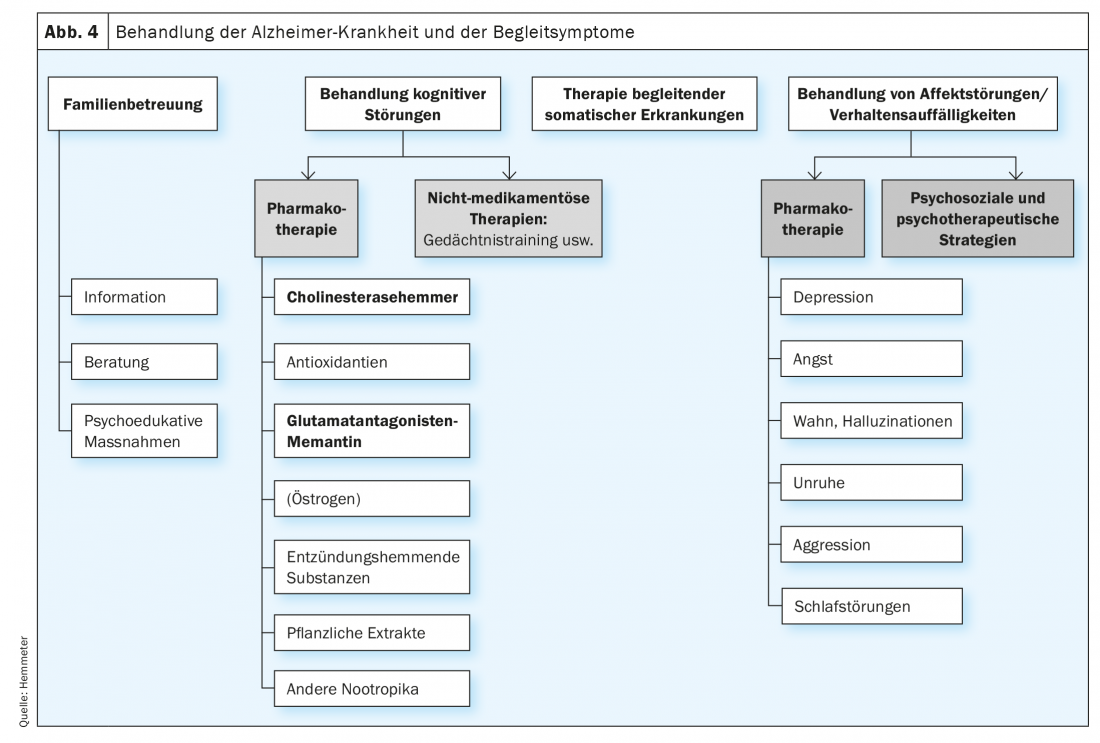

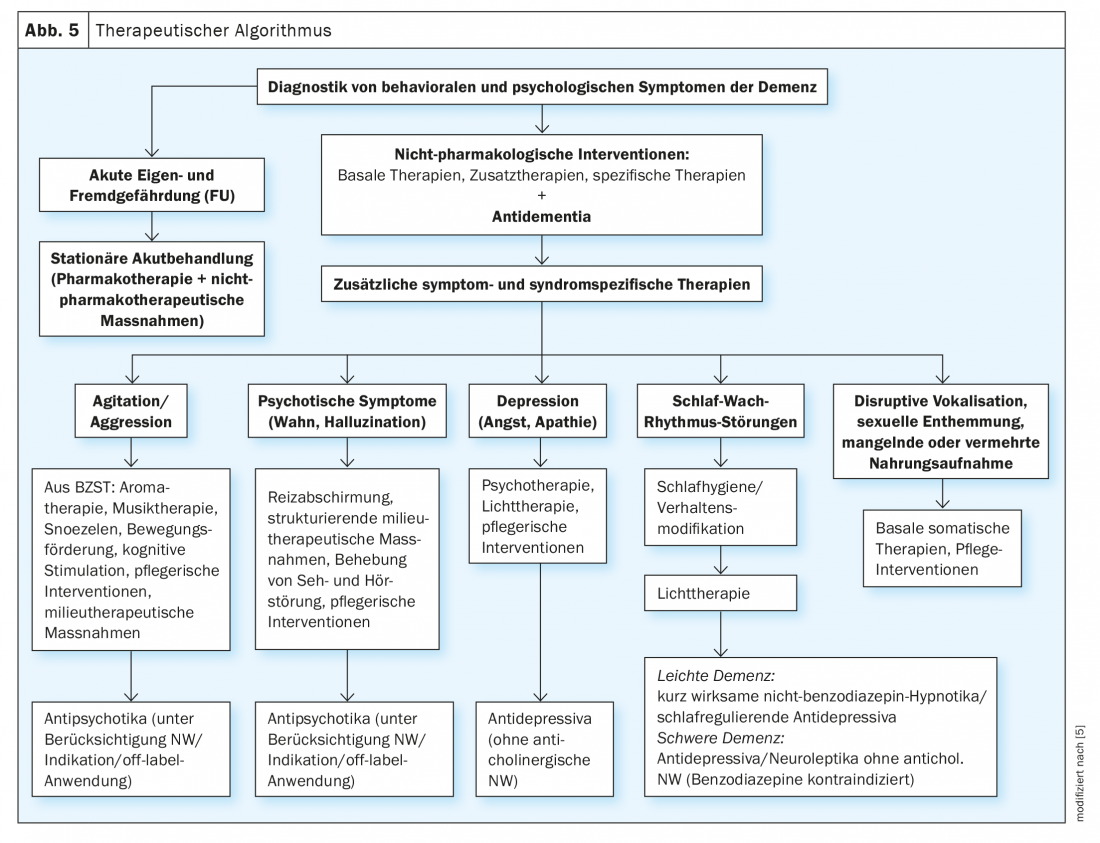

Drug and non-drug therapies are available for the treatment of dementia. A distinction must also be made between therapies that target central cognitive dysfunction and therapies that are used to treat BPSD (Fig. 4). It should be emphasized at this point that drug therapy with anti-dementia drugs is only approved for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, although there is also evidence that patients with Lewy body or Parkinson’s dementia in particular, as well as patients with vascular dementia, may also benefit from the administration of a cholinesterase inhibitor.

Drug therapy options

For the treatment of cognitive impairment in dementia, especially for the indication Alzheimer’s dementia, only four drugs have been approved for many years, three cholinesterase inhibitors (mild and moderate dementia) and the glutamate antagonist memantine (moderate and severe dementia), but these drugs themselves also have positive effects on the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) [4,5].

While choline sterase inhibitors and memantine can (temporarily) halt or delay the progression of cognitive impairment, BPSD can be well treated in many cases. The goal must always be to reduce the symptoms so that these patients can be easily reintegrated into their original environment (at home, in a nursing home).

For the treatment of BPSD, antidepressants and antipsychotics are available, which – in case of diagnosed dementia – should be given together with an antidementive. As a general rule, when using antidepressants and antipsychotics, substances with anticholinergic and extrapyramidal motor effects should be avoided. Attention must also be paid to a possible increase in conduction (QTc time) and hyponatremia (SSRIs), which can lead to states of confusion.

The specific, always cautious use of these substances in BPSD (especially delusions, depression, anxiety, agitation, sleep disturbance) – together with non-drug therapies – can lead to significant improvement and stabilization of patients. However, side effects, as well as comorbidities often present in the elderly, must always be considered, which may limit the use of substances.

Non-drug therapy options

A variety of nonpharmacologic treatment options are now available, especially for the treatment of BPSD; for a review, see Savaskan et al 2014 (Fig. 5) [5]. These can be applied to all forms of dementia, the use depends on the availability, but above all on the individual constellation of the patient, his resources and possibilities. The non-medicinal procedures in particular can lead to improvement of BPSD, they should always be used before drug therapy or at least together with drug therapy.

Of particular importance is stabilization of the circadian day-night rhythm, with constant fixed sleep and wake times, but also fixed times of food intake and activities, which also serve as timers. This behavioral management can be supported by light therapy in the morning (to advance the circadian rhythm if the patient cannot find sleep in the evening) or in the evening (when the pat. is already sleeping early), so that sleep pressure is used up in the middle of the night.

Physical activity in the form of walking or even toning and balance exercises do not lead to an improvement in cognition per se, but they can lead to an improvement in BPSD and especially to a stabilization of the circadian rhythm [8,10].

Mild and subjective cognitive impairment – treatment options.

Since patients with mild cognitive impairment do not yet have any limitations in daily life, there is no indication for drug therapy. Therefore, mainly non-drug therapies can be applied here, such as memory training, physical activity, sleep regulation as well as training of everyday activities (skills). However, it should be remembered that mild cognitive impairment may conceal the onset of dementia as well as other diseases (somatic and psychological, e.g. depression), these patients should be seen and managed by a physician and their progress monitored. A drug option at this stage may be the administration of Ginkgo biloba, which has no indication for use in dementia, but indications exist from individual studies that cognitive performance as well as behavioral disorders can be improved. The same applies to subjective cognitive impairment, in which at least in individual cases an incipient progressive dementia development may be present.

Prevention

Influenceable and non-influenceable risk factors are found for dementias. Age, a positive family history, female gender and other genetic factors such as apolipoprotein E cannot be influenced. Many risk factors, on the other hand, can be influenced and can thus serve as an approach for prevention. These include alcohol and nicotine use, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and obesity, as well as low education and low cognitive and physical activity (not a complete list).

Thus, abstinence from alcohol and nicotine, cognitive activity into old age, and especially physical activity and exercise, which can also reduce cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors, are important elements that can be used to reduce the risk of later dementia [6].

Take-Home Messages

- Cognitive disorders can have many underlying causes, involving both mental and physical illnesses. Therefore, a broad differential diagnosis is of great relevance .

- Mild cognitive impairment, as well as subjective cognitive impairment, can develop progressively into dementia. These patients should be well investigated and the course followed up.

- The most common differential diagnoses of dementia are geriatric depression and delirium.

- The basic diagnosis of dementia can be done in the family doctor’s office, further examinations for differential diagnosis, especially which type of dementia is present, should be done in a memory clinic.

- Drug and non-drug therapies are available for the treatment of dementia, which can positively influence BPSD in particular, but also delay the progression of neurodegenerative dementia.

- Physical and mental activity into older age can reduce modifiable risk factors of dementia (such as type II diabetes and cardiovascular disease).

Literature:

- Hatzinger M, Hemmeter U, Hirsbrunner T, et al: Recommendations for diagnosis and therapy of depression in old age. Praxis (Bern 1994). 2018 Jan;107(3): 127-144.

- Bürge M, Bieri G, Brühlmeier M, et al: Swiss Memory Clinics’ recommendations for the diagnosis of dementia Praxis 2018; 107(8): 435-451.

- S3 Guideline Dementia – Long Version, DGPPN 2016. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/038-013l_S3-Demenzen-2016-07.pdf

- Frisoni G, Annoni JM, Becker St: Position Statement on Anti-Dementia Medication for Alzheimer’s Disease by Swiss Stakeholders. Clin Transl Neurosci 2021; 5: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ctn5020014

- Savaskan E, Bopp-Kistler I, Buerge M, et al: Recommendations for diagnosis and therapy of behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia (BPSD)]. Praxis, 2014; 103(3).

- Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, et al: Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol 2014;13(8): 788-794

- Hemmeter U, Strnad J, Decrey-Wick H: Further development of recommendations in the areas of early detection, diagnosis and treatment for primary care, subproject 6.1. of the National Dementia Strategy, BAG, Link: www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/themen/strategien-politik/nationale-gesundheitsstrategien/nationale-demenzstrategie.html

- Hoffmann K, et al: Aerobic exercise in Alzheimer’s disease, Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2016; 50: 443-453.

- Savaskan E, Baumgartner M, Georgescu D, Hafner M, Hasemann W, Kressig RW, Popp J, Rohrbach E, Schmid R, Verloo H.: Recommendations for prevention, diagnosis and therapy of delirium in old age. Praxis (Bern 1994). 2016 Aug; 105(16): 941-952.

- Hemmeter UM, Ngamsri T: Physical Activity and Mental Health in the Elderly. Praxis (Bern 1994): 2022; 110(4): 193-198.

- Subjective cognitive decline d A public health issue. Available at: www.cdc.gov/aging/agingdata/docs/subjective-cognitive-decline-508.pdf. Accessed August 3, 2020

- Mistridis P, Mata J, Neuner-Jehle S, et al: Use it or lose it! Cognitive activity as a protective factor for cognitive decline associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017 Mar 1; 147: w14407.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2022; 20(6): 8-13.