The clinical presentation of viral hemorrhagic fever (VHF) is mostly nonspecific (flu-like syndrome) and difficult to distinguish from other common infectious diseases. For risk assessment, the case definition of the different VCFs is a necessary tool to identify these diseases. Travel history is central to including or discarding VCF in the differential diagnosis. Prompt contact with the cantonal medical office or infectious disease reference center is essential for optimal management of suspected person-to-person VCF. Personal protective equipment (PPE) is required for any patient contact with a suspected case, with the goal of providing maximum skin and mucosal coverage.

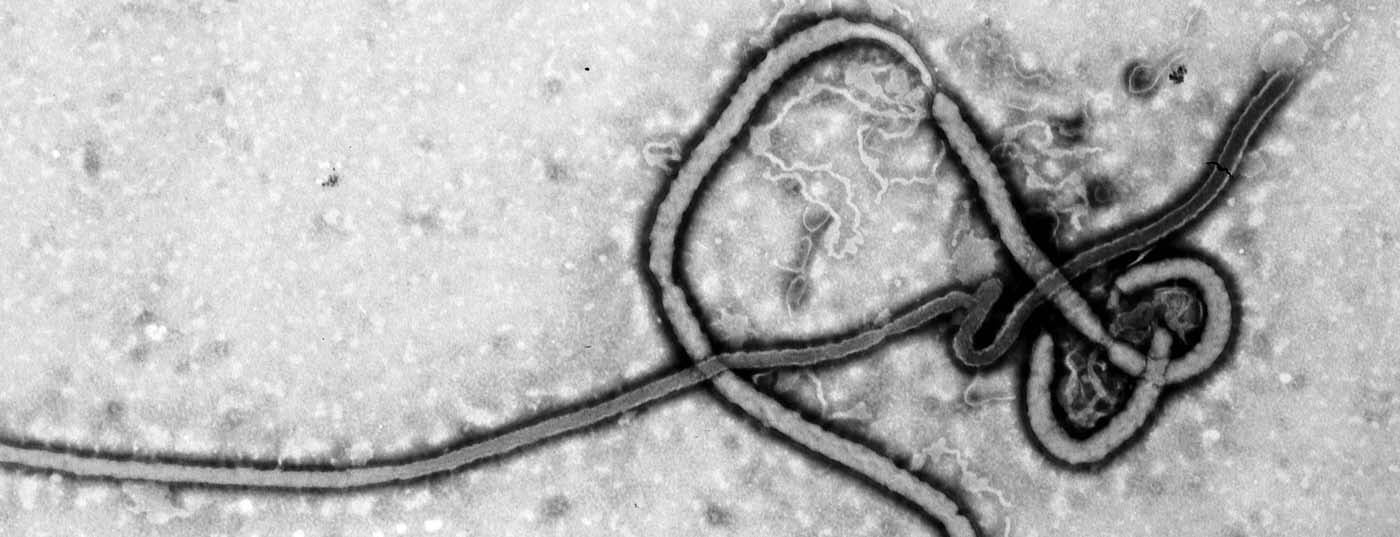

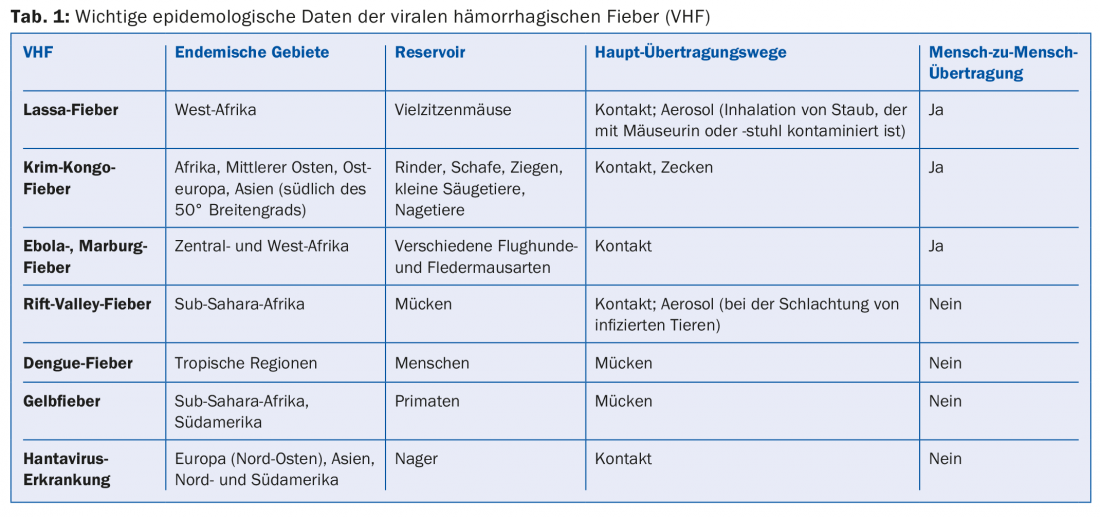

The term viral hemorrhagic fever (VHF) includes the common clinical picture of various diseases caused by viruses. These include the Filoviridae (Ebola fever, Marburg fever), Arenavirus (Lassa fever), Bunyaviridae (Crimean-Congo fever, Rift Valley fever, Hantavirus disease), and Flaviviridae (yellow fever, dengue fever). Apart from the dengue virus, all viruses originate in animals, and the corresponding disease patterns therefore belong to the group of zoonoses. Arthropods are partly responsible for transmission, for example mosquitoes (yellow fever virus, dengue virus, Rift Valley virus) and ticks (Crimean-Congo virus). However, transmission is much more common through direct contact with infected humans or animals: through contact with body fluids (blood, urine, vomit, saliva, diarrhea), via mucous membranes, injured skin, or through percutaneous exposure.

Particularly dangerous to humans are those VCFs in which human-to-human transmission is possible (Ebola fever, Marburg fever, Lassa fever, Crimean-Congo fever). Only in Lassa and Rift Valley fevers have aerosol transmissions been described. Currently, there is no evidence that transmissions of other VCFs occur via droplets or aerosols. VCFs occur worldwide and depend on the ecology of the reservoir or vector (Table 1); however, they are mainly endemic to Asia (dengue fever, Crimean-Congo fever) and sub-Saharan Africa (Ebola, Marburg, Lassa fevers). Hantaviruses are common worldwide, and a major outbreak occurred in Germany between 2011 and 2012 [1].

Ebola outbreak in West Africa: update

Since the beginning of the Ebola epidemic in West Africa in December 2013, a total of 25178 cases (including confirmed, probable, and suspected cases), including 10,445 deaths, had been reported to WHO by early April 2015 [2]. In Liberia, the epidemic is currently under control, and the last patient with confirmed Ebola fever died on March 27, 2015. In Sierra Leone, the trend is sharply downward, while in Guinea new cases continue to be reported in various regions.

Clinical image

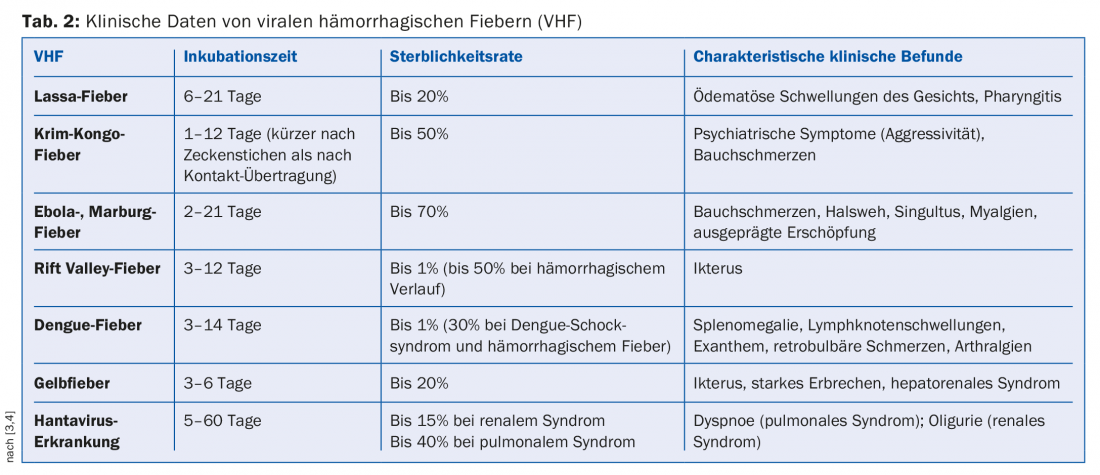

In general, the clinical picture in VCFs begins after an incubation period of about 1-2 weeks with sudden fever and malaise, followed by flu-like, nonspecific symptoms (Table 2) .

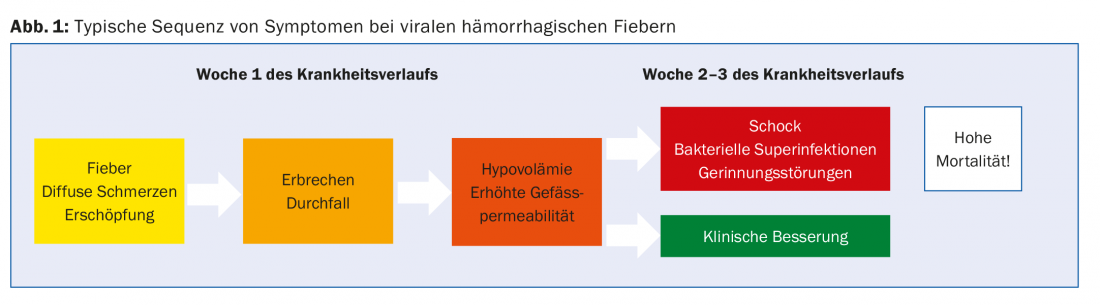

The incubation period is shorter for Crimean-Congo fever, Ebola fever, and Marburg fever, and longer for Lassa fever [3,4]. Particularly in Ebola, pronounced fatigue and severe myalgias are already discrepant to the other nonspecific symptoms at the onset of the disease. In the later course (usually from week 2), abdominal pain, vomiting and sometimes profuse diarrhea follow (Fig. 1). At the beginning of a local outbreak, cholera, abdominal typhus or malaria are usually suspected on the basis of these symptoms.

Pathophysiologically, these symptoms are based on a strong elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines with secondary vasodilation and increased vascular permeability. This can lead to severe fluid shifts into the third space and coagulopathy with development of end-stage hypovolemic shock [5]. Hemorrhagic phenomena probably occur less frequently as a complication and cause of death than previously thought and might be assumed from the name. This has been demonstrated by the current Ebola epidemic in West Africa [6]. In this epidemic, bacterial superinfections (probably in the context of translocation in the intestine) often determine the course in critically ill patients. In hanta fever, two syndromes occur in different geographic regions. The Eurasian form dominantly develops renal failure, and the American form develops pulmonary failure.

Viral hemorrhagic fevers in practice.

The likelihood of diagnosing VCF in a family practice in Switzerland is very low; except for dengue fever, these infectious diseases are very rarely found in travelers returning to Switzerland [7,8]. The overall risk to travelers is estimated to be less than one case per million travelers returning from endemic African countries. Lassa fever has been diagnosed in only 28 travelers in the last 30 years, and dengue fever in approximately 20 of over 1000 ill travelers [9]. According to the FOPH, three cases of human-to-human transmissible VCF were diagnosed in Switzerland from 1994-2008 [10]. The fourth patient in the meantime was the doctor treated in Geneva who had contracted Ebola fever in Sierra Leone at the end of 2014. Overall, during the current Ebola epidemic, only one of the known patients treated in a Western country is considered a traveler. This was a patient who had flown asymptomatically from Liberia to Dallas, USA, and then developed symptoms there – five days after his return – that were not initially recognized as Ebola [11]. All other Ebola patients treated in Europe or North America were aid workers.

The example of the Dallas patient exemplifies the difficulty of quickly recognizing a suspected case based on the initial nonspecific symptoms; thus, the patient in question was treated twice in an emergency department before Ebola was first suspected. In principle, however, even during an existing VHF epidemic, a tropical returnee is more likely to suffer from one of the much more common and treatable infections, such as malaria, traveler’s diarrhea, or influenza.

Important information for risk assessment

In addition to recording symptoms, travel history is central to including or discarding VCF in the differential diagnosis [12]. The exact travel area, length of stay, and contacts with sick or deceased people and animals should be inquired about. The most important information on outbreak updates is published by WHO Disease Outbreak News (www.who.int/topics/haemorrhagic_fevers_viral/en), or you can get information on travel medicine websites such as Safetravel (www.safetravel.ch) or Tropimed (www.tropimed.com). The case definition of the major VCFs is noted on all national or international health agency websites [13]. It should be noted, however, that the clinical criteria of the case definitions are by their nature very broad and are accordingly met in virtually all febrile travelers returning from endemic areas. In case of the slightest suspicion, the attending physician should immediately contact the cantonal medical office and/or the infectiological reference center. Additional clinical examinations such as laboratory and X-ray diagnostics or transfer to hospital should only take place after consultation.

Because of the potential for infection on clinical examination, a patient with a high suspicion of VCF must be treated primarily as if it might be a form with human-to-human transmission. Any further investigations should be performed in a dedicated reference center under strict isolation measures. Laboratory analyses are performed exclusively in a level 4 biosafety laboratory. In Switzerland, this is the reference laboratory at the National Center for Emerging Viral Diseases (NAVI) at the University Hospital of Geneva.

Recommendation for the procedure in patients with suspected VCF in the family practice.

To reduce the risk of infection in a suspected case of person-to-person transmissible VCF, special hygiene measures are necessary. First, the patient is isolated in a separate room. Any physical contact with the patient should be avoided, and a single person is delegated to interact with the patient [14]. This person should wear at least one pair of gloves and, if available, a surgical mask, goggles and over-apron. To reduce the risk of infection, hand disinfection after each patient contact and disinfection of areas exposed to body fluids are important protective measures. Prompt contact with the cantonal medical office or infectious disease reference center is essential for optimal management of a suspected case of person-to-person VCF. If the FOPH case definition (using Ebola as an example) is met, the staff at the receiving center hospital will receive the patient – after appropriate preparation of the isolation room – with special protective equipment. This consists of either gloves, over apron, TB mask and goggles or a liquid tight coverall combined with respirator.

Recommendations for travelers going to a possible Ebola epidemic area

The current risk to travelers to West Africa who do not have direct contact with ill or deceased humans or animals is considered very low. Throughout the current epidemic, no travel restrictions have been imposed by the FOPH, the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA), or the WHO. However, local exit or travel bans were repeatedly imposed within the affected countries. Travelers must inform themselves accordingly on site about the currently valid measures and instructions of the local authorities. Specific behavioral recommendations for travelers to Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea are [15,16]:

- Do not come into contact with diseased persons or wild animals (especially monkeys, bats/flea dogs) or their excreta.

- Explicitly, sexual intercourse with cured persons should be avoided until three months after recovery from Ebola infection. The most recent patient to contract Ebola in Liberia is believed to have been sexually transmitted; her husband had been discharged from an Ebola treatment center a few weeks earlier. No others with Ebola were found despite intensive environmental reconnaissance.

- Avoid consumption of game meat.

Outside of a classical epidemic, persons with potential contact with vectors or reservoir animals are generally at risk of contracting VCF (e.g., during camping vacations, persons with long-term stays in endemic countries, geologists, researchers). Accordingly, standard hygienic measures incl. Mosquito and tick protection to be explained.

To date, there are no vaccines or drug prophylactics or commercially available therapies. Currently, however, one of the vaccine candidates is being tested in initial field trials in Guinea. Phase I and II studies had demonstrated good immunogenicity [17], thus confirming the good results of animal studies (100% protection against provocation infection with Ebola virus in primates). The only effective prevention therefore lies in rigorous hand hygiene and – in the case of contact with a known positive source – in the application of strict protective measures. Further outbreaks with VHF are to be expected. It is hoped that important lessons have been learned from the current outbreak and thus appropriate protective measures can be implemented more quickly and effectively in the future.

The authors would like to thank the specialist team of hospital hygiene at Inselspital Bern and Dr. Daniel Koch, FOPH, Infectious Diseases Section, for their critical review of this article.

Literature:

- Boone I, et al: Rise in the number of notified human hantavirus infections since October 2011 in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. Euro Surveill 2012; 17(21).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Ebola Situation Report. April 1, 2015 (http://apps.who.int/ebola/en/current-situation/ebola-situation-report)

- Robert Koch Institute (RKI). Fact sheets, rare and imported infectious diseases (2011).

- Beeching NJ, et al: Travellers and viral haemorrhagic fevers: what are the risks? Int J Antimicrob Agents 2010; 36(Suppl 1): S26-35.

- Fhogartaigh CN, et al: Viral haemorrhagic fever. Clin Med 2015; 15(2): 61-66.

- Schieffelin JS, et al: Clinical Illness and Outcomes in Patients with Ebola in Sierra Leone. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(22): 2092-2100.

- Freedman DO, et al: Spectrum of Disease and Relation to Place of Exposure among Ill Returned Travelers. N Engl J Med 2006; 354(2): 119-130.

- Harvey K, et al: Surveillance for travel-related disease-GeoSentinel Surveillance System, United States, 1997-2011. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 62(3): 1-23.

- Leder K, et al: Travel-associated illness trends and clusters, 2000-2010. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19(7): 1049-1073.

- Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH). Viral Hemorrhagic Fever (VHF). June 6, 2008. (www.bag.admin.ch/themen/medizin/00682/00684/01111/index.html?lang=de)

- Chevalier MS, et al: Ebola virus disease cluster in the United States-Dallas County, Texas, 2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014; 63(46): 1087-1088.

- Price VA, et al: General physicians do not take adequate travel histories. J Travel Med 2011; 18(4): 271-274.

- Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH). Ebola. April 9, 2015 (www.bag.admin.ch/themen/medizin/00682/00684/01061/index.html?lang=de)

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Ebola Virus Disease, Outpatient and Ambulatory Care Settings. January 22, 2015 (www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/healthcare-us/outpatient-settings/index.html)

- Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA). Focus Ebola. April 16, 2015 (www.eda.admin.ch/eda/de/home/vertretungen-und-reisehinweise/fokus/focus3.html)

- World Health Organization (WHO). Travel and transport risk assessment: Interim guidance for public health authorities and the transport sector. September 10, 2014. (www.who.int/ith/updates/20140910/en)

- Agnandji ST, et al: Phase 1 Trials of rVSV Ebola Vaccine in Africa and Europe – Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med 2015 Apr 1; Epub ahead of print.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(5): 17-21