One of the main components of being a doctor is to provide the best possible care to patients. The quality of services in Switzerland does not need to hide in a global comparison. This quality must be safeguarded.

The Swiss healthcare system is considered the second most expensive in the world after the USA. The quality of the services is impressive, but not in proportion to the costs. Several studies indicate that half of all adverse medical events would be preventable [1]. An essential part of a physician’s job is to provide patients with the best possible care. Therefore, quality assurance plays an important role.

The protection of the patient and thus the obligation of physicians to use effective therapies has its roots as early as the 18th century B.C. In ancient Egypt, draconian punishments were imposed if a physician injured his patient or used impure tools [2]. In the mid-1960s, Avedis Donabedian developed a quality model, which is still recognized today, that distinguished in a two-dimensional grid between structural, process, and outcome quality, as well as technical, interpersonal, and moral or ethical quality [3].

Areas of responsibility

Medicine is considered a profession in its own right. This includes defining the scope of activity and services rendered, education and training, as well as admission to professional training itself and conducting research on its own activity. With the introduction of the Health Insurance Act (KVG) in 1996, this professional self-regulation was restricted. It is now up to the Federal Council to review and actively address quality assurance. On the one hand, quality assurance and promotion is now handed over to the federal government by the respective legislation. The latter issues guidelines in the field of education and professional practice, regulates the requirements for the accreditation of service providers and establishes values for the development and publication of quality information. The cantons are also the licensing authority, assess the quality and efficiency of hospitals, and support the binding nature of the federal government’s quality assurance measures and quality measurements for service providers [1].

Patient safety writ large

Extensive experience in Germany and abroad has led to a situation in which mainly health professionals are concerned with the implementation of quality assurance systems. In particular, the spread of DRG systems has brought about a number of changes, e.g. the discussion of processes and treatment standards [4]. In Germany, hospitals were already obliged to implement quality management before the introduction of DRG systems [5]. In Switzerland, too, the federal government formulated a quality strategy before the introduction of the DRG system in 2012 (Table 1) [6]. This is implemented by the Foundation for Patient Safety.

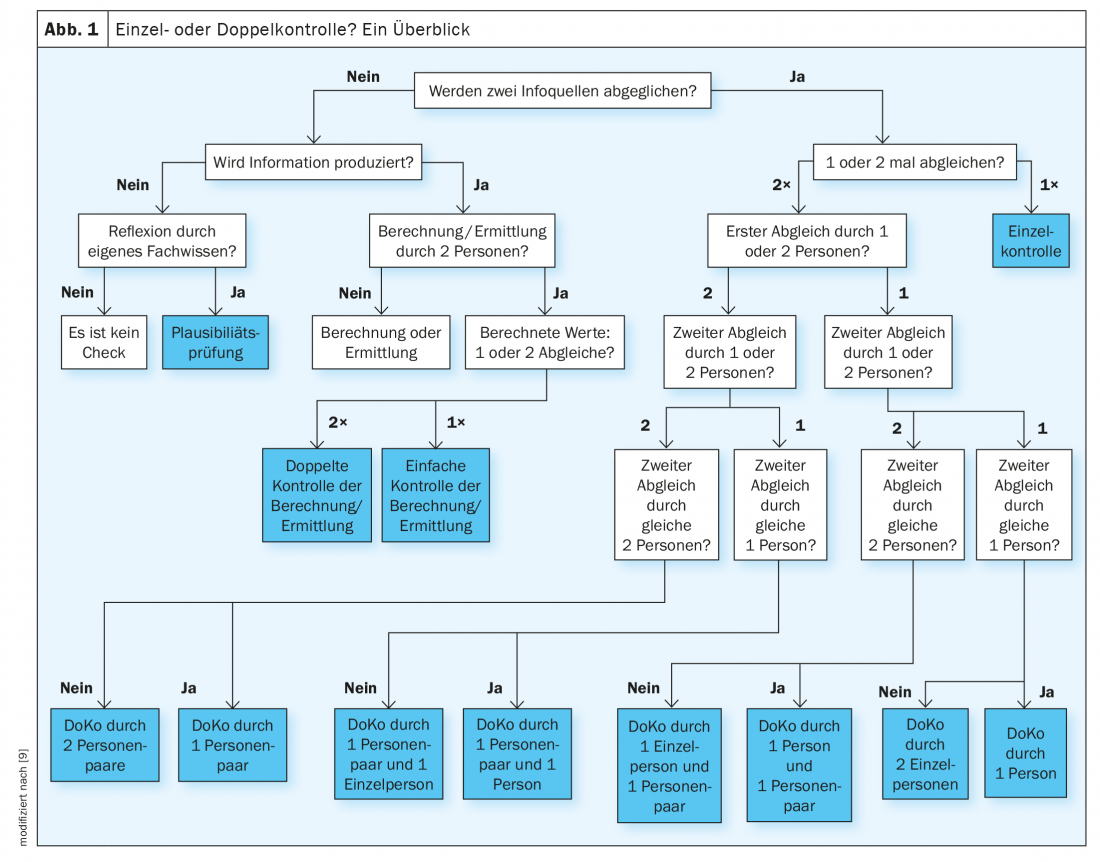

The foundation’s main goal is to identify risks, deal with and avoid mistakes, and improve the safety culture [7]. All care sectors from inpatient to outpatient to long-term and psychiatric are covered. In addition to medication, digitalization, design and communication, surgery and oncology are the main focus of the activity. For example, one project addresses double-checking. Patient care safety checks are routine in the clinical setting. For high-risk drugs, such as those used in oncology patients, double-checking is usually used. However, since no national standards have yet been adopted, this does not always run optimally. The findings obtained in the course of a research project were therefore incorporated into recommendations of the foundation [8]. Accordingly, a double check is defined as a double matching of information originating from at least two information sources. In a double check, the same adjustment is performed twice (Fig. 1).

Improve resources

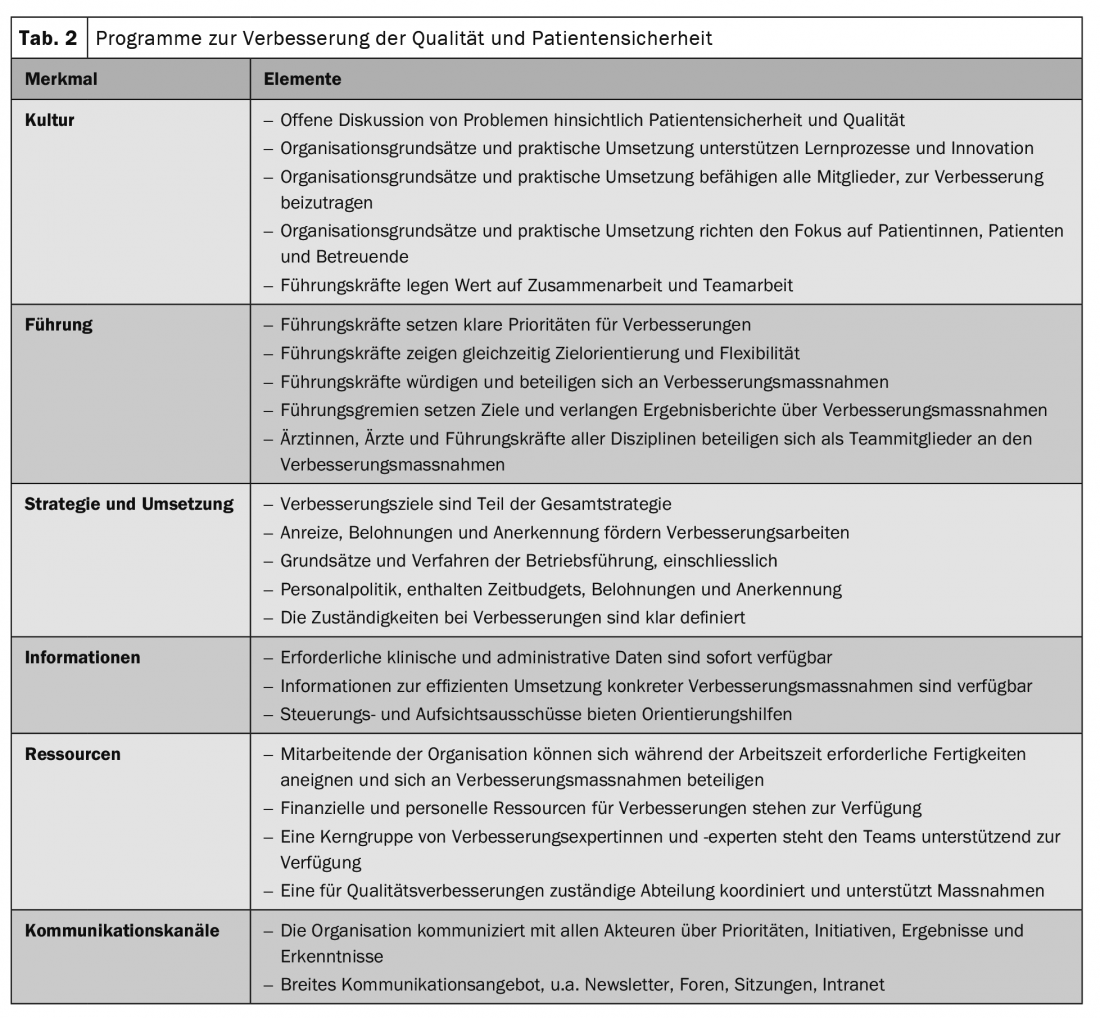

However, information and measures on patient safety and quality of care alone are not enough to improve health care. Health care facilities must also have the resources to implement them in their day-to-day practice. This requires an improved organization that implements the measures effectively and reliably. For this purpose, all parties involved should cooperate – from hospital management to caring relatives (Tab. 2) [9].

Optimized practice processes

A lot is also happening in outpatient care. The focus of any quality management in the practice is patient-oriented process optimization and patient satisfaction. In doing so, the systems can be adapted to one’s own needs and the needs of employees and patients. Optimized practice procedures and risk minimization can save from human and economic harm. In Switzerland, there are now several foundations whose focus is on the development of quality programs for practices and physician networks (e.g. EQUAM, QBM, GMP or MFA). Primary goals are to raise awareness among participating physicians and staff, clarify the basic structures of medical practices, and provide internal benchmarking to initiate quality improvement processes at participating practices.

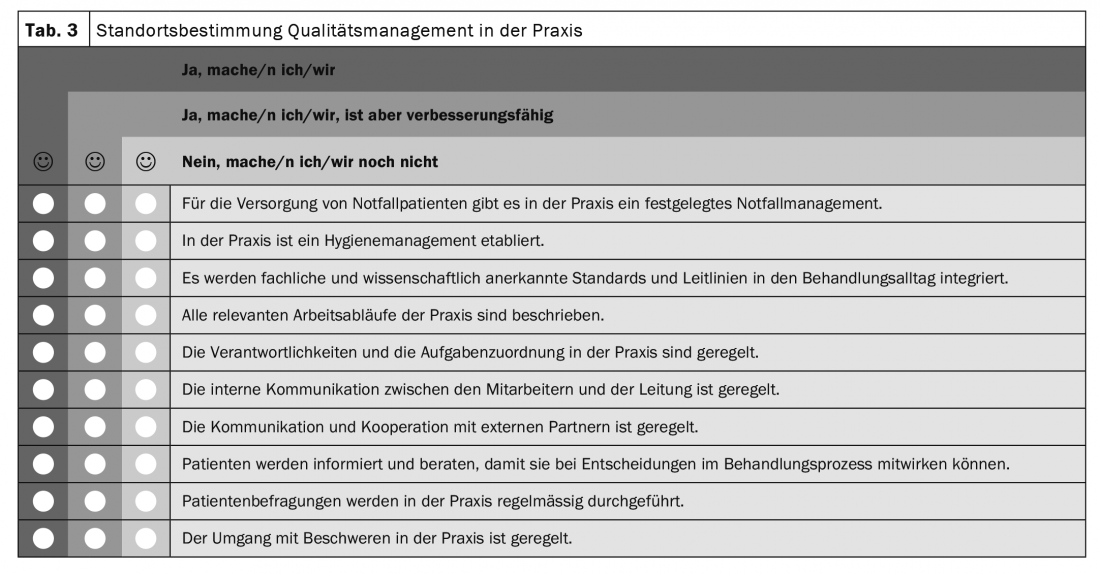

The main focus of quality management in the outpatient setting is on error management, patient information and education, and interface management. These priorities are followed by team meetings, complaint management, the regulation of responsibilities and competencies, risk management, and the measurement and evaluation of quality objectives. Only the patients are not yet effectively involved in the processes. Patient surveys are virtually non-existent (Table 3) .

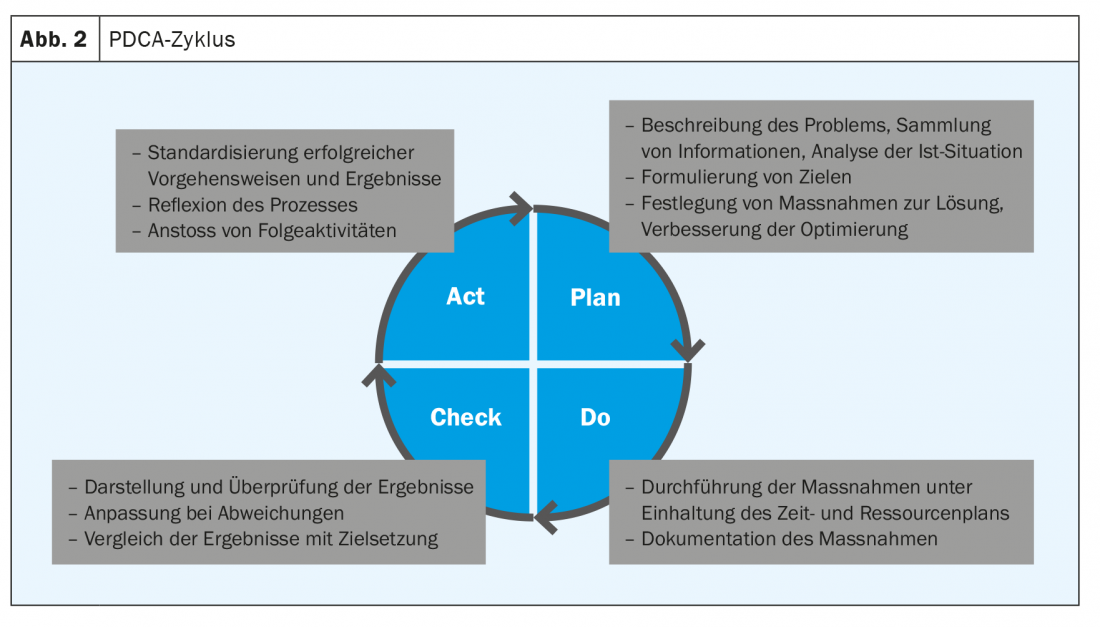

The PDCA cycle of improvement

The so-called PDCA cycle can be helpful for the implementation of quality assurance. It is based on the “Plan-Do-Check-Act” principle. Planning is based on a self-assessment with the definition of concrete goals, measures and responsibilities. Implementation and systematic review follow. If the targeted goals are not achieved, either the measures or the goals are adjusted (Fig. 2) [10].

Literature:

- www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/versicherungen/krankenversicherung/krankenversicherung-qualitaetssicherung.html (last call on 20.06.2022)

- https://saez.ch/article/doi/bms.2017.05675 (last call on 20.06.2022)

- http://neuron.mefst.hr/docs/CMJ/issues/2003/44/5/29_BookRev.pdf (last call on 20.06.2022)

- Nylenna M, Bjertnages O, Sperre Saunes I, Lindahl AK (2015): What is Good Quality of Health Care? In: Professions and Professionalism, Vol 5, No 1, 1-16.

- Güntert B, Offermanns G (2001). Quality management models for health care, in: lögd (ed.), Qualitätsmanagement im ÖGD, lögd, vol. 9, Bielefeld, pp. 13-3.

- FOPH (2009). Quality Strategy of the Confederation in the Swiss Health Care System, EDI, Bern.

- www.patientensicherheit.ch/ (last call on 20.06.2022)

- www.patientensicherheit.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/2_Forschung_und_Entwicklung/DOKO/Doppelkontrolle_Empfehlung_DE.pdf (last call on 20.06.2022)

- Vincent C, Staines A: (2019) Improving the quality and patient safety of Swiss health care.

- Bern: Federal Office of Public Health, www.qualitaetsmanagement.me/pdca_zyklus (last call on 20.06.2022)

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2022; 10(4): 13-16.