In certain emergency situations in family practice, the rapid availability of laboratory values plays a crucial role, as laboratory values are of central importance in the process of establishing a diagnosis. This applies, for example, to the differential diagnosis of dyspnea/cardiac failure, hyperglycemia, acute myocardial infarction, or acute renal failure.

In certain emergency situations in family practice, the rapid availability of laboratory values plays a crucial role, as laboratory values are of central importance in the process of establishing a diagnosis. This applies, for example, to the differential diagnosis of dyspnea/cardiac failure, hyperglycemia, acute myocardial infarction, or acute renal failure. In the following, these four emergency situations are explained in more detail with a special focus on the laboratory methods used in the practice laboratory.

Heart failure/dyspnea

Acute dyspnea can be caused by acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or heart failure, among many other common causes such as pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, or pulmonary edema. For the diagnosis of dyspnea, B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal-pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) have become important pillars in family practice, in addition to ECG, chest x-ray, and D-dimer determination (if thromboembolism is suspected).

Early diagnosis and treatment of heart failure means a better prognosis for patients. Natriuretic peptides are secreted when there is excessive wall stress on the myocardium. First, proBNP is synthesized, which is cleaved to the inactive N-terminal fragment (NT-proBNP) and the biologically active BNP.

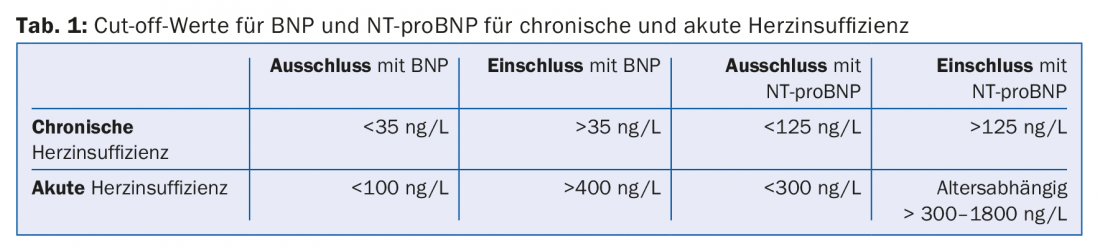

Both markers have been thoroughly investigated in many large studies. They are best suited to help distinguish between pulmonary- and cardiac-related dyspnea in an acute situation: if BNP is below 100 ng/L or NT-proBNP below 300 ng/L, acute heart failure is unlikely. In addition, they may contribute to more efficient treatment in cases of suspected chronic heart failure, as low BNP or NT-proBNP levels (<35 ng/l resp. <125 ng/l) can exclude chronic heart failure with a negative predictive value of about 98% (Tab. 1) . It should be noted especially for NT-proBNP that the cut-off values for the assessment of the probability of acute heart failure (inclusion) are strongly age-dependent. Similarly, exclusion limits must be set higher in patients with renal insufficiency. In contrast, BNP values are generally lower in very obese patients.

Meanwhile, some studies provide evidence that NT-proBNP in particular is useful for monitoring the progression of heart failure therapy. Newer point-of-care (POC) tests even allow BNP to be determined from capillary blood – but the values show large discrepancies with venous determinations and the imprecision is too high at 20%.

Hyperglycemias

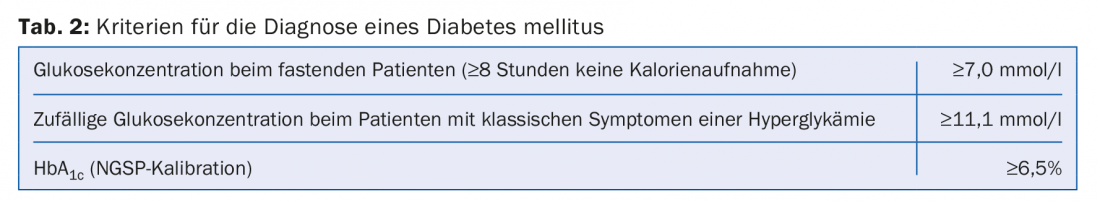

Hyperglycemia can be clearly diagnosed by measuring an elevated blood glucose concentration. Since the blood glucose concentration changes greatly with food, the individual measured value must be interpreted in relation to the patient’s food intake (Tab.2). Hyperglycemia can occur in patients with known diabetes mellitus, but also in patients with an acute illness leading to hyperglycemia or in patients with an initial diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus. As an additional parameter, measurement of glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) can be very helpful, especially in the differential diagnosis of an acute derailment of blood glucose (e.g., due to an acute illness) and a type 2 diabetes mellitus that has existed for some time.

Quite crucial for a correct diagnosis is the analyzer used for the measurement. Depending on the type and age of the instrument, completely different analytical requirements are met, resulting in very different accuracy and precision of the measurement. Measuring devices intended for patient self-monitoring must never be used for the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Other practice laboratory equipment generally meets the desired requirements.

Above a blood glucose concentration of 14 mmol/l, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) develops, especially in type 1 diabetics (but sometimes also in type 2 diabetics), which, depending on the blood glucose concentration, can lead to a sometimes massive pH decrease. The diagnosis of DKA in the primary care physician’s office can be made solely by measuring the ketone bodies in the urine with the urine test strip. However, it must be remembered that DKA mainly produces beta-hydroxybutyrate, which is not detected by the test strips. In case of moderate or severe ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar hyperglycemic derailment (glucose concentration >33.3 mmol/l), the patient must be referred to the emergency department of a hospital, as control of blood pH and intravenous therapy are necessary to correct it.

Acute heart attack

Diagnosing acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in the office is a not uncommon and important task for the primary care physician. How useful is it to use a point-of-care (POC) troponin test for this purpose? Basically, according to the current universal definition of ACS as per ESC 2015 [1], the detection of a rising or falling biomarker such as troponin along with at least one other criterion such as ischemic symptoms, ECG changes, etc. is mandatory.

However, it should be noted that most POC tests have a much higher detection limit of 100 ng/L (newer POC tests 50 ng/L) compared with current high-sensitivity troponin tests for large systems, which have a detection limit of 3 ng/L troponin T. Specifically, this means that in patients whose onset of pain is less than 6 h ago, ACS cannot be ruled out in any case on the basis of a negative POC troponin value. For example, when blood was drawn approximately 90 minutes after the onset of pain, troponin T was elevated with a newer POC test only in approximately 40% of patients with an AMI [2].

In cases of high-grade clinical suspicion of ACS – with or without ECG changes – patients should be hospitalized as soon as possible in any case, so that no time is lost by a test whose result has no influence on the decision anyway.

The situation is different, on the other hand, if the onset of pain can be proven to have occurred more than six hours ago and the 12-lead ECG is unremarkable. In this case, a POCT troponin test can provide important decision support regarding the need for hospitalization.

Acute renal failure

Acute renal failure can be triggered in patients with pre-damaged kidneys, for example, by the use of a non-steroidal analgesic. The diagnosis can be made very well with the determination of creatinine in serum, which is also carried out in many general practitioners’ practices. If acute renal failure is suspected, it must be possible to perform diagnostics very promptly; otherwise, the patient must be referred to a hospital so that rapid laboratory diagnostics can be performed there.

Creatinine determination is usually performed using the so-called Jaffé reaction. This is a very simple color reaction with picric acid, which is unfortunately prone to interference. Over time, most diagnostic manufacturers have optimized their tests so that a problem-free measurement is possible in the vast majority of patients. However, cephalosporins lead to significantly false results, which should not then be used to diagnose renal function.

The estimation of glomerular filtration rate can be done by using different formulas. Today, nephrology societies recommend the CKD-EPI-2009 formula for calculating glomerular filtration rate, which takes into account age and serum creatinine concentration. Correction factors must be used for certain populations (black skin color or origin from Japan).

In addition, urea can be determined in serum. With this parameter, however, it must be taken into account that its concentration depends on protein intake on the one hand, and on drinking quantity on the other, and is therefore subject to many influencing factors.

Much more common than acute renal failure is chronic renal failure, the course of which should be carefully monitored. In addition to the determination of creatinine and urea in serum, the determination of cystatin C can also be used here, since this parameter is much more sensitive than creatinine in indicating damage to the kidney, especially in an early phase of renal insufficiency.

Take-Home Messages

- Heart failure/dyspnea: BNP and NT-proBNP can be used as part of the diagnostic cascade for acute dyspnea, and these markers can also be used to screen for chronic heart failure in patients at risk.

- Hyperglycemia: In addition to the absolute blood glucose concentration, the determination of HbA1c can also be used to diagnose diabetes mellitus.

- Acute myocardial infarction: Diagnostics for the referral decision include the timing of symptom onset, any ECG changes, and, under certain circumstances, a point-of-care troponin test.

- Acute renal failure: Diagnosis is made by creatinine concentration.

Literature:

- De Vecchis R, Ariano C: Measuring B-Type Natriuretic Peptide From Capillary Blood or Venous Sample: Is It the Same? Cardiol Res 2016; 7(2): 51-58.

- Lucner A, et al: Fields of application and practical utility of the cardiac markers BNP and NT-proBNP. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2017; 142(5): 346-355.

- Scirica B: Use of biomarkers in predicting the onset, monirotirn the progession, and risk stratification for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Chem 2017; 63(1): 186-195.

- Sigrist S, Brändle M: Hyperglycemic emergency situations in adults. Swiss Med Forum 2015;15(33): 723-728.

- Roffi M, et al: 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients.

- Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2016; 37(3): 267-315.

- Stengaard C, et al: Quantitative point-of-care troponin T measurement for diagnosis and prognosis in patients with a suspected acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2013; 112(9): 1361-1366.

- Levin A, Stevens PE: Summary of KDIGO 2012 CKD Guideline: behind the scenes, need for guidance, and a framework for moving forward. Kidney Int 2014; 85(1): 49-61.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(9): 20-23