Abdominal aortic aneurysm nowadays can be treated both openly and with endovascular procedures. Which therapy is carried out should always be decided individually.

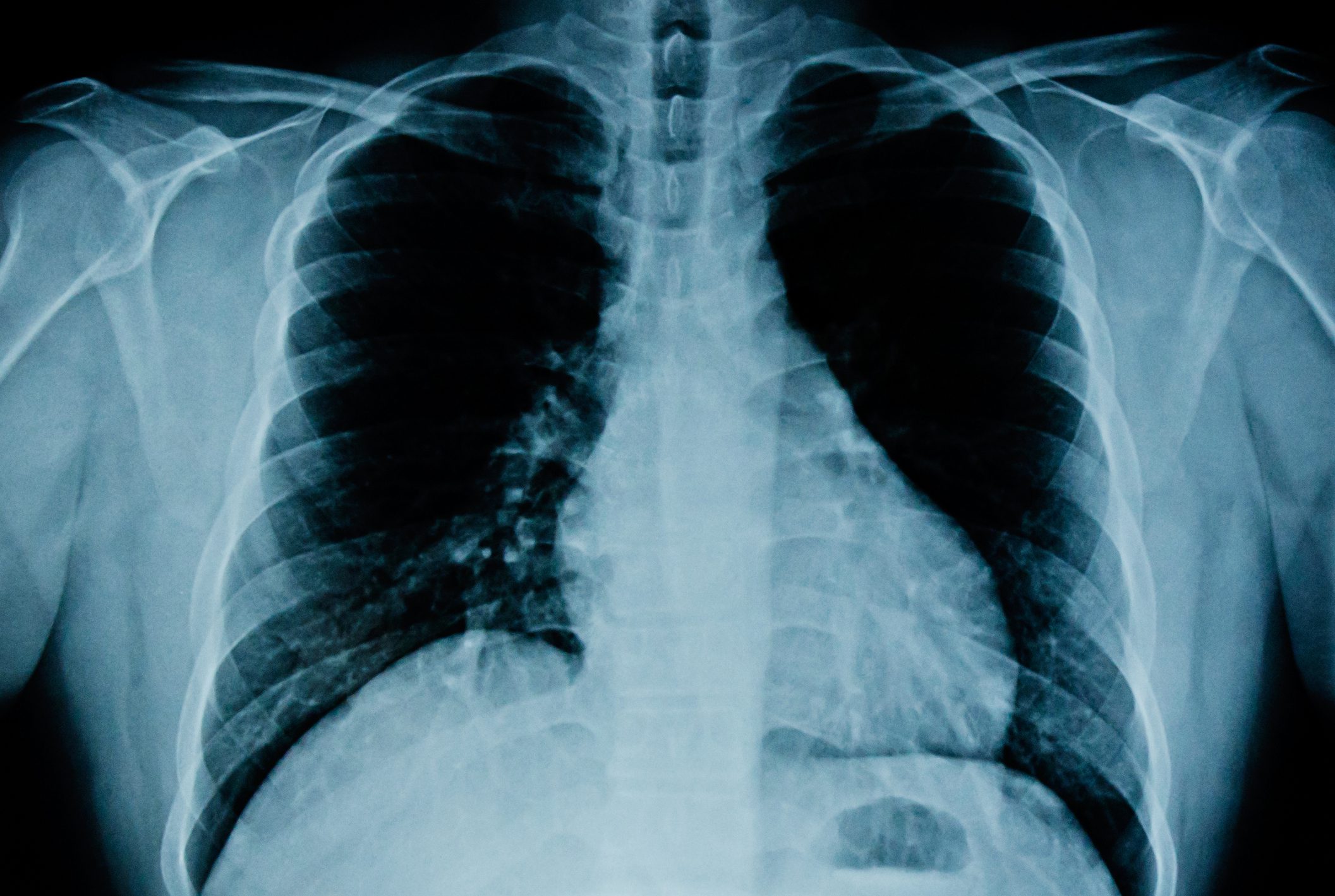

The term abdominal aortic aneurysm (BAA) is used to describe a pathologic dilatation (>3 cm in diameter) of the abdominal aorta. The most common is the infrarenal aortic aneurysm with onset below the renal arteries (Fig. 1). If the aneurysm begins at the level of the renal arteries or with renal arteries arising from the aneurysm, it is referred to as a juxta- or suprarenal aortic aneurysm. These anatomic differences in abdominal aortic aneurysms largely determine the treatment strategy.

The main risk factor for the development of BAA is smoking [1]. Other important risk factors include age, sex, atherosclerosis, arterial hypertension, ethnicity, and a positive family history. The current European guidelines for the treatment of BAA report a significant reduction in prevalence and incidence over the last 20 years [1]. This development is most likely due to the now reduced tobacco consumption and the increasing prescription of statins [2]. Nowadays, the prevalence is 1.7% in 65-year-old men and 0.7% in women over 60 [1]. Men are affected much more frequently than women in a ratio of 4:1.

A large meta-analysis of over 15 000 patients (RESCAN study) with a BAA between 3.0 and 5.5 cm showed no difference in aneurysm growth rate per year between men and women [3]. Both groups had a growth rate of 2.2 mm/year. On the other hand, the initial measured diameter (DM) plays a crucial role for further growth: a BAA with 3.0 cm DM grows 1.3 mm/year, a BAA with 5.0 cm DM grows 3.6 mm/year [3]. In smokers, an additional growth of another 0.35 mm/year can be expected [3].

Clinical manifestation and diagnostics

BAA is usually asymptomatic. Nonspecific abdominal or lumbar pain often leads to an incidental diagnosis. Clinical examination can detect a pulsatile mass in the abdomen, but this examination has a sensitivity of <50% and decreases in obese patients [4]. Therefore, abdominal palpation is not a safe method of examination. If symptomatic, BAA presents with pain on palpation or spontaneous pain in the back or abdomen. Rupture is accompanied by severe pain in the back/abdomen and often signs of hypovolemic shock (Fig. 2). Free rupture is associated with leakage of blood into the free abdominal cavity and is usually not survivable. The so-called covered rupture with spontaneously stopping hemorrhage in the retroperitoneal space has significantly better chances of survival. Extremely rarely, rupture may occur into a hollow organ and then be associated with the formation of an aorto-enteral or aorto-caval fistula.

Sonography of the abdomen is the examination method of choice with very high sensitivity and specificity [4]. Clear disadvantages of the method are examiner dependence, inaccurate examination in obese patients and intestinal gases, and variability of aortic diameter (up to 2 mm) due to cardiac cycle [4].

Computed tomography (CT) with contrast helps in accurate detection of aneurysm morphology and is necessary for treatment planning. Fine-slice (≤1 mm slice thickness) CT examinations allow high-resolution multiplanar reconstruction and precise measurements. The use of nephrotoxic contrast agent and radiation exposure are the main disadvantages of CT. Pre- or post-hydration of patients with sodium bicarbonate or saline does not provide any benefit in terms of renal function [5].

Treatment

Elective treatment of BAA is recommended in men from 55 mm in diameter and in women from 50 mm [1]. A growth rate of 5 mm in 6 months or 10 mm in a year is a sign of impending rupture and requires prompt treatment. Continued growth of the BAA over several years may ultimately lead to aneurysm rupture. Rupture of a BAA is associated with a mortality rate of up to 90%; depending on many patient-specific, technical, organizational, and hospital-associated factors [6].

BAA can be treated today with open and endovascular procedures. The treatment strategy depends on several factors and should be determined individually. Important roles are played by the operability of the patient, the anatomical features of the BAA, life expectancy, patient preference, and willingness for lifelong follow-up. The open procedure has a higher mortality risk of ≥5% within 30 days [7]. In contrast, the endovascular procedure has a mortality risk of 1% [7].

All patients with moderate physical activity who may have a metabolic equivalent (MET) ≥4 (e.g., walking two flights of stairs without rest) do not benefit from additional cardiac workup [1]. All others with MET <4 should have cardiac evaluation before BAA treatment. If necessary, relevant coronary or valvular heart disease should be rehabilitated before BAA treatment.

An open surgical procedure means replacement of the abdominal aorta using a tubular or Y-prosthesis via median laparotomy or left lumbotomy. In this case, the proximal anastomosis is performed as close as possible to the renal arteries (even in the case of a long aneurysm neck) to prevent subsequent dilatation of the infrarenal aortic segment (Fig.3). Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) or polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) can be used as a substitute material (Fig.3). There are no contraindications for open treatment regarding aortic morphology, with the exception of multiple preoperated abdomen.

The endovascular procedure uses an endograft to eliminate the aneurysm from the inside. The aneurysm wall remains completely intact. Therefore, a sufficient landing or sealing zone is essential for this procedure (Fig. 4). For example, a non-dilated segment below the renal arteries (= neck) of at least 10 mm length is required for good anchorage of the endograft [1]. A bifurcation and one or two iliac prostheses are placed over the femoral vessels, starting below the renal arteries and ending just before the iliac bifurcation on both sides (Fig. 5). The endovascular procedure can be performed under local anesthesia. This has positive effects on the postoperative course: shorter hospital stay and fewer general complications [8].

Endoleak

Endoleak is defined as persistent blood flow in the aneurysm sac outside the endograft. The different endoleak types and their occurrence after the procedure are shown in Table 1. Type I and type III endoleaks must be treated rapidly once identified because they are associated with high perfusion pressure and can rapidly induce secondary aneurysm rupture. Endoleak type II is the most common. This endoleak can also lead to secondary size increase and rupture. Therefore, clear size progression of the aneurysm sac through an endoleak type II should trigger appropriate treatment.

Discussion

The main advantage of endovascular treatment, compared with open replacement, is the lower early postoperative mortality and morbidity rate [9]. In recent decades, the number of endovascular treatments increased with a concomitant decrease in early postoperative mortality and morbidity rates, despite increasing treatment of older and sicker patients [9]. At the same time, the operation time and hospital stay became significantly shorter. Treatment in a postgraduate center, especially one with a high caseload, yields better outcomes with lower mortality and complication rates [10].

However, the early postoperative advantage is lost after two years at the latest, and the medium-term mortality rate is then identical for both procedures. After three years, the number of deaths due to secondary aneurysm rupture after endovascular treatment even increases [7]. Ruptures result from complications associated with the endograft: migrations, kinking, endoleaks, and corresponding reperfusion of the aneurysm sac. Endoleaks are the Achilles heel of endovascular treatment and the reason for the significantly higher re-intervention rate after endovascular treatment of ≥25% during 5 to 10 years of follow-up [7]. On average, patients with treated BAAs live approximately 9 years after the procedure [1].

Close monitoring by ultrasound (with or without contrast agent) or CT angiography is indicated for life in all patients after endovascular treatment. The current recommendation is to perform a checkup within 30 days of the procedure, at 6 months, and annually thereafter [1,10]. In patients with open aortic surgery, the frequency of follow-up is recommended to be much less frequent, such as every 5 years by ultrasound or CT angiography.

Currently, both treatment methods are about equally expensive worldwide. While the open procedures with postoperative complications are more expensive than the endovascular procedures (including the implants), the number of controls and re-interventions is significantly more costly for the endovascular procedures over years.

Summary

Current evidence shows that endovascular treatment is superior to open replacement early postoperatively. However, long-term survival is comparable. The reintervention rate during follow-up, especially 8 to 10 years after endovascular treatment, is significantly higher than after open replacement. Therefore, lifelong follow-up is important. Although endovascular treatment can be offered to almost any patient, it is more appropriate to recommend open replacement to younger and fitter patients with a life expectancy of >10-15 years.

Literature:

- Wahnhainen A. et al: European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2019 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-iliac Artery Aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2019; 57: 8-93.

- Lederle FA: The rise and fall of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Circulation 2011; 124: 1097-1099.

- Sweeting MJ, et al. (RESCAN colalborators): Meta-analysis of individual patient data to examine factors affecting the growth and the rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg 2012; 99: 655-65.

- Long A, et al: Measuring the maximum diameter of native abdominal aortic aneurysms: review and critical analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2012; 43: 515-524.

- Kooiman J, et al: A randomized comparison of 1-h sodium bicarbonate hydration versus standard peri-procedural saline hydration in patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing intravenous contrast-enhanced computerized tomography. Nephrol Dial Transpl 2014; 29: 1029-1036.

- Karthikesalingan A, et al. Mortality from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms: clinical lessons from a comparison of outcomes in England and the USA. Lancet 2014; 383: 963-969.

- Powell JT, et al. Meta-analysis of individual-patient data from EVAR-1, DREAM, OVER and ACE trials comparing outcomes of endovascular or open repair for abdominal aortic aneurysm over 5 years. Br J Surg 2017; 104: 166-178.

- Ruppert V, et al. Influence of anesthesia type on outcome after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair: an analysis based on EUROSTAR data. J Vasc Surg 2006; 44: 16-21.

- Patel R, et al. Endovascular versus open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm in 15-years’ follow-up of the UK endovascular aneurysm repair trial (EVAR trial 1): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 388: 2366-2374.

- Chaikof EL, et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 2018; 67: 2-77.

CARDIOVASC 2019; 18(3): 30-33