The pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) has not yet been fully clarified; it is assumed that there are multifactorial interactions. The most important risk factors and comorbidities include smoking, obesity and metabolic syndrome. A multimodal treatment approach is generally recommended. In addition to non-drug measures and topical preparations, system therapies, surgical interventions and other therapeutic modalities are also used depending on the severity. In addition to adalimumab, secukinumab has also been available as a biologic in Switzerland since 2023.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), also known as “acne inversa”, is a chronic, recurrent, mutilating skin disease of the terminal hair follicle gland apparatus characterized by painful inflammatory nodular lesions with abscesses and fistula formation in the apocrine gland-bearing areas of the body (Fig. 1) [1,39,49]. Predilection sites include axillary, inguinal, and perianal regions [1]. Data on the prevalence of HS varies; in Central Europe, it is currently assumed to be around 1% [14]. HS usually manifests itself for the first time after puberty and peaks at around 20-25 years of age. Depending on the study, the gender ratio of women to men is given as 1:2 to 1:5 [2,3].

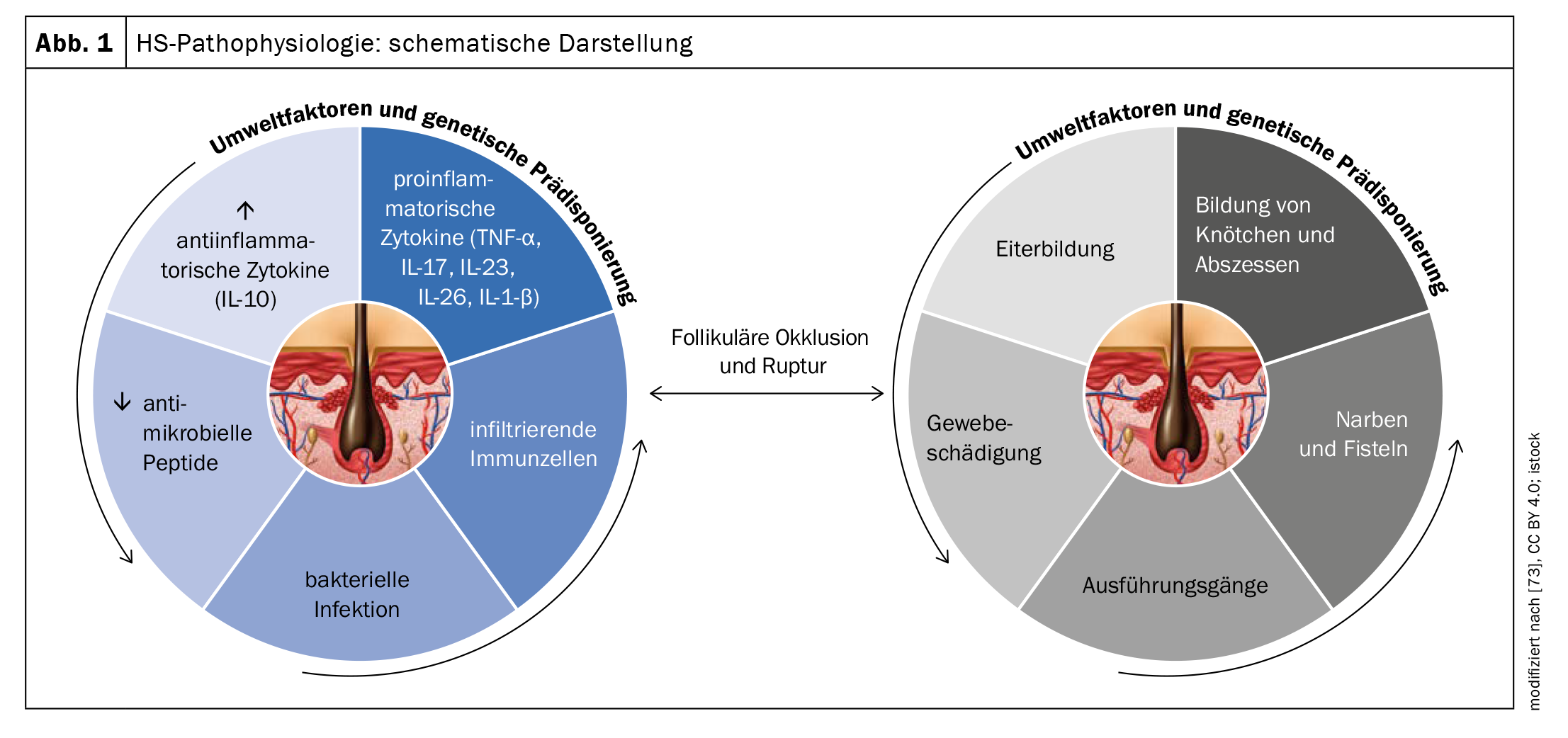

The exact pathogenesis of HS is not yet fully understood, but it is assumed that a combination of genetic, hormonal and environmental factors contribute to its development (Fig. 1). The fact that 35-40% have a positive family history suggests genetic involvement. In terms of pathomechanism, analyses of biopsies indicate that HS is initiated due to occlusion of the terminal hair follicle in response to hyperkeratinization leading to nodule/cyst formation and eventual ruptured follicular epithelium [4–8]. This results in chronic inflammation with sinus and fistula formation and extensive dermal scarring.

Clinical features and diagnosis

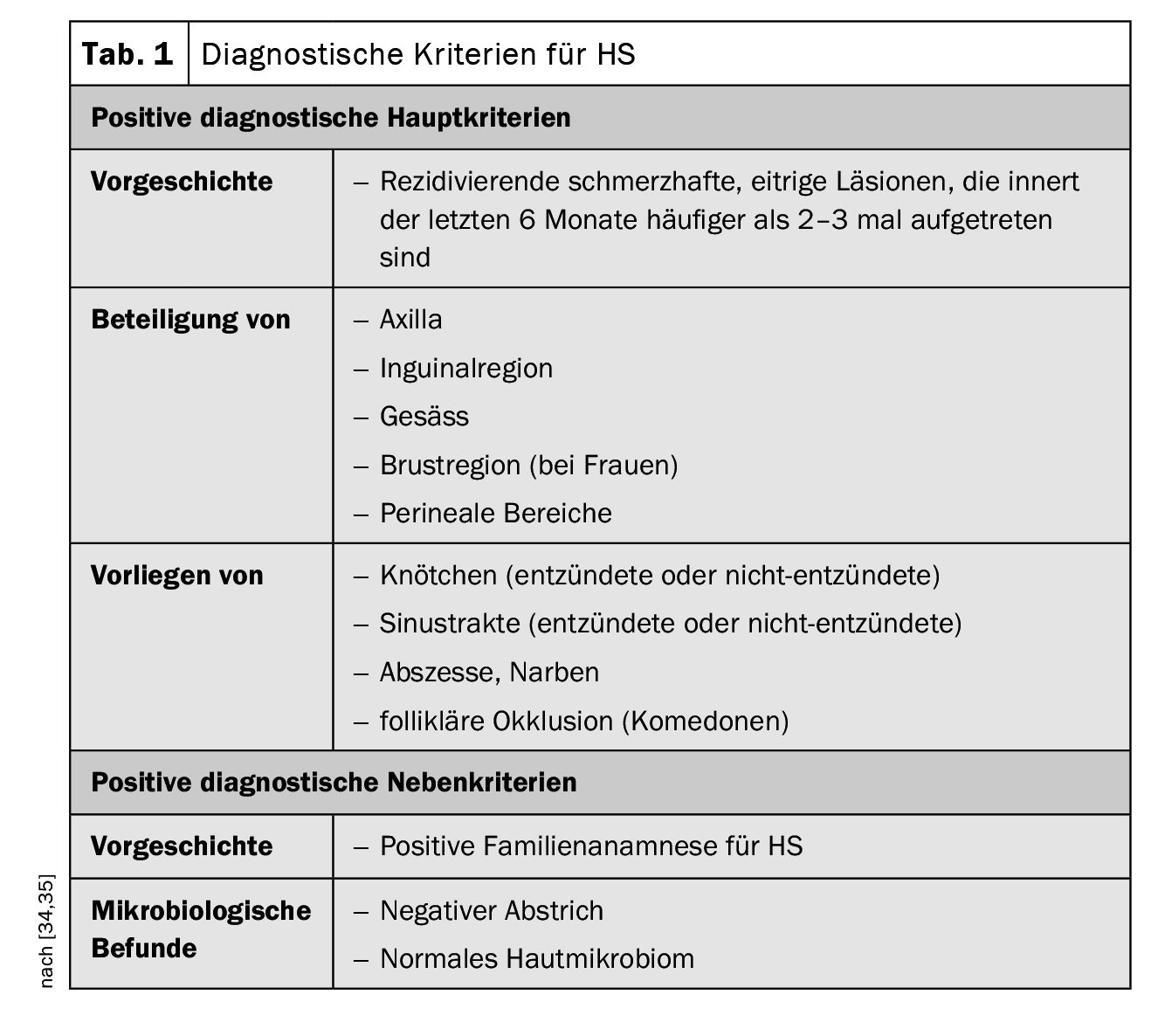

The clinical presentation of HS is characterized by recurrent inflammation that has occurred more than two to three times in the previous six months in the form of nodules, fistula tracts and/or scarring, particularly in regions of body folds [34,45]. The disease is often confused with common abscesses or folliculitis in the early stages. In a prospective study, the average latency until HS was established as the correct diagnosis was 7.2 to 8.7 years [35]. If HS is not diagnosed in time and treated adequately, the inflammatory process can progress, leading to tissue destruction over time. [47]. But the symptoms can also have serious psychosocial consequences. Bacterial infections, fistula formation and contractures can result in restricted mobility and are very stressful for patients, as empirical studies on quality of life show (Box) [9]. Clinical examination is central in the diagnostic workup of HS. Skin biopsies are not usually necessary, but may be useful to rule out a differential diagnosis with a Gram-positive bacterial cause (e.g. boils or carbuncles) [34]. The three main clinical features of HS are [1,16]:

- Typical anatomical localization (axillae, groin, buttocks, breast, perianal, perigenital),

- Typical lesions: deep-seated, painful lumps; abscesses; draining fistulas; scarring),

- Recurrent or chronic course

The diagnostic criteria postulated in the Swiss practice recommendations published in 2017 are summarized in Table 1; they are based on the three main characteristics mentioned [16,34,35]. There is currently no international consensus on the scores to be used for HS, but the Hurley stages and Sartorius scoring are the most commonly used [17,34,35]. According to the Hurley classification, the following three degrees of severity are distinguished depending on the clinical manifestation [17,46]:

Stage I: Isolated, single or multiple painful abscesses, no scar strands;

Stage II: Recurrent painful abscesses with stranding and scarring, solitary or multiple, but not extensive;

Stage III: Diffuse, squamous, inflammatory, painful infiltrations, or multiple interconnected strands and abscesses. There is a risk of joint contractures as a result of pain-related restriction of movement.

Level I HS is the most common (65%), followed by Level II (31%) and Level III (4%) [17]. In the Sartorius score, the number of inflammatory nodules, abscesses, fistulas, and affected areas are recorded and assigned points. Another classification system is the International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score System (IHS4). All inflamed lesions are evaluated and added together, whereby an inflamed nodule counts once, an abscess counts twice and a draining fistula counts four times. The total results in a classification into three degrees of severity (mild, moderate, severe) [50].

| High “burden of disease” Empirical data show that quality of life, operationalized using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), is significantly impaired in patients, with the extent of the burden varying depending on the severity of the symptoms: The mean DLQI was 5.77 for Hurley stage I, 13.1 for Hurley stage II and 20.4 for Hurley stage III. These are high values considering that in moderate to severe psoriasis, the DLQI averages 12-13 [10,11]. Pain was perceived as most distressing by 85% of patients with HS, followed by swelling/inflammation and tenderness [12]. Impairment may result in inability to work, and foul odors and stains on clothing caused by purulent abscesses may lead to social stigma . |

Risk factors and comorbidities associated with HS

The severity and course of HS correlate with the body mass index (BMI) and, according to several studies, an above-average number of HS patients are smokers (70-90%). Revuz et al. found an odds ratio ( OR) of 4.42 for obese patients (BMI >30) and 12.55 for smoking compared to healthy controls [2]. Another study by Miller et al. found an OR of 6.38 for obesity [20]. The risk of HS patients developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (OR=5.74) or metabolic syndrome (OR=3.89) is significantly increased [20]. Overall, the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors is significantly increased in individuals with HS compared with healthy individuals .

With regard to the progression of HS, in a retrospective study of 846 people, the following five factors were associated with an increased risk of progression from Hurley stage I to II or III: male gender, disease duration, BMI, smoking pack-years and lesion location [22]. Other trigger factors of HS include mechanical irritation and certain comorbid conditions (e.g., polycystic ovary syndrome and depression) [23–26]. Some studies report increased comorbidity rates of HS and other inflammatory diseases. In addition to polycystic ovary syndrome, this also applies to inflammatory bowel disease and pyoderma gangraenosum .

Multifactorial etiopathogenesis and dysregulation of the immune system

Genetic predisposition, lifestyle factors (especially smoking and obesity), hormonal components and dysfunctional immunological processes are involved in both the development and maintenance of the disease [51,65]. More recently, the hypothesis has been postulated that the interaction of endogenous and exogenous factors causes activation of the innate immune system [49]. This results in perifollicular inflammation, hyperkeratosis and hyperplasia of the follicular epithelium, particularly in the area of the infundibulum, which leads to follicular closure [52]. Dilation and rupture of the hair follicle induce an intense inflammatory immune response associated with the recruitment of neutrophils, macrophages, B cells, Th1 and Th17 cells into the skin, leading to inflammatory nodules or the formation of abscesses [51].

Proinflammatory signaling pathways contribute significantly to the development of HS. In the lesional skin of HS patients, the increased production of a large number of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17, IL-23, IL-32, IL-36 and TNF-α) has been demonstrated as an indication of immunological dysregulation [51,53–56]. Certain pathways appear to be of particular importance for HS pathogenesis [53]. Several studies have shown that the secretion of IL-23 and IL-12 leads to a Th17-dominant immune response and keratinocytic hyperplasia [56,58]. IL-23 induces IL-17-producing T helper cells, which infiltrate the dermis in HS lesions [59]. It is known that the IL-17 family is involved in the pathogenesis of various autoimmune diseases. IL-17 also plays an essential role in host defense against extracellular bacteria and fungi, and has been shown to increase the expression of skin antimicrobial peptides/alarmins [58]. Blocking IL-17 therefore also appears to be a valid therapeutic approach for HS [58].

As hidradenitis suppurativa progresses, increased levels of TNF, IL-1β, IL-17, caspase-1 and IL-10 are found in the tissue, leading to the recruitment of neutrophils, mast cells and monocytes, which differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells [59–61,65]. Recent findings also indicate that an autoinflammatory mechanism is involved in HS: HS skin, for example, shows increased formation of neutrophil extracellular networks (NET) [65]. Immune responses to neutrophil and NET-related antigens have been associated with increased immune dysregulation and inflammation [62].

Scarring of the previously inflamed tissue can lead to movement restrictions in the long term [58–60]. The development of scarring and sinus tracts is associated with transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and the adhesion molecule ICAM-1 [58]. Bacterial superinfection of established lesions can contribute to the maintenance of chronic inflammation [61]. The main bacterial species isolated in HS lesions include Gram-positive cocci, including Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus species, coagulase-negative staphylococci, Proteus mirabilis and mixed anaerobic bacteria [61]. Staphylococcus epidermidis and Corynebacterium spp. as well as atypical bacteria such as Proteus mirabilis, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter aerogens and Enterococcus faecalis were detected in microbiological samples from draining lymph nodes in HS patients following surgical excision [64].

Multimodal treatment – anti-IL-17A-Ak as a new therapeutic strategy

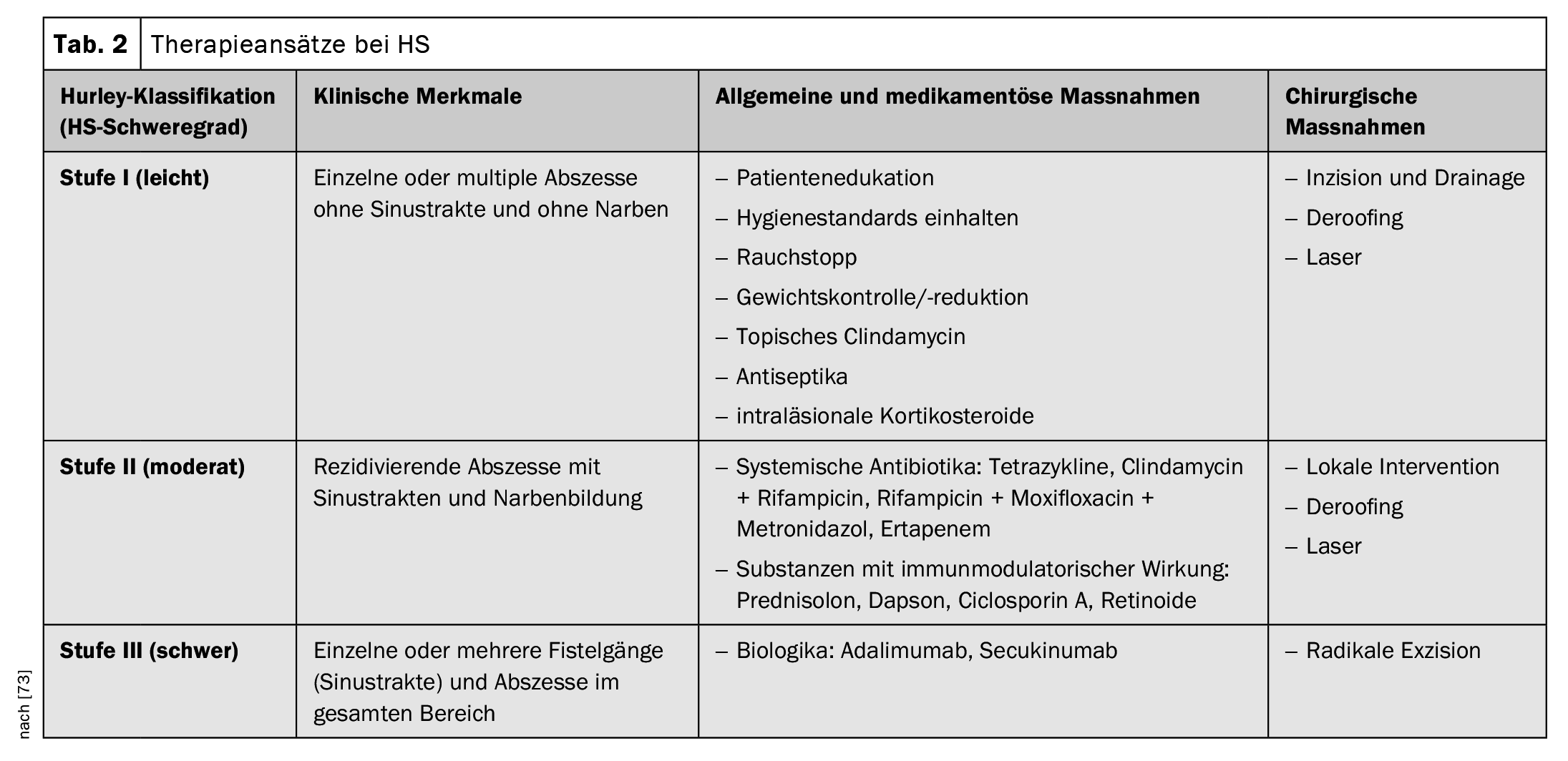

The Swiss treatment recommendations published in 2017 refer to various disease modalities or starting points for treatment, whereby the recommended treatment options are adapted to the severity of the HS (Table 2) [34,35]. In terms of drug treatment options, this year’s Swissmedic approval of the IL-17-A inhibitor secukinumab represents an important expansion of the treatment spectrum.

Pharmacotherapy: The recommended treatment algorithm is based firstly on the Hurley severity scale (I-III) and secondly on disease-specific characteristics.

- Topical preparations: Topical disinfectants (e.g. triclosan, ammonium bituminosulphonate) or topical antibiotics (e.g. clindamycin solution) are recommended to prevent bacterial overinfection and to reduce inflammation and maceration [30,34,35]. Inflamed nodules can be treated with intralesional steroids [34,35].

- Systemic antibiotics: If topical agents are not sufficient, systemic antibiotics are usually administered. Doxycycline (50-200 mg daily, for 3-6 months) or rifampicin in combination with clindamycin (300 mg twice daily, for up to three months) are suggested, zinc gluconate (3× 30 mg, daily) can be added as a combination [31,34,35].

- Conventional systemic therapeutics and biologics: Secukinumab or adalimumab can be prescribed in the recommended dosage for active moderate to severe HS that has responded inadequately to systemic antibiotic therapy [72]. Alternatively, systemic acitretin (0.2-0.5 mg/kg per day), dapsone (50-150 mg daily), metformin, ciclosporin A or systemic steroids can be used [34,35]. Efficacy is usually assessed in clinical studies using the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response Score (HiSCR) [48]. HiSCR is defined as ≥50% reduction in inflammatory lesions (sum of abscesses and inflammatory nodules) and no increase in the number of abscesses and secreting fistulas compared to baseline [48].

- Painkillers: The pain can come from the inflamed lumps and abscesses, but scars, keloids, open ulcerations, lymphoedema, anal fissures or arthritis can also cause pain. In addition to topical preparations (e.g. lidocaine and anti-inflammatory agents), systemic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, atypical anticonvulsants (e.g. gabapentin or pregabalin) and serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors are mentioned in the specialist literature [70,71]. Duloxetine has proven effective for comorbid depression [71].

Surgical measures and laser excision: local excision of single lesions is recommended only in localized, well-circumscribed cases of Hurley I and II [1]. In all other cases, a wide scalpel orCO2 laser excision of the skin, including parts of the fatty tissue of the entire affected area, should be considered [1]. The exact surgical treatment plan – like conventional therapy – must be clarified individually and in consultation with the patient. Physiotherapeutic measures are indicated until the wound has healed completely.

Lifestyle factors: In order to promote the quality of life of HS patients, the relationship between lifestyle factors and HS should be emphasized in patient education. Nicotine is thought to induce epidermal hyperplasia and follicular congestion [67]. In addition, HS patients already have a high cardiovascular risk, which is exacerbated by smoking [68]. In addition to smoking, obesity is also associated with the severity of the disease. There is a general consensus that smoking cessation and weight reduction are important measures to counteract an exacerbation of the disease [2,66]. International guidelines explicitly state that weight reduction can have a positive effect on disease severity in overweight people with HS and that patients should be advised accordingly [68]. In addition, loose-fitting clothing is recommended to avoid mechanical stress [68].

Psychosocial support: HS has a negative impact on quality of life and can lead to depressive disorders and social disintegration. There is empirical evidence that HS patients experience a high level of distress and it is advised to include not only the physical symptoms but also the psychological dimensions of the disease in disease management [68,69]. In a study published in 2019, which included 110 HS patients (mean age 38±12 years; 61 female, 49 male), significant correlations were found between the Skindex-29 and the Sartorius score (symptoms: p=0.024; emotions: p=0.019; functional status: p=0.002) [69]. In addition, the VAS for pain correlated significantly with the DLQI (p=0.000) and BMI was associated with the Sartorius score (p=0.038) [69].

Take-Home Messages

- Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease with recurrent lumps, abscesses and fistula and scar formation in regions of the body with apocrine glands (armpit, groin, perianal and perineal region). In about 40% of cases, the family history is positive. Women are affected more often than men.

- The most important risk factors and comorbidities include smoking, obesity and metabolic syndrome. However, spondyloarthropathies and chronic inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are also represented with above-average frequency in this patient population.

- The pathogenesis has not yet been fully clarified; it is assumed that there are multifactorial interactions. Among other things, a strong expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines was detected in skin lesions of HS patients. This is a starting point for newer systemic therapy options such as biologics.

- A multimodal treatment approach is generally advocated. In addition to lifestyle factors and topical preparations, system therapies, surgical interventions and other methods are used depending on the severity. In addition to adalimumab, secukinumab has also been available as a biologic in Switzerland since 2023. Pain management and the inclusion of psychosocial aspects are important accompanying measures.

Literature:

- Zouboulis CC, et al: S1 guideline for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa (number ICD-10 L73.2) (in German). JDDG 2012;10(suppl 5): S1-S31.

- Revuz JE, et al: Prevalence and factors associated with hidradenitis suppurativa: results from two case-control studies. JAAD 2008;59: 596-601.

- Jemec GB, Heidenheim M, Nielsen NH: The prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa and its potential precursor lesions. JAAD 1996;35: 191-194.

- Woodruff CM, Charlie AM, Leslie KS: Hidradenitis suppurativa: a guide for the practicing physician. Mayo Clin Proc 2015; 90: 1679-1693.

- Hunger RE, et al: Toll-like receptor 2 is highly expressed in lesions of acne inversa and colocalizes with C-type lectin receptor. BJD 2008; 158: 691-697.

- Jemec GB, Hansen U: Histology of hidradenitis suppurativa. JAAD 1996; 34: 994-999.

- Schlapbach C, et al: Expression of the IL-23/Th17 pathway in lesions of hidradenitis suppurativa. JAAD 2011; 65: 790-798.

- von Laffert M, et al: Hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa): early inflammatory events at terminal follicles and at interfollicular epidermis. Exp Dermatol 2010;19: 533-537.

- Margesson LJ, Danby FW: Hidradenitis suppurativa. Best practice and research. Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2014; 28: 1013-1027.

- Alavi A: Hidradenitis suppurativa: demystifying a chronic and debilitating disease. JAAD 2015; 73(5 suppl 1): S1-S2.

- Revicki D, et al: Impact of adalimumab treatment on health-related quality of life and other patient-reported outcomes: results from a 16-week randomized controlled trial in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. BJD 2008;158: 549-557.

- Kimball A, et al: Patients’ experiences with hidradenitis suppurativa: a qualitative study of symptoms and impacts. JAAD 2013; 68: AB57.

- Kimball AB, et al: Adalimumab for the treatment of moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a parallel randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2012;157: 846-855.

- Jemec GB: Clinical practice. Hidradenitis suppurativa. NEJM 2012;366: 158-164.

- Saunte DM, et al: Diagnostic delay in hidradenitis suppurativa is a global problem. BJD 2015;173: 1546-1549.

- Zouboulis CC, et al: Hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: criteria for diagnosis, severity assessment, classification and disease evaluation. Dermatology 2015;231: 184-190.

- Revuz J: Hidradenitis suppurativa. JEADV 2009; 23: 985-998.

- Sartorius K, et al: Objective scoring of hidradenitis suppurativa reflecting the role of tobacco smoking and obesity. BJD 2009; 161: 831-839.

- Sartorius K, et al: Suggestions for uniform outcome variables when reporting treatment effects in hidradenitis suppurativa. BJD 2003; 149: 211-213.

- Miller IM, et al: Association of metabolic syndrome and hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol 2014;150: 1273-1280.

- Tzellos T, et al: Cardiovascular disease risk factors in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BJD 2015; 173: 1142-1155.

- Schrader AM, et al: Hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective study of 846 Dutch patients to identify factors associated with disease severity. JAAD 2014; 71: 460-467.

- Boer J, Nazary M, Riis PT: The role of mechanical stress in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Clin 2016; 34: 37-43.

- Nazary M, et al: Pathogenesis and pharmacotherapy of hidradenitis suppurativa. Eur J Pharmacol 2011; 672: 1-8.

- van der Zee HH, et al: The association between hidradenitis suppurativa and Crohn’s disease: in search of the missing pathogenic link. J Invest Dermatol 2016;136: 1747-1748.

- Shavit E, et al: Psychiatric comorbidities in 3,207 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JEADV 2015;29: 371-376.

- van der Zee HH, et al: Hidradenitis suppurativa and inflammatory bowel disease: are they associated? Results of a pilot study. BJD 2010; 162: 195-197.

- Hsiao JL, et al: Hidradenitis suppurativa and concomitant pyoderma gangrenosum: a case series and literature review. Arch Dermatol 2010; 146: 1265-1270.

- Kraft JN, Searles GE: Hidradenitis suppurativa in 64 female patients: retrospective study comparing oral antibiotics and antiandrogen therapy. J Cutan Med Surg 2007; 11: 125-131.

- Jemec GB, Wendelboe P: Topical clindamycin versus systemic tetracycline in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. JAAD 1998; 39: 971-974.

- Gener G, et al: Combination therapy with clindamycin and rifampicin for hidradenitis suppurativa: a series of 116 consecutive patients. Dermatology 2009;219: 148-154.

- Kimball AB, et al: Two phase 3 trials of adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. NEJM 2016;375: 422-434.

- Boer J, Nazary M: Long-term results of acitretin therapy for hidradenitis suppurativa. Is acne inversa also a misnomer? BJD 2011; 164: 170-175.

- Hunger RE, et al: Swiss practice recommendations for the treatment of hidradenitis suppu-rativa (acne inversa). Compass Dermatol 2019; 7 (1): 8-13.

- Hunger RE, et al: Swiss Practice Recommendations for the Management of Hidradenitis Suppurativa/Acne inversa. Dermatology, 2017, 233 (2-3).

- van der Zee HH, et al: Adalimumab (anti-TNF-α) treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa ameliorates skin inflammation: an in situ and ex vivo study. BJD 2012; 166: 298-305.

- Wolk K, et al: Deficiency of IL-22 contributes to a chronic inflammatory disease: pathogenetic mechanisms in acne inversa. J Immunol 2011, 186: 1228-1239.

- Högenauer C, et al: Interdisciplinary management of immune-mediated diseases-an Austrian perspective. Journal of Gastroenterological and Hepatological Diseases 2019; 17: 108-124.

- Fimmel S, Zouboulis CC: Comorbidities of hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa). Dermatoendocrinol 2010; 2(1): 9-16.

- Sabat R, et al: Increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with acne inversa. PloS One 2012; 7(2):e31810.

- Gold DA, et al: The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAAD 2014; 70(4): 699-703.

- Deckers IE, et al: Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with hidradenitis suppurativa: results from a multicenter cross-sectional study. JAAD 2017; 76(1): 49-53.

- Shlyankevich J, et al: Hidradenitis suppurativa is a systemic disease with substantial comorbidity burden: a chart-verified case-control analysis. JAAD 2014; 71(6): 1144-1150.

- Richette P, et al: Hidradenitis suppurativa associated with spondyloarthritis – results from a multi-center national prospective study. J Rheumatol 2014; 41(3): 490-494.

- Esmann S, Jemec GB: Psychosocial impact of hidradenitis suppurativa: a qualitative study. Acta Derm Venereol 2011; 91: 328-332.

- Hurley HJ: Axillary hyperhidrosis, apocrine bromhidrosis, hidradenitis suppurativa and familial benign pemphigus: surgical approach. In: Roenigk RK, Roenigk HH, Jr, eds. Dermatologic surgery: principles and practice. 2nd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker 1996: 623-645.

- Kokolakis G, et al: Delayed Diagnosis of Hidradenitis Suppurativa and Its Effect on Patients and Healthcare System. Dermatology 2020; 236(5): 421-430.

- Kimball AB, et al: Assessing the validity, responsiveness and meaningfulness of the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response (HiSCR) as the clinical endpoint for hidradenitis suppurativa treatment. Br J Dermatol 2014; 171(6): 1434-1442.

- Kurzen H, et al: What causes hidradenitis suppurativa? Exp Dermatol 2008; 17(5): 455-456; discussion 457-472.

- Zouboulis CC, et al; European Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation Investigator Group. Development and validation of the International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score System (IHS4), a novel dynamic scoring system to assess HS severity. Br J Dermatol 2017; 177(5): 1401-1409.

- Vossen A, van der Zee HH, Prens EP: Hidradenitis suppurativa: A systematic review integrating inflammatory pathways into a cohesive pathogenic model. Front Immunol 2018; 9: 2965.

- Von Laffert M, et al: Hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: Bilocated epithelial hyperplasia with very different sequelae. BJD 2011; 164: 367-371.

- Schuch A, Absmaier-Kijak M, Volz T: Acne inversa/Hidradenitis suppurativa – Von der Pathogenese zur Therapie. Act Dermatol 2019; 45: 277-287.

- Melnik BC, et al: T helper 17 cell/regulatory T-cell imbalance in hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: The link to hair follicle dissection obesity smoking and autoimmune comorbidities. BJD 2018; 179: 260-272.

- Van der Zee HH, et al: Elevated levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-10 in hidradenitis suppurativa skin: A rationale for targeting TNF-α and IL-1β. BJD 2011; 164: 1292-1298.

- Zouboulis CC, et al: What causes hidradenitis suppurativa?-15 years after. Exp Dermatol 2020; 29: 1154-1170.

- Sabat R, et al: Hidradenitis suppurativa. Nat Rev Dis Prim 2020; 6: 18.

- Thomi R, et al: Association of Hidradenitis Suppurativa with T Helper 1/T Helper 17 Phenotypes: A Semantic Map Analysis. JAMA Dermatol 2018; 154: 592.

- Wieland CW, et al: Myeloid marker S100A8/A9 and lymphocyte marker, soluble interleukin 2 receptor: Biomarkers of hidradenitis suppurativa disease activity? Br J Dermatol 2013; 168: 1252-1258.

- 60 Saunte DML, Jemec GBE: Hidradenitis Suppurativa: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA 2017; 318: 2019-2032.

- Gierek M, et al: Hidradenitis suppurativa: Bacteriological study in surgical treatment. Postep. Dermatol Alergol 2022; 39: 1101-1105.

- Jastrząb B, et al: The Prevalence of Periodontitis and Assessment of Oral Micro-Biota in Patients with Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. J Clin Med 2022; 11: 7065.

- Ganzetti G, et al: Periodontal Disease: An Oral Manifestation of Psoriasis or an Occasional Finding? Drug Dev. Res. 2014, 75, S46-S49.

- 64 Vaienti S, et al: Lymph Node Involvement in Axillary Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Clinical, Ultrasonographic and Bacteriological Study Conducted during Radical Surgery. J Clin Med 2021; 10: 1433.

- 65 Molinelli E, et al: New Insight into the Molecular Pathomechanism and Immunomodulatory Treatments of Hidradenitis Suppurativa. Int J Mol Sci 2023; 24(9): 8428. www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/24/9/8428,(last accessed 16.10.2023)

- Brajac I, et al: Smjernice za Dijagnostiku i Liječenje Gnojnog Hidradnitisa (Hidradenitis Suppurativa) Liječ Vjesn 2017; 139: 247-253.

- Hana A, et al: Functional significance of non-neuronal acetylcholine in skin epithelia. Life Sci 2007; 80: 2214-2220.

- Ingram JR, et al. : British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for the management of hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa) 2018. British Journal of Dermatology 2019; 180 (5): 1009-1017.

- Frings VG, et al. Assessing the psychological burden of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Eur J Dermatol 2019; 29: 294-301.

- Ballard K, Shuman VL: Hidradenitis Suppurativa. [Updated 2023 Apr 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan.

- Fernandez JM, et al: Pain management modalities for hidradenitis suppurativa: a patient survey. J Dermatolog Treat 2022; 33(3): 1742-1745.

- Swissmedic: Medicinal product information, www.swissmedicinfo.ch,(last accessed 16.10.2023)

- Scala E, et al: Hidradenitis Suppurativa: Where We Are and Where We Are Going. Cells 2021, 10, 2094. www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/10/8/2094#,(last accessed 16.10.2023).

Cover picture: Dr. Thomas Brinkmeyer, wikimedia. Hurley stage II

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2023; 33(5): 6-11