Alcohol-related disorders are among the common mental disorders, with a prevalence of 7-10%. Psychotherapy and rehabilitation of alcoholics is quite promising, abstinence rates of 40-50% are achievable. Most therapies are eclectic. Behavioral and cognitive therapies, relapse prevention, social skills training, motivational therapies, and marital and family therapy in particular have good evidence. Relatively few medications have proven effective as “cessation” or anticraving agents for alcohol dependence. Evidence-based agents include acamprosate and the opioid antagonist naltrexone. Another opioid antagonist, nalmefene, will soon be introduced as an “as needed” approach to drinking reduction.

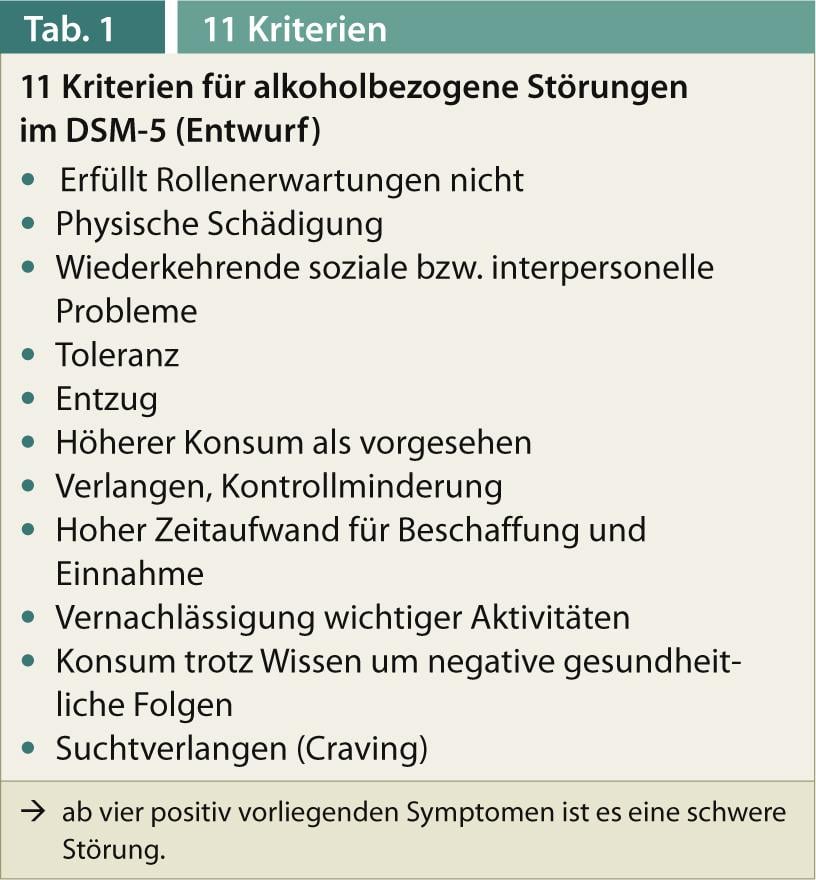

Alcohol abuse and dependence are common mental disorders. In the ICD-10 of the WHO, as previously in the DSM-IV of the American Psychiatric Association, a distinction is made between alcohol abuse (ICD-10: harmful use) and alcohol dependence. Alcohol abuse is essentially characterized by physical, psychological, and social sequelae (only in DSM-IV), whereas a diagnosis of dependence is a cluster of biological, psychological, and social symptoms (6 in ICD-10, 7 in DSM-IV), three of which must be met in each case [1, 2]. In the newly published DSM-5, the categorical distinction between abuse and dependence is abandoned in favor of a dimensional concept, i.e., classification is based on severity (positive symptoms present) (e.g., severe disorder from 4 of the maximum 11 symptoms, Tab. 1). The ICD-11, which is under revision, will retain the distinction between abuse and dependence.

Epidemiology in Europe

The prevalence for alcohol-related disorders is 7-10% in most Western countries [1]. Per capita consumption in Germany has been declining for years and most recently for 2011 was 9.6 l per capita, including 107 l of beer, 20.2 l of wine, 4.1 l of sparkling wine and 5.4 l of spirits. Drinking rates in Austria are similar, as are those in Switzerland. If we follow the 2009 Epidemiological Survey on Addiction, which surveyed 18- to 64-year-olds, the percentage of adults who are abstinent for life is exceptionally small, only 2.9%, 7.3% for the last twelve months.

Risky consumption of alcohol, defined as drinking more than 24 g of pure alcohol per day for men and 12 g for women, was present in 16.5% of the total population (men 18.5%, women 14.3%). According to this calculation, there would be a total of 8.5 million people in Germany with alcohol consumption that tends to be hazardous to health. The DSM-IV diagnosis of abuse was met by 3.8% of the population (men 6.4%, women 1.2%), representing 2 million individuals. The DSM-IV diagnosis of “dependence” was met by 2.4% of the population (men 3.4%, women 1.4%). Extrapolated, this would be 1.3 million people.

Alcohol-related deaths in Europe are estimated at 137 000 per year, including 39 000 cases of liver cirrhosis.

Alcohol dependence therapy

According to Kiefer and Mann, the treatment goals for alcohol dependence can be arranged hierarchically [3]:

- Treatment of secondary and concomitant diseases

- Promoting insight into illness and motivation to change

- Improvement of the psychosocial situation

- Permanent abstinence

- Reasonable Quality of Life.

For Germany, there is currently no valid S-3 guideline for the treatment of alcoholism, and the former AWMF S-2 guideline on post-acute treatment of alcohol-related disorders [4, 24] is no longer valid. A new S-3 guideline is expected to be established in 2014. For the field of pharmacotherapy, there are some recent Cochrane analyses [5, 6], and for the rest, there are numerous international treatment guidelines.

Important meta-analyses and reviews have been published, for example, by Miller and Hester ([7], review of 381 studies). Other important work has been presented by the Health Technology Board for Scotland and the Cochrane Collaboration, as well as the Swedish Council and Technology Assessment and Health Care [3].

What therapy goals do you set in the first place?

In principle, treatment recommendations for harmful alcohol use and dependence, as with other diseases, are based on the severity of the disease and the primary treatment goals. For a long time, especially in the American region, (preferably lifelong) alcohol abstinence was an ideal treatment goal that could hardly be questioned, but for which many patients are not sufficiently motivated. Analogous to other addictions (e.g., opiate addiction), however, so-called harm reduction strategies are also legitimate, which can also include a reduction in drinking quantity, at least as a first step. This is especially true for milder dependency disorders that have not been entrenched for long.

Motivation very important for therapy success

One of the key concepts is that of motivational treatment. Motivation is a dynamic process that is not only a prerequisite for therapy, but can also be developed in it. The patient should first be motivated to accept his illness (insight into the illness), then to take therapeutic measures and finally to achieve the agreed therapy goals.

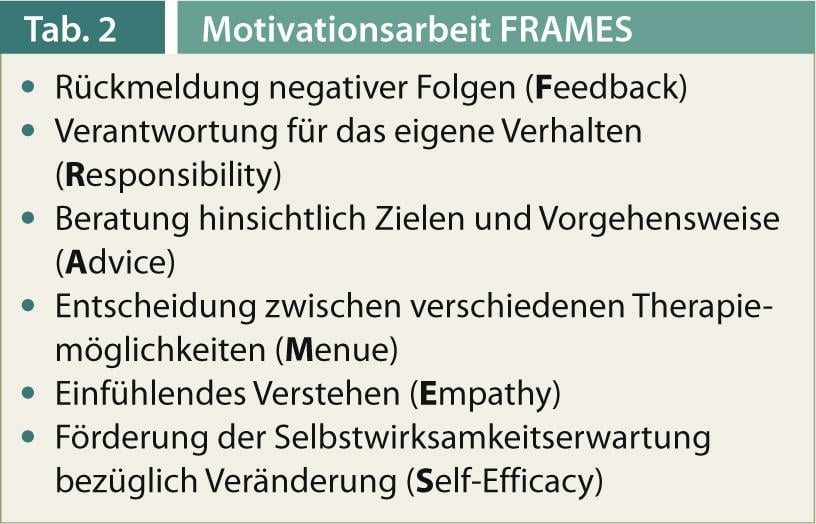

The so-called motivational interviewing ( [23]) has gained great importance. Characteristics of motivational interviewing are the empathic basic attitude with renunciation of a confrontational approach, the promotion of discrepancy perception and, above all, the willingness to change, the building of trust in self-efficacy, and the agreement of jointly developed treatment goals. Motivational interviewing techniques include asking open-ended questions without implied judgment, reflective listening, positive feedback, and structured summarization [1, 3].

In addition to inpatient treatment, numerous outpatient therapies are now offered for alcohol dependence.

The recommendation agreement “Outpatient Rehabilitation Addiction” of the health and pension insurance providers lists the following criteria as prerequisites for the implementation of outpatient withdrawal therapy:

- A “relatively intact social environment”

- Willingness and ability to abstain from addictive substances

- Ability and motivation to actively participate

- Regular participation

- Adherence to the therapy plan

- Sufficient professional integration

- Stable housing situation.

- The exclusion criteria mentioned are:

- Severe physical and/or neurological sequelae

- Psychiatric treatments that require inpatient care

- Lack of social integration

- Lack of readiness for treatment

- The need for removal from the pathogenic milieu.

Miller and Sanchez (1993) have summarized basic features of motivational work under the acronym “FRAMES” (Tab. 2, [1]). Motivation depends on the severity of the addiction disease, the severity of the secondary disorder, depressive moods, but also “life events”, e.g. negative life events in the last months [8].

Psychotherapy of alcohol dependence

Purely somatic detoxification in alcoholics is not very effective if it does not also include (psycho)therapeutic elements [21, 22]. In German-speaking countries, the term “qualified withdrawal treatment” has become established for this [3]. Without motivational elements, purely somatic detoxification has high relapse rates and usually leads to revolving door treatment.

The actual rehabilitation or withdrawal is about learning and practicing new behaviors that are necessary to achieve the most permanent change in alcohol consumption and abstinence. Furthermore, the treatment of possible physical and psychiatric concomitant and underlying diseases, an improvement of the patient’s social environment and, if necessary, the reintegration into professional and family life are important. The duration of withdrawal treatments, at least in an inpatient setting, has been significantly reduced in recent years, also for cost reasons. Several years ago, the German Pension Insurance Association (Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund), as the provider of most rehabilitation facilities, launched a program for quality improvement and quality management in addiction clinics [9].

Therapeutic strategies used include cognitive-behavioral therapies [11], behavioral and related psychotherapies including contingency management, motivational enhancement, couples and family therapies, and, especially in the U.S., psychotherapies based on the twelve steps of Alcoholics Anonymous. Depth psychological and, increasingly, mindfulness-based therapies are also used [1, 10]. Psychoeducation is also used a lot, but is rather moderately evidence-based.

Metaanalytical state of the research

There are hardly any randomized therapy studies available from German-speaking countries. Internationally, a whole series of meta-analyses have been performed. For example, the Mesa Grande project [11]. According to this, especially “brief-intervention” strategies, therapies to improve social skills (“social-skills-training”), so-called “community-reinforcement-approaches”, behavior therapy, behavior therapy-oriented family and marriage therapy as well as various forms of “case-management” are well documented. Important meta-analyses have been presented, for example, by Hester and Miller and Miller and Wilbourne [11, 12]. In general, good evidence was shown for behavioral and also cognitive therapies, social skills training, relapse prevention, motivational enhancement, and couples and family therapy. Other complementary elements of addiction therapy for alcohol abusers include measures that help improve stress management or minimize stress, namely relaxation techniques and therapy elements that improve self-image and strengthen self-esteem functions.

“Harm-reduction” strategies have gained great prominence in the addiction field as a whole and have been studied, at least for non-dependent problem drinkers. At least in the short term, abstinence is not achievable for all alcoholic patients. Concepts for reducing drinking quantities in the sense of an open-target approach are perfectly justifiable and legitimate. With a broadening of the therapeutic tableau, more patients should also be responsive.

For example, Klingemann et al. show that the focus on abstinence-only treatment goals and the acceptance of the “loss of control” concept is not shared by many patients [13].

Individual forms of therapy

Behavioral and cognitive therapies: These are based on the assumption that maladaptive behavior, such as addictive behavior, can be learned and, in some cases, unlearned. Important elements here include teaching coping strategies, social skills training, occasionally exposure procedures, coin or reward strategies, and relapse prevention.

Analytic depth psychological psychotherapies: These are less well established for alcohol dependence. Here, addiction is primarily understood as part of a deficient personality development (ego deficit with lack of frustration tolerance and disturbance of affect control) [2]:

- Increased sensitivity for own and other people’s feelings

- Improvement of frustration tolerance and affect control

- Improvement of self-esteem

- Change of object representations by correction of the ideal parent image

- Addiction as an increased attempt to adapt on the basis of a primarily disturbed personality development.

Relapse prevention and management: In contrast, elements of relapse prevention and management are of greater importance. Appropriate therapy components trace back to Marlatt and Gordon’s social cognitive model of recidivism [14]. The goal is to sensitize the alcoholic for dealing with relapse-critical situations, to teach him appropriate coping strategies and to work out with him how to deal with high-risk situations. Further, there are procedures for building self-control and self-management.

Mindfulness-based therapies: Mindfulness-based therapies have gained greater prominence in the addiction field in recent years [15]. Far Eastern attitudes to life and elements of mindfulness meditation have been incorporated into therapeutic concepts here. The alcoholic should be moved to active, self-determined action [12]. A mindfulness-based treatment module for relapse prevention with a total of eight therapy units is available for German-speaking countries [15].

Overall, abstinence rates of 40-50% are quite achievable with intensive psycho- and sociotherapeutic treatments for alcoholics [1, 2].

Pharmacotherapeutic relapse prophylaxis: here, despite intensive basic research efforts, relatively few drugs are clinically available to date [16]. Acamprosate, a substance acting predominantly via glutamatergic neurons without other psychotropic effects, has been shown to be effective in a series of placebo-controlled double-blind trials over three to max. twelve months have been examined.

A recent Cochrane analysis showed that patients treated with acamprosate (2 g/d, corresponding to 3×2 tbl.) had a slightly higher abstinence rate compared with placebo-treated patients, although there was considerable heterogeneity in the overall findings [5]. Tolerability was generally good, but diarrhea was significantly more common in the acamprosate group than in the placebo group.

In contrast, in the Cochrane analysis, the opioid antagonist naltrexone showed more of an effect in terms of reducing drinking, and less in terms of abstinence rates [6]. Naltrexone oral 50 mg blocks the µ-opioid receptor for 24 hr, reducing positive reinforcing euphoric effects of alcohol. Side effects were mainly nausea and gastrointestinal effects. Functionally relevant variants at the µ-opioid receptor may have significance for the efficacy of naltrexone [17].

Another interesting meta-analysis by Maisel et al. [18] replicated the findings of Rösner et al. [5, 6] largely.

A relatively new approach in several respects is another opioid antagonist called nalmefene, which recently received approval from the European Medicines Agency in London (EMA) for the treatment of alcohol dependence and is about to be launched in Austria. Like naltrexone, nalmefene (20 mg/d) is an antagonist at the µ-opioid receptor, but it is also a partial agonist at the kappa-opioid receptor, so it has a slightly different mechanism of action. In a series of studies, nalmefene was shown to achieve significant reductions in drinking when used “as needed,” where the patient could decide whether or not to take the drug [1, 19]. Abstinence was not an end-goal criterion in these pharmaco-studies. Thus, nalmefene would represent a new pharmacotherapeutic approach in the treatment of alcohol dependence as part of a so-called “harm-reduction” strategy.

Interesting is also the approach with the GABA-B agonist baclofen, a drug used in neurology, which according to a self-report of the recently deceased French physician Ameisen is used in sometimes very high dosages as an anticraving substance. The database to date is still limited, but a number of broader studies on this are ongoing [1]. Interestingly, many supporters of this therapy have organized themselves in their own Internet forum (alkohol-und-baclofen-forum.de).

Literature:

- Soyka M: Update alcohol dependence. Bremen: Unimed Verlag 2013.

- Soyka M, Küfner H: Alcoholism – Abuse and Dependence, 6th edition. Stuttgart: Thieme 2008.

- Kiefer F, Mann K: Evidence-based treatment of alcohol dependence. Neurologist 2007; 78: 1321-1331.

- Geyer D, et al: AWMF guideline: post-acute treatment of alcohol-related disorders. Addiction 2006; 52: 8-34.

- Rösner S, et al: Acamprosate for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010a; 9 (CD004332).

- Rösner S, et al: Opioid antagonists for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010b; 12: CD001867.

- Miller WR, et al: Wat works? A summary of alcohol treatment outcome research, in: Hester RK, Miller WR (eds.): Handbook of alcoholism treatment approaches: effective alternatives, 3rd ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon 2003; 13-63.

- Finney JW, Moos RH: Entering treatment for alcohol abuse: a stress and coping model. Addiction 1995; 90: 1223-1240.

- Magill M, Ray LA: Cognitive-behavioral treatment with adult alcohol and illicit drug users: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trails. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2009; 70: 516-527.

- Berglund M, et al: Treating Alcohol and Drug Abuse. An Evidence Based Review. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH 2003.

- Miller WR, Wilbourne PL: Mesa Grande: a methodological analysis of clinical trails of treatments for alcohol use disorders. Addiction 2002; 97: 265-277.

- Hester RK, Miller WR: Alcohol Treatment Approaches. Boston: Allyn&Bacon 1995; 148-159.

- Klingemann H, et al: Drinking Episodes during Abstinence-oriented Inpatient Treatment: Dual perspectives of patients and therapists – A Qualitative Analysis. Alcohol Alcohol 2013; 48: 322-328.

- Marallt GA, Gordon JR: Relapse prevention. New York: Guilford 1985.

- Bowen S, et al: Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance dependence. The MBRP program. Weinheim Basel: Beltz 2012.

- Spanagel R, Vengeliene V: New Pharmacological Treatment Strategies for Relapse Prevention. Curr Topics Behav Neurosci 2013; 13: 583-609.

- Anton RF, et al: An evaluation of mu-opioid receptor (OPRM1) as a predictor of naltrexone response in the treatment of alcohol dependence: results from the Combined Pharmactherapies and Behavioral Interventions for Alcohol Dependence (COMBINE) study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008; 65: 135-144.

- Maisel NC, et al: Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: when are these medications most helpful? Addiction 2012; 108: 275-293.

- Mann K, et al: Extending the Treatment Options in Alcohol Dependence: A Randomized Controlled Study of As-Needed Nalmefene. Biol Psychiatry 2013 (in press).

- Mann K, Kiefer F: Evidence-based treatment of alcohol dependence. Neurologist 2007; 11: 1321-1331.

- Brueck G, Mann K: Alcoholism-specific psychotherapy: manual with treatment modules. Deutscher Ärzteverlag, Cologne 2006.

- Loeber S, Mann K: Development of evidence-based psychotherapy for alcoholism-a review. Neurologist 2006; 5: 558-566.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S: Motivational interviewing. New York: Guilford Press 1991.

- Schmidt P, et al: Evidence-based guidelines in the inpatient treatment of alcohol-dependent patients: the guideline program of the German Pension Insurance Association. Suchtmed 2007; 9: 53-64.