Exercise therapy, in addition to optimal drug therapy, is an adjuvant method for treating patients with chronic heart failure. Structured training can achieve relevant improvement in performance and limiting symptomatology (IA recommendation). Exercise therapy is cost-effective by reducing hospitalizations and is recommended (IA). Training therapy should be individualized according to a performance test. Endurance training forms the basis, supplemented by structured strength and breathing training. A structured exercise program should form the basis of a physically active lifestyle for patients with heart failure.

The prevalence of heart failure as a result of various cardiac diseases is increasing. Currently, about 1-2% of all adults are affected, with a prevalence of more than 10% in those over 70 years of age. Exertional dyspnea and intolerance of performance in everyday life limit the quality of life of those affected, an increase in doctor consultations and hospital stays as well as rising costs in the health care system are the consequences. Despite the medicinal and apparative treatment options, an improvement of the symptoms is not always easy to achieve. Exercise therapy is an adjunctive form of therapy that can help improve exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with heart failure [1].

Positive effects through physical training

Positive effects of physical activity on cardiovascular health have been known since the 1950s. In patients with coronary artery disease without signs of heart failure, physical activity to improve prognosis has been established for many years. In contrast, physical activity has long been considered contraindicated in patients with heart failure. The background for this was the fear that activity could promote the progression of the underlying disease. However, since the 1990s, there have been many studies demonstrating improvement in cardiorespiratory fitness and clinical symptoms even in patients with heart failure [2].

Physical exercise can produce beneficial effects in patients with heart failure through several mechanisms. At the endothelium, increased blood flow leads to pulsatile vessel wall elongation (“shear stress”), which increases the bioavailability of vasodilator nitrogen via activation of eNOS (“endothelial nitric oxide synthase”). This improves perfusion and oxygenation of both the myocardium and peripheral muscles. Regular exercise stimuli have a beneficial effect on the catabolic metabolism and peripheral myopathy that develop in the course of heart failure [3]. Thus, regular physical training counteracts cardiac cachexia, which is an independent predictor of mortality [4]. In addition to the relevant improvement in performance and limiting symptoms, physical training can also reduce the rate of hospitalizations for decompensated heart failure, which leads to a decisive cost saving in the health care system. For this reason, current guidelines recommend IA for both indications [1]. The fact that no clear mortality benefit from exercise therapy has been shown so far may be due to the often long-term lack of compliance of patients with heart failure [5,6].

Phases of training therapy

At many centers, exercise therapy is used for adjunctive treatment of patients with stable heart failure. In acutely decompensated and hospitalized patients, mobilization already takes place during the inpatient stay (phase I). Subsequently, exercise therapy can be implemented as part of a multidisciplinary rehabilitation program (phase II), which also treats patients’ comorbidities (e.g., medication management of cardiovascular risk factors, smoking cessation, nutritional counseling, psychological counseling) [1]. As a rule, these programs are offered for a limited period of three to six months; in Switzerland, the costs are covered by health insurance companies. The goal is for patients to be able to continue their physical activity independently after this time in order to maintain long-term positive effects (phase III). In phase III, training can also be performed in regional cardiac groups (www.swissheart.ch).

Movement-based training therapy in phase II

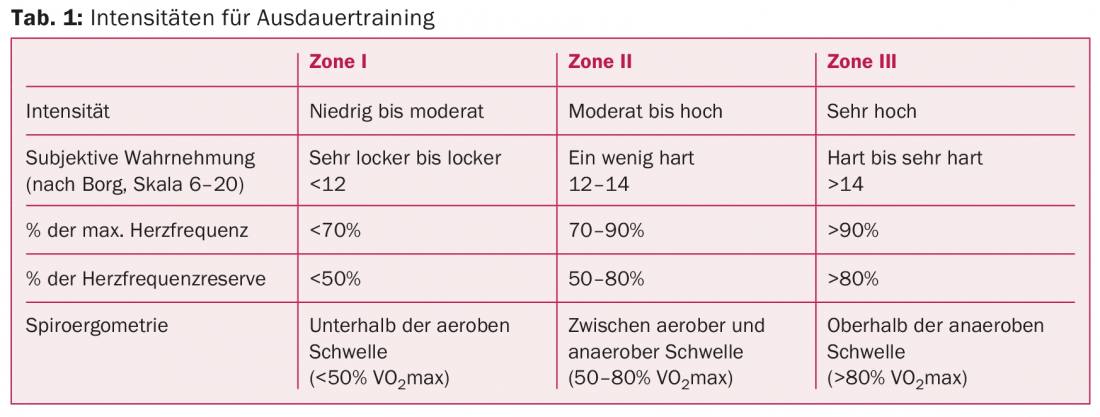

A supervised and structured exercise program can be implemented in all stages of chronic stable heart failure. A performance test at baseline is used to assess cardiorespiratory fitness and estimate cardiovascular risk. The gold standard is spiroergometry to determine maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) and ventilatory thresholds. Depending on this, the individual training zones for endurance training are determined. Furthermore, the subjective load intensity is also recorded using the Borg scale and included in the training control (Tab. 1). In addition to endurance training, strength and respiratory muscle training are also performed [7].

Endurance training

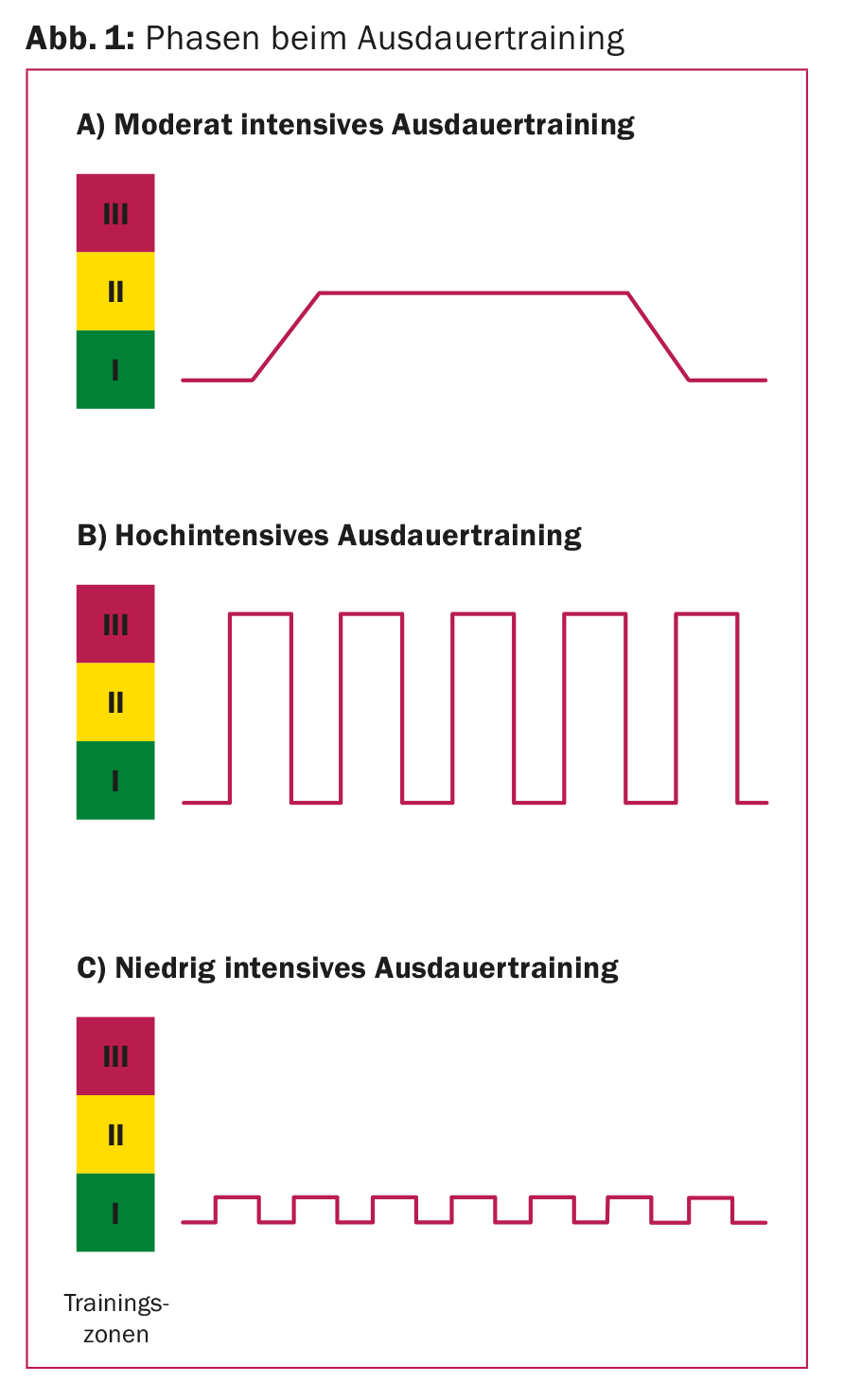

Aerobic endurance training is the longest established form of training, usually moderate continuous training is performed in zone II (40-70% of previously determined VO2max). After a short warm-up phase, a load with constant load intensity is applied. The aim is a continuous load over 20-30 minutes (Fig. 1A). Initially, training is performed in the lower range of zone II and with short load durations. With improvement of the training condition, the load intensity is increased in the course. Continuous moderate endurance training is performed two to three times a week.

In addition to continuous endurance training, high-intensity interval training has become increasingly established in the training therapy of heart failure in recent years, as a higher increase in performance and a more significant improvement in symptoms can be achieved through a modified training protocol [8,9]. Such training is performed once a week as a supplement to continuous moderate training. In this process, short, more intensive load phases alternate with active “recovery phases” in which training takes place at a lower load level. The high-intensity interval is usually in zone III, and the “recovery” phases are at low load levels (zone I) (Fig. 1B).

In very weak patients with severe cardiorespiratory limitation, low-intensity interval training can be performed analogously, alternating short periods of exertion of, for example, 30 seconds at a low, tolerated exertion level in zone I with rest periods. Load intensities and step duration must be modified individually in each case (Fig. 1C).

Strength training

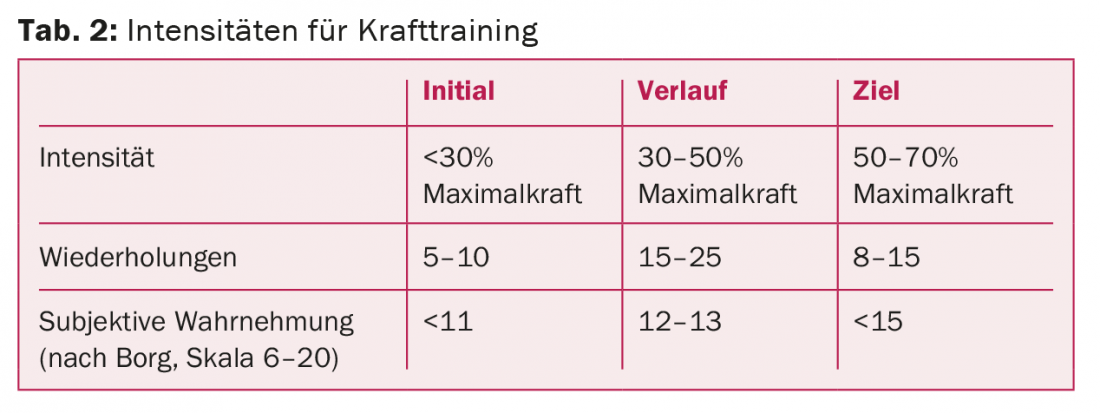

Strength training is performed as a complementary training modality to endurance training. With careful management and individual adaptation of training protocols and intensities to the maximum possible repetitions, no adverse cardiac effects of structured strength training have been demonstrated [10]. In order to ensure proper implementation, it is necessary that a step-by-step build-up takes place. First, coordination and sequence of training sessions are practiced without load. After that, the intensity is gradually increased. Initially, low-intensity strength endurance training with a high number of repetitions is performed – only when patients are familiar with the sequence and performance of the exercises is higher-intensity hypertrophy training aimed at building muscle performed (Tab. 2) . Strength training should be performed two to three times a week [7].

Breathing training

Respiratory muscle weakness has been described in patients with heart failure [11]. Even though endurance and strength training lead to increased work of breathing and thus stress on the respiratory support muscles, it has been shown that targeted training of the respiratory muscles can help improve exercise tolerance and dyspnea symptoms, especially in patients with established weakness of the respiratory muscles. Respiratory muscle training should be done several times a week in addition to endurance training and strength training and can be done with the help of specially designed equipment.

Literature:

- McMurray JJ, et al: ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: European heart J 2012; 33(14): 1787-1847.

- Hambrecht R, et al: Physical training in patients with stable chronic heart failure: effects on cardiorespiratory fitness and ultrastructural abnormalities of leg muscles. J of the Am College of Cardiology 1995; 25(6): 1239-1249.

- Middlekauff HR: Making the case for skeletal myopathy as the major limitation of exercise capacity in heart failure. Circulation heart failure 2010; 3(4): 537-546.

- Anker SD, et al: Wasting as independent risk factor for mortality in chronic heart failure. Lancet 1997; 349(9058): 1050-1053.

- O’Connor CM, et al: Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009; 301(14): 1439-1450.

- Taylor RS, et al: Exercise-based rehabilitation for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;4:CD003331.

- Piepoli MF, et al: Exercise training in heart failure: from theory to practice. A consensus document of the Heart Failure Association and the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Europ J heart failure 2011; 13(4): 347-357.

- Wisloff U, et al: Superior cardiovascular effect of aerobic interval training versus moderate continuous training in heart failure patients: a randomized study. Circulation 2007; 115(24): 3086-3094.

- Meyer P, et al: High-intensity aerobic interval exercise in chronic heart failure. Current heart failure reports 2013; 10(2): 130-138.

- Spruit MA, et al: Effects of moderate-to-high intensity resistance training in patients with chronic heart failure. Heart 2009; 95(17): 1399-1408.

- Ribeiro JP, et al: Respiratory muscle function and exercise intolerance in heart failure. Current heart failure reports 2009; 6(2): 95-101.

CARDIOVASC 2015; 14(2): 6-9