If shortness of breath occurs during exercise, exercise-induced asthma should always be considered. Typical symptoms of exercise-induced asthma include whistling breathing, shortness of breath, and/or coughing during or after exercise. Diagnostically, spirometry and direct and indirect bronchoprovocation tests are used. Therapy is based on rapid-acting beta-sympathomimetics, and on inhaled steroids or leukotriene antagonists for frequent symptoms. In the case of licensed athletes, the doping list must be taken into account during therapy.

When we engage in physical activity, various adjustments in the cardiovascular and respiratory systems are necessary to adapt to the new muscular needs. Among other things, there is an increase in the respiratory minute volume and cardiac output in order to supply the muscles with sufficient operating materials (oxygen, glucose). At maximum load, the cardiac output reaches its limits in healthy individuals, the supply to the muscle reaches a limit and it fatigues, so that the load has to be terminated sooner or later [1]. In asthmatics, on the other hand, the system is limited much earlier by a reduced respiratory minute volume. Oxygen supply is depleted, and the stress limit is significantly lowered [2].

Asthma is a common disease. In Switzerland, about 7% of the population is affected to a greater or lesser extent.

Definition of asthma and effort asthma

Bronchial asthma is defined as a chronic inflammatory airway disease with the following two additional features, both of which must be present [3]:

- Wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, or prolonged variable cough.

and

- A variable obstruction of the airways.

Most asthmatics suffer from both chronic cough and discomfort on exertion.

If symptoms occur only during exercise (i.e., the cough is absent), the condition is referred to as “exercise-induced asthma” (EIA). Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction (EIB) is a special form of EIB that manifests itself clinically in a similar way, but with a different form of inflammation in the airways.

Cough-variant asthma” is the term used when there is only a cough and patients do not suffer from any discomfort on exertion.

Pathophysiology

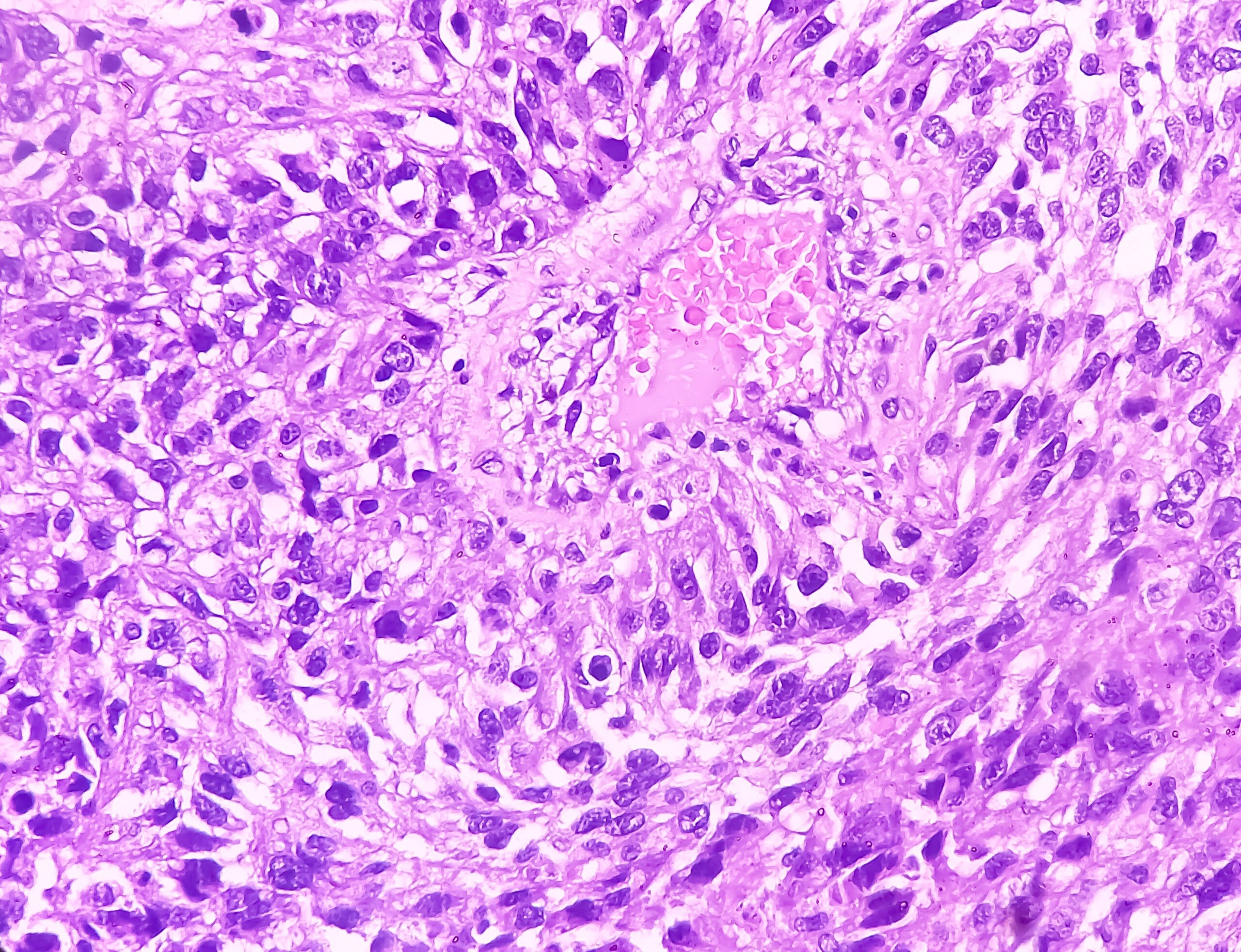

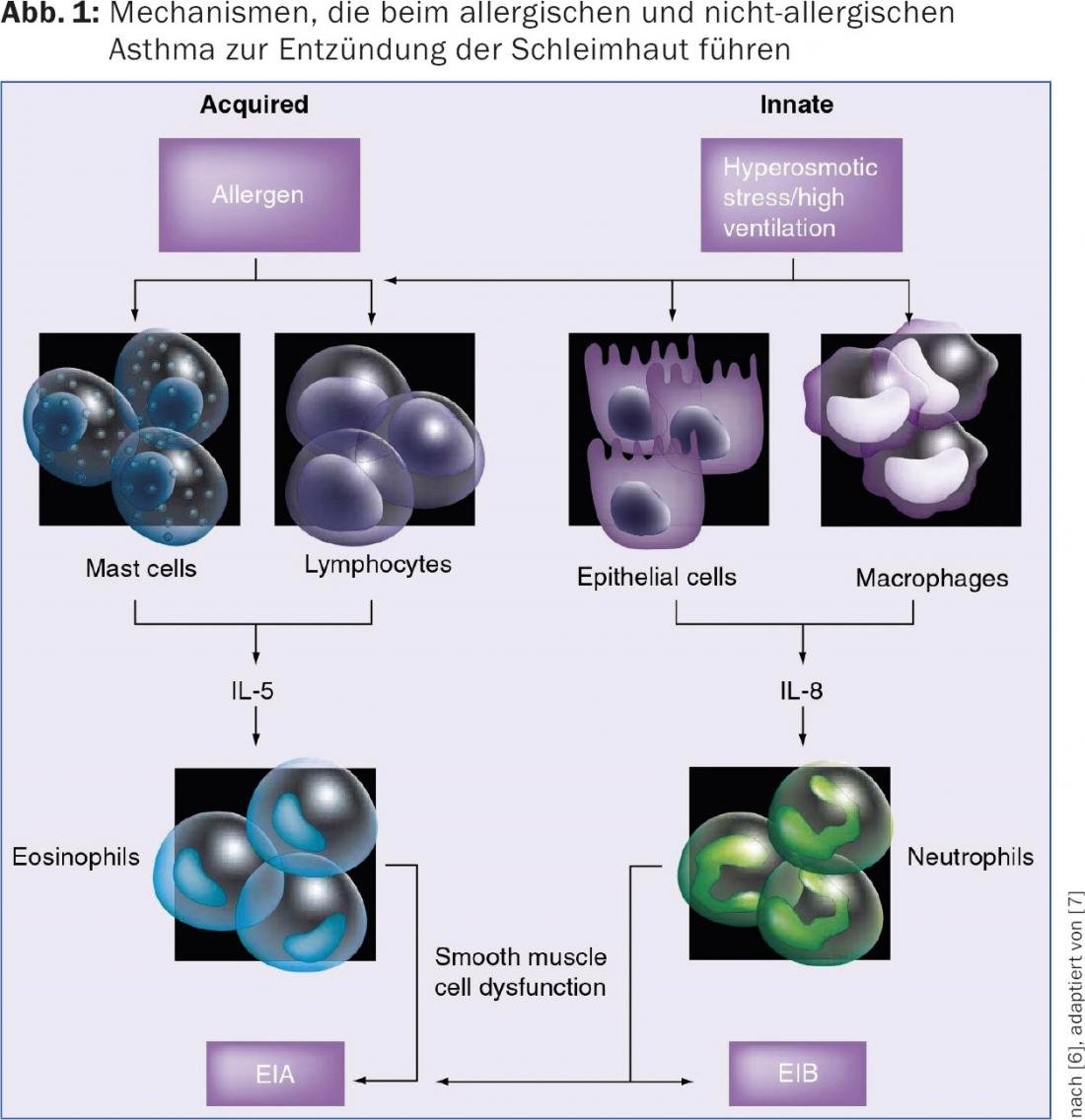

In allergic patients, contact with the allergen causes an overreaction of the immune system, which leads to IL-5-mediated eosinophilic inflammation of the bronchial mucosa [4]. The inflammation causes the chronic cough, which typically also produces clear or white secretions. Further contact with the allergen, as well as non-specific stimuli such as cold or dry air, results in smooth muscle activation and bronchospasm. Especially during sports, people practically always breathe through the mouth, so that the protective effect of the upper airways is eliminated. The air is not heated and not cleaned. Especially in cold weather, very dry and cold air enters the bronchial tubes in this way, causing irritation and discomfort without a classic allergic reaction. In addition, when breathing by mouth, the air is not cleared of the medium and large particles, which is otherwise done by the nose. This leads to additional irritation of the mucous membrane. These mechanisms can also lead to inflammation and swelling of the mucosa with subsequent bronchospasm in non-allergy sufferers via irritation of the mucosa. In contrast to allergy, neutrophilic inflammation is found histologically in the bronchi, which is triggered by macrophages and IL-8 [5,6]. In this case, the term “Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction” or “Exercise-Induced Bronchospasm” (EIB) is used (Fig. 1).

Clinic

Classically, shortness of breath and a whistling breathing sound occur during exertion. The whistling is in expiration if you listen closely. Patients, however, usually do not perceive it that way themselves.

In patients with allergic asthma (including EIA), the symptoms depend on the air concentration of the corresponding allergens. So we see an association here with the seasonal pollen count. The discomfort occurs quickly after or immediately at the start of exercise and is usually severe, so that they have to interrupt the sporting activity. However, shortness of breath also occurs during even mild exertion in everyday life, such as when climbing stairs or walking uphill or running hurriedly to the train [3,8].

In addition, patients with allergic asthma practically always also suffer from a chronic irritable cough. The only exception is exercise-induced asthma (EIA). The cough is particularly troublesome at night and not infrequently produces some viscous, glassy to white secretion in the morning that must be coughed up.

In performance asthmatics without allergy (EIB), the complaints only appear in the course of the load, i.e. after about 10 to 15 min. occur, are often very disturbing, but do not necessarily lead to load termination. A “running through” phenomenon may occur – i.e. the complaints may improve even despite further stress. The performance is nevertheless limited. In addition to shortness of breath, cough is also common as an asthma correlate. However, the cough may occur after the load has ceased [3,9].

In EIB, the symptoms are triggered by non-specific stimuli, such as cold or very dry air. Thus, winter athletes (especially cross-country skiers) are affected significantly more often than other athletes [10]. In addition, the vibrations in the airways that occur during racing seem to further provoke the asthmatic reaction. However, very warm air or high concentrations of ozone in the air can also cause irritation and inflammation of the mucous membrane. Especially with rapid increase of ventilation (sprints, stop-and-go sports) the load is particularly high even in summer [11].

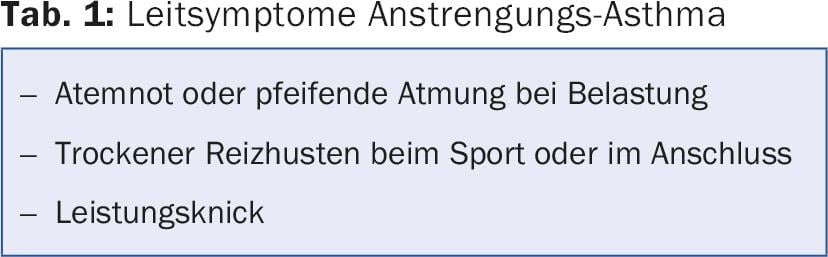

Especially with better trained athletes, there is also the possibility that no physical complaints occur at all. The performance asthma then only leads to a limitation of performance and manifests itself in a performance kink or lack of progress despite structured training (Tab. 1).

Diagnostics

According to the definition, the diagnosis of “bronchial asthma” can be made when there is a typical clinical manifestation in combination with the typical pulmonary functional changes. This is true for classical allergic asthma as well as for the special forms [3].

Therefore, the occurrence, frequency, course, and intensity of the attacks of dyspnea should be determined primarily by anamnesis. The appearance and quality of the cough should also be assessed to obtain the best possible picture of the symptoms. Both coughing during exercise and afterwards can be groundbreaking. The precise recording of the symptoms later facilitates the choice of the therapeutic agents used.

The apparative diagnosis of suspected performance-related asthma is based on the diagnosis of classical bronchial asthma [12,13].

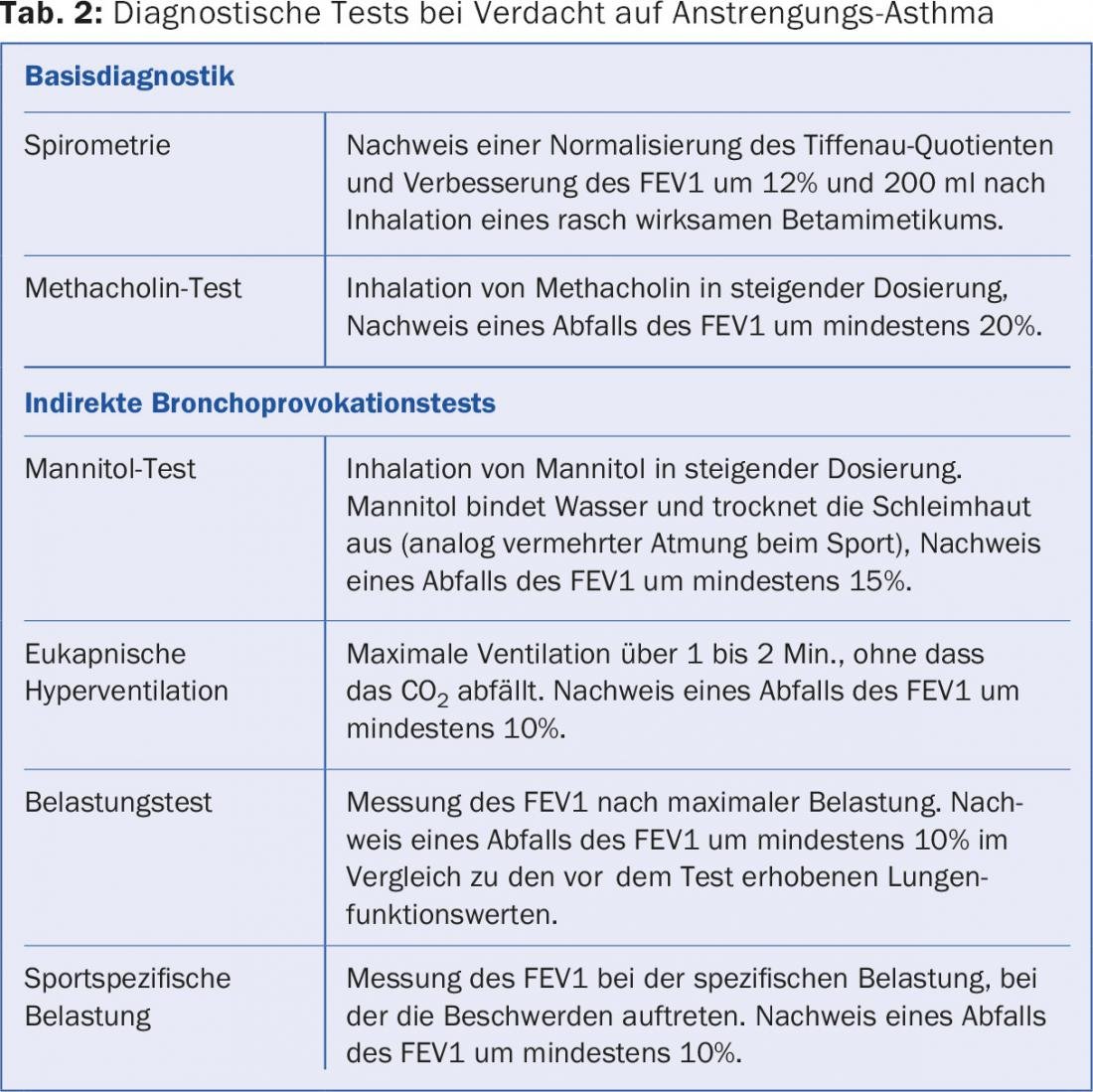

Primary examination is spirometry. If an obstruction is found here (Tiffenau quotient <70%), a positive reversibility test can already provide the diagnosis. For this to occur, inhalation of a rapid-acting beta-sympathomimetic (salbutamol, fenoterol, albuterol) must normalize the Tiffenau quotient and improve FEV1 by at least 200 ml and 12%.

If spirometry is already normal on the first test, bronchoprovocation tests are used. The most common method is bronchoprovocation with methacholine. It is a direct stimulation of receptors on bronchial smooth muscle cells, resulting in activation and contraction in asthmatics. This bronchial obstruction can be detected spirometrically and provides the diagnosis. However, patients with EIA often do not show positive results here, so that indirect provocation tests should be used.

Indirect tests simulate bronchial mucosal stress due to increased ventilation [14]. In the mannitol test, for example, the way this works is that the substance (large sugar molecule) withdraws fluid from the mucosa, causing the dehydration that would otherwise be triggered by increased ventilation. Here, too, the obstruction is measured using a spirometer [15]. The methods and limits can be found in Table 2.

Differential diagnosis

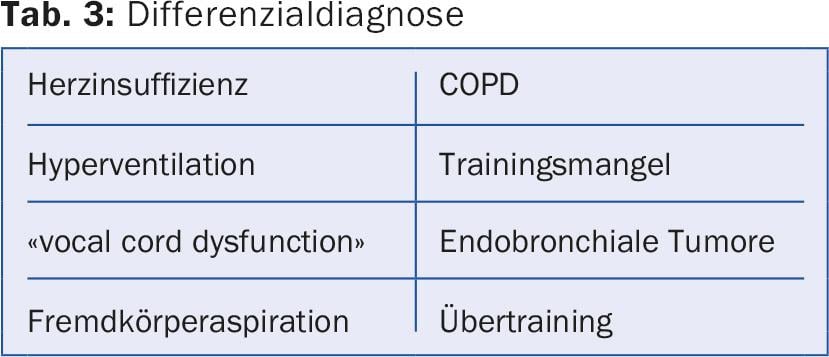

First and foremost, cardiac diseases and COPD should be considered, especially in elderly patients and smokers. The latter can already be detected or ruled out in the pulmonary functional tests that are performed as a baseline diagnostic for asthma (persistent obstruction after inhalation of a rapid-acting beta sympathomimetic).

The differential diagnosis should also include pulmonary embolism. “Trivial causes” such as obesity, lack of exercise, or primary hyperventilation should also be considered. Rare causes include “vocal cord dysfunction,” foreign body aspiration, or endobronchial stenosis or tumors [6,16].

In ambitious amateurs and in athletes, last but not least, overtraining should be considered as a cause of exertional dyspnea (table 3) [17].

Therapy

All patients with exertional asthma should take into account the external circumstances for their training. Thus, intensive sessions in very cold or very warm temperatures should be avoided. Likewise, if pollen allergy is known, pollen concentration should be queried prior to training sessions (www.pollenundallergie.ch). When pollen levels are high, outdoor sports should be avoided, if possible, and alternative exercise methods should be used [5].

Good preparation can significantly reduce symptoms. A warm-up period of about 15 minutes is recommended, with a slow increase in power and ventilation. Slow adaptation to increased breathing succeeds in exerting a less severe stimulus on the mucosa, so that the bronchoconstrictive reaction is less severe or can be avoided altogether [18].

Drug therapy for exercise-induced asthma generally does not deviate from the general recommendations for bronchial asthma. The GINA guidelines [5] are authoritative.

The basis is the use of fast-acting beta-sympathomimetics (salbutamol, fenoterol), which should be used 5 minutes before exercise in case of symptoms and also as a preventive measure during sports. The effect lasts for about three to four hours, so repetitive inhalation is not necessary in most cases.

If symptoms occur more than twice a week, or if on-demand inhalation is used more than twice a week before or during exercise, basic therapy for bronchial inflammation should also be used. Topical steroids (budenoside, fluticasone, ciclesonide) or leukotriene antagonists (montelukast, zafirlukast) are primarily available for this purpose [19].

Experience has shown that the primary recommendation is the use of low to medium doses of inhaled steroids (see GINA guidelines for dosage). In the absence of improvement, a switch to a leukotriene antagonist should be considered before extending therapy. Studies showed no clear superiority for one substance or the other.

If there is no response to monotherapy, combination therapy is used, with the combination of topical steroid and long-acting beta-sympathomimetic being used more frequently here, mainly for practical reasons. If symptoms persist, a combination of all three medications may also be prescribed as basic therapy.

In patients with mild EIB, the additional administration of fish oil may contribute to better control (omega-3 fatty acids 500 mg 2× daily).

Its use should be seen as a supplement to the above therapy, especially for athletes who train frequently [20]. The goal of asthma therapy is a symptom-free patient with as little medication as possible.

Special case competitive sports

For athletes participating in national or international competitions (generally all licensed athletes), the regulations of the Anti-Doping Agency (WADA, in Switzerland: Antidoping Switzerland) must be taken into account when treating effort asthma [21].

Inhaled corticosteroids and leukotriene antagonists are not on the doping list and can be used without restriction. Some beta-sympathomimetics, on the other hand, are banned altogether, while others are subject to limits. Oral steroids are prohibited in competition.

International athletes are also subject to additional rules for reporting diagnosis and medications, which vary by sport federation. In this case, it is recommended to consult a pulmonologist or sports physician.

A review of the substances used can be performed at www.antidoping.ch.

Forecast

The prognosis of effort asthma, as with other forms of asthma, is generally good. With adherence to the rules of conduct, largely complete control should be achievable with the wide range of medications. This means that there is no long-term restriction of lung function. In any case, EIB acquired under excessive training is completely reversible after the active sports period [22].

Literature:

- Wasserman K, et al: Respiratory physiology of exercise: metabolism, gas exchange, and ventilatory control. International Review of Physiology 1981; 23: 149-211.

- Dempsey J, et al: Limitations to exercise capacity and endurance: pulmonary system. Canadian Journal of Applied Sport Sciences/Journal Canadien Des Sciences Appliquées Au Sport 1982; 7(1): 4-13.

- Global Initiative for Asthma – Global Initiative for Asthma – GINA. (n.d.).

- Kotsimbos ATC, et al: IL-5 and IL-5 Receptor in Asthma. Memorias Do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 1997; 92(Suppl. 2): 75-91.

- Anderson SD, et al: Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: pathogenesis. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports 2005; 5(2): 116-122.

- Maurer MS: Challenge of exercise-induced asthma and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine 2009; 3(1): 13-19.

- Tan RA, et al: Exercise-induced asthma. Sports Medicine (Auckland, NZ) 1998; 25(1): 1-6.

- Fanta CH: Asthma. The New England Journal of Medicine 2009; 350(10): 1002-1014.

- Lund T, et al: Prevalence of asthma-like symptoms, asthma and its treatment in elite athletes. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 2009; 19(2): 174-178.

- Weiler JM, et al: Pathogenesis, prevalence, diagnosis, and management of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: A practice parameter. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology 2010; 105(6 Suppl.): S1-47.

- Helenius IJ, et al: Asthma and increased bronchial responsiveness in elite athletes: Atopy and sport event as risk factors. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 1998; 101(5): 646-652.

- Bougault V, et al: Bronchial challenges and respiratory symptoms in elite swimmers and winter sport athletes: Airway hyper-responsiveness in asthma: Its measurement and clinical significance. Chest 2010; 138(2 Suppl): 31S-37S.

- Parsons JP, et al: An official American thoracic society clinical practice guideline: Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2013; 187(9): 1016-1027.

- Rundell KW, et al: Exercise and other indirect challenges to demonstrate asthma or exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in athletes. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2008; 122(2): 238-246.

- Anderson SD, et al. (2013): Assessment of EIB. What You Need to Know to Optimize Test Results. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America 2013; 33(3): 363-380.

- King CS, et al: Clinical asthma syndromes and important asthma mimics. Respiratory Care 2008; 53(5): 568-580, discussion 580-582.

- Cardoos N: Overtraining syndrome. Current Sports Medicine Reports 2015; 14(3): 157-158.

- Stickland MK: Effect of warm-up exercise on exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 2012; 44(3): 383-391.

- Duong M: The effect of montelukast, budesonide alone, and in combination on exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2012; 130(): 535-539.

- Mickleborough TD, et al: Protective effect of fish oil supplementation on exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in asthma. Chest 2006; 129(1): 39-49.

- Wada: World Anti-Doping Code. World Anti-Doping Agency, Montreal, 2015: 1-116.

- Bougault V, et al: Airway hyper-responsiveness in elite swimmers: Is it a transient phenomenon? Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2011; 127(4): 892-898.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(11): 32-36