The history of falls in geriatric patients is usually fuzzy and not very purposeful. In the search for possible causes of falls, the structured assessment of the gait pattern is far more important than technical clarifications. Muscular deficits of the calves and hips are common causes of gait disorders in geriatric patients. Balance training for fall prevention is particularly effective when additional cognitive tasks are set. Other important aspects of fall prevention include good footwear, removal of trip hazards, visual acuity improvement, and a high-protein diet. The target value for the vitamin D blood level is 75 nmol/l.

Are fall prevention measures useful for all older people?

Yes, definitely. It has been known for years that regular balance training such as Tai Chi [1] and vitamin D supplementation have a positive effect on the incidence of falls in healthy seniors [2]. However, the focus of the clinician or primary care physician is usually on patients who are already at increased risk for a fall or have already experienced falls due to a gait disorder.

With these patients, how helpful is it to know why they fell last?

In principle, this is very important. However, clinical experience shows that we have to rely mainly on the patient’s own medical history – and unfortunately this is rarely helpful for a clear etiological assignment of the fall. The fall event and its interpretation usually sound somewhat different when the patient repeatedly describes it. This phenomenon is additionally accentuated in the case of cognitive impairment. In addition, a high suggestive effect is to be expected especially with questions about possible brief unconsciousness.

Does this clarify too much in the direction of syncope?

Absolutely. Syncope as a cause of falls accounts for only a small percentage of the elderly population. According to a compilation of various studies, it should even be only 0.3%! Of this small proportion, moreover, it is the orthostatic and neurogenic variants that are prominent, while cardiogenic syncope accounts for an even smaller proportion [3]. Conclusion: Even today, too much money is spent on technical examinations with unhelpful outcomes [4]. Systematic recording and subsequent modification of fall risk factors are much better than excessive technical clarifications and a blurred look back (self-history). Central to this is the structured assessment of a gait and balance disorder, which usually results from the superimposition of diverse pathologies.

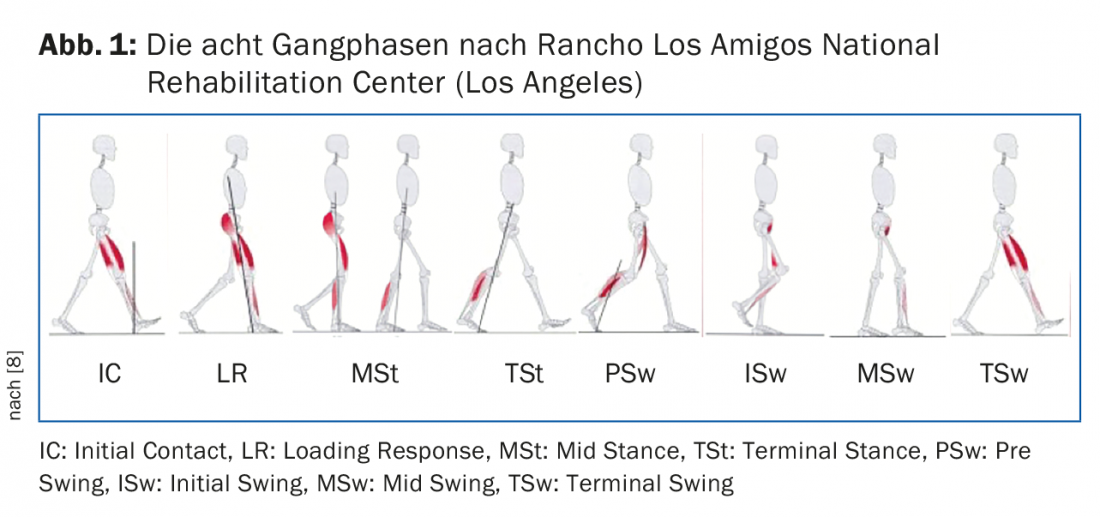

What is meant by a structured assessment of gait and balance disorder?

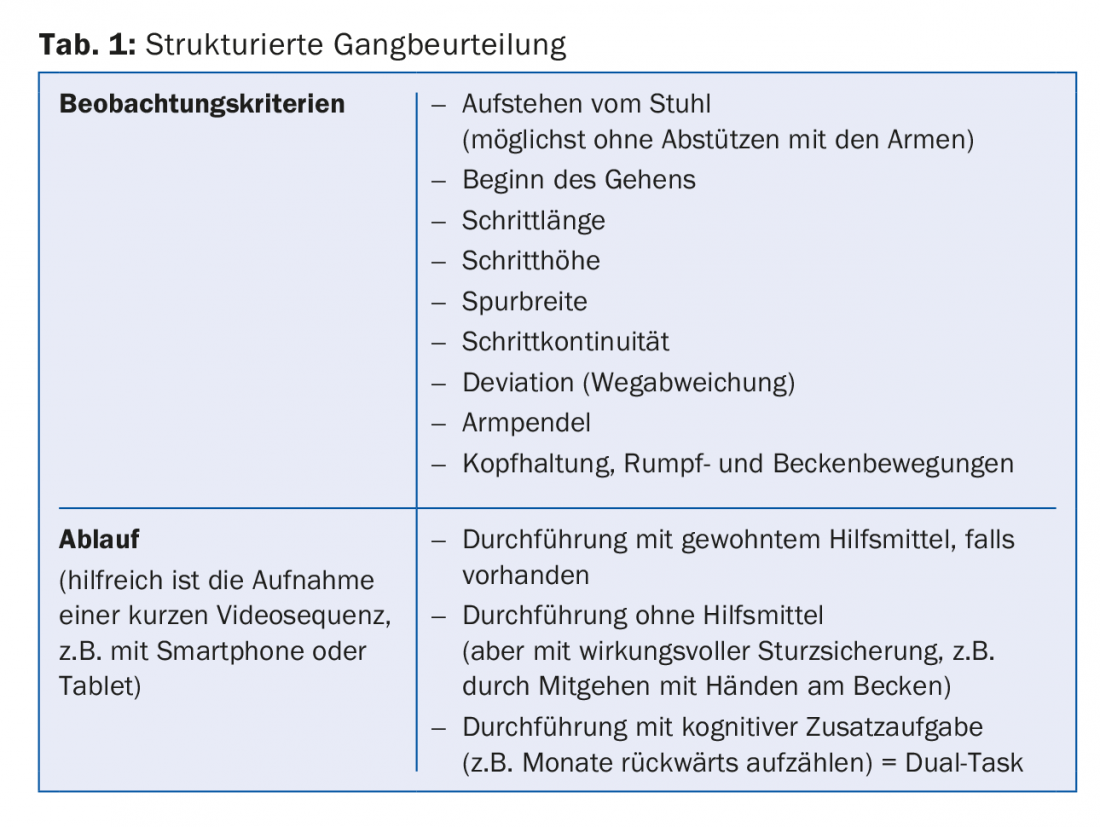

It doesn’t have to be a time-consuming thing. It is enough to look at how the patient gets up and walks a few meters. It is important to have the relevant observation criteria in mind (Tab. 1) and to know what normal walking should look like (Fig. 1) [5]. If one has an idea of this, one can recognize deviations quite quickly and can carry out further targeted tests to penetrate to the causes of the walking disorder.

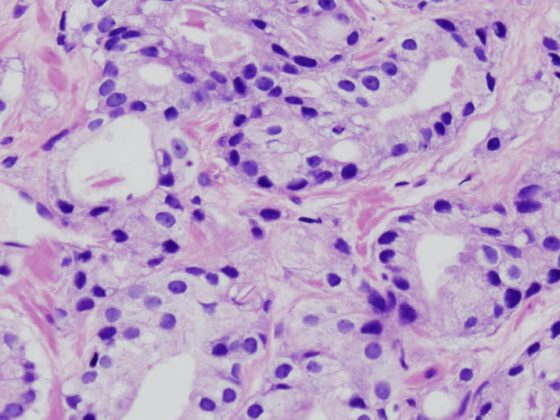

What are common causes of geriatric gait disorder?

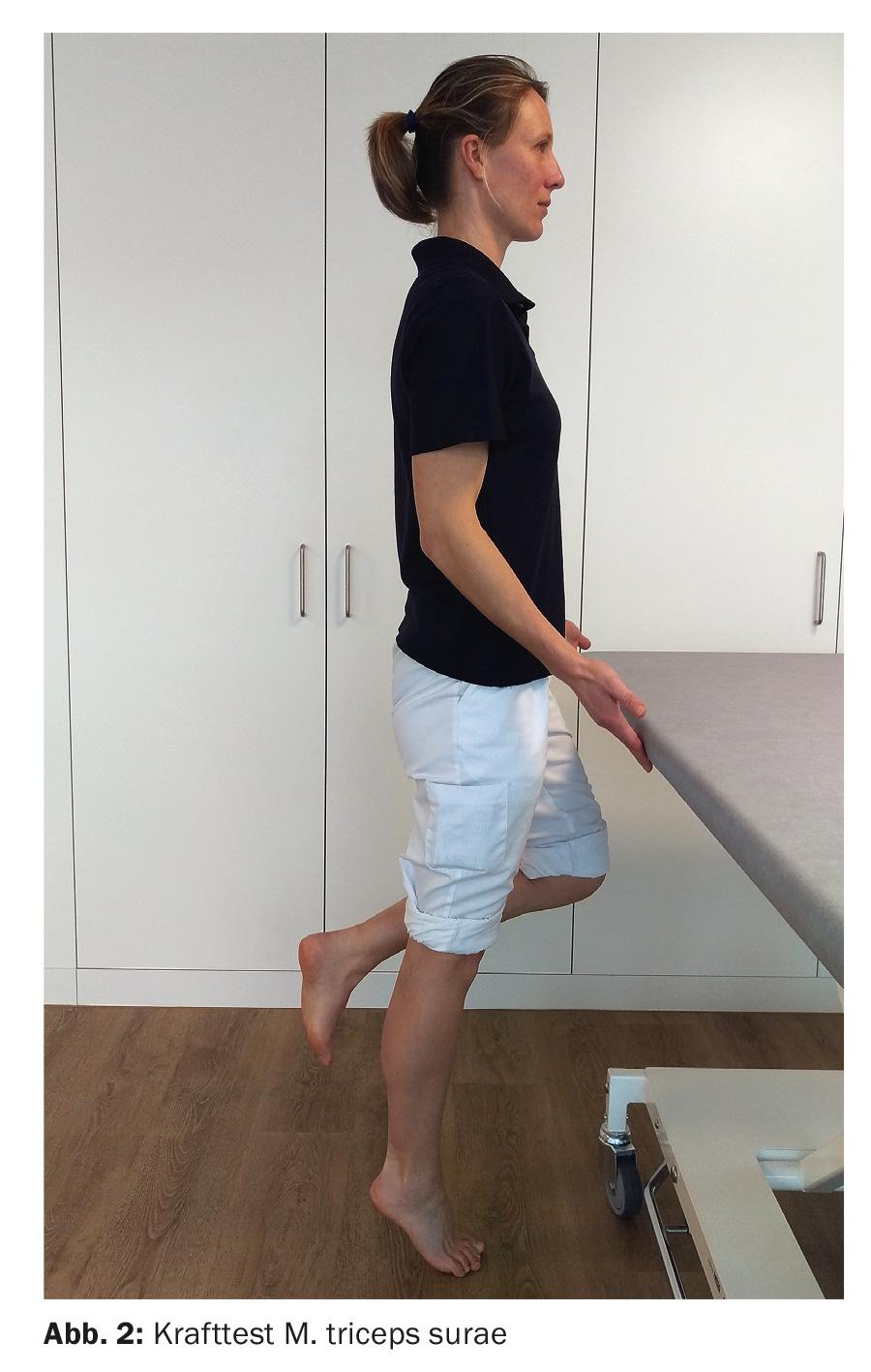

Often these are muscular deficits. In old age, the strength of the calf muscles often decreases at an above-average rate, although it is precisely these muscles that are of enormous importance for step generation. In the gait pattern, this can be seen in excessive knee joint flexion in the single-leg phases, but also in an insufficient stride length and a slow walking pace. If you suspect the calf muscles, you can test their strength quickly and easily by standing on one leg with the toes – the knee must remain extended (Fig. 2). For a normal gait pattern in old age, this exercise must be performed at least five times in our experience (normal value for middle age at least twenty times) [5,8].

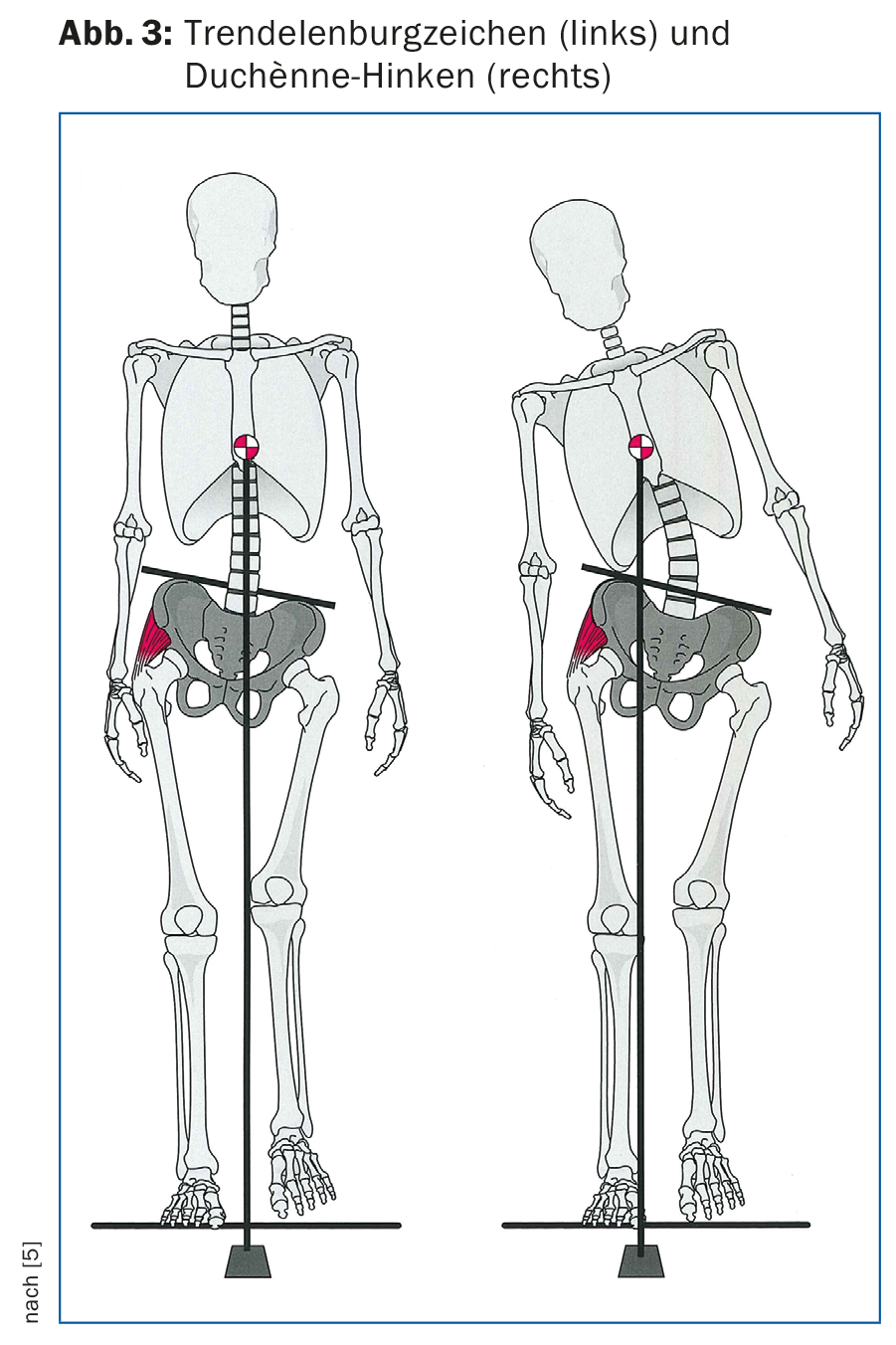

Likewise, the hip joint abductors are often too weak, not infrequently after implantation of a total hip prosthesis. This is reflected in a very typical gait pattern, the so-called “Trendelenburg sign,” a contralateral lowering of the pelvis (Fig. 3, left). A compensatory lateral tilt of the upper body toward the weak side, the so-called “Duchènne limp,” can often be observed (Fig. 3, right).

What are appropriate training programs for fall prevention?

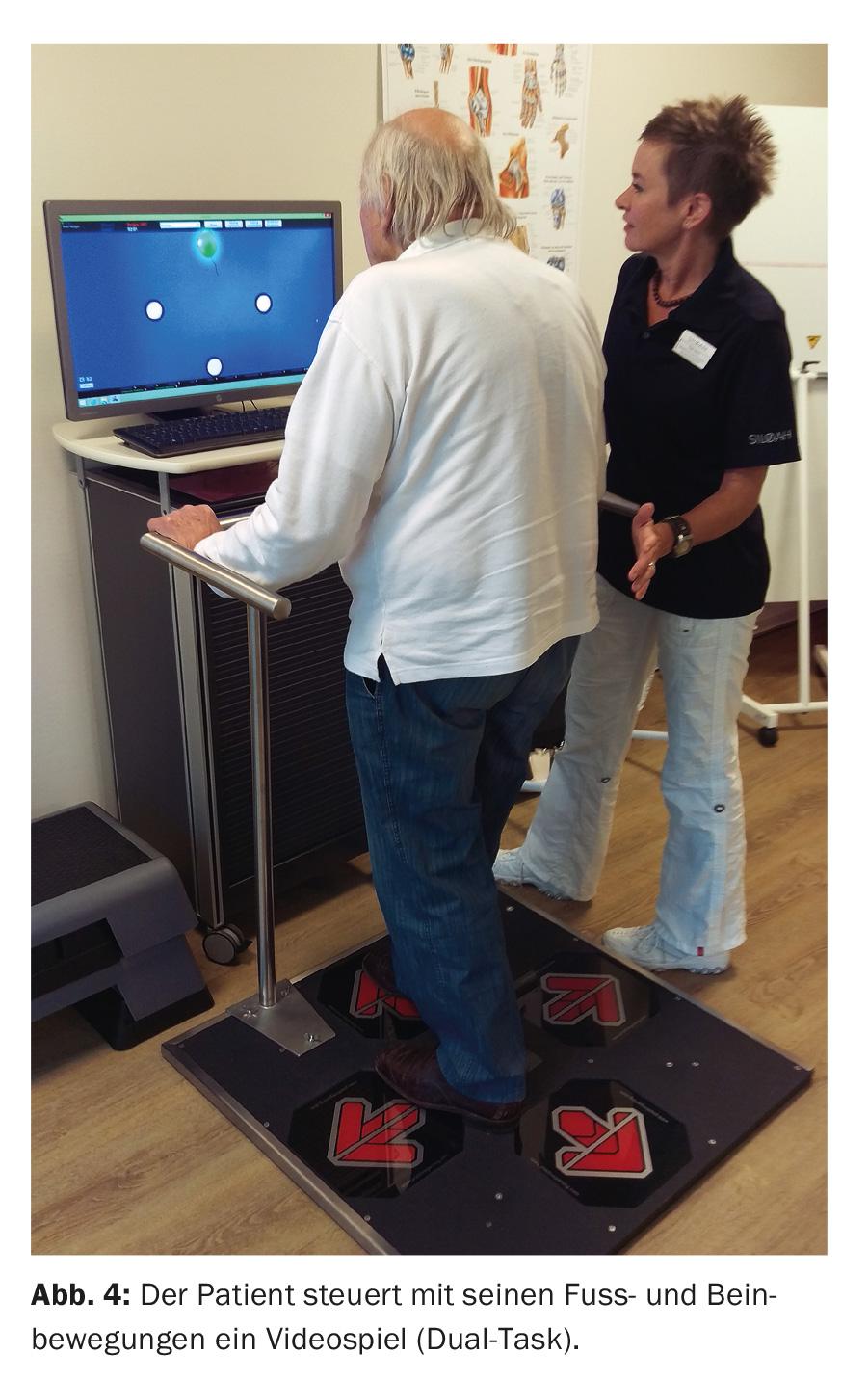

If strength deficiencies have been identified, they will certainly need to be addressed through targeted training. Balance training is the most important aspect of fall prevention. Activities that demand a high level of concentration and body control have proven to be particularly effective. Here, in addition to Tai Chi and Jacque Dalcroze Rhythmic, specific cognitive-motor training is also of interest, e.g. on a Step Plate (Fig. 4).

How important is it to eliminate fall traps at home?

Very important, since most falls occur in the home environment. A good falls prevention program always includes a housing assessment [6]. Often, a targeted questioning is sufficient here. Classic fall traps include slippery carpets or inadequate lighting. Both can be corrected relatively easily. However, the importance of footwear should not be underestimated in this context.

What are “good” and “bad” shoes?

A shoe should first of all fit well, i.e. not be too big or too small, and include the heel area. A typical open slipper is unsuitable for the geriatric foot. If sensitivity problems are already present, a firmer sole is preferable to too much suspension so that the ground can be felt better. A small heel often helps with forward propulsion and is better than shoes that are too flat, for example, if you have calf weakness. For outdoors, an ankle-high shoe with a good tread gives the best grip.

What role does vitamin D play?

In our patients at increased risk for falls, we aim for daily vitamin D supplementation of (800-)1000 IU per day. However, weekly administration of 7000 IU is also possible, provided that it makes administration simpler and safer. Only if a high-risk constellation is suspected (e.g. fracture, dementia) do we sometimes determine the blood level in order to be able to forcefully up-dose in the case of severe deficiency (e.g. once a week 45,000 IU for four to six weeks). The target blood level is 75 nmol/l (30 ng/ml) [7].

What other starting points are there for risk modification?

These important starting points are systematically recorded in the geriatric assessment. General muscle wasting (sarcopenia) is particularly common. This must be counteracted not only with training, but also with an improved, protein-rich diet. Sensory problems are also highly relevant, with visual acuity improvement being a particularly realistic goal. The critical evaluation of the usually long list of medications with regard to substances that promote falls is also always part of the process.

Incidentally, the influence of diffuse degenerative and microvascular brain changes on central motor control is underestimated, without the need for a typical neurological clinical picture. Thus, already in early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, discrete gait changes (especially when performed with additional cognitive task!) and increased falls are found. The example underlines that a sound gait assessment always includes a cognitive assessment in order to be able to provide optimal advice and therapy in the case of incipient dementia.

Literature:

- Wolf SL, et al: Reducing frailty and falls in older persons: an investigation of Tai Chi and computerized balance training. Atlanta FICSIT Group. Frailty and Injuries: Cooperative Studies of Intervention Techniques. J Am Geriatr Soc 1996; 44(5): 489-497.

- Moyer VA, et al: Prevention of falls in community-dwelling older adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157(3): 197-204.

- Rubenstein LZ, et al: The epidemiology of falls and syncope. Clin Geriatr Med 2002; 18: 141-158.

- Mendu ML, et al: Yield of diagnostic tests in evaluating syncopal episodes in elderly patients. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169(14): 1299-1305.

- Götz-Neumann K: Understanding walking. Gait analysis in physiotherapy. Georg Thieme Verlag, 2006.

- www.bfu.ch/de/fuer-fachpersonen/sturzprävention.

- Lamy O, et al: Osteomalacia and vitamin D. Swiss Medical Forum 2015; 15(48): 1118-1121.

- Lunsford BR, Perry J: The Standing Heel-Rise Test for Ankle Plantar Flexion: Criterion for Normal. Physical Therapy 1995; 8: 694-698.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(3): 26-31