At the Update Refresher Internal Medicine, the two cardiologists from the Stadtspital Triemli Prof. Dr. med. Franz Eberli and PD Dr. med. David Kurz discussed news and views from current research. Apparently, fat is not as unhealthy as it has been propagated for a long time. And what benefit does aspirin actually provide in primary prevention? Lastly, an update was given on the diagnosis, acute treatment, and follow-up of acute coronary syndrome.

Currently, a rethink is taking place in cardiology in several areas. For example, regarding the long-held principle of “fat kills” – that is, the assumption that replacing fats with carbohydrates and saturated fatty acids with omega-3 unsaturated fatty acids can reduce cardiovascular risk. The announcement of the 2015 U.S. Dietary Recommendations puts this principle badly out of whack. “The guidelines will truly contain dynamite for traditional cardiology,” said Prof. Franz Eberli, MD, Triemli City Hospital, Zurich.

Fat and cholesterol – no problem?

The scientific report of the Guideline Committee says in black and white: “Reducing total fat (replacing total fat with overall carbohydrates) does not lower cardiovascular disease risk”. So there is little room for interpretation. Avoiding fat by following a low-fat diet is clearly not recommended. Replacing fat with carbohydrate could lead to hypertriglyceridemia and a decrease in HDL cholesterol and was therefore counterproductive.

The Advisory Board also makes statements on the subject of cholesterol that initially make one swallow empty: Cholesterol-containing foods may be eaten without hesitation, since the ingested cholesterol has no influence on the cholesterol level. In principle, therefore, there is no preference for certain food substances. “You can eat anything, but you should eat a balanced diet,” Prof. Eberli summarized. However, it is still desirable to replace saturated fatty acids with unsaturated ones.

What are these recommendations based on? First, on a meta-analysis by Harcombe et al. [1], which failed to demonstrate any benefit of the low-fat diet for either all-cause or CHD mortality. An even more radical conclusion was drawn in the PREDIMED study of 2013 [2]: Compared to the Mediterranean diet with olive oil (1 l per week!) and nuts, the low-fat diet performed significantly worse in the composite cardiovascular endpoint (myocardial infarction, stroke, death). The reason for this was mainly the significant differences in stroke incidence, as the individual analysis showed. Last but not least, a high-fat diet seems to have a favorable effect on blood pressure and lipid profile compared to a carbohydrate diet [3].

Aspirin in primary prophylaxis

In other areas, too, the previous paradigm is being challenged by recent studies. As early as 2009, a meta-analysis made it clear that while the use of aspirin is effective and important in secondary prevention, it is questionable in primary prevention [4]. Here, the reduction of occlusive events must be carefully weighed against the increased risk of bleeding. In diabetics, aspirin also does not appear to produce a significant reduction in cardiovascular events in primary prevention [5] – nor in patients with other atherosclerotic risk factors such as hypertension or dyslipidemia [6]. Overall, therefore, the data are sobering and do not justify primary prophylactic use of aspirin.

Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) – State of the Art

“Highly sensitive troponin assays have now become established in the diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome,” said PD David Kurz, MD, Triemli City Hospital, Zurich. This is also shown by the new definitions of myocardial infarction, where the weighting has shifted towards cardiac biomarkers, which now clearly dominate over the other diagnostic pillars “ECG” and “clinical picture”. “In principle, the new assays look at the same things as before, but with significantly increased sensitivity. This allows for earlier diagnosis and earlier exclusion of myocardial infarction. We can now make a quantitative statement rather than just a qualitative one.” To this end, a diagnostic algorithm with different cut-off levels and the “rise and/or fall of troponin” principle has been introduced and is becoming increasingly important in decision-making.

Oxygen for every infarct?

“Almost reflexively, oxygen is administered in ACS today – but do all patients really benefit from O2 administration?” asked Dr. Kurz. Beneficial effects are at least controversial, and there is little evidence that O2 is beneficial outside of symptomatic therapy. Hyperoxia increases vascular resistance and possibly induces increased reperfusion injury by O2 free radicals. In 2015, the randomized AVOID trial tested whether STEMI patients benefit from oxygen administration before hospitalization [7]. At the hospital, all confirmed STEMI patients underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with or without oxygen. It was found that oxygen administration is useful only in dyspneic or hypoxic (saturation <94%) subjects. In all others, however, there was no evidence of beneficial effects, but rather of harmful effects (among other things, infarcts were significantly greater).

Preloading with second antiplatelet agent controversial

Should ACS patients be pretreated with a second antiplatelet agent (clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticagrelor) in addition to aspirin at first contact with the medical system before coronary angiography-as recommended in previous guidelines? “In NSTEMI patients, the ACCOAST trial [8] clearly states that pretreatment (with prasugrel) should be delayed until coronary angiography has been performed and a decision has been made about the correct therapy-PCI, aortocoronary bypass surgery, or drug therapy,” Dr. Kurz noted. In 5-15% of cases, angiography shows that bypass surgery is the best revascularization method. Preloading here delays implementation by five days. The previous recommendations were based on uncertain data with clopidogrel.

In STEMI patients, “preloading” is still of uncertain significance, but at least not dangerous according to the ATLANTIC trial [9].

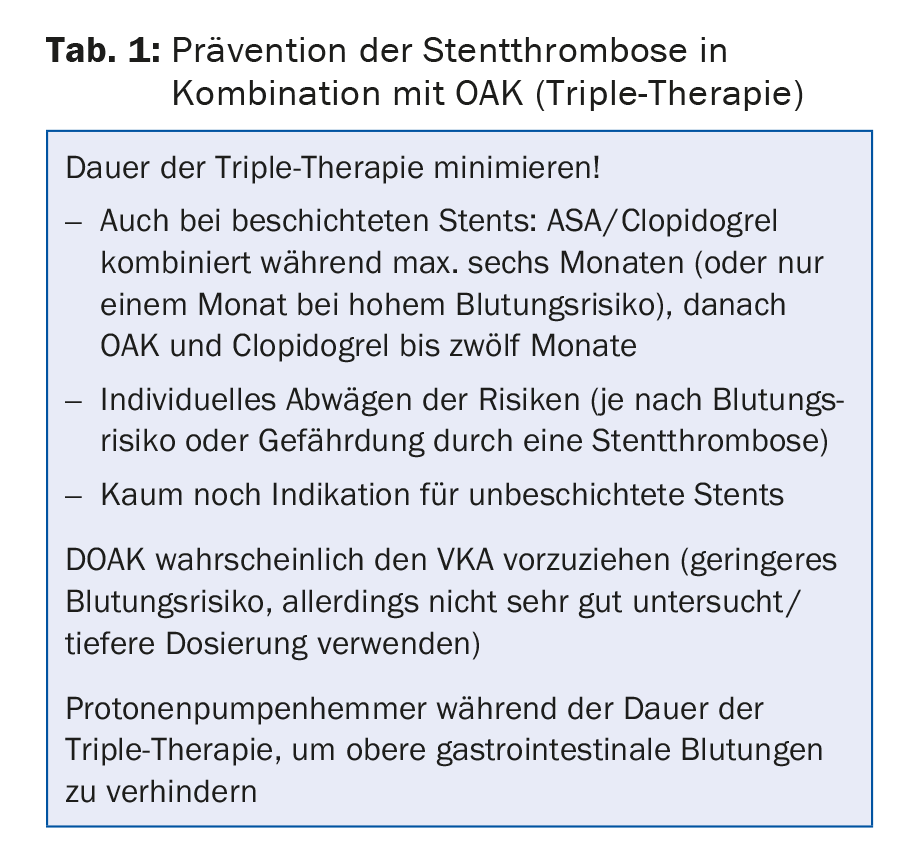

Triple Therapy

The rationale for triple therapy, that is, dual antiplatelet therapy in patients on oral anticoagulation, is the simultaneous prevention of stent thrombosis (aggregation inhibitors better) and stroke in atrial fibrillation (anticoagulants better). “The problem is, patients bleed more: after 30 days, the bleeding rate is 2.2%, and after 12 months, it’s 12%,” Dr. Kurz said.

The newer potent antiplatelet agents prasugrel and ticagrelor are contraindicated in triple therapy because of the increased risk of bleeding [10]. Therefore, only clopidogrel can be considered. Other points of discussion regarding platelet inhibition with OAKs involve the number of agents and the duration of triple therapy.

Number of active ingredients: Are two possibly better tolerated than three? In AF after PCI, dual therapy with clopidogrel and oral anticoagulation significantly reduced the risk of bleeding by 64% compared with triple treatment with OAK, aspirin, and clopidogrel (cumulative incidence 19.4 vs. 44.4%), according to the WOEST study [11]. However, closer inspection then revealed that the difference was driven primarily by minor bleeding, and major bleeding was not significantly less frequent. WOEST was then also strongly criticized. “People didn’t really want to believe it,” Dr. Kurz said, summarizing the concerns at the time.

Duration of triple therapy: the ISAR-Triple study [12] showed that six weeks of triple therapy after PCI performed no better (but also no worse) than six months of therapy. The shorter duration did not reduce the bleeding rate or increase the incidence of ischemic events.

Table 1 summarizes the recommendations for triple therapy.

Source: Update Refresher Internal Medicine, December 1-5, 2015, Zurich.

Literature:

- Harcombe Z, et al: Evidence from randomised controlled trials did not support the introduction of dietary fat guidelines in 1977 and 1983: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Open Heart 2015; 2(1): e000196.

- Estruch R, et al: Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med 2013; 368(14): 1279-1290.

- Appel LJ, et al: Effects of protein, monounsaturated fat, and carbohydrate intake on blood pressure and serum lipids: results of the OmniHeart randomized trial. JAMA 2005; 294(19): 2455-2464.

- Antithrombotic Trialists′ (ATT) Collaboration: Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet 2009; 373(9678): 1849-1860.

- De Berardis G, et al: Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in people with diabetes: metaanalysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2009; 339: b4531.

- Ikeda Y, et al: Low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in Japanese patients 60 years or older with atherosclerotic risk factors: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014; 312(23): 2510-2520.

- Stub D, et al: Air Versus Oxygen in ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2015; 131(24): 2143-2150.

- Montalescot G, et al: Pretreatment with prasugrel in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(11): 999-1010.

- Montalescot G, et al: Prehospital ticagrelor in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(11): 1016-1027.

- Sarafoff N, et al: Triple therapy with aspirin, prasugrel, and vitamin K antagonists in patients with drug-eluting stent implantation and an indication for oral anticoagulation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61(20): 2060-2066.

- Dewilde WJ, et al: Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2013; 381(9872): 1107-1115.

- Fiedler KA, et al: Duration of Triple Therapy in Patients Requiring Oral Anticoagulation After Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation: The ISAR-TRIPLE Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65(16): 1619-1629.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(2): 32-35