Mucolytics are included in several guidelines as a treatment option for patients with frequent exacerbations. According to GOLD, they can reduce exacerbations and marginally improve health status. However, evidence is currently lacking. Researchers have looked into this in a review paper and have tried to determine the actual effect of this class of drugs.

Internationally, there is no consensus on the place of mucolytics in the treatment of COPD. The American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society (ATS / ERS) guidelines for preventing exacerbations state, “For patients with COPD with moderate or severe airflow obstruction and exacerbations despite optimal inhaled therapy, we recommend treatment with an oral mucolytic to prevent future exacerbations.” However, this is considered only a conditional recommendation based on low quality evidence. Researchers led by Dr. Phillippa Poole of the Department of Medicine at the University of Auckland, New Zealand, evaluated 38 randomized, placebo-controlled trials involving a total of 10,377 adult patients who had either COPD or chronic bronchitis in a Cochrane review (15 trials examined the use of mucolytics only in those with COPD, the others those with chronic bronchitis, COPD, or both) [1]. This was based on an earlier 2015 review also conducted by Poole.

All but four studies were described as double-blind. The average age of the participants ranged from 40 to 71 years. The percentage of current or former smokers ranged from 55% to 100%. The studies considered had a duration of between two months and three years and used various expectorants, including N-acetylcysteine (NAC), carbocysteine and Erdostein. The expectorants were taken orally up to three times per day. The use of inhaled mucolytics was not considered. Study objectives included endpoints such as disease relapses, hospitalizations, quality of life, lung function, and adverse events. Studies in patients with asthma or cystic fibrosis were excluded, as were those on inhaled mucolytics and combinations of mucolytics with antibiotics and with bronchodilators, and studies on deoxyribonuclease or proteases.

Reduction of effects in recent studies

Mucolytics increase sputum expectoration by altering the physical properties of secretions, for example, by degrading the mucin polymers, fibrin, or DNA in respiratory secretions, making them less viscous. Reducing viscosity makes it easier for the body to cough and reduces the risk of bacterial contamination. Classical mucolytics such as N-acetylcysteine exert their effects by depolymerizing mucin glycoproteins via a hydrolysis reaction. One study found that NAC can improve lung function, but there was uncertainty about whether this was actually due to its antioxidant ability or happened because of other influencing factors. Given that oxidative stress is a reinforcing mechanism in COPD, this property of N-acetylcysteine may be useful in chronic respiratory disease. Mucolytics are administered in combination with, and not in place of, other COPD therapies such as inhaled long-acting beta agonists (LABA) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA).

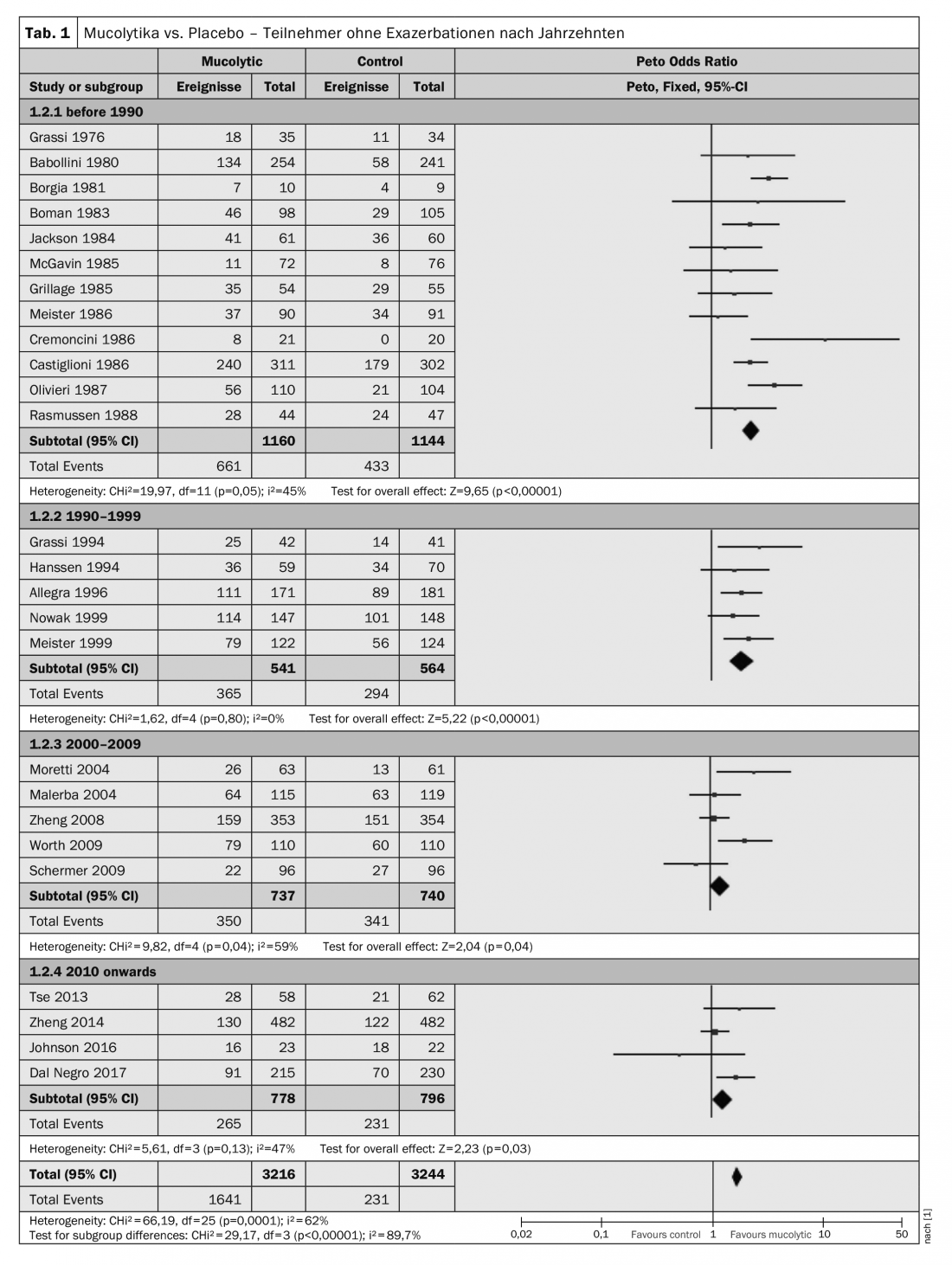

The tendency for participants given mucolytics to be more likely to be exacerbation-free was observed in almost all studies. However, heterogeneity was high (I²=62%), which is why Poole et al. have performed a post-hoc subgroup analysis showing results of double-blind studies organized by year of publication and subdivided by decade of publication. Here, remarkably, there was a tendency for more recent studies to yield more conservative results: studies published before 1990 (Peto OR 2.34; 95% CI 1.97-2.79) and between 1990 and 1999 (Peto OR 1.91; 95% CI 1.50-2.44) had larger effect sizes than those published between 2000 and 2009 (Peto OR 1.24; 95% CI 1.01-1.54) or since 2010 (Peto OR 1.28; 95% CI 1.03-1.59). (Table 1) . It should also be noted that of the six studies with adequate allocation concealment, only one reported a noticeable benefit of treatment in preventing exacerbations.

Two factors, according to Poole et al. The main factors contributing to this result were improved study designs, implementation and reporting over the years. Also, more stringent definitions of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have been used in recent studies. But another is improved COPD care: management of COPD now includes support for smoking cessation, vaccination, pulmonary rehabilitation, and use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), LABAs, and anticholinergics, which can affect exacerbation frequency or severity.

No clinical difference in quality of life

Although global assessments of well-being were frequently reported by participants and/or clinicians, only 10 studies used validated health-related quality of life (HRQoL) instruments in participants with COPD. The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) was used in nine of them. The SGRQ total score is derived from scores in three subscales – symptoms, activities, and effects – to obtain a score of 100. Lower values indicate a better quality of life.

Although the pooled result favored mucolytics over placebo, the confidence interval did not include a difference (MD -1.37; 95% CI -2.85-0.11; n=2721). Considerable heterogeneity between studies was evident (I²=64%). This effect does not meet the clinically important minimum difference of 4 units in SGRQ however, one cannot evaluate the effects of mucolytics at the population level without performing a responder analysis, the authors explain. This was not possible until now.

Strengthening previous results

For the researchers, the results of their review reinforce previous research indicating that participants given a mucolytic for an average of nine months are more likely to be exacerbation-free during that time. Mucolytics may be associated with a reduction in impairment of about half a day per participant per month.

With the addition of more recent studies, there is increasing certainty that mucolytics do not have a significant effect on lung function decline or mortality. However, Poole and her colleagues point out that some of the results can only be interpreted with particular caution because of heterogeneity.

The analyses in their review suggest that mucolytics may additionally have an impact on the duration and severity of exacerbations that occur, as well as the likelihood of antibiotic use. Data from four studies suggest that mucolytics are associated with reduced hospitalization rates. It would be helpful, the authors said, if future studies examined this outcome, as this is where most of the costs of more severe disease occur. Few other pharmacological treatments reduce hospitalization to the same extent.

Literature:

- Poole P, Sathananthan K, Fortescue R: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019; 5; doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001287.pub6

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2020; 2(2): 21-23.