Focal treatment of prostate cancer is a new strategy that complements the two treatment options of “active surveillance” and radical prostatectomy. The goal is to target the clinically significant tumor while monitoring the residual prostate tissue. This allows for significantly better preservation of erectile function and continence. Due to the initial detailed work-up and subsequent monitoring with multimodal magnetic resonance imaging and extended biopsy, the risk of relevant tumor progression of untreated areas is reduced to a minimum. The possibility of focal therapy for prostate cancer should be explained in detail to the patient during the educational interview before deciding on a radical treatment strategy.

Prostate cancer is the most common malignancy in men and the second leading cause of cancer death in industrialized countries [1] and therefore needs to be seriously considered in terms of socioeconomic and health aspects.

When a patient is newly diagnosed with prostate cancer, he and his treating physician are often faced with a difficult decision; after all, the currently available established therapeutic options are at opposite ends of the therapeutic spectrum.

On the one hand, there is “active surveillance”, in which a wait-and-see attitude with close monitoring is adopted despite a known tumor diagnosis. However, this therapeutic strategy for low-malignant prostate cancer is only slowly gaining acceptance in Europe and the USA [2,3]. On the other side of the spectrum are the so-called radical treatments of the entire prostate, performed either in the form of a radical prostatectomy or as radiotherapy. Unfortunately, current studies are not able to clearly help the patient or treating physician in his decision. Currently, 1055 men need to be PSA screened and 37 diagnosed/treated with prostate cancer to prevent one prostate cancer death [4]. The risks for side effects of radical therapy are 30-90% for erectile dysfunction, 5-20% for incontinence, and 5-20% for colon complications [5,6].

The consistent advancement of surgical techniques using laparoscopy and robotics has led to improvements in blood loss, wound pain, and hospitalization time, but a significant reduction in side effects and improved tumor control have not been demonstrated [5,7]. It seems that the anatomical-biological limits of what is possible have been reached here.

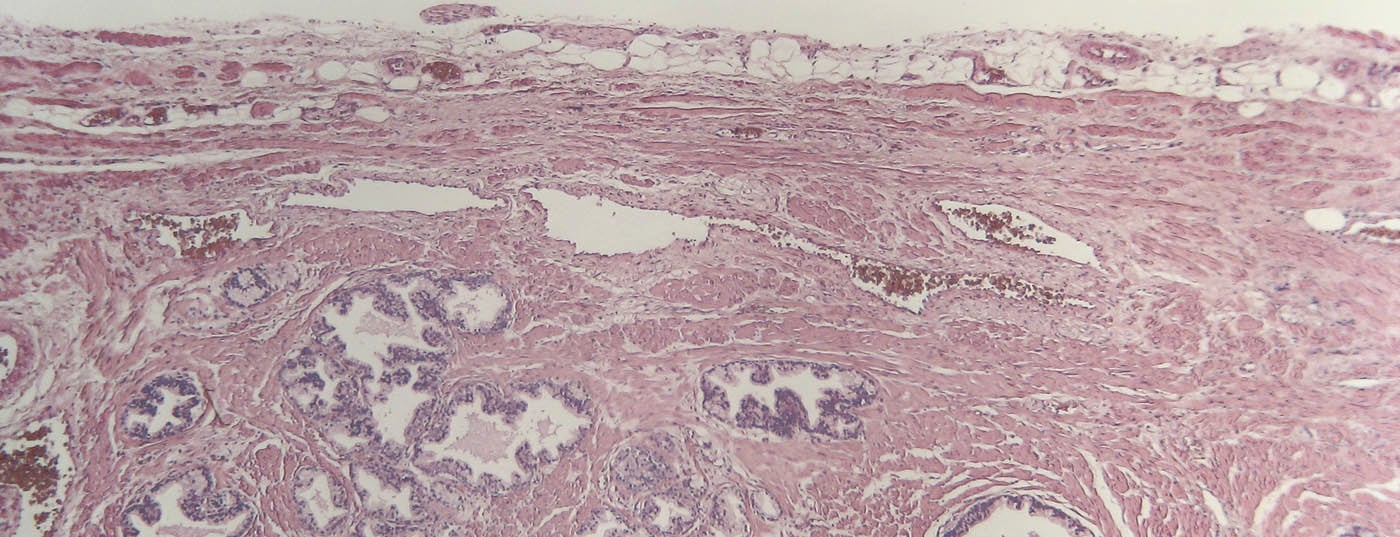

Localization and significance of prostate carcinoma.

Focused (focal) treatment of the areas suspected of tumor can minimize unwanted side effects. Focusing therapy on the actual tumor has already been successful in other organs such as kidney, liver and lung. In prostate cancer, this concept was not pursued for a long time, as multifocal involvement of the organ was assumed. However, histologic studies show that up to 50% of patients undergoing radical prostatectomy have only unifocal or unilateral involvement and thus would qualify for focal therapy [8]. These findings are not new – but even more so are the technical possibilities, which are mandatory prerequisites for establishing the therapy concept of “focal therapy”: the treatment of significant prostate cancer while simultaneously monitoring the remaining prostate. Detailed localization including characterization and classification of all tumors within the prostate, in terms of both diagnosis and monitoring, is ensured by multimodal magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) and enhanced prostate biopsy. Precise and targeted focal ablation is performed using high-intensity focused ultrasound waves (HIFU).

Multimodal magnetic resonance imaging

The mpMRI includes T1- and T2-weighted sequences as well as imaging of diffusion restriction and dynamic contrast-enhanced images with intravenous gadolinium. The same examination technique can also be used to assess the stage of tumor aggressiveness remarkably well [9]. Recent studies show that mpMRI has a high negative predictive value of 80-95% for clinically significant carcinoma sites larger than 0.5 cm3 [10,11].

Extended prostate biopsy

Combined with a so-called extended prostate biopsy (template biopsy), which is performed under short anesthesia and perineally, the aggressiveness and localization of the malignant change can be defined even more precisely. With this checkerboard tissue sampling, a sensitivity of more than 90% is achieved [12–14]. The complication rate and side effects of transperineal removal of an average of 40 tissue cylinders were investigated in a larger study [15]. This showed no significant complications (>Clavien grade II) and likewise no side effects on micturition or erectile function one month after biopsy.

Focal therapy option

Focal therapy of prostate carcinoma can basically be performed with different energy sources. Described are HIFU, cryosurgery, photodynamic therapy, brachytherapy, radiofrequency ablation, and the thermal laser [16,17]. Due to its non-invasive nature, proven successful tissue damage and thanks to real-time monitoring, HIFU is the best studied method, which is currently being analyzed in detail in further phase II studies. HIFU treatment is based on a series of high-energy ultrasound waves that are focused on a focal point during treatment. Due to the temperature rise, coagulative necrosis occurs in a piece of tissue measuring approximately 3×3×10 mm. Due to the sound bundling, no thermal damage occurs along the ultrasonic beam.

During focal therapy of prostate cancer, also under short anesthesia, the prostate is measured three-dimensionally by ultrasound and the regions with tumor tissue are selectively ablated. This therapy is remarkably well tolerated and patients can leave the hospital after two days with a Cystofix catheter. Studies of HIFU demonstrate impotence rates between five and 15%, with almost no incontinence [18–22].

Focal therapy could thus bridge the gap between “active surveillance” and radical therapy and provide patients with newly diagnosed prostate cancer the opportunity to treat their cancer without significant side effects. Insignificant tumor tissue deliberately left untreated must continue to be monitored in subsequent years, and a potentially new significant tumor focus must be treated repeatedly. Overall, this could reduce the number of radical therapies with their significant side effects, or at least delay radical therapy such that the patient can experience years without side effects. A theoretical residual risk remains, as a tumor mass may be missed during diagnosis or due to inadequate/insufficient localization during therapy. Thus, there is a risk of a potentially metastatic tumor, which could consequently develop a progression over time. However, this general risk is very small, as we can assume a general “lead time bias” of about five years for prostate cancer due to PSA screening [23]. Even in a Swedish study with a relatively large proportion of patients with high-risk prostate cancer, only a six percent absolute risk reduction for prostate cancer-specific death was shown after 15 years with radical therapy compared with “watchful waiting” [24]. Based on the detailed follow-up scheme (PSA, extended prostate biopsy, mpMRI) with possible follow-up treatments, we assume a potential risk of far below 6% for focal therapy

Selection of the right patients for focal therapy

Therapeutic procedures capable of preserving residual prostate tissue after ablation are considered “focal therapy” by current definition. Although total bilateral HIFU treatment is possible, it leads to a significant increase in side effects, comparable to radical therapy options. Currently, focal therapy should therefore only be used for patients with unilateral dominant, small tumors. These patients can be expected to have a very low rate of urogenital and rectal side effects.

However, for patients with large, multifocal, or poorly differentiated tumors (>Gleason 3+4), radical treatment strategies continue to be considered ideal options, granting oncologic safety that justifies the known side effects.

Finally, caution should be exercised in patients with proven, insignificant, low-risk prostate cancer. Despite the minor side effects of focal HIFU, it is nevertheless reasonable to assume that for this group any treatment would represent overtreatment. All the more, these men will benefit from the precision of the new monitoring strategy with mpMRI and extended prostate biopsies, and in case of progression, the option of low side-effect treatment would always be preserved.

PD Dr. med. Dr. rer. nat. Daniel Eberli

Literature:

- Crawford ED: Epidemiology of prostate cancer. Urology 2003 Dec 22; 62: 3-12.

- Cooperberg MR, et al: Contemporary trends in low risk prostate cancer: risk assessment and treatment. The Journal of Urology 2007 Sep; 178: S14-19.

- Cooperberg MR, et al: The changing face of low-risk prostate cancer: trends in clinical presentation and primary management. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2004 Jun 1; 22: 2141-2149.

- Schroder FH, et al: Prostate-cancer mortality at 11 years of follow-up. The New England journal of medicine 2012 Mar 15; 366: 981-990.

- Hu JC, et al: Comparative effectiveness of minimally invasive vs open radical prostatectomy. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2009 Oct 14; 302: 1557-1564.

- Sanda MG, et al: Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. The New England journal of medicine 2008 Mar 20; 358: 1250-1261.

- Berryhill R, et al: Robotic prostatectomy: a review of outcomes compared with laparoscopic and open approaches. Urology 2008 Jul; 72: 15-23.

- Ahmed HU, et al: Will focal therapy become a standard of care for men with localized prostate cancer? Nature clinical practice Oncology 2007 Nov; 4: 632-642.

- Kobus T, et al: Prostate cancer aggressiveness: in vivo assessment of MR spectroscopy and diffusion-weighted imaging at 3 T. Radiology 2012 Nov; 265: 457-467.

- Vargas HA, et al: Performance characteristics of MR imaging in the evaluation of clinically low-risk prostate cancer: a prospective study. Radiology 2012 Nov; 265: 478-487.

- Vargas HA, et al: Diffusion-weighted endorectal MR imaging at 3 T for prostate cancer: tumor detection and assessment of aggressiveness. Radiology 2011 Jun; 259: 775-784.

- HU Ahmed DS, et al: Prostate cancer risk stratification and cancer mapping template transperineal prostate mapping biopsies. Abstract 436, AUA Annual Meeting 2008.

- Onik G, Barzell W: Transperineal 3D mapping biopsy of the prostate: an essential tool in selecting patients for focal prostate cancer therapy. Urologic oncology 2008 Sep-Oct; 26: 506-510.

- Al Baha Barqawi JL, et al: The role of three dimensional systematic mapping biopsy of the prostate in men presenting with apparent low risk disease based on extended transrectal biopsy. Abstract 439, AUA Annual Meeting 2008.

- Losa A, et al: Complications and quality of life after template-assisted transperineal prostate biopsy in patients eligible for focal therapy. Urology 2013 Jun; 81: 1291-1296.

- Ahmed HU, et al: Minimally-invasive technologies in uro-oncology: the role of cryotherapy, HIFU and photodynamic therapy in whole gland and focal therapy of localised prostate cancer. Surgical oncology 2009 Sep; 18: 219-232.

- Barqawi A, Crawford ED: Focal therapy in prostate cancer: future trends. BJU International 2005 Feb; 95: 273-274.

- Polascik TJ, et al: Nerve-sparing focal cryoablation of prostate cancer. Current opinion in urology 2009 Mar; 19: 182-187.

- Bahn DK, et al: Focal prostate cryoablation: initial results show cancer control and potency preservation. Journal of endourology / Endourological Society 2006 Sep; 20: 688-692.

- Lambert EH, et al: Focal cryosurgery: encouraging health outcomes for unifocal prostate cancer. Urology 2007 Jun; 69: 1117-1120.

- Ellis DS, et al: Focal cryosurgery followed by penile rehabilitation as primary treatment for localized prostate cancer: initial results. Urology 2007 Dec; 70: 9-15.

- Muto S, et al: Focal therapy with high-intensity-focused ultrasound in the treatment of localized prostate cancer. Japanese journal of clinical oncology 2008 Mar; 38: 192-199.

- Andriole GL, et al: Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. The New England journal of medicine 2009 Mar 26; 360: 1310-1319.

- Bill-Axelson A, et al: Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2011 May 5; 364: 1708-1717.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2014; 2(4): 16-18.