With age, diseases increase – and so does the likelihood of polypharmacy. However, this presents many challenges, as the heterogeneity and vulnerability of older people requires a differentiated approach. Patients with psychiatric disorders are particularly at risk for adverse drug reactions.

One in five people in Germany is older than 65, and six out of 100 have already passed the age of 80. With age, diseases increase, so the need for pharmacotherapy grows. Pharmacotherapy of the elderly is particularly challenging because the heterogeneity and vulnerability of the elderly requires a differentiated approach [1]. Elderly people with psychiatric disorders are at higher risk for adverse drug reactions, which is caused by both age and multimorbidity. Multimorbidity is already assumed when a person is affected by two or more chronic diseases and is present in 62% to 94% of people over 65 years of age, depending on the study methodology [2,3]. Multimorbidity in old age somatically includes, in particular, arterial hypertension, ischemic heart disease, permanent pain conditions, and chronic renal insufficiency. Depression and dementia are the most common psychiatric disorders in geriatrics [4].

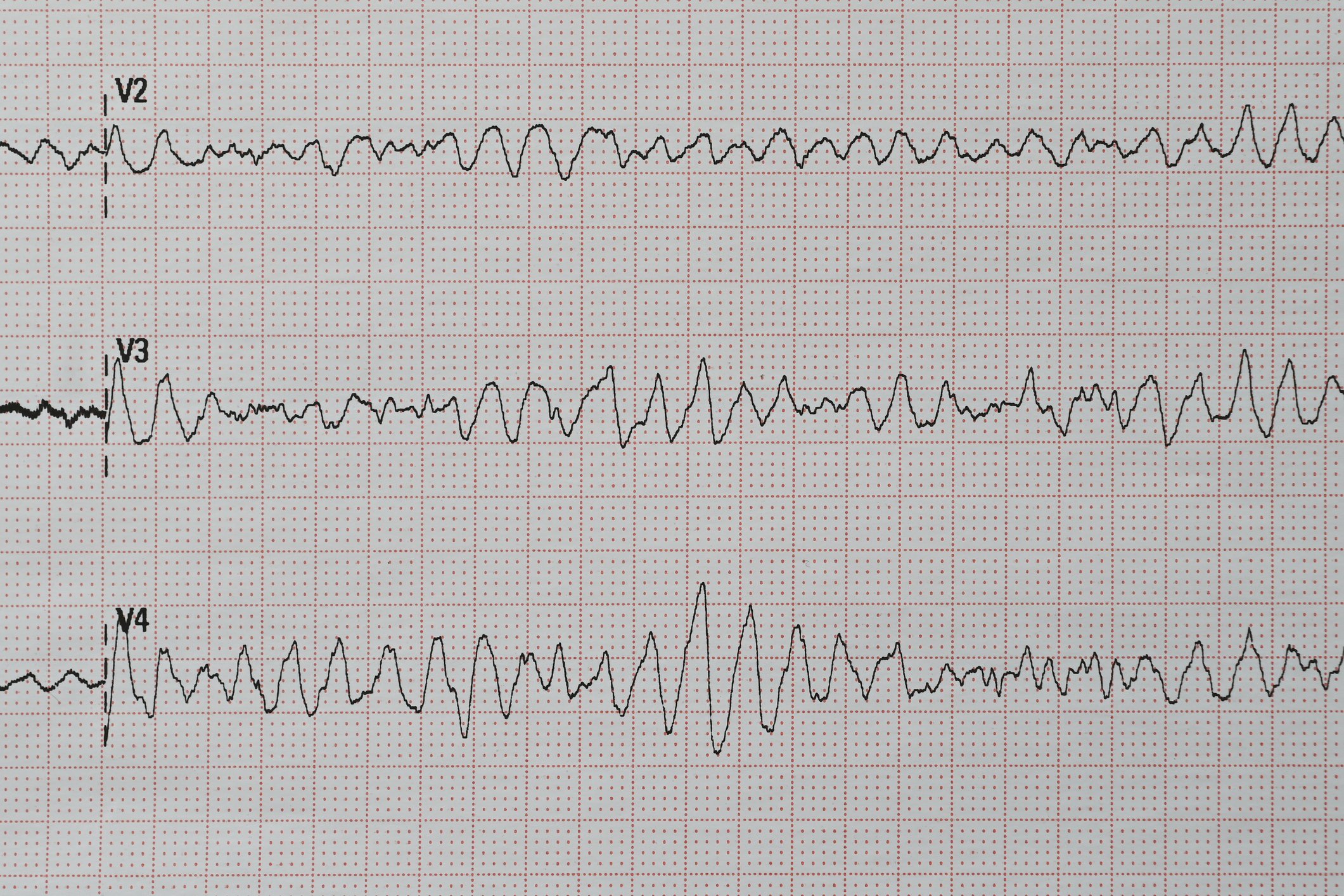

Pharmacological interactions are in turn a consequence of multimorbidity-related polypharmacy [5] (Fig. 1) . In this respect, it is important to know the advantages and disadvantages of polypharmacy and the possible interaction-related consequences of pharmacotherapy in older people with mental illnesses in order to be able to derive and limit particular risks in good time.

Biology of aging and physiological changes

The biological changes of aging represent a complex and individual process. In molecular terms, it involves oxidative stress, as a result of which deletive changes occur in the molecular structure of DNA, proteins, lipids, and prostaglandins [6]. Mitochondrial alterations, telomere shortening, apoptosis, inflammation, and genetic changes with an increase in mutations contribute to a modification of cellular properties that can promote, trigger, or accelerate the development of disease.

Therefore, the aging process is associated with extensive changes in physical physiology: thus, delayed gastrointestinal motility causes increased gastrointestinal absorption or reabsorption capacity [7]. The body fat content increases, at the same time the water content decreases by 10-20% and also the muscle mass decreases significantly. This means that the volume of distribution for lipophilic psychotropic drugs, e.g. benzodiazepines or tricyclic antidepressants, increases with the risk of delayed onset of action and accumulation, while at the same time the concentration of water-soluble substances increases [8].

The main pharmacokinetic changes involve the kidney and liver. Due to increasingly impaired renal function with age due to decrease in nephrons and reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR), hydrophilic substances are excreted by the kidneys to a lesser extent, requiring dose adjustment of predominantly renally eliminated substances, e.g., lithium or amisulpride.

Age-related reduction in hepatic biotransformation results firstly from a 25-35% reduction in volume [9], and secondly from reduced hepatic blood flow of up to 40% [10,11], resulting in a reduction in cytochrome P-450 enzyme activity of up to 30% and impairment of oxidative metabolism [12]. In addition, plasma protein content is decreased resulting in increased concentration and toxicity of substances that are strongly bound to albumins, e.g., benzodiazepines [13].

Pharmacodynamically, changes are found in the area of neurotransmission for almost all neurotransmitter systems with a decrease in cell number, decreased receptor density, and a reduction in neurotransmitter synthesis. In the cholinergic system, there is increased sensitivity to peripheral and central anticholinergic symptoms with drugs that have an anticholinergic profile, e.g., tricyclic antidepressants [14]. Changes in the noradrenergic system are manifested, for example, in increased cardiovascular sensitivity to antagonists of beta-adrenergic receptors, resulting in orthostatic hypotension when co-medicated with antihypertensive drugs, which can lead to dizziness to collapse. Also, an increased vulnerability for acute extrapyramidal motor effects, e.g., dystonia, must be assumed with the use of selective dopamine antagonistic substances. Finally, the brain of the elderly is generally more vulnerable to substances that directly affect central nervous functions, e.g., psychotropic drugs or analgesics. For example, the use of acetyl cholinesterase inhibitors can lead to an increase in the effect of digoxin or beta-blockers, resulting in life-threatening bradycardia. N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists, e.g., memantine, may potentiate the effects of hydrochlorothiazide, L-dopa, antipsychotics, or MAO inhibitors by affecting tubular secretion.

Multimorbidity

Multimorbidity is defined as the simultaneous and persistent presence of at least two chronic diseases and affects more than 2/3 of the elderly, more than half of people over 65 years old have at least three chronic diseases, among which the most common are arterial hypertension, osteoarthritis, ischemic heart disease and diabetes mellitus. It is estimated that by 2035, the number of people who have two or more chronic conditions will be up to 86.4% with the largest increase for cancer and diabetes.

Age does not per se pose a risk for adverse drug reactions, however, between 18% and 47% of people over the age of 65 can be expected to take more than 5 medications and more than 10% even take more than 10 medications [15,16]. The older patients are and the more medications they take, the greater the likelihood of inpatient hospitalization. Up to 16% of hospitalizations are related to medication-related adverse events, which are often the result of comorbidities and resulting polypharmacy. Furthermore, it is problematic that adverse drug reactions are usually more severe in older people than in younger people; they are reported less frequently and are therefore identified less often. Finally, women have a higher rate of side effects compared to men, presumably because the doses of the individual substances are chosen too high or because immunological reactions are caused.

In view of advanced age, multimorbidity and a resulting polypharmacy, knowledge of the pharmacological profile of the prescribed individual substances is just as important as the interaction behavior of two or more substances in order to minimize or, if possible, exclude interaction risks. Polypharmacy need not be disadvantageous per se [17], but can also offer comprehensible advantages in view of multimorbidity requiring treatment. It becomes particularly problematic when indicated polypharmacy for the treatment of several diseases is inadequate or not accepted at all. However, polypharmacy in the elderly is often associated with an increasing risk of adverse side effects or toxicity [18].

Polypharmacy

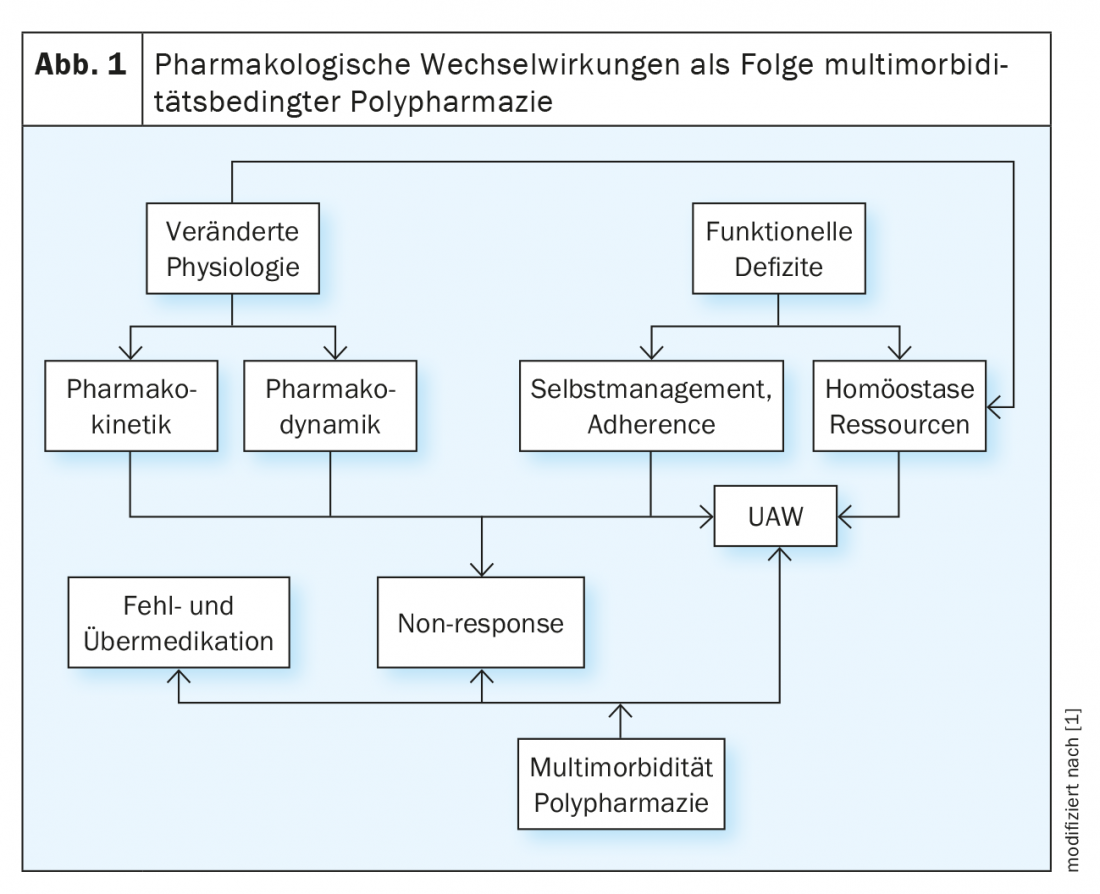

Although there are a variety of different definitions [19,20], generally the term polypharmacy is associated with the persistent concurrent use of five or more medications [21]. Negative consequences of polypharmacy include pharmacologic interactions, cognitive impairment, falls and fractures, long-term and repeated hospitalizations, reduced quality of life, or death [22] (Fig. 2).

The prevalence for polypharmacy in the elderly is reported to be as high as 60% [24]. A survey in Northern Ireland found that 18.3% of people over 65 were taking a dangerous combination of drugs [25]. A strong association of increased mortality and problematic combination treatments emerges particularly with psychotropic drugs, especially benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, and Z-type hypnotics [26]. A study from the United States found a 1.8-fold increase in mortality in people taking an irrational combination of drugs [27].

Drug-diet interactions can also be significant: various antihypertensives, e.g., thiazide diuretics or angiotensin receptor blockers, ACE inhibitors, or potassium-sparing diuretics can lead to zinc deficiency; proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and metformin often cause vitamin B12 deficiency; and vitamin C deficiency sometimes results from taking high doses of aspirin.

Falls and fractures are common causes of morbidity and mortality in the elderly. These quality-of-life impairments may be the result of adverse drug reactions or combination treatment with sedatives, antidepressants, antipsychotics, or antiparkinsonian medications. Approximately 50% of these substances that promote fall risk are substrates of cytochrome P450 enzymes 2C19 or 2D6.

In an observational study, serum concentrations of psychotropic drugs were recorded in elderly patients on admission to a geriatric psychiatric inpatient facility [28]. A total of 236 pa-tients were included. Drug use, patient characteristics, and diagnoses were recorded, and serum analysis for a total of 56 psychotropic drugs was performed in 233 of the patients. In 11% of the pa-tients, the drugs reported as taken were not detectable in the serum at all. Psychotropic drug polypharmacy, defined here as the use of three or more psychotropic drugs, was found in 47% of patients.

However, there are also examples of beneficial combination treatments in geriatric psychiatry. For example, a placebo-controlled study in people with moderate-to-severe dementia found that after 24 weeks of treatment, the verum group had significantly better clinical scores for cognition, clinical global impression, and daily living skills after adding memantine to donepezil compared with the placebo group. However, confusion occurred significantly more often compared with the placebo group (7.9% versus 2.0%) [29].

In contrast, in another randomized controlled trial of people who had moderate to severe AD, there were no additional benefits of combination treatment compared with the respective monotherapy [30].

In a large Scandinavian cohort study examining polypharmacy with antipsychotics with antipsychotic monotherapy in schizophrenic patients, in which the proportion over 65 years of age was 15.3%, benefits included combination treatment of clozapine with aripiprazole, clozapine with a depot antipsychotic, or clozapine with risperidone [31].

In the phase prophylaxis of bipolar affective disorders, the currently valid S3 guideline recommends the combination therapy valproate plus quetiapine, valproate plus ziprasidone, valproate plus lithium, lithium plus quetiapine, or lithium plus ziprasidone if there is no response to monotherapy [32].

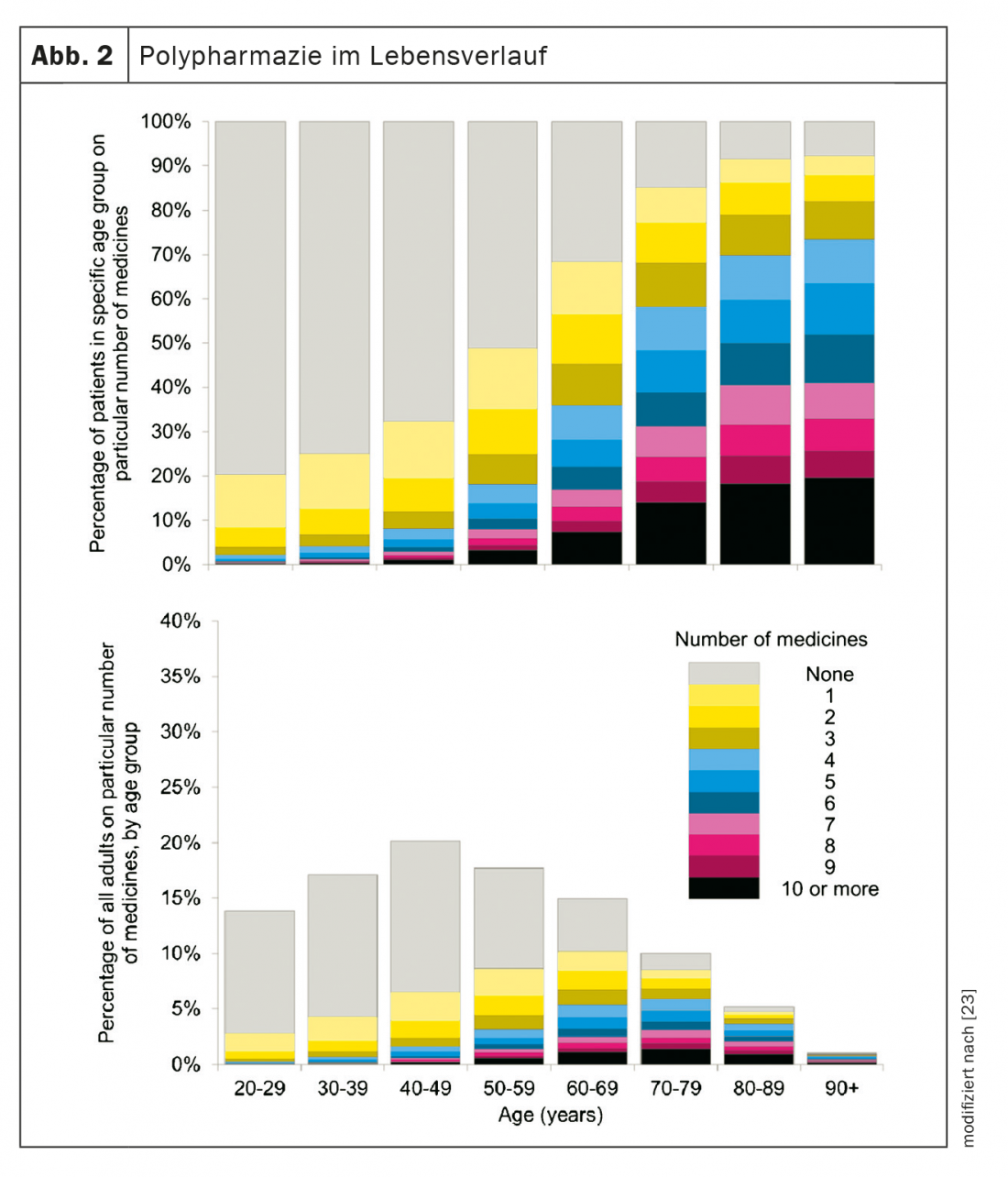

In a retrospective review of approximately 27 400 inpatients, the psychotropic drugs melperone, bupropion, and duloxetine, all of which are considered moderate to strong inhibitors of the hepatic CYP2D6 enzyme, were most notably identified with regard to potential pharmacologic interactions. A major inducer of the CYP3A4 enzyme is known to be carbamazepine, for which there is therefore hardly any indication in the treatment of mental illness [33].

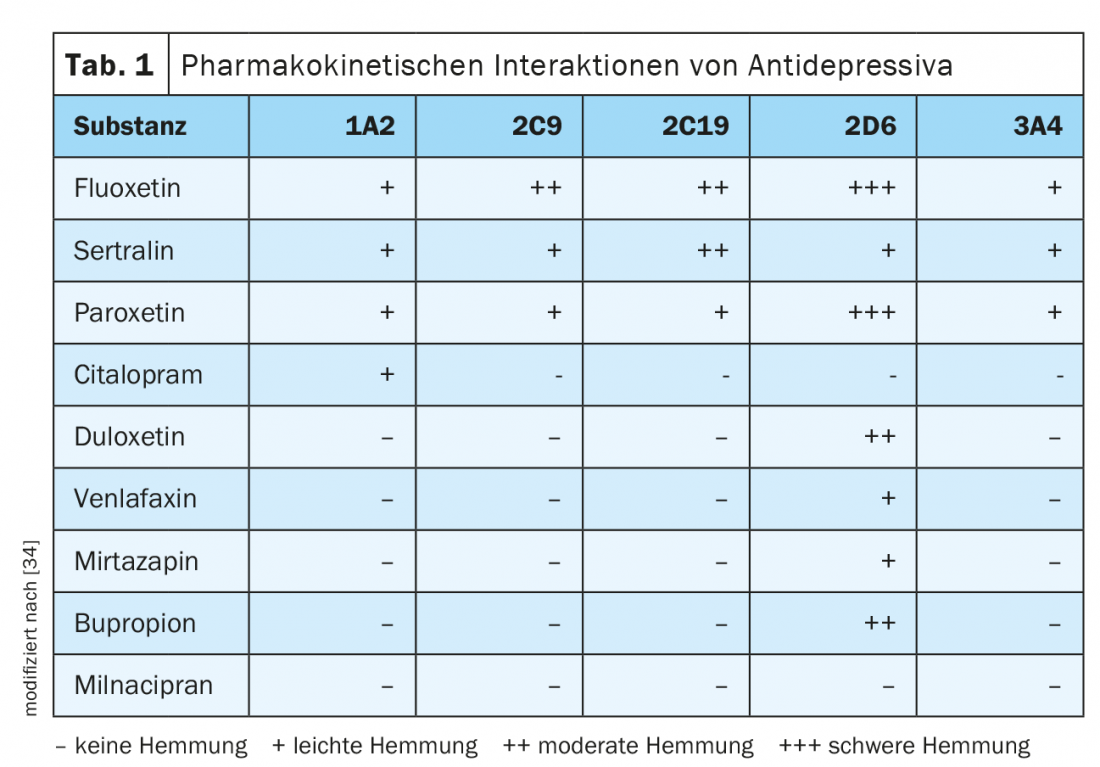

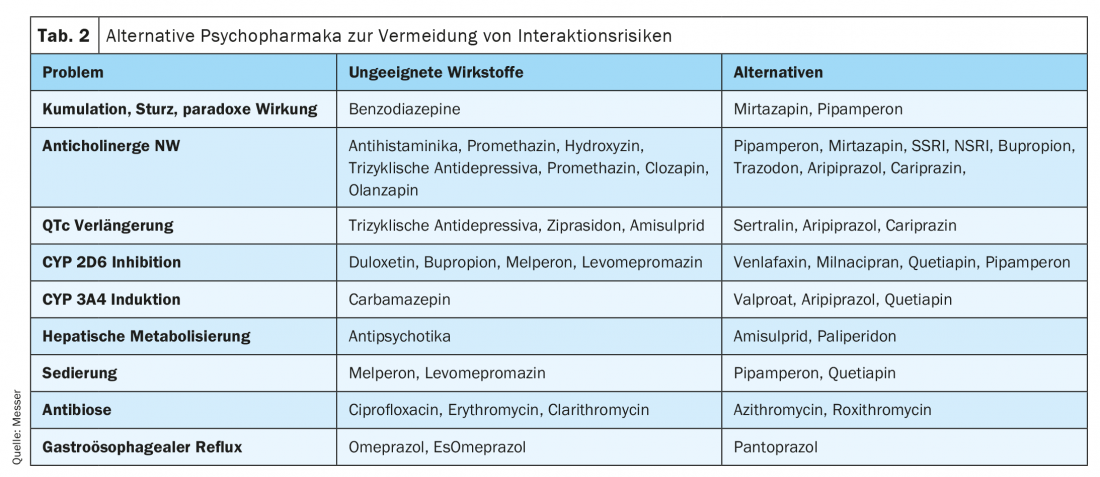

Another retrospective cross-sectional analysis (n=94) of hospitalized elderly aged 60 to 69 years found an increased risk of QTc interval prolongation with, among others, combinations of chlorpromazine with promethazine, haloperidol, or ketoconazole; promethazine plus haloperidol; risperidone plus haloperidol; haloperidol plus ketoconazole; and combinations of ziprasidone with amitriptyline, haloperidol, or chlorpromazine (Tab. 1, Tab. 2).

In principle, every initiation of pharmacotherapy is based on an assessment of the expected success and a risk-benefit ratio. This should always be critically reviewed, especially in long-term therapy. In order to minimize polypharmacy in multimorbidity or to realize a prioritization of therapy on a rational basis, a differentiating evaluation of the pharmaceuticals and the pharmacotherapeutic strategy is therefore required [1].

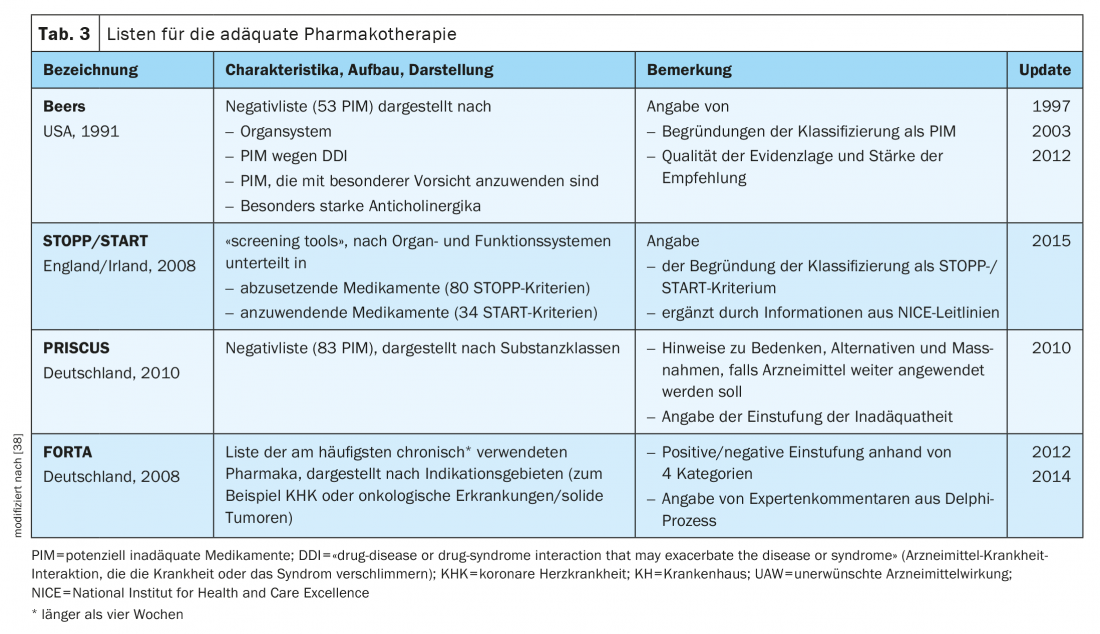

For such a risk assessment with the aim of risk minimization, a number of lists exist, of which the PRISCUS list [35] and the FORTA list [36] are the best known in Germany and are therefore most frequently used (Table 3).

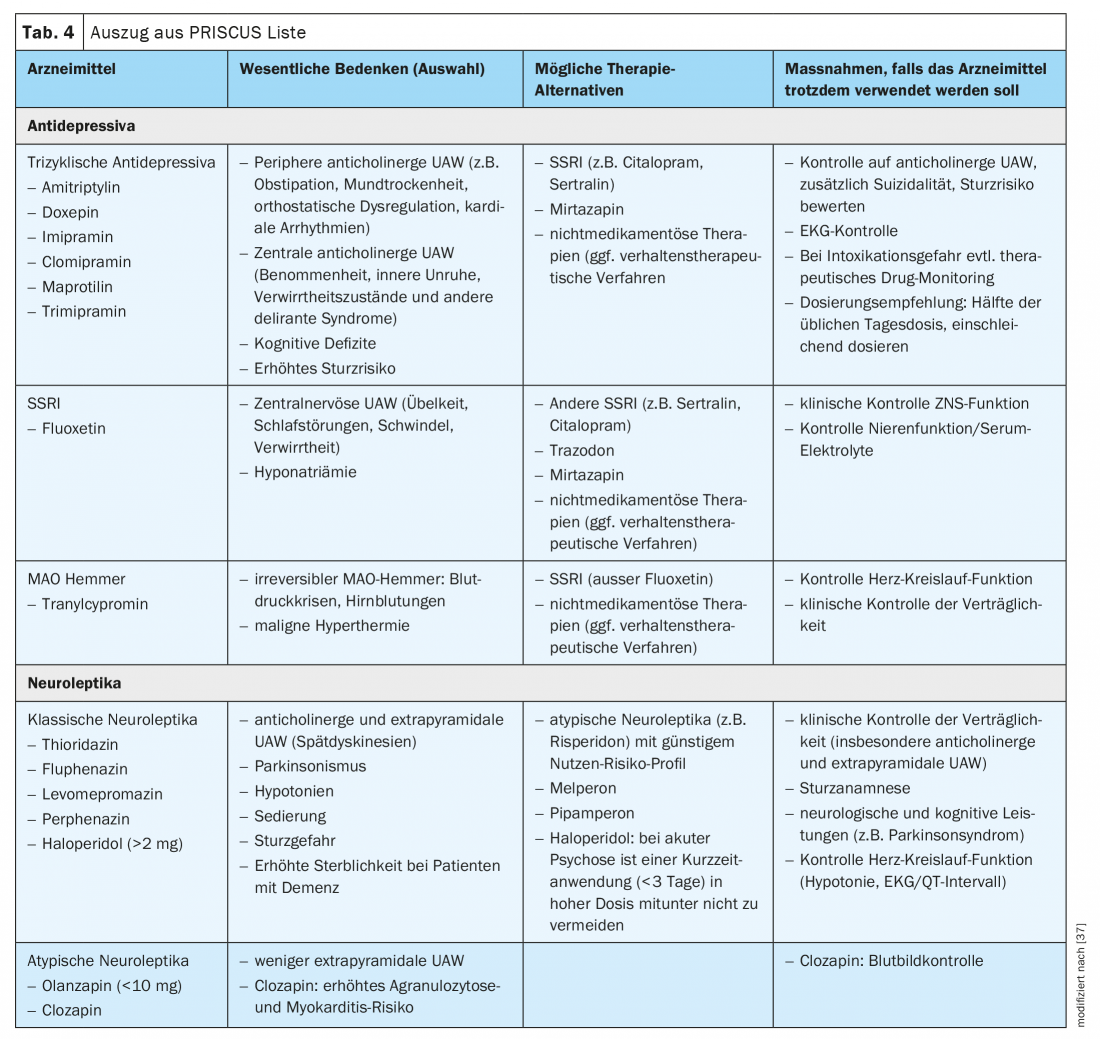

The PRISCUS list was modeled on the US Beers list, first published in the US in 1991, which lists such drugs that are considered risky in the treatment of geriatric patients [37]. The PRISCUS list represents a list of frequently prescribed medications for the elderly that may be of concern, transferred to Germany, and includes over 80 medications that may be unsuitable for elderly patients, possible therapeutic alternatives to these substances, and other recommendations for clinical practice. This list does not claim to be exhaustive, nor does it replace a risk-benefit assessment based on the individual patient; rather, it is intended to draw attention to particular problems in drug therapy for the elderly. Therefore, not only the risky drugs and their possible side effects are listed, but also harmless alternatives are mentioned (Tab. 4).

The FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) list provides an overview of both unfit and proven useful medications for elderly patients. On the basis of studies and expert opinions, various therapeutic methods with 296 substances or substance classes have been evaluated for 30 indication areas in the treatment of age-related clinical pictures. The evaluation of the medicines is carried out in 4 categories. Evaluation criteria are: Patient compliance, age-related tolerability, frequency of contraindications. The drugs are classified as follows:

- Category A (essential): Drug has already been tested in older patients in larger studies, benefit assessment is clearly positive.

- Category B (beneficial): Efficacy has been demonstrated in elderly patients, but there are limitations to safety and efficacy.

- Category C (questionable): There is an unfavorable benefit-risk ratio for elderly patients. Close monitoring of effects and side effects is required. If more than 3 drugs are taken at the same time, it is recommended to omit these drugs first. The physician should look for alternatives.

- Category D (avoid): These drugs should almost always be avoided. The doctor should find alternatives. Most substances from this group are usually also found on negative lists such as the PRISCUS list.

Further information is available on the website www.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/klinische-pharmakologie/forschung/forta-projekt-deutsch, from which the current version (2018) can be downloaded. The FORTA list the first positive-negative evaluation of drugs for the treatment of elderly patients, has now been digitized. This list not only indicates the drugs that are unsuitable for elderly patients, as in a purely negative list, but also names the drugs that have been proven to be useful, i.e. it is also a positive list.

Conclusion

Pharmacotherapy of the elderly requires prudence, best pharmacological expertise and a differentiated approach. The changed conditions in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics require an individualized substance selection and a disorder- and situation-appropriate dosage. Polypharmacy due to comorbidities or resistance to therapy must always be evaluated on a case-by-case basis and critically in terms of benefits and risks.

Take-Home Messages

- The biology of aging is accompanied by widespread physiological changes that may have pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic implications.

- Older people with psychiatric illnesses have a higher

- risk for adverse drug reactions, which is caused by both age and multimorbidity.

- Polypharmacy in the treatment of mentally ill older people is predominantly the result of age-related multimorbidity.

- Therefore, knowledge of somatic diseases and their pharmacotherapy on the one hand and the interaction behavior of indicated psychotropic drugs on the other hand is just as important for the treatment of the elderly.

- Well-evaluated and valid instruments (Priskus list, Forta list) are available in German-speaking countries for risk assessment with the aim of risk limitation.

Literature:

- Wehling M, Burkhardt H: Medicinal therapy for the elderly. 2019: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Knottnerus JA: Comorbidity or multimorbidity. European Journal of General Practice, 1996. 2(2): 65-70.

- Violan C, et al: Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of observational studies. PLoS One, 2014. 9(7): e102149.

- McLean G, et al: The influence of socioeconomic deprivation on multimorbidity at different ages: a cross-sectional study. Br J Gen Pract, 2014. 64(624): e440-447.

- Tveito M, et al: Correlates of major medication side effects interfering with daily performance: results from a cross-sectional cohort study of older psychiatric patients. Int Psychogeriatr, 2016. 28(2): 331-340.

- Harman D: Free radical involvement in aging. Pathophysiology and therapeutic implications. Drugs Aging, 1993. 3(1): 60-80.

- Orr WC, Chen CL: Aging and neural control of the GI tract: IV. Clinical and physiological aspects of gastrointestinal motility and aging. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2002. 283(6): G1226-1231.

- Pea F: Pharmacokinetics and drug metabolism of antibiotics in the elderly. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol, 2018. 14(10): 1087-1100.

- Schmucker DL: Liver function and phase I drug metabolism in the elderly: a paradox. Drugs Aging, 2001. 18(11): 837-851.

- Wynne HA, et al: The effect of age upon liver volume and apparent liver blood flow in healthy man. Hepatology, 1989, 9(2): 297-301.

- Le Couteur DG, McLean AJ: The aging liver. Drug clearance and an oxygen diffusion barrier hypothesis. Clin Pharmacokinet, 1998. 34(5): 359-373.

- Tan JL, et al: Age-Related Changes in Hepatic Function: An Update on Implications for Drug Therapy. Drugs Aging, 2015. 32(12): 999-1008.

- Valerio C, et al: Human albumin solution for patients with cirrhosis and acute on chronic liver failure: Beyond simple volume expansion. World J Hepatol, 2016. 8(7): 345-354.

- Lange-Asschenfeldt C, Benkert O: Psychotropic drugs in old age and internal diseases, in Compendium of Psychiatric Pharmacotherapy, O. Benkert and H. Hippius, Editors. 2018, Springer: Berlin Heidelberg. 937-950.

- Kim J, Parish AL: Polypharmacy and Medication Management in Older Adults. Nurs Clin North Am, 2017. 52(3): 457-468.

- Nascimento R, et al: Polypharmacy: a challenge for the primary health care of the Brazilian Unified Health System. Rev Saude Publica, 2017. 51(suppl 2): 19s.

- Payne RA, et al: Is polypharmacy always hazardous? A retrospective cohort analysis using linked electronic health records from primary and secondary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2014. 77(6): 1073-1082.

- Field TS, et al: Risk factors for adverse drug events among nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med, 2001. 161(13): 1629-1634.

- Masnoon N, et al: What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr, 2017. 17(1): 230.

- Mortazavi SS, et al: Defining polypharmacy in the elderly: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open, 2016. 6(3): e010989.

- Rankin A, et al: Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2018. 9(9): Cd008165.

- Caughey GE, et al: Increased risk of hip fracture in the elderly associated with prochlorperazine: is a prescribing cascade contributing? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf, 2010. 19(9): 977-982.

- Payne RA, et al: Prevalence of polypharmacy in a Scottish primary care population. Eur J Clin Pharmacol, 2014. 70(5): 575-581.

- Borchelt M, Steinhagen-Thiessen E: Ambulatory geriatric rehabilitation – assessment of current status and prospects. Z Gerontol Geriatr, 2001. 34 Suppl 1: 21-29.

- Ryan C, et al: Potentially inappropriate prescribing in an Irish elderly population in primary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2009. 68(6): 936-947.

- Counter D, Millar JWT, McLay JS: Hospital readmissions, mortality and potentially inappropriate prescribing: a retrospective study of older adults discharged from hospital. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2018. 84(8): 1757-1763.

- Muhlack DC, et al: The Association of Potentially Inappropriate Medication at Older Age With Cardiovascular Events and Overall Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2017. 18(3): 211-220.

- Tveito M, et al: Psychotropic medication in geriatric psychiatric patients: use and unreported use in relation to serum concentrations. Eur J Clin Pharmacol, 2014. 70(9): 1139-1145.

- Tariot PN, et al: Memantine treatment in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer disease already receiving donepezil: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 2004. 291(3): 317-324.

- Howard R, et al: Donepezil and memantine for moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med, 2012. 366(10): 893-903.

- Tiihonen J, et al: Association of Antipsychotic Polypharmacy vs Monotherapy With Psychiatric Rehospitalization Among Adults With Schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry, 2019.

- Bauer M, et al: S3-Leitlinie zur Diagnostik und Therapie Bipolarer Störungen. 2020: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Hefner G, et al: Prevalence and sort of pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions in hospitalized psychiatric patients. J Neural Transm (Vienna), 2020. 127(8): 1185-1198.

- Kratz T, Diefenbacher A: Psychopharmacological treatment in older people. Deutsches Aerzteblatt Online, 2019.

- Holt S, Schmiedl S, Thürmann PA: Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: the PRISCUS list. Dtsch Arztebl Int, 2010. 107(31-32): 543-551.

- Kuhn-Thiel AM, et al: Consensus validation of the FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) List: a clinical tool for increasing the appropriateness of pharmacotherapy in the elderly. Drugs Aging, 2014. 31(2): 131-140.

- Beers MH: Explicit criteria for determining potentially inappro-priate medication use by the elderly. An update. Arch Intern Med 1997; 157: 1531-1536.

- Mosshammer D, et al: Polypharmacy-an Upward Trend with Unpredictable Effects. Dtsch Arztebl Int, 2016. 113(38): 627-633.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2021; 19(3): 6-11.