Epidermal-growth-factor receptors are found in the skin and sebaceous glands, tyrosine kinase (TK) in keratinizing skin, mucous membranes and hair, and are thus also targets of EGFR- and TK-inhibiting oncologics (TKIs). The majority of patients on TKI therapy thus suffer from side effects to the skin and hair; the changes can be so drastic that they lead to interruption or discontinuation of the valuable therapy. Better knowledge of these drugs, training of professionals in oncology and dermatology, with prophylaxis and patient training could counteract this and improve acceptance and treatment success.

The advent of newer oncology drugs that specifically block markers, receptors and signals has long since taken place. Since around the 1990s, it has been known that dysregulated tyrosine kinases (TK) often play a key role in the development of tumor diseases. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are therefore playing an increasingly important role in tumor therapy. Replacing or supplementing toxic chemotherapeutic agents with these new substances is very successful, but, as far as the skin is concerned, it is also fraught with side effects. Epidermal-growth-factor receptors are found in skin and sebaceous glands, tyrosine kinase in keratinizing skin, pigmenting cells, mucous membranes, and hair; thus, they are also targets of EGFR- and TK-inhibiting oncologics.

The TKIs are a very heterogeneous group and in some cases also show inhibition on various TK, so-called “multiple tyrosine kinase inhibitors”. Each TKI has its own spectrum of side effects. Areas of application or have an approval

- Sunitinib for renal cell carcinoma and GIST.

- Sorafenib for renal cell and hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), BCR-ABL-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and more.

- Lapatinib for HER2-positive breast carcinoma

- Erlotinib for non-small cell lung cancer and pancreatic cancer.

- Gefitinib for non-small cell lung cancer with activating EGFR mutations.

- Pazopanib for renal cell carcinoma and sarcomas

- Nilotinib, dasitinib (and BCR-SBL pos. ALL), bosutinib, ponatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia.

- Gefitinib and critozinib for non-small cell lung cancer (gefitinib: with activating EGFR mutations, critozinib: ALK-positive TU).

In the following, the preparations are listed which particularly frequently show skin side effects.

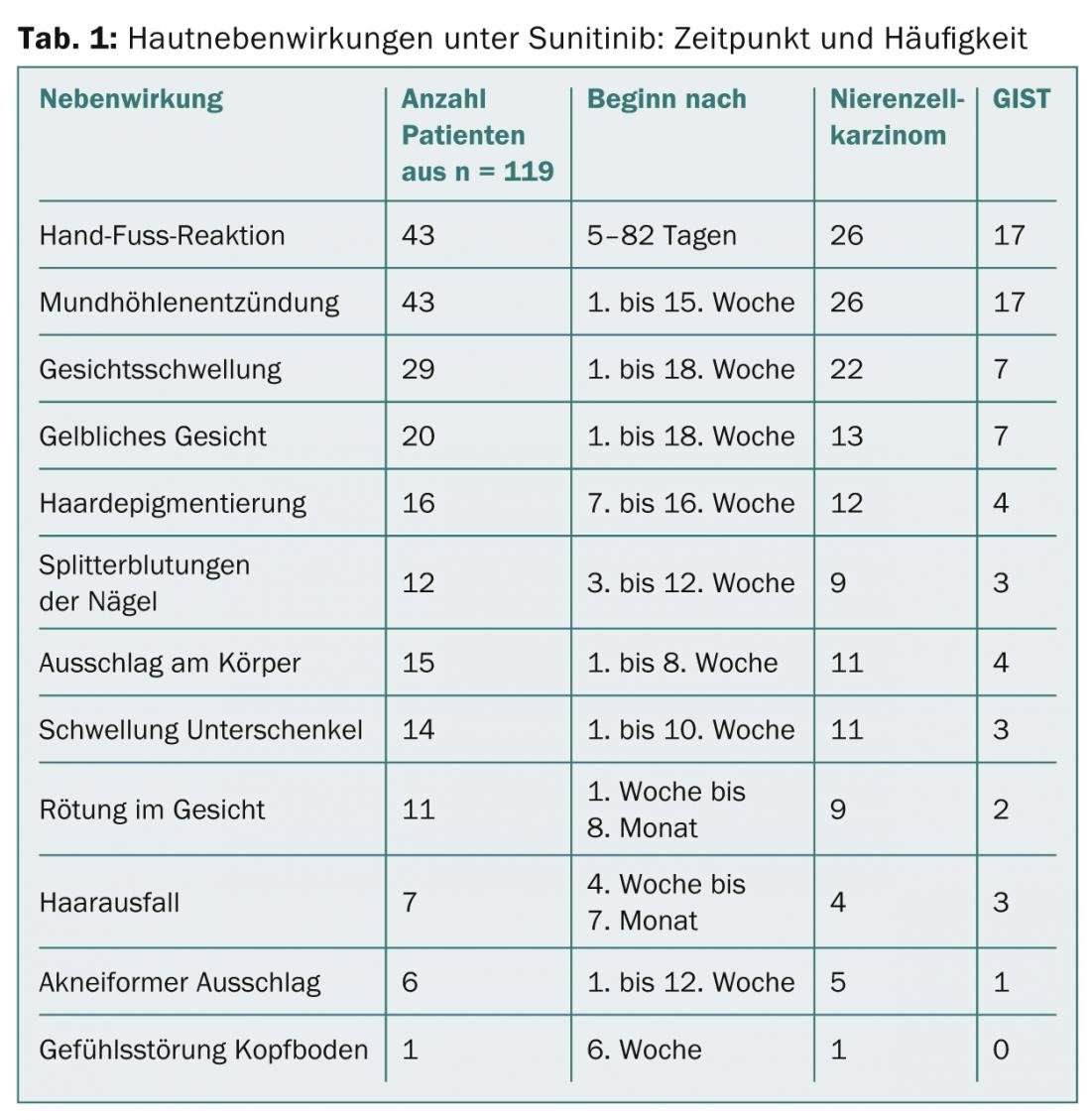

Sunitinib (Sutent®): The most common effect on the skin is the development of the hand and foot reaction (Fig. 1), which already occurs after 5 to 42 days and in almost 50% of those treated (Tab. 1).

Mucositis is the second most common side effect, and there is often facial swelling in the 1st to 18th week. Specifically with sunitinib, a yellowish coloration and disturbances in the pigmentation of the hair are observed. Here, so-called tiger hairs occur, because during the therapy cycles the hairs depigment and during the therapy breaks they produce the normal color again, which leads to a characteristic stripe pattern. Splinter hemorrhages and dystrophy of the nails (Fig. 2), papular eczema on the trunk, and hair loss are noted in approximately 10% of patients. Phenomena include loss of lentigines and of seborrheic keratoses, which also strongly express TK.

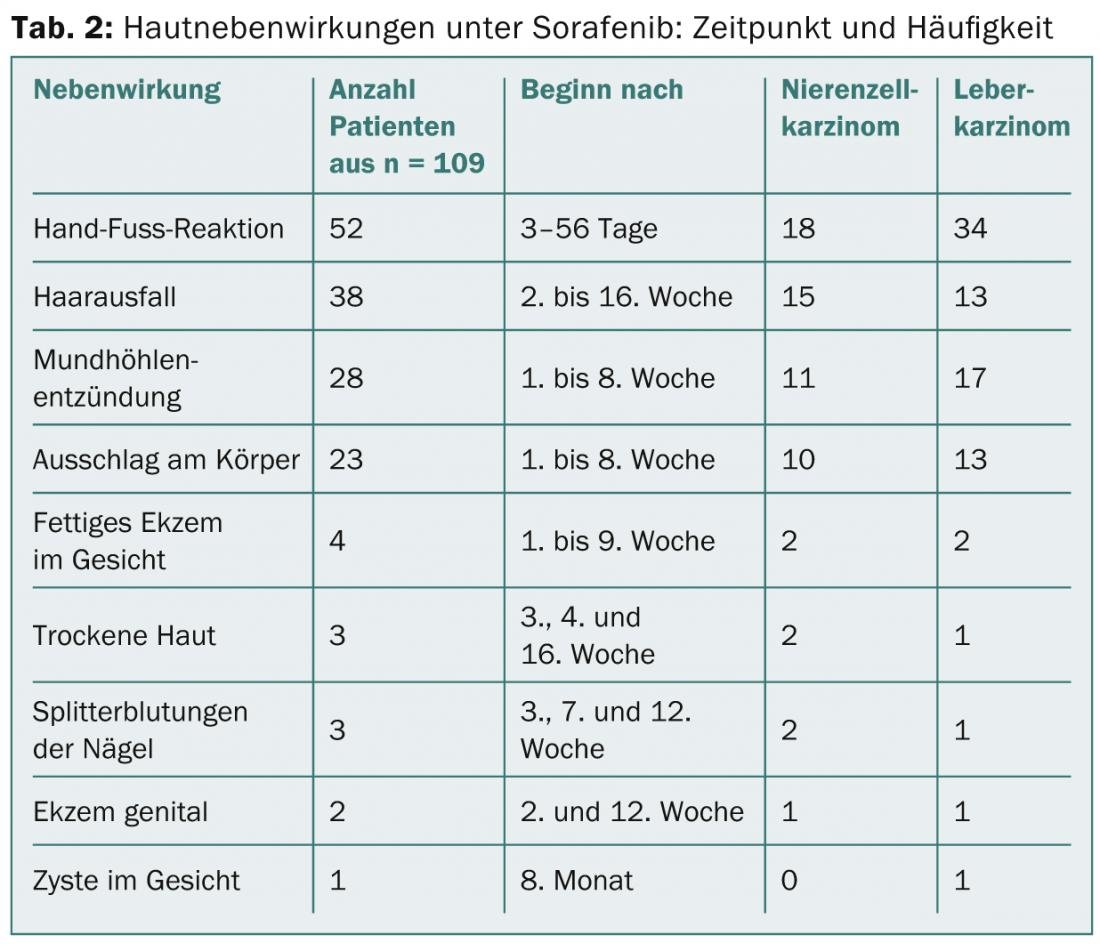

Sorafenib (Nexavar®): Again, painful, inflammatory calluses are the most common complaint in half of patients. One-third experience diffuse effluvium, which may persist into the 16th week, and one-fourth experience rash on the body (Fig. 3) or oral sinusitis (Table 2) . Xerosis of the skin and eczema appear to occur more frequently than with sunitinib.

imatinib (Gleevec®): The most frequent side effect on the skin is orbital edema, which starts relatively early and often persists throughout the entire therapy (Fig. 4). Already after five to six weeks, they begin, sometimes quite violently, with erythema and scaling, a picture which resembles a contact allergy. Fortunately, the edema is later only faintly present, but it means a change in appearance that is difficult for those affected to accept. Therapeutically, locally weak steroids and cooling compresses with Aqua d’Alibour can help in the acute stage. Very frequent (approx. 65%) is also the partly generalized xerotic eczema (tab. 3, fig. 5), which often requires dermatological treatment. Itching is also a frequently observed side effect during therapy with imatinib. Rarity is a rash called pityriasis rosea.

The changes and their therapy in detail

Palmoplantar keratosis: hand and foot reaction is very common under TKIs, especially sorafenib and sunitinib, and is one of the prominent skin problems. First, the analogy was made to chemotherapy-induced palmoplantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome; however, it is actually a new entity associated with callositas at the palmae and plantae sites of pressure, painfulness, and erythema. The toxic damage to the skin that occurs under chemotherapeutic agents – single cell necrosis in the epidermis – responds to antioxidants. In contrast, hand and foot reactions under TKI are inflammatory and an exuberant attempt by the skin to repair itself.

The treatment provides for minimizing hyperkeratosis and keeping the skin soft. This is achieved with the use of externals with a salicyl or urea content of ≥5%, also prophylactically. Higher-potency steroid ointments such as mometasone or clobetasol diproprionate, which may be applied palmoplantar daily, are effective against inflammation.

Eczema: Patients under TKI and EGFR inhibition experience a fundamental shift in their skin condition towards xerosis and eczema susceptibility. Not infrequently, and especially with imatinib, erosive eczema develops, which can occasionally become generalized. Regular moisturization of the skin with lipid-replenishing ointments is therefore recommended right from the start of therapy. In cases of xerosis and eczematous skin, the lipid content of topical care should be increased, if necessary with additions of antiseptics such as triclosan 0.5% to 2% and/or barrier-promoting lactic acid, urea or glycerin. Treatment with steroid ointments 1×/day, then twice a week at intervals, is required in the acute stage.

Folliculitis: Very well known are the severe folliculitic changes on the face and trunk with EGFR inhibitors. Although much less common, they are regularly seen even in TKI-treated patients. In addition to avoiding heat and UV exposure, treatment with topical mid- to high-level steroids is an option. This is despite the fact that the changes can be very similar to acne, and steroids on the face should usually be used very cautiously. Additional treatment with steroid-sparing pimecrolimus in cream base is possible and internal treatment with tetracyclines such as minocycline 2 × 50 mg/d is probably effective due to anti-inflammatory properties of these drugs.

Hair: Diffuse effluvium is observed mainly with sorafenib. Theoretically, avoiding heat and sun would be helpful, as with increased circulation in the scalp, TKIs may recognize the hair roots as a (false) target. Apparently, however, the hair loss is of limited duration. Currently, no evidence-based therapy exists.

Other side effects: Overall, the disorders of nails, mucous membranes and skin pigmentation are common. While the appearance of a yellowish complexion under sunitinib or depigmentation of darker skin is unlikely to be prevented, nail trimming and prevention of trauma is helpful. Topical steroids in liquid form can be used against nail dystrophy, also a consequence of increased signal detection by TKIs and associated inflammation. For the mucous membranes, concomitant measures such as rinsing with antiseptics like chlorhexidine help against superinfections, and an effective therapy could be the application of tacrolimus ointment. Although there is broad experience for most of the proposed therapies, there are no studies for which there is an urgent need to catch up.

Prophylaxis

Prophylaxis includes UV protection in case of increased sensitivity of the skin to sun rays. Mechanical protection of hands and feet against injuries and resulting wound healing disorders and risk of infections is as much a part of this as wearing soft shoes and regular care of hands and feet with creams containing urea to prevent painful callus formation. Friction-intensive activities at work, around the house and garden should be kept to a minimum during therapy cycles and gloves should be worn. As with diabetic foot precautions, pressure points in the shoes should be avoided. However, the rest of the integument also requires regular re-lubrication, as the skin becomes increasingly xerotic with the continuation of TKI therapy, often irreversibly. The nails should be cut short.

Conclusion

The majority of patients on TKI therapy suffer from side effects to the skin and hair; the changes can be so drastic that they lead to interruption or discontinuation of the valuable therapy. Better knowledge of these new drugs, training of oncology professionals and dermatologists could counteract this. Here, prophylaxis and information of the patient play a decisive role; this simultaneously promotes the acceptance of the therapy and the oncological therapy success.

Literature list at the author

Mark David Anliker, MD

InFo Oncology & Hematology 2014; 2(1): 16-20.