The annual symposium for general practitioners and gynecologists was held in Olten at the end of January. HAUSARZT PRAXIS was on site and reports on the one hand about the problem of medication during pregnancy, and on the other hand about primary and secondary dysmenorrhea.

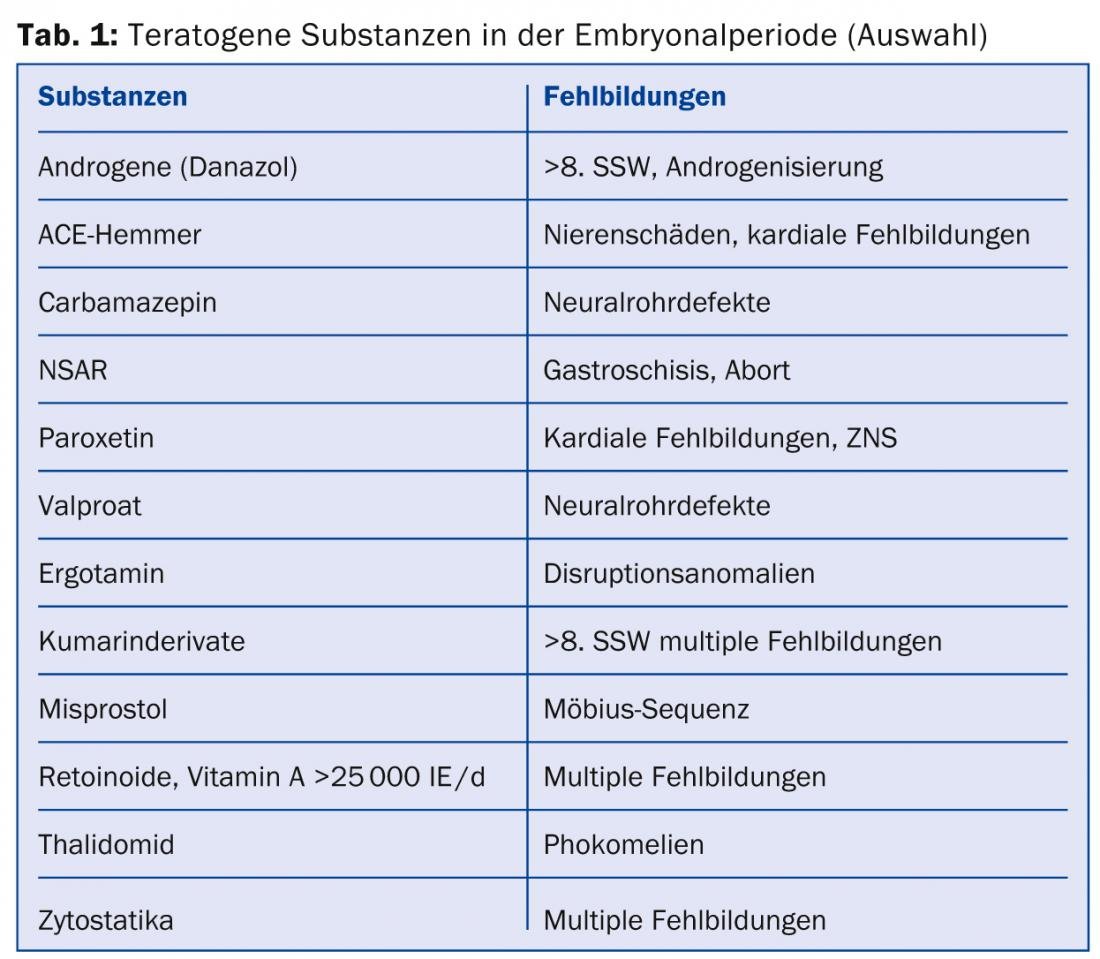

Prof. Dr. med. Irene Hösli from the Clinic for Obstetrics and Pregnancy Medicine in Basel spoke on the topic of “Medications in Pregnancy”. She noted that medication use in pregnant women in the first three months has increased by 60% over the past 30 years. This is mainly due to the increase in maternal chronic diseases with increasing age, increase in BMI, etc. Pregnant women today take up to four different medications during the first trimester, and even up to eight medications during the entire pregnancy, often in self-medication. Malformations occur in 3-6% of all pregnancies, and drugs are the trigger in about 1-5% of cases (Table 1).

Pharmacological substances therefore always involve potential risks for the mother and the unborn child, which must be weighed up depending on the situation. This does not apply to folic acid and vitamin preparations administered as dietary supplements before and during pregnancy to provide optimal support for mother and child.

Prof. Hösli specifically addressed the problem of depression in pregnancy: According to recent data, 3-6% of all pregnant women are treated with SSRIs due to moderate or severe depression. Pregnant women with known depression should definitely continue antidepressant therapy because the relapse rate is very high, she said. The benefit would clearly outweigh the risk here. Taken periconceptually or in the first trimester, there was no increased risk of malformation for either sertraline or citralopram, and a slightly increased risk of cardiac malformation for fluoxetine and paroxetine. Among the tricyclic antidepressants, nortriptyline, lmipramine and amitriptyline are the drugs of choice. In the second trimester or peripartum, adaptation disorders may occur in two to three out of ten newborns on antidepressants, so neonatal monitoring may be necessary. Whether medication should be reduced or discontinued two to four weeks before birth is controversial.

Management of dymenorrhea

Prof. Dr. med. Wolfgang Schöll from the University Clinic for Gynecology at the Inselspital in Bern provided information on the treatment of primary and secondary dysmenorrhea. Primary dysmenorrhea affects the majority of all young girls and women, 60-70%: During menstruation, recurrent, cramp-like lower abdominal pain occurs without any recognizable pathological anatomy. Nausea, vomiting, headache, backache, lightheadedness, and even diarrhea can accompany the cramping abdominal pain that begins hours before menstruation and can last for days.

However, especially in the third and fourth decades of life, progressive secondary dysmenorrhea may then occur with a painful condition during menstruation associated with a pathologically palpable finding in the pelvis, often endometriosis. Müller’s malformations, adenomyosis, fibroids, ovarian cysts, endometrial polyps, adhesions, cervical canal stenosis, recumbent IUDs, genital varicosis, and nongenital changes may be other causes of secondary dysmenorrhea.

The severity of the menstrual pain and the possible obstruction of daily activities defines the use of analgesics. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the first choice, according to Prof. Schöll, with COX-1 inhibitors preferred over COX-2 inhibitors. In particularly severe cases, therapy can begin the day before the expected menstrual period. Mefenamic acid derivatives may be slightly more effective than propionic acid derivatives such as lbuprofen or naproxen, if appropriate. Metamizole, which is not an NSAID and has excellent efficacy for visceral pain, is a good alternative. The use of non-drug approaches such as acupuncture and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is also justified by the evidence, according to Prof. Schöll. If NSAIDs result in inadequate pain control or if anticonception is desired, oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) are used to lower uterine prostaglandin levels and reduce the amount of menstrual blood by suppressing ovulation. ln severe cases, NSAIDs and OCPs may be combined. In secondary dysmenorrhea, which requires further pathological clarification, causal multimodal therapy is necessary.

Séverine Bonini

Source: 32nd Symposium for General Practitioners and Gynecologists, January 30, 2014, Olten.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(3): 34-35