Genetic counseling is voluntary, open-ended, non-directive, and comprehensive. The question is defined by the person seeking advice in his or her personal context. Anamnestic diagnoses must be questioned and checked from a medical-genetic point of view with regard to their plausibility and relevance. The Law on Human Genetic Testing (GUMG) must be taken into account. For complex issues, it is recommended to involve specialists.

In 1975, “genetic counseling” and its contents were first defined by the American Society of Human Genetics. Genetic counseling is a personal communication process that addresses the occurrence or risk of occurrence of a possible genetic disease as well as its differentiation from a non-genetic disease in the person seeking counseling or in his or her family.

Genetic information can have considerable importance for health development and for individuals’ life planning, including their reproductive choices. They can affect not only the patients themselves, but also their partners or other family members. The assessment of genetic characteristics, medical findings including genetic laboratory findings and disease probabilities, as well as counseling before and after genetic testing, is therefore of particular importance.

The following are some aspects important to family medicine practice. Details on genetic counseling in the context of the prescription of genetic examinations are legally regulated in Switzerland by the “Federal Law on Genetic Examinations in Humans” (GUMG), of which every physician performing genetic counseling must be aware. Detailed guidelines on genetic counseling are published by the professional societies for human genetics and medical genetics, respectively.

Indications and procedure of genetic counseling

The indication for genetic counseling is given for all questions that are related to the occurrence or the probability of an (epi-)genetically caused or co-caused disease or developmental disorder. This includes questions related to possible differential diagnoses to non-genetic etiologies. The indication may also be a subjective concern on the part of the person seeking advice, with an assessment of the severity of a condition and the family burden on the person seeking advice. The use of genetic counseling is voluntary.

Typical counseling situations in the practice include the desire of an affected person or family member to obtain information about the disease and their own risk of developing the disease, as well as the risk to offspring. In addition, the person seeking advice expects to receive information about treatment options as well as the various options available for managing risk. This includes the discussion of genetic testing including its indications, significance and limitations. The resulting possibilities of using the genetic information in relation to one’s own personal situation, consequences and decision alternatives, taking into account the personal and family situation of the person seeking advice, should also be discussed. Genetic laboratory tests can be ordered in very different contexts, depending on the question asked, and can have different informative value with regard to a risk of disease. A general distinction is made between diagnostic tests, predictive tests, tests of susceptibility factors, pharmacogenetic tests, tests to determine transmissibility, prenatal tests, preimplantation diagnostics and screening tests.

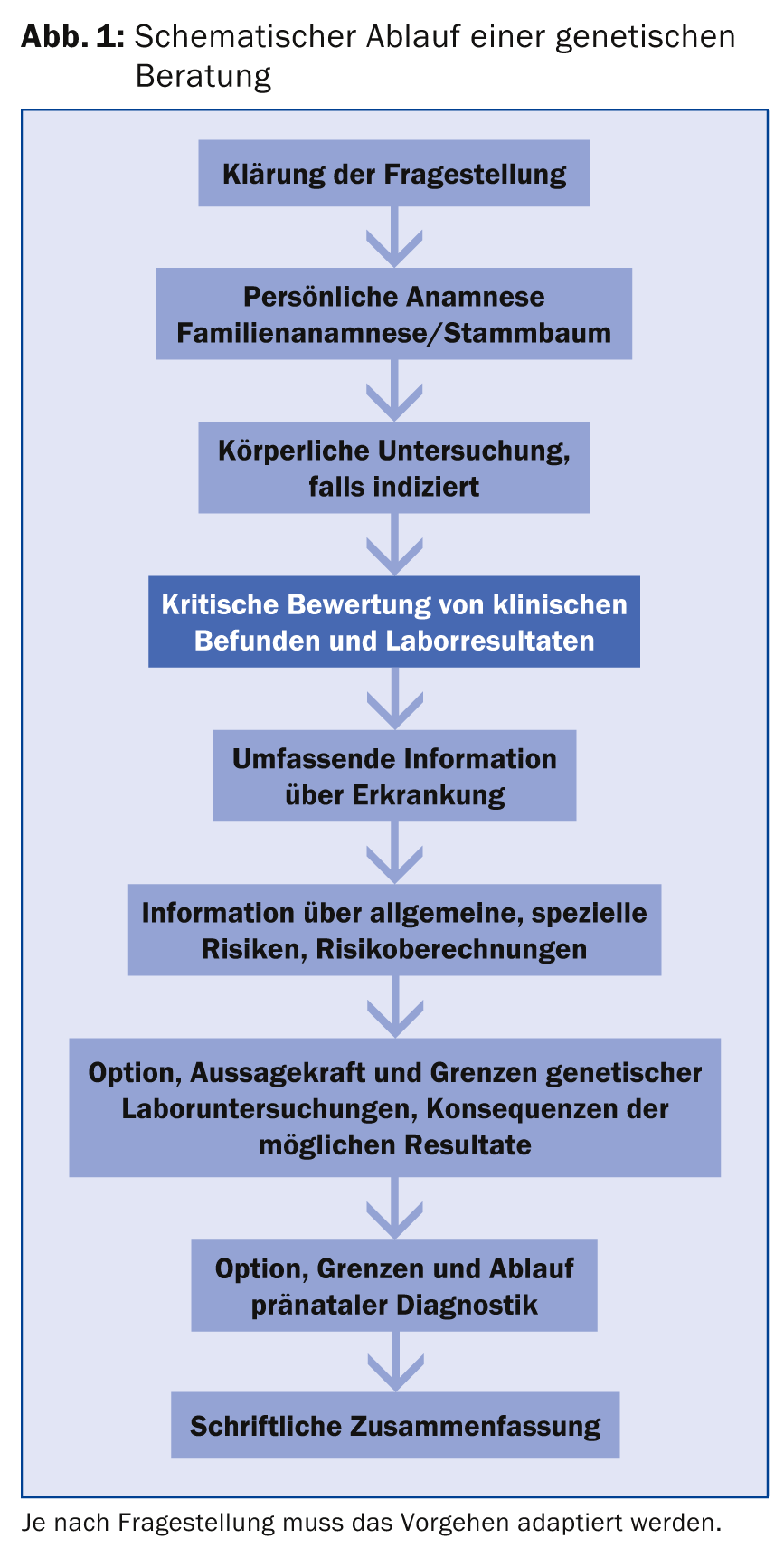

The first and most important task of the consulting physician is therefore to clarify the question of the person seeking advice and to take a detailed personal and family history (family tree spanning at least three generations). Depending on the question, information on previous pregnancies, environmental influences, exposure to harmful substances, diagnostic and/or prophylactic measures already carried out on the person seeking advice or affected relatives must also be collected. If the question relates to a specific illness in the family, the consulting physician must critically question and secure the diagnosis as well as the cause of the illness of the affected person. Findings or anamnestic information that are not self-reported must be considered and reviewed from a medical-genetic point of view with regard to their plausibility and relevance. A schematic consultation flow is outlined in Figure 1 .

Genetic counseling should be conducted in an open-ended and non-directive manner so that the person seeking counseling can subsequently make informed, independent and sustainable decisions, not only but also regarding the use of genetic testing. In particular, the individual values including religious attitudes as well as the psychosocial situation of the patient must be taken into account and respected.

Genetic counseling should generally be documented by providing a summary of the counseling content in plain language to the person seeking counseling. It must be determined with the person seeking advice which physicians will be informed about the counseling that has taken place, the results of genetic examinations and the contents of the counseling.

Common consulting situations

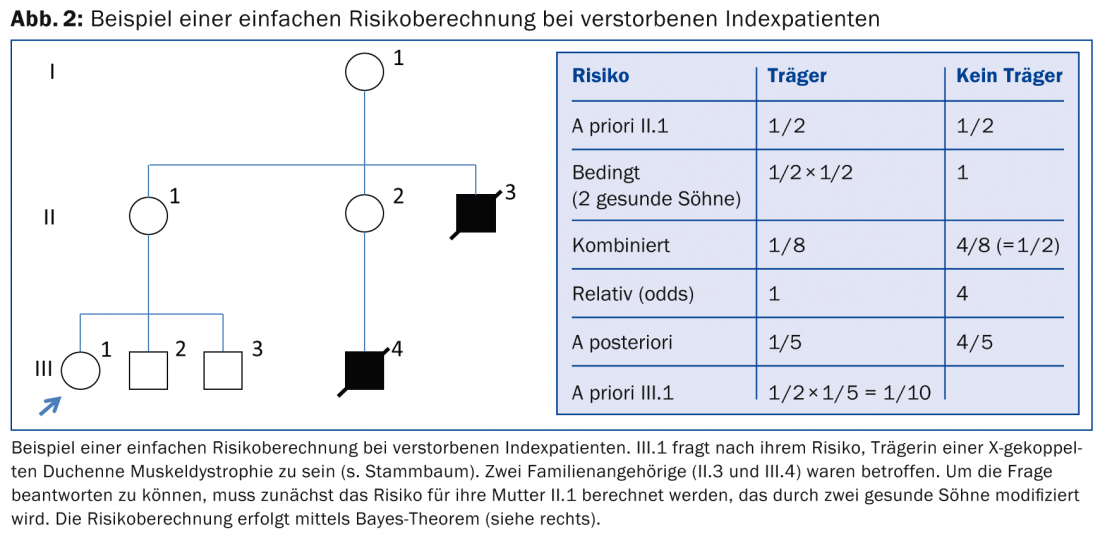

Monogenic diseases: A classic, not uncommon example of a consultation situation for a monogenic disease is the occurrence of cystic fibrosis, a recessive hereditary disease with a prevalence of approximately 1:3200 in the Northern European population. An estimate of disease probabilities will be made, which must take into account degree of relatedness, consanguineousness, ethnicity, incidence, heterozygote frequencies, and mutation probabilities. Here, too, it is first important that the diagnosis of the affected person – also by molecular genetics – as well as the sponsorship of the parents is secured in order to be able to carry out appropriate risk calculations according to the question. With more than a thousand known mutations, the identification of familial mutations also helps to provide information about manifestation and severity as well as treatment options for the disease, which often depend on the type of mutation and its combination. In risk calculations, consanguinity and ethnicity should generally be considered as critical factors in risk modification and test sensitivity. Different testing options (e.g., restriction to the common mutations or the option of sequencing the entire CFTR gene) will also be discussed. Residual risks after a negative test must be taken into account and the cost implications discussed so that the person seeking advice can make an appropriate decision. Options of prenatal diagnostics as well as newborn screening are to be explained in detail. Another example of a frequently requested risk calculation in the situation of familial X-linked disease is shown in Figure 2.

Developmental Disabilities: Probably the most common counseling situation results from the onset of an intellectual disability and/or physical deformity of unclear etiology. In this case, an interdisciplinary clarification of the causes must first be carried out in the affected person, both from the pediatric and the medical-genetic side, in order to enable any further consultation at all on sensible therapies, prognosis and familial risks of recurrence. As genetic diagnostic capabilities increase with the development of genomic technologies, re-evaluation at intervals is useful if the diagnosis remains unclear initially. This also applies to today’s adult sufferers, whose cause clarification was often not followed up after early childhood and therefore no longer meets today’s standards. A causative chromosomal disorder, which is now diagnosed in up to 25% of patients using microarray technologies, may under certain circumstances lead to a significantly increased risk of recurrence in the family if one of the two parents is found to be a carrier due to a balanced chromosomal aberration. In practice, however, health insurers are increasingly refusing to cover the costs of indicated genetic tests. De facto, this also prevents competent counseling of the family and denies the option for prenatal diagnostics even for family members, since knowledge of the specific cause is necessary for this. Thus, increasingly, families with even putatively high risk of recurrence must bear the cost themselves or accept the risk. This is difficult to communicate given the very high standards in other medical specialties and is perceived as discriminatory.

Periconceptional and prenatal counseling situations.

Risk for carrier status of recessive diseases: A significant topic of genetic counseling is periconceptional and prenatal issues. The physicians providing care have a shared responsibility here in recognizing situations that may pose a significantly increased risk of genetic disease in offspring. In certain ethnicities, there is an increased risk of carrying recessive diseases, such as hemoglobinopathies (like sickle cell anemia or thalassemias) in areas bordering the Mediterranean Sea, Africa near the equator, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, the Caribbean, and Central and South America. After positive screening (blood count with hemoglobin electrophoresis), the causative mutation must be identified in both parents to allow prenatal testing at all, if desired. Families of Jewish descent, in keeping with their tradition, are usually themselves aware of the increased carrier probability for a certain number of metabolic diseases in their population and often actively ask about testing options. In any case, carrier testing should be discussed and offered in the context of genetic counseling. Ideally, counseling and clarification should take place before pregnancy, since during pregnancy the time factor for clarification and for subsequent decisions for or against prenatal diagnostics can be considerable. Consanguinity should also be actively inquired about as part of the family history – because in couples from countries with frequent intermarriage, the relationships are often complex and can result in a significant increase in risk, especially if a specific disease is known. However, without a concrete diagnosis, the options for genetic testing are limited. Currently, new genomic technologies, particularly high-throughput sequencing, are making it possible to study carriers for many different severe recessive diseases simultaneously. It remains questionable whether this should in principle be made possible for all patients as a preventive measure in the future. In general, health insurers are not obliged to pay for examinations carried out under the KVG.

Risk for chromosomal disorders: Whereas counseling on the general risk for chromosomal defects in pregnancy used to focus on pregnant women older than 35 years, today possible methods of risk assessment and diagnosis of common chromosomal defects need to be discussed before or at the beginning of each pregnancy. The aim of this pre- or post-conceptional genetic counseling is to discuss the informative value and limitations of various non-invasive examination procedures for risk assessment of chromosomal disorders, if the parents do not reject this procedure from the outset. The aim is to provide a basic understanding of the context and principles of testing, as well as information about possible follow-up decisions that may be required as a result of the results, to enable self-determined informed decision-making. It is not uncommon for the exclusion of a specific disease or group of diseases, such as chromosomal abnormalities, to be misinterpreted as evidence of the child’s health. Therefore, it must be mentioned that prenatal examinations can exclude an increased risk or a specifically studied disease, but cannot guarantee health. The baseline risk of serious neonatal illness is about 1-2% – and at least 3-5% if less severe, often well-treatable, impairments to child development of all causes are included.

Special consulting contents

In Switzerland, the term genetic counseling is not protected. Genetic counseling can be offered by physicians of all specialties and billed as a medical service. The consulting physician thus bears sole responsibility for his or her qualifications and the professional performance of the consultation in accordance with internationally recognized quality criteria. In principle, however, depending on the problem, the involvement of other specialized disciplines is advisable. In this respect, the GUMG regulates in particular the provision of advice before predictive and prenatal examinations, which may only be performed by an appropriately qualified physician.

Predictive diagnostics is the genetic testing to clarify the likelihood of a disease occurring only in the future. Consensus recommendations on how to proceed exist for various conditions – e.g., familial cancers or Huntington’s disease. Consultations on prenatal diagnostics include non-invasive examination procedures for general risk assessment or specification of a disease probability or diagnosis (e.g. ultrasound, first trimester risk assessment, non-invasive prenatal test on maternal blood) as well as analyses after invasive sample collection (e.g. chorionic villus sampling, amniocentesis, chorocentesis). As part of the care of the person seeking advice, professional societies recommend the collaboration of an interdisciplinary team of experts from the disciplines involved.

Perspectives

The possibilities of genomic technologies and their use in genetic diagnostics are already leading to an increasing complexity of medical-genetic patient care, including genetic counseling. In addition to the knowledge of the methodology and limitations of various examination procedures, a clinical diagnosis and evaluation with detailed findings of the phenotype nevertheless always remains indispensable in affected patients and is also a prerequisite for the appropriate use of these examination procedures as well as the interpretation of the results. Both clinically and laboratory-diagnostically, medical-genetic centers can contribute to this. For complex issues, interdisciplinary collaboration will be crucial in the future to ensure quality patient care and counseling.

Isabel Filges, MD

Further reading:

- Federal Law on Human Genetic Testing (GUMG): www.bag.admin.ch

- German Society for Human Genetics (GfH),

- Professional Association of German Human Geneticists (BVDH): S2 Guideline Human Genetic Diagnostics and Genetic Counseling. Medgen 2011; 23: 218-322.

- Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences (ed.): Genetik im medizinischen Alltag – Ein Leitfaden für die Praxis. 2nd edition, Schwabe 2011.

- Harper PS: Practical genetic counseling. 7th edition, Hodder Arnold 2010.

- Moog U, Riess O: Medical genetics for practice. Georg Thieme Verlag 2014.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(2): 26-30