Lung transplantation (Lutx) is also an established therapeutic option in childhood and adolescence when, despite exhaustion of all available therapeutic measures, a severe disease progresses, quality of life is significantly impaired as a result, and terminal organ failure appears likely in the foreseeable future. Nevertheless, lutx is a significant intervention in the physical integrity of the child with many risks.

Lung transplantation (Lutx) is also an established therapeutic option in childhood and adolescence when, despite exhaustion of all available therapeutic measures, a severe disease progresses, quality of life is significantly impaired as a result, and terminal organ failure appears likely in the foreseeable future.

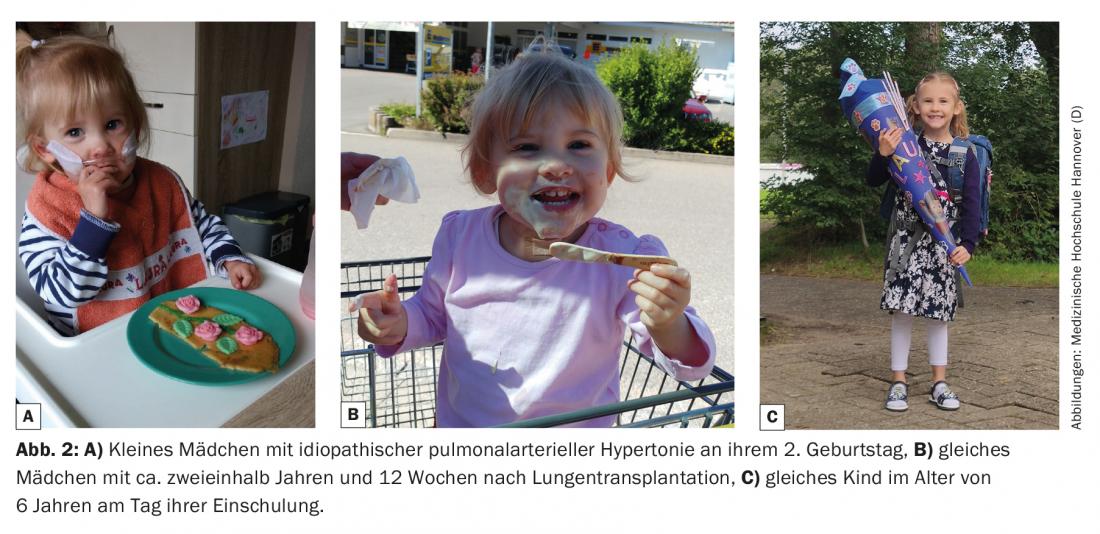

The primary goal of prolonging the lives of those affected and improving their quality of life is achieved in most cases [1,2] (Figs. 1 and 2). Nevertheless, lutx represents a significant intrusion into the physical integrity of the child with many risks, potentially serious complications, and the need for lifelong drug therapy with multiple potential side effects. This in turn has significant social and psychological effects on the growing child or adolescent, but also on the family environment. The type and extent are variable and depend on many factors such as the underlying disease, additional comorbidities, age, social environment, and the psychological stability of the affected person. For this reason, in my view, a lutx represents a possible treatment option but not a mandatory therapeutic conclusion in children with life-threatening disease. A conscious decision not to have a transplant does not mean giving up on the child, nor is it a sign of weakness or lack of care, but may even be a better decision for some, and may save them from unnecessary suffering.

In order to be able to make this serious decision, for or against transplantation, a detailed and honest explanation of the patient as well as the legal guardians is indispensable, taking into account the individual medical and social circumstances. In particular, it is important not only to accept the child’s wishes (which do not always correspond to those of the parents), provided the child is of an age capable of making decisions, but also to actively support them.

It is difficult for me to write about growing up after lung transplantation in childhood and adolescence in general. For this reason, I have decided to first provide an overview of important medical aspects of lutx in childhood and adolescence, and then to address selected special features and challenges depending on the stage of life.

Lung transplantation in children and adolescents

Lung transplants are performed annually in 120-140 children in approximately 40 centers worldwide. Most centers perform fewer than 5 transplants per year, and fewer than 5 centers report 10 or more transplants per year to the International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) [3]. The number of combined heart-lung transplants has steadily decreased over the past 20 years and is now indicated only in exceptional cases. The average age at the time of transplantation is between 12-15 years and cystic fibrosis (CF) is still the most common indication at about 60%, followed by pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) [4]. However, the proportion of pediatric CF patients with terminal lung disease is expected to decrease steadily in the coming years due to earlier detection and specific therapy through universal newborn screening and the availability of highly efficient CF modulators. On the other hand, the number of younger children with severe diffuse lung disease, such as surfactant dysfunction, is likely to increase, particularly because of increasingly improved intensive care treatment options.

Determining when to list depends very much on the severity and progression of the underlying disease. Important listing decision criteria in patients with CF include FEV1 below <30% of target, rapid unstoppable decline in pulmonary function, repeated life-threatening exacerbations of infection, recurrent severe hemoptysis, or chronic pulmonary hypercapnic insufficiency [5,6]. For other conditions, validated decision criteria are lacking for children, and especially in patients with hereditary or idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), prognosis assessment is very difficult due to increasingly better treatment options. Often, patients present to a transplant center too late, so that adequate evaluation and education is no longer possible, or patients cannot be listed at all due to their critical condition (e.g., ventilated and/or on ECMO). Therefore, any patient with severe, chronic, and progressive lung disease should be evaluated early in a center [5]. A long waiting period must also be considered when deciding to list. The average wait time for pediatric patients in Hanover is about 3.5 months. Transplant procedures vary depending on the center. In Hannover, Germany, sequential bilateral double lung transplantation using a minimally invasive technique via anterolateral thoracotomy, without extracorporeal lung replacement procedures such as ECMO or heart-lung machine, if possible, is favored. Patients with PAH are an exception to this rule. Here, intraoperative relief of the right ventricle is always performed by veno-arterial ECMO or (e.g., in infants) with a heart-lung machine. Because muscular left ventricular hypotrophy develops in all patients with severe PAH, left ventricular decompensation due to volume loading with corresponding pulmonary venous backpressure and resulting pulmonary edema is very common after transplantation. This in turn is associated with a long ventilation time and many complications such as barotrauma, long-term sedation, immobilization, and infections [7]. For this reason, combined heart-lung transplantation continues to be favored at some centers for patients with severe PAH. In Hannover, only isolated lung transplantations are performed in this patient group. After successful transplantation, however, va-ECMO is always left in place to unload the left ventricle to prevent volume loading. Patients can usually be extubated with this procedure after a short time and the left ventricle can be “trained” over the following days by progressively reducing ECMO flow under echocardiographic control and measurement of left atrial pressure until ECMO can then be explanted after an average of 7 days. At our center, this procedure has resulted in a significant reduction in ventilation times, a reduction in primary graft dysfunction, and a significant reduction in mortality [1,8]. Although a survival benefit from induction therapy, e.g. with polyclonal antithymocyte globulin or monoclonal IL-2 receptor antagonists, has not yet been demonstrated in randomized controlled trials, it is now performed in most centers [3].

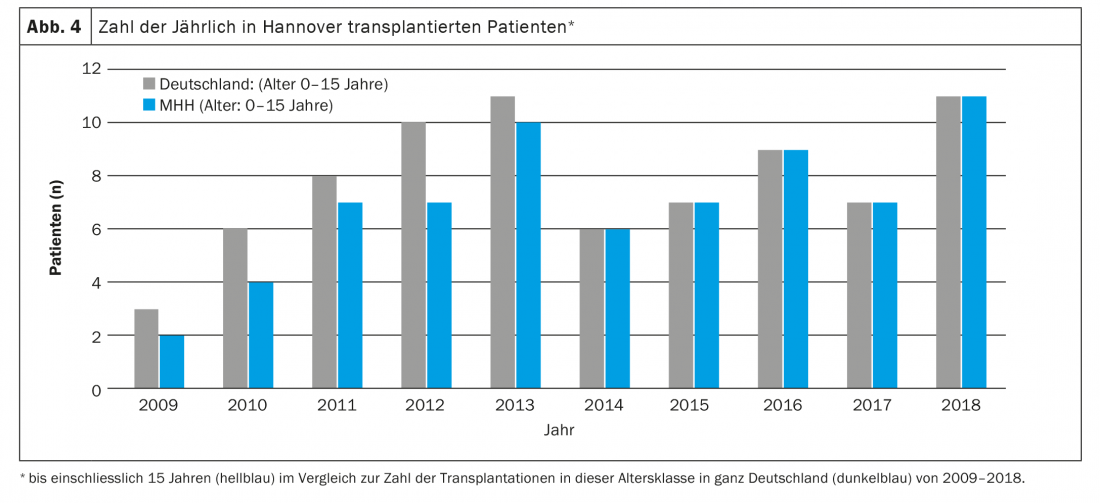

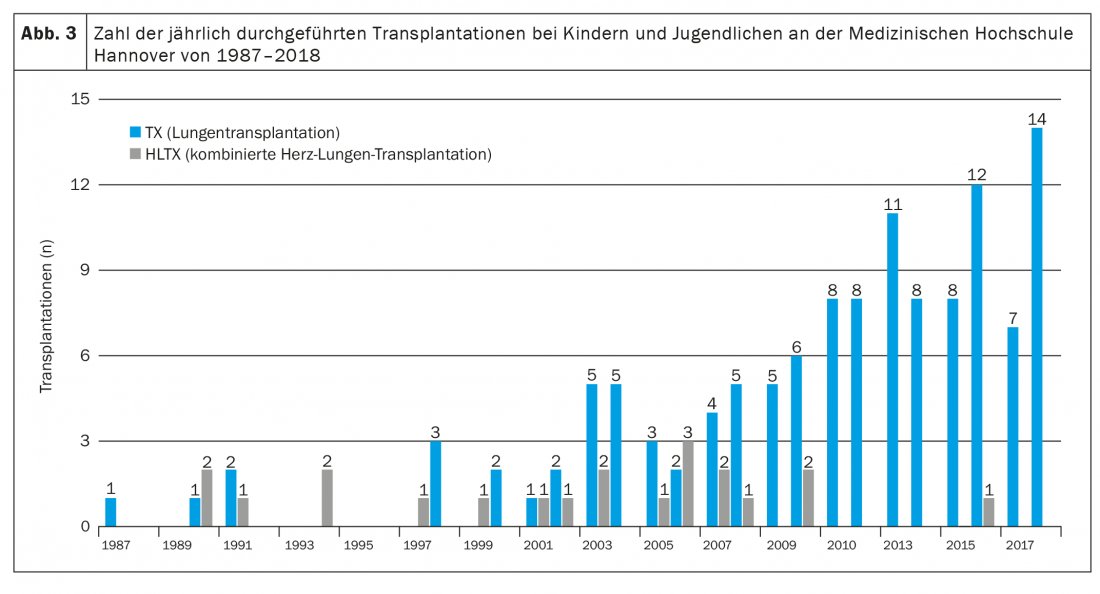

Long-term immunosuppressive therapy consists of a calcineurin inhibitor, a cell cycle inhibitor, and a glucocorticosteroid, usually in the form of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisolone [3,4,9]. In addition, all patients (in Hannover) receive ganciclovir or valganciclovir for prevention of CMV infection, itraconazole or voriconazole for prevention of fungal infection, and cotrimoxazole for prophylaxis of Pneumocystis jiroveccii infection, at least in the first months after transplantation. In addition, side effects due to immunosuppressive therapy, such as arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus (especially in CF patients), and renal insufficiency, often occur very early and need to be treated with drugs [4]. Due to the intensive immunosuppression required in the first 12 months after transplantation, infections represent the most common cause of death in the first postoperative year [9]. Serious long-term consequences (within the first 5 years after Lutx) of immunosuppressive therapy include, in particular, severe renal failure (in about 6%), diabetes mellitus (in about 30%), and malignancies (in about 10%) [3,4,9]. While skin tumors are the most common malignancy entity in adults, pediatric patients predominantly develop EBV-associated lymphomas. The most common cause of death beyond the first year after transplantation, even in children, is chronic allograft dysfunction, usually in the form of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) [10]. 5 years after transplantation, about 50% of patients are affected [4]. Compared with other solid organ transplants, patients after Lutx continue to have the poorest prognosis. The median survival after Lutx of all pediatric patients reported in the ISHLT registry from 1992-2017 was 5.7 years and has increased to 6.4 years in more recent years (2002-2009) [4]. This is largely due to improved perioperative treatment options with a reduction in early mortality. However, prognosis varies, sometimes considerably, between different centers and seems to depend in particular on the size and thus the experience of a transplant program [11]. With 8-14 transplantations per year, the Children’s Hospital of Hannover Medical School is one of the largest pediatric lung transplantation centers worldwide (Fig. 3) . Here, 5-year survival has increased in recent years, with increasing annual patient numbers, from 41% (transplant period 1987-2008) to over 80% (transplant period 2014-2018) [1,12].

A major reason for the poor prognosis compared to other solid organ transplants is probably the significantly higher exposure of the lung to the environment with a resulting constant stimulation of the immune system. For example, acute or chronic lower respiratory tract infections are a risk factor for chronic graft rejection after lung transplantation.

The above facts make clear the complexity, difficulties, and extraordinary stresses of a lutx for children, adolescents, and their families, and suggest the impact it has on the life of a growing child.

Specific aspects in infants and young children

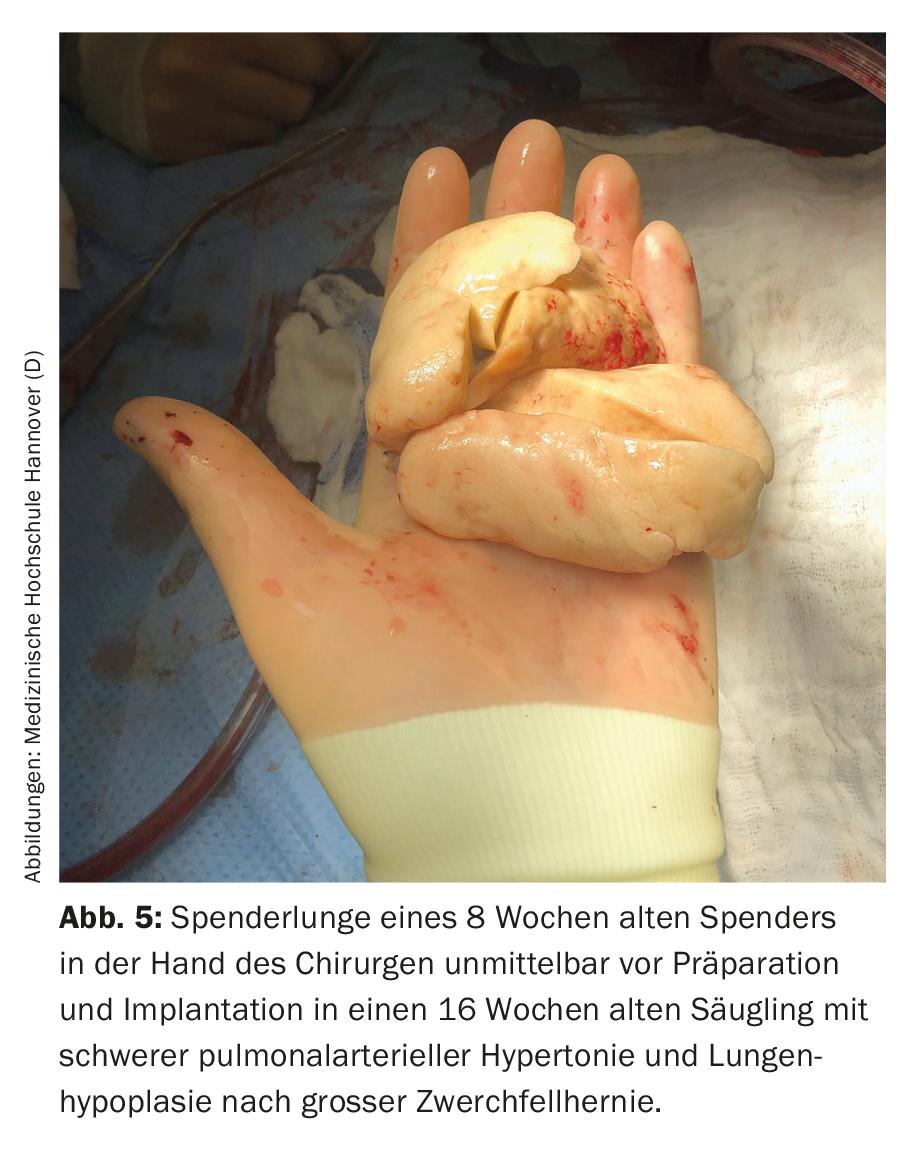

The main indications for lung transplantation in this age group are diffuse parenchymal lung disease and PAH. Parents and medical staff are faced with major challenges even before transplantation. In most cases, the children are in an acutely life-threatening condition, often require ventilation, are not infrequently completely immobilized, and must expect long (inpatient) waiting times due to the scarcity of available organs. In addition to the psychological strain on parents, the long waiting time is also associated with glaring organizational problems and is very stressful for any healthy siblings that may be present. Often one parent, in most cases the mother, cannot be at home for weeks or months, because one person has to take care of the sick child in the clinic, which is almost never located in the family’s hometown. In Germany, for example, almost all children under 16 years of age have been transplanted at Hannover Medical School in recent years, and only a few of them live in Lower Saxony or even in Hannover (Fig. 4) . The resulting consequences are probably hardly imaginable for us as medical personnel. Due to the poor condition before transplantation, lack of physical reserves, young age and associated difficult surgical (Fig. 5) and intensive care procedures, the risk of preoperative and postoperative complications is high. Because of their age, children often cannot articulate their wishes and fears, even if they are conscious. Parents are torn between fear for their child’s life and concern that the transplant will not even be achieved or that the child will die after the transplant and endure a severe ordeal until then. Due to the small total number of transplanted patients at this age, concrete, reliable information on prognosis is not possible. Dealing with the children and their parents, as well as conducting conversations, therefore requires a high degree of empathy, honesty, knowledge of human nature, and especially time.

We physicians are not prepared for such scenarios during our studies and are therefore imperatively dependent on the support of psychologists, psychotherapists and nursing staff, among others. Another problem is the constantly decreasing time resources due to the increasing pecuniary pressure to perform, the glaring shortage of personnel and the continuously increasing bureaucratic tasks of the medical staff. In addition, at least in Germany, more and more non-physician positions are being eliminated. Professions that simply do not “pay off” in the performance-oriented hospital society, such as art therapists, music therapists, psychotherapists, physiotherapists or clinic clowns, are in many ways much more important for the children and their parents than doctors and contribute significantly to the well-being of the patients and thus to the success of a transplant. Here, a rethink on the part of the institutions would not only be desirable, but in my view also imperative. Unfortunately, the efficiency of the work of the above-mentioned professional groups can hardly be proven on the basis of controlled studies. Thus, calculating staffing requirements based on robust data is a major problem of “evidence-based medicine” and does not make sense in such marginal areas as pediatric transplant medicine. Often, parents find conversations with other families whose child was transplanted at a similar age with the same or similar indication very helpful. Therefore, in the decision-making process, we always offer referrals to such families. However, the post-transplant period also presents a particular challenge in this age group. On the one hand, due to the narrow therapeutic range as well as the manifold side effects of the immunosuppressants, close-meshed blood tests are required, which are stressful for the child. Initially daily, then weekly and later at 4-weekly intervals. The most important examination for early detection of organ dysfunction is lung function measured daily (at home). However, this is not yet possible with infants and toddlers. Other monitoring tests such as respiratory rate and oxygen saturation are the only (poor) alternatives here. Due to the high risk of infection, the children are not allowed to attend kindergarten. This in turn has significant psychosocial consequences for the child and places a burden on the family, especially if the child is being raised by a single parent.

Often, full vaccine protection does not exist at the time of transplantation and the vaccine response under immunosuppression is significantly limited. Furthermore, live vaccines are contraindicated in children after Lutx. This in turn increases the risk of infection and requires special preventive measures. What we are suffering restrictions in the context of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has always been and still is lived normality, especially for young children after Lutx. Often, due to the above-mentioned circumstances, the families get into financial difficulties and therefore need additional support. Fortunately, we were able to show that the survival of transplanted infants in our center is nevertheless not worse compared to adolescents, but tends to be even better [1]. In addition to a possible higher plasticity of the immune system with an associated lower rate of acute and chronic rejections (despite lower immunosuppression), this is in my opinion mainly explained by a significantly better therapy adherence (the parents still administer the drugs themselves at this age) compared to adolescents. However, the encouragingly good prognosis with a 5-year percentage survival of more than 80% [1] also brings new challenges and obligations, namely to prevent iatrogenic long-term damage whenever possible. Therefore, the necessity of every single medication, every invasive examination and every imaging diagnosis with radiation exposure or required sedation/anesthesia should always be critically questioned. Furthermore, controlled studies on the efficacy and safety of the drugs used in lung transplanted children would be extremely important, but are unfortunately not available due to small patient numbers as well as lack of interest from the pharmaceutical industry and lack of public funding.

Specific aspects for preschool and school children

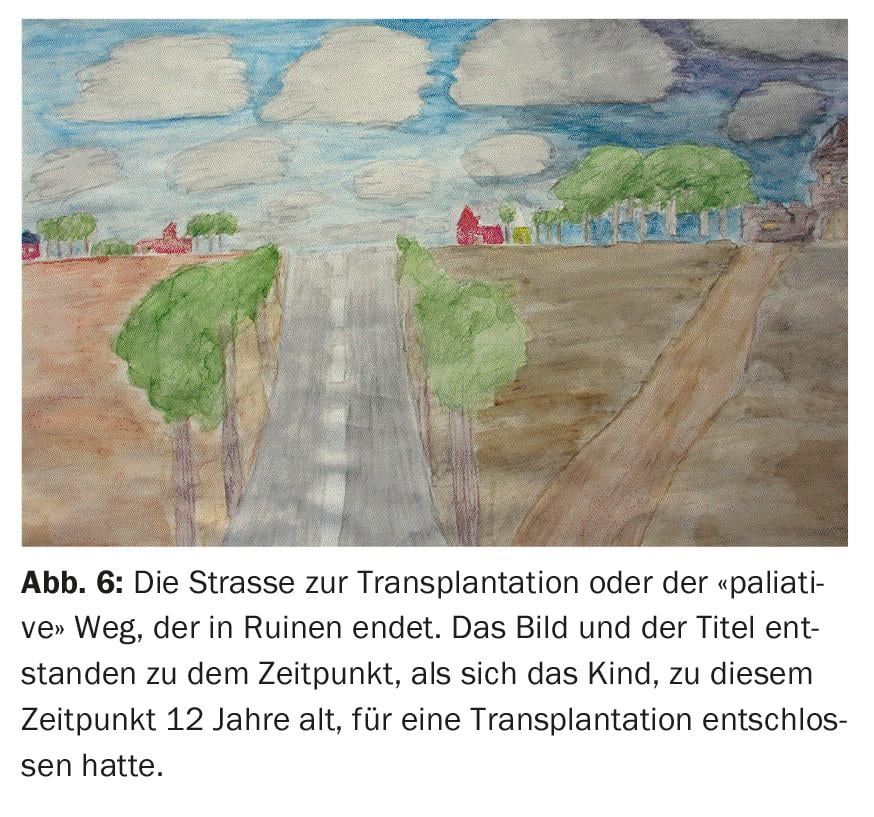

Much of what was mentioned earlier about infants and toddlers also applies to preschoolers and school-age children and therefore will not be explained again. However, CF is the most common indication in this age group. Unlike infants and toddlers, older children are rarely in an acutely life-threatening condition at the time of listing, which allows more time for discussion and adequate evaluation. In addition, children can almost always wait at home for a donor organ if they are listed. However, it is important at this age to actively involve the children in the educational discussions, to address their questions sufficiently and understandably and, in particular, to take their wishes and fears very seriously. From my own experience I know that even younger children can cope much better with complications and unpleasant examinations or treatments after lung transplantation if they have been adequately prepared for them before transplantation. Very often in the course of educational talks I have the feeling that the children cannot or do not want to verbalize their fears and worries and that they, like the adolescents, want to be “strong” for their parents. This makes accompanying psychological support and art therapy all the more important for these children, in addition to the educational sessions. With colors, shapes and pictures, they often express thoughts, fears, expectations and hopes much better than they could in words (Fig. 6) . Furthermore, painting therapy quite obviously has a relevant therapeutic effect. As a rule, children are allowed to attend school 6 months after transplantation, and apart from regular medication and follow-up checks, there are hardly any other restrictions on their daily lives.

Specific aspects in adolescents

Adolescent patients are already well able to understand the importance of lung transplantation, with all the potential advantages and disadvantages, and should therefore be the primary interlocutors during educational discussions. Your decision, whether for or against transplantation, is primarily authoritative and must therefore be accepted. Often, the adolescents already have a long path of suffering behind them and were not able to experience the carefree childhood as their healthy peers. For this reason, their expectations for lung transplantation are very high. However, these often cannot be fulfilled in their entirety. Here, it is therefore important to convey that although transplantation represents a real chance for a longer and better life, one is not healthy afterwards and that regular intake of medication, daily check-ups and avoidance of potentially harmful behaviors such as excessive alcohol consumption or smoking are extremely important and therefore a basic requirement for inclusion on the waiting list. Girls must be educated that they should not have children later due to the potentially severe teratogenic side effects of immunosuppressants and ensure detailed gynecologic counseling on contraception.

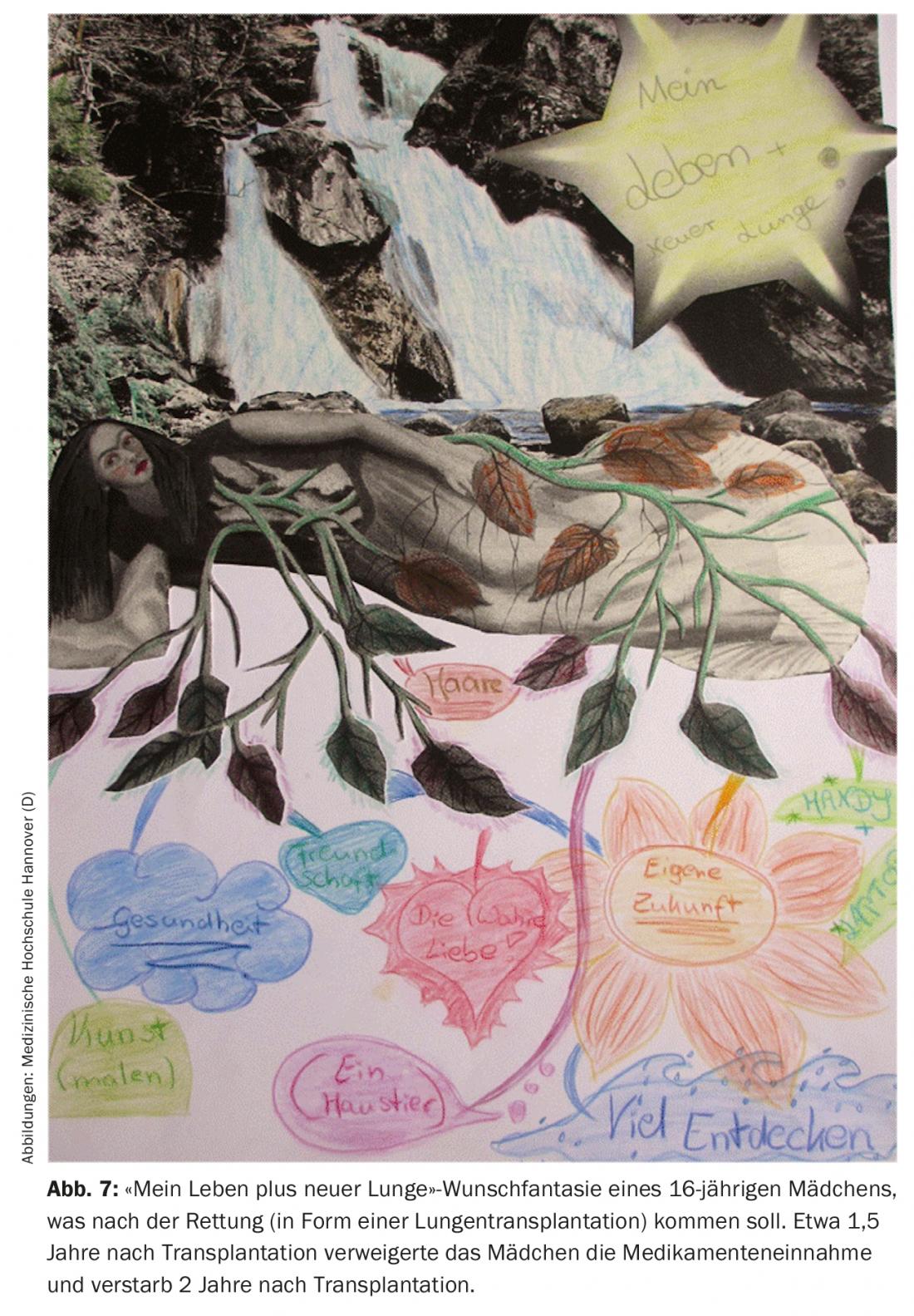

My perception is that the care of adolescents after lung transplantation is often much more difficult than for younger children. The main problem, and in my view the most common cause of death in this age group, is lack of adherence to therapy. Sometimes adolescents invest more time in “covering up” treatment measures and/or check-ups that have not been carried out than in carrying them out consistently. Intuitively, this regularly triggers anger and frustration in me (Fig. 7) . But these reactions do not help the people concerned and make things inadequately easy for themselves by transferring responsibility. Each of us who has children of this age knows how difficult, but also important, the phase of adolescence is. It is characterized by identification conflicts, the desire for autonomy and self-determination, and the inner rejection of advice or orders from adults. Prohibitions, threats, and commandments tend to incite people to do the opposite. At least that was the case for me during this time. In addition, there is also the social pressure of the peer group and the desire to “belong,” even when it comes to testing boundaries and forbidden things. How young people cope with this, of course, also depends to a large extent on the support and intactness of their social environment. It is therefore our task to communicate these topics well in the course of education, to build up a relationship of trust and, with the help of parents, psychologists and social workers, to identify points of conflict as early as possible and to find individualized solutions at eye level with the adolescent patients.

Lastly, I would like to address the important issue of transition. Adolescents should be intensively prepared for the time as an “adult” patient from the age of 16 at the latest. In my opinion, the well-intentioned leadership care and decrease in tasks and responsibilities are mistakes that we pediatricians still make too often, especially with chronically ill patients. We must be aware that we are not promoting the independence of the patient. For this reason, a structured transition program is important for long-term outcomes beyond age 18.

Summary

Lung transplantation offers children and adolescents, regardless of age, the chance for a longer and better life. However, it is also associated with complications and lifelong commitments that are very different from a normal life and demand a lot from patients as well as their families. Therefore, detailed evaluation, thorough education, resulting selective identification of suitable candidates, and multidisciplinary care before and after transplantation are always essential. The individualized patient care required for this is time-consuming and personnel-intensive. This is not adequately addressed in the current healthcare system. In order to improve the long-term survival as well as the quality of life of the children entrusted to us, we should not tire of fighting against it.

Take-Home Messages

- The average age at the time of transplantation is between 12-15 years, and cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most common indication at approximately 60%, followed by pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH).

- Each phase of life before and after lung transplantation presents unique medical and psychosocial challenges that may vary interindividually but are essential to consider.

- Close, individualized psychosocial care for transplanted children and their families is extremely important.

- Lack of treatment adherence in adolescents after lung transplantation is a major risk factor for chronic organ rejection.

- Serious long-term consequences of immunosuppressive therapy include, in particular, severe renal insufficiency (approx. 6%), diabetes mellitus (approx. 30%), and malignancies (approx. 10%). Pediatric patients predominantly develop EBV-associated lymphomas.

- A major reason for the poor prognosis compared to other solid organ transplants is probably the significantly higher exposure of the lung to the environment with a resulting constant stimulation of the immune system.

Literature:

- Iablonskii P, Carlens J, Mueller C, et al: Indications and outcome after lung transplantation in children under 12 years of age: A 16-year single center experience. J Heart Lung Transplant 2021 Oct 28.

- Schmid FA, Inci I, Burgi U, et al: Favorable outcome of children and adolescents undergoing lung transplantation at a European adult center in the new era. Pediatr Pulmonol 2016; 5(11): 1222-1228.

- Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC, et al: The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-sixth adult heart transplantation report – 2019; focus theme: donor and recipient size match. J Heart Lung Transplant 2019; 38(10): 1056-1066.

- Hayes D Jr AD, The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation – International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry, Dallas,Texas, Harhay MO, et al: The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Twenty-fourth pediatric lung transplantation report – 2021; Focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant 2021; 40(10): 1023-1034.

- Leard LE, Holm AM, Valapour M, et al: Consensus document for the selection of lung transplant candidates: An update from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2021; 40(11): 1349-1379.

- Solomon M, Mallory GB.: Lung transplant referrals for individuals with cystic fibrosis: A pediatric perspective on the cystic fibrosis foundation consensus guidelines. Pediatr Pulmonol 2021; 56(2): 465-471.

- Huddleston CB: Lung transplantation for pulmonary hypertension in children. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2010; 11(2 Suppl): S53-S56.

- Tudorache I, Sommer W, Kuhn C, et al: Lung transplantation for severe pulmonary hypertension – awake extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for postoperative left ventricular remodeling. Transplantation 2015; 99(2): 451-458.

- Goldfarb SB, Hayes DJ, Levvey BJ, et al: The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Twenty-first Pediatric Lung and HeartLung Transplantation Report-2018; Focus Theme: Multiorgan Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2018; 37(10): 1196-1206.

- Verleden GM, Raghu G, Meyer KC, et al: A new classification system for chronic lung allograft dysfunction. J Heart Lung Transplant 2014; 33(2): 127-133.

- Khan MS, Zhang W, Taylor RA, et al: Survival in pediatric lung transplantation: the effect of center volume and expertise. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015; 34(8): 1073-1081.

- Gorler H, Struber M, Ballmann M, et al: Lung and heart-lung transplantation in children and adolescents: a long-term single-center experience. J Heart Lung Transplant 2009; 28(3): 243-248.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(5): 12-18