At the three-country meeting in Bern on the topic of heart failure, experts spoke about the implementation of the guidelines in practice and went into more detail about the possibilities of telemonitoring. In addition, the specific clinical benefit of biomarker diagnosis was up for discussion. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is a particular challenge, but it is worthwhile to take another close look at the (so far rather disappointing) study situation.

(ag) Prof. Dr. med. Frank Ruschitzka, University Hospital Zurich, spoke about the implementation of the ESC guidelines in outpatient practice: What would be desirable and where do we stand? The publication of the PARADIGM-HF trial raises hope for a new era in the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFREF). Looking back, as an article in the New England Journal of Medicine does [1], it is clear that research over the past three decades has been very productive overall, with steady progress being made: Whereas at the beginning of the period under review (1986-2014) only digoxin and diuretics were available in the first-line setting (without mortality benefit), there is now strong evidence regarding mortality reduction for ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, cardiac devices, aldosterone antagonists, and, more recently, for the so-called ARNIs (angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors). “So we can be proud of what we have already achieved and hope that the development will continue like this,” the speaker explained. “However, it always takes a while until the current state of research or the guidelines have completely arrived in practice: One assumes a delay of about 15 years – only then are innovations deeply rooted in everyday clinical practice. This fact is independent of the attention the respective guidelines receive: Heart failure guidelines are by far the most read and clicked on the ESC website.”

Better than expected?

However, if one looks at data from the registries, one sees that implementation is definitely progressing and is working better in Europe than one might think: A long-term registry with 12 440 patients from 21 ESC countries has been published in this regard by Maggioni et al. [2] evaluated. The authors conclude that the treatment of chronic heart failure in particular is mostly adherent to the guidelines (including reasons for non-adherence):

- 3.2% of patients with reduced ejection fraction do not receive ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, although they would be indicated.

- 2.3% do not receive beta-blockers, although they would be indicated.

- 5.4% do not receive aldosterone antagonists, although they would be indicated.

Approximately one-third of all patients receive the medication at the target dose; for the remaining two-thirds, there are documented reasons why this is not the case (ongoing titration was cited as the primary reason).

“According to the paper, there is a relevant underrepresentation in the area of devices: Almost half of the patients who should receive a device (“implantable cardioverter-defibrillator” ICD, “cardiac resynchronization therapy” CRT) do not receive it. The most important reasons are considered to be the uncertainty of the physician regarding the indication, the patient’s refusal, or logistics/costs,” Prof. Ruschitzka explained. “In the USA, a patient could sue for such a circumstance. It is important to remember that not only the drugs but also the implantation devices have IA evidence. Fonarow et al [3] conclude that the correct implementation of evidence-based knowledge in practice could prevent almost 68,000 deaths per year (20,000 of which are due to the indicated use of devices). Of course, costs play a crucial role: If we were to provide all patients with devices that have such an indication, our health insurers would soon be bankrupt.”

Long-term care in practice

Important key points to an even better implementation are functioning multidisciplinary approaches (involvement of nursing staff) and specific training programs for heart failure, which could compensate for the lack of specialists in this field. Prof. Dr. med. Stefan Störk, Würzburg, therefore also emphasized the great importance of further training as a heart failure nurse. This job description is very heterogeneous, depending on the required range of services in the respective setting. Essential components are patient education and counseling. The syndromal nature of heart failure requires caregivers who are “multimorbidly trained,” according to the speaker. A structured care strategy for heart failure is a prerequisite for successful multidimensional long-term therapy: The HeartNetCare-HF™ Würzburg treatment program includes, for example, nurse-based telephone monitoring, telephone-based patient education and a standardized documentation concept.

But what is the evidence for telemonitoring in heart failure patients? This question was addressed by Prof. Dr. med. Friedrich Köhler, Berlin: “Telemonitoring only works as part of the so-called Remote Patient Management (RPM) – consisting of a guideline-based therapy, training/self-empowerment and telemonitoring (invasive with implants or non-invasive). It took a while before randomized controlled trials were finally done on the procedure.” Key examples include:

IN-TIME [4]: Is the latest study. It also demonstrated for the first time a reduction in mortality with telemonitoring.

CHAMPION [5]: Showed a 30% reduction in hospitalization rate in the monitoring group.

TIM-HF [6]: No effect was found in the primary endpoint (all-cause mortality) despite great effort (comparison of telemonitoring group vs. group under standard care). However, there was an improvement in quality of life.

In particular, the subgroup of patients hospitalized for heart failure seems to benefit from telemedicine (was evident in a prespecified subgroup analysis of TIM-HF, among others [7]).

“Thus, the study situation, although promising, is not yet sufficient for inclusion in the guidelines. We are therefore currently undertaking further studies (e.g. TIM-HF II). At this time, it is clear that patients with systolic chronic heart failure (NYHA II and III) benefit from telemonitoring up to twelve months after hospitalization. This should be followed by a lifetime of self-empowerment,” the expert said.

Importance of biomarkers

BNP and NT-proBNP are the best biomarkers for the diagnosis of heart failure according to numerous studies in different settings. However, according to Prof. Hans-Peter Brunner-La Rocca, MD, Maastrich, the actual effect of BNP testing on clinical outcome (i.e., the concrete benefit) has been studied prospectively rather rarely and remains largely unclear: A meta-analysis [8] compared routine care for acute dyspnea with diagnostic BNP testing. It concludes that the test (performed in the emergency department) slightly reduced the length of hospitalization by 1.22 days and decreased the admission rate by 18% (not significant). Mortality was not affected by the test.

An interesting new example of a cardiac biomarker is the so-called “long non-coding RNAs” (LIPCAR): LIPCAR allows identification of patients with cardiac remodeling and is independently associated with future cardiovascular death in heart failure from other risk markers [9].

Lessons from negative studies

“In the last ten years, we have mainly taken care of HFREF, and here we have conducted studies with positive results and celebrated ourselves,” said PD Dirk Westermann, MD, Hamburg, Germany. “But what have we learned in the same time for patients with HFPEF (with preserved ejection fraction)? As it seems, hardly anything. To date, no treatment has been able to show a convincing reduction in mortality or morbidity (which is also reflected in the guidelines). However, it is critical to look very closely at the studies in this area (such as PEP-CHF, Charm-Preserved, I-Preserve, TOPCAT) and not be put off by the negative or neutral results.”

PEP-CHF [10] showed complete convergence of the curves (placebo and perindopril) in the composite primary endpoint (all-cause mortality and hospitalization) in the long term, so it is a neutral study. The study had insufficient statistical power for its primary endpoint, and many patients discontinued verum and placebo therapy after one year and switched to ACE inhibitors. This may have influenced the results.

Charm-Preserved [11], however, narrowly missed significance in the primary endpoint (cardiovascular death or hospitalization) (candesartan and placebo were compared): p=0.051. On closer inspection, this result was exclusively due to significantly lower hospitalization rates (p=0.047).

I-Preserve [12] again showed no difference at all in the administration of irbesartan or placebo (primary end point was composite of all-cause mortality and hospitalization).

TOPCAT [13] also failed the primary endpoint of cardiovascular death, cardiac arrest, or hospitalization (spironolactone vs. placebo) but, like Charm-Preserved, had a significantly lower hospitalization rate (p=0.04). Outcomes also appear to be dependent on patient origin (non-prespecified outcome for US collective showed significant improvement in hospitalization and mortality).

HFPEF – a difficult case

“The question is why we trivialize the evidence to date. In other areas, a significant reduction in hospitalization rates would be enough for inclusion in guidelines. The problem seems to me that we don’t really know what we want to achieve with therapy in HFPEF,” he said. “Which patients do we actually want to treat: HFPEF with or without diastolic dysfunction? Charm-Preserved and I-Preserve, for example, involved quite different numbers of patients with diastolic dysfunction (67 vs. 53%). And is the BNP cutoff alone sufficient? A valid question is also whether co-medication may be a problem. Last, it is hoped that in the future there will be more specific approaches (under the buzzword “personalized medicine”) that will be more targeted.”

From today’s perspective, it is at least doubtful that the ARNIs celebrated in HFREF will also lead to resounding success in HFPEF. It remains to be seen (so far there is the PARAMOUNT study on this).

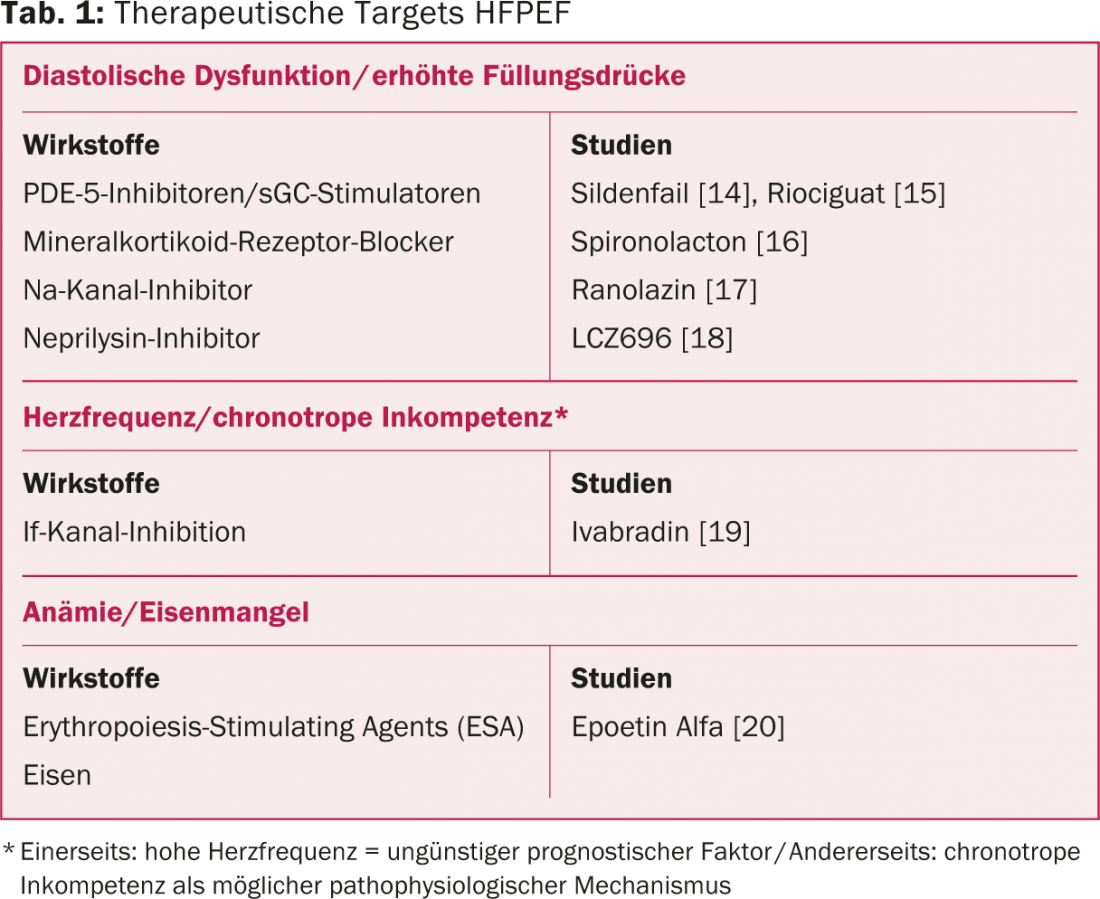

According to PD Dr. med. Micha Maeder, St Gallen, possible future therapeutic targets are diastolic dysfunction/myocardial fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension, heart rate/chronotropic incompetence, and anemia/iron deficiency. Table 1 provides an overview of the study situation.

Source: Heart Failure, Trilateral Meeting, October 2-4, 2014, Bern, Switzerland.

Literature:

- Sacks CA, et al: N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 989-91.

- Maggioni AP, et al: Eur J Heart Fail 2013; 15(10):1173-1184.

- Fonarow GC, et al: Am Heart J 2011 Jun; 161(6): 1024-1030.e3.

- Hindricks G, et al: Lancet 2014 Aug 16; 384(9943): 583-590.

- Abraham WT, et al: Lancet 2011 Feb 19; 377(9766): 658-666.

- Koehler F, et al: Circulation 2011 May 3; 123(17): 1873-1880.

- Koehler F, et al: Int J Cardiol 2012 Nov 29; 161(3): 143-150.

- Lam LL, et al: Ann Intern Med 2010 Dec 7; 153(11): 728-735.

- Kumarswamy R, et al: Circ Res 2014 May 9; 114(10): 1569-1575.

- Cleland JGF, et al: Eur Heart J 2006; 27(19): 2338-2345.

- Yusuf S, et al: Lancet 2003 Sep 6; 362(9386): 777-781.

- Massie BM, et al: N Engl J Med 2008 Dec 4; 359(23): 2456-2467.

- Pitt B, et al: N Engl J Med 2014 Apr 10; 370(15):1383-1392.

- Guazzi M, et al: Circulation 2011 Jul 12; 124(2):164-174.

- Bonderman D, et al: Circulation 2013 Jul 30; 128(5): 502-511.

- Edelmann F, et al: JAMA 2013 Feb 27; 309(8): 781-791.

- Maier LS, et al: JACC Heart Fail 2013 Apr; 1(2): 115-122.

- Solomon SD, et al: Lancet 2012 Oct 20; 380(9851): 1387-1395.

- Kosmala W, et al: J Am Coll Cardiol 2013 Oct 8; 62(15): 1330-1338.

- Maurer MS, et al: Circ Heart Fail 2013 Mar; 6(2): 254-263.

CARDIOVASC 2014; 13(6): 34-37