The consumption of omega-3 fatty acids is associated with positive effects on the cardiovascular system. Direct mechanisms such as reduction of blood pressure, improvement of ejection fraction, platelet aggregation inhibition or antiarrhythmic effects were indeed found in experimental studies. Association studies have also shown that consumption of omega-3 fatty acids in the context of fish consumption (especially cooked, but not fried fish) is associated with reduced cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. However, the majority of intervention studies conducted in recent years have produced sobering results with regard to the effect of omega-3 fatty acids on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality – no clear positive effects could be shown here.

The 73-year-old patient H.M. appears slightly upset in your consultation with a can of “fish oil capsules”. His sister gave them to him, saying that these were good for the heart and circulation. H.M. now thinks that with his high blood pressure and elevated cholesterol levels and additional family risk with a father who had already suffered a heart attack at the age of 48, the fish oil capsules would certainly be beneficial and does not understand why you, as a doctor, have not yet made him aware of the protective effects of these capsules. Did you actually withhold anything from H.M.? Are fish oil capsules an option in the treatment of patients with increased cardiovascular risk?

Omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids

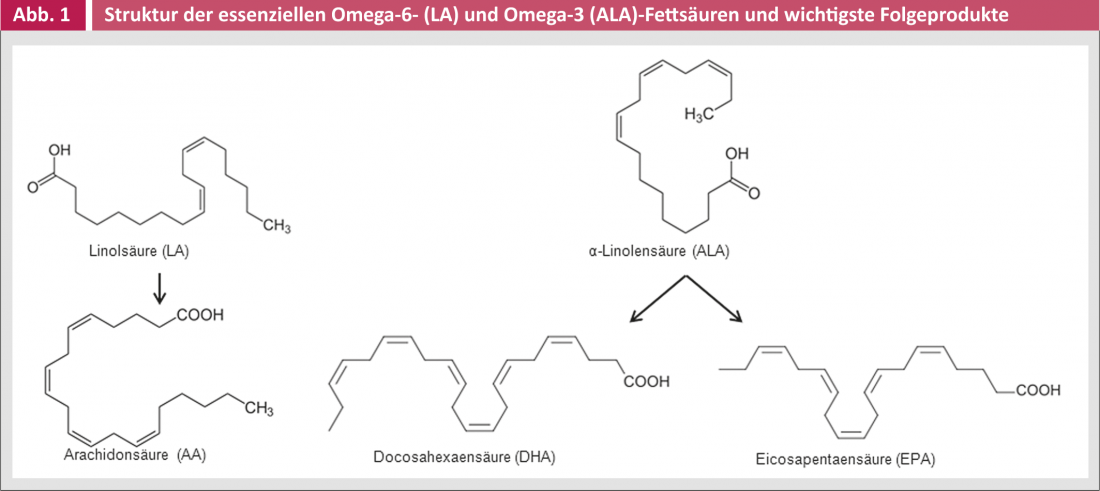

Omega-6 and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, by definition, have a first double bond 6 and 3 C atoms away from their methyl end, respectively. Linoleic acid (LA, omega-6) and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA, omega-3) are essential fatty acids from which fatty acids such as arachidonic acid (AA, omega-6), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, omega-3) (Fig. 1) are formed. The ratio of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids present in the body is essentially determined by the consumption of the two essential fatty acids as well as EPA and DHA. While fish oil consists of about 30% EPA and DHA (in about equal parts), algae oil consists practically exclusively of DHA, while for example krill oil contains a majority of EPA. Poultry meat – apart from cold water fish – has the highest EPA and DHA content. Flax, canola or soybean oil are important sources of ALA.

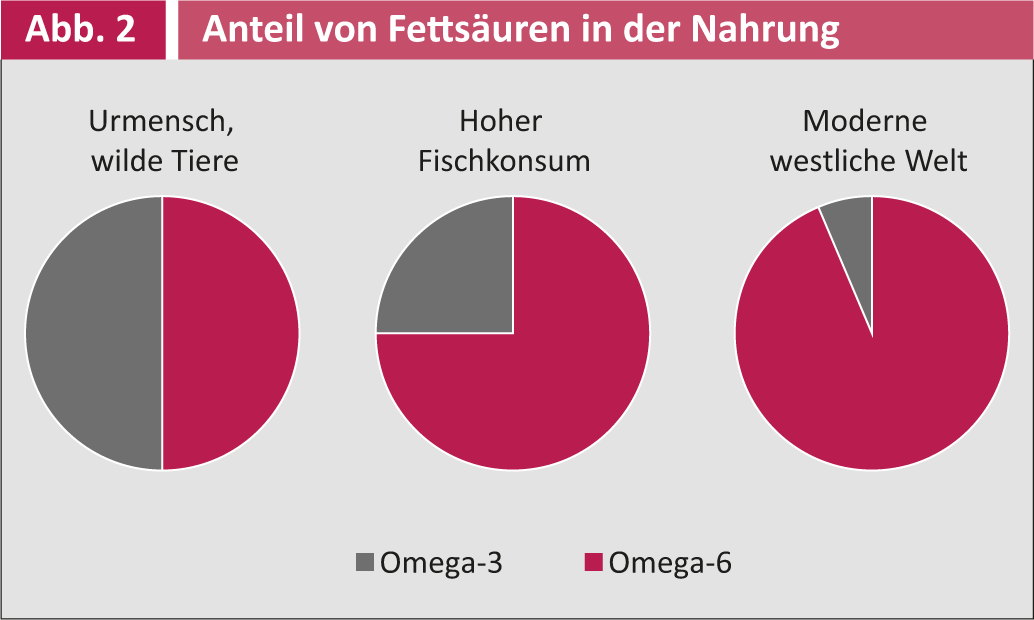

Of interest is the significant reduction in the intake of omega-3 fatty acids during the development of civilization. Prehistoric humans are thought to have had a ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids in their diet of about 1:1, similar to what is still observed in wild animals today. In modern humans, however, this ratio is about 15:1. The exceptions are cultures and countries, such as Japan, with significantly higher consumption of fish. In Japan, the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acid consumption is approximately 4:1 (Fig. 2) [1].

Possible mechanisms of action of omega-3 fatty acids.

Over the past decades, a number of mechanisms have been described that mediate any beneficial effects of omega-3 fatty acids on the cardiovascular system. These include metabolic effects such as lowering triglycerides and decreasing triglyceride accumulation in the liver. Of particular interest is a potential reduction in inflammatory tissue responses or insulin resistance. More direct positive effects on the cardiovascular system have been found in various experimental and clinical studies to be a reduction in blood pressure, improvement in ejection fraction, platelet aggregation inhibition, and antiarrhythmic effects (although in the latter case in particular, the results are contradictory and proarrhythmic properties have also been described in opposition).

Association studies

Before the results of randomized controlled trials on the use of omega-3 fatty acids were available, several association studies suggested beneficial effects of these fatty acids. Studies from the 1970s and 1980s, which collected data on Eskimos and attributed a lower incidence of coronary heart disease to the high consumption of fish there, have become known, although no causal relationship could be shown. It was merely an association. Subsequently, in addition to such cross-sectional studies, prospective cohort studies were also conducted in which cardiovascular risk was compared with the fish consumption of the study participants, in some cases over a long period of time. For example, a Dutch study in 1985 showed over a 20-year period that mortality from coronary heart disease in a cohort of 852 men was more than 50% lower with fish consumption of at least 30 g per day than in study participants with low fish consumption [2]. One of the largest published studies, the American “Nurse’s Health Study” with over 80,000 participants, was able to show a benefit with regard to coronary heart disease and associated mortality not only in women with regular fish consumption, but also in general with an increased intake of omega-3 fatty acids [3].

It is interesting to note that various association studies have shown that the beneficial effects of fish consumption are mostly due to the consumption of cooked fish, but not fried fish. The use of “harmful” saturated fatty acids during the frying process appeared to offset the beneficial effects of the fatty acids contained in the fish. For example, the large Women’s Health Initiative study with over 80,000 participants showed that the risk of heart failure was smaller in women with high consumption of baked or cooked fish, while consumption of fried fish was even associated with an increased risk of heart failure [4].

Intervention studies

The results of the association studies eventually led to the planning of various intervention studies to investigate the actual effect of omega-3 fatty acids. Unfortunately, recent studies have produced sobering results.

The ORIGIN trial, published in 2012, randomized over 12 000 patients with diabetes or prediabetes to an intervention of 900 mg of omega-3 fatty acids daily and compared this to placebo [5]. Over a mean observation period of more than six years, no differences in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality were observed. In May 2013, the data from the Italian “Risk and Prevention Study” were published. Study participants were women and men with multiple cardiovascular risk factors – such as the patient H.M. mentioned at the beginning [6]. Over five years, these were observed, and a benefit in terms of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality could not be shown. Also, any differential effects of different omega-3 fatty acids have often not been confirmed in large recent studies. Thus, a randomized trial compared the effect of EPA and DHA with that of ALA, with neither intervention showing a beneficial effect [7].

Omega-3 fatty acids – no or only minor effects?

Why have the large randomized trials of recent years had such difficulty showing protective influences of omega-3 fatty acids, despite so much evidence from experimental and association studies? One of the main reasons could be that in these randomized trials the number of cases was too small to show small effects, if any. This means that even more patients or subjects should have been included over a longer period of time. On the other hand, it has also become increasingly difficult to show small positive effects on the cardiovascular system: Over the last decades, the treatment of patients at high cardiovascular risk has improved quite significantly. Good cardiovascular treatment already at baseline makes it difficult to show a relatively small additional benefit.

The results of the American VITAL study, which will be published in about three years, are eagerly awaited. The aim of this study is to investigate the positive effects of administering omega-3 fatty acids in more than 20 000 patients. The VITAL trial is a primary prevention trial in patients without high cardiovascular risk and thus differs from most randomized trials in recent years.

International recommendations

Despite, or perhaps because of, the large amount of existing data on omega-3 fatty acids (see [8] for an overview), the recommendations of various international experts are not yet available.

organizations have remained relatively restrained and little evidence-based.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC), along with other cardiovascular disease prevention societies, recommends consuming fish at least twice a week, at least once of which should be oil-rich fish such as salmon, herring or mackerel. Taking higher doses of fish oil (2-4 g daily) is recommended in these guidelines only for the treatment of triglyceridemia [9].

The AHA (American Heart Association) guidelines are comparable and contain three important references: First, the consumption of fish naturally always has the positive effect that, in addition to the addition of omega-3 fatty acids, this also replaces other foods with a higher content of saturated and trans fatty acids. Secondly, it is important to note that the preparation of the fish should of course be done as far as possible without the addition of such fatty acids, i.e. there should be no frying or corresponding

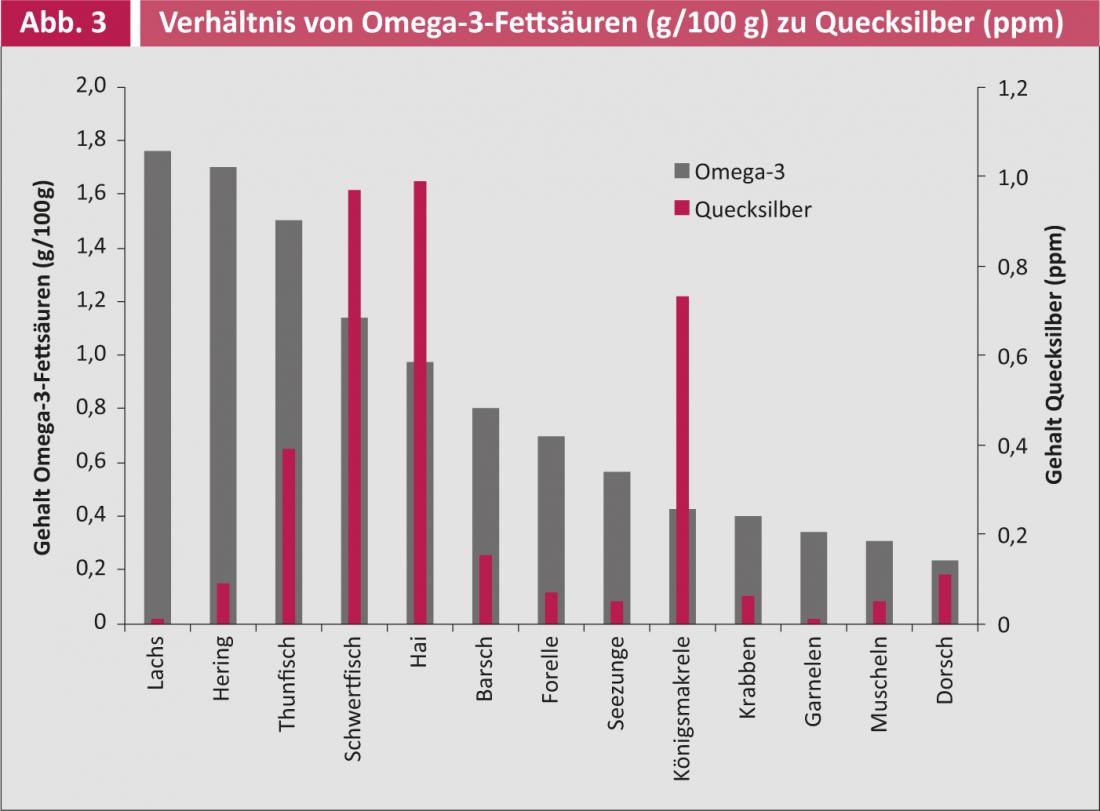

sauces can be dispensed with. Thirdly, the toxin content of fish, which unfortunately should not be underestimated nowadays due to increasing water pollution, should be considered – especially children or pregnant women should avoid fish with a high mercury content such as swordfish, shark or tuna (Fig. 3) [10].

Finally, the similar WHO recommendations cite the possibility of “vegetarian” intake of ALA, for example in the form of linseed oil.

Conclusion

The putative protective cardiovascular effects of omega-3 fatty acids from observational studies could not be confirmed in intervention studies. However, regular consumption of fish (1-2 times per week) is recommended by most major professional societies. Fish oil capsules are not part of the standard treatment or even prevention of atherosclerosis. Our patient H.M. could have saved the money for the capsules and better bought a cold water fish instead (opinion of the authors)…

MSc. Philipp A. Gerber

Literature:

- Simopoulos AP: Omega-3 fatty acids in health and disease and in growth and development. Am J Clin Nutr 1991 Sep; 54(3): 438-463.

- Kromhout D, et al: The inverse relation between fish consumption and 20-year mortality from coronary heart disease. NEJM 1985 May 9; 312(19): 1205-1209.

- Hu FB, et al: Fish and omega-3 fatty acid intake and risk of coronary heart disease in women. JAMA 2002 Apr 10; 287(14): 1815-1821.

- Belin RJ, et al: Fish intake and the risk of incident heart failure: the Women’s Health Initiative. Circ Heart Fail 2011 Jul; 4(4): 404-413.

- Bosch J, et al: n-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with dysglycemia. NEJM 2012 Jul 26; 367(4): 309-318.

- Roncaglioni MC, et al: n-3 Fatty Acids in Patients with Multiple Cardiovascular Risk Factors. NEJM 2013 May 9; 368(19): 1800-1808.

- Kromhout D, et al: n-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular events after myocardial infarction. NEJM 2010 Nov 18; 363(21): 2015-2026.

- Gerber PA, et al.: Omega-3 fatty acids: role in metabolism and cardiovascular disease. Current pharmaceutical design 2013; 19(17): 3074-3093.

- Perk J, et al: European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012): The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts) * Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2012 Jul; 33(13): 1635-1701.

- American Heart Association (AHA): Fish 101. 2013 [cited 2013 12 May]; Available at: www.heart.org/HEARTORG/GettingHealthy/NutritionCenter/Fish-101_UCM_305986_Article.jsp#benefits_vs_risks.