Patients with “Mild Cognitive Impairment” (MCI) have an increased risk of developing manifest dementia. The evidence on drug treatments that slow the progression of neurocognitive impairment is mixed. In terms of quality of life and adherence, treatment options with few side effects are advantageous. A multimodal treatment approach is most promising.

Dementia often begins insidiously and is often difficult to distinguish from age-related neurocognitive impairment in the early stages. Mild cognitive impairment (“MCI”) syndrome has been conceptualized as a prodromal or risk syndrome of dementia [1]. Affected individuals suffer from memory impairment, but everyday functions are not or only slightly impaired [2]. The classification of MCI as a clinical syndrome has changed over the years(box) [1]. In about 5-10%, MCI progresses to Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia; in others, cognitive abilities remain stable for a long time or improve again [3]. 8-14% of MCI patients develop dementia within one year [4]. Isolated episodic memory impairment as a leading symptom (“amnestic MCI”) is prognostically unfavorable [1].

|

“Mild Cognitive Impairment” (MCI). In the ICD-11 classification system, the diagnostic classification “mild neurocognitive disorders” exists [5,11]. According to the S3 guidelines, an MCI syndrome can be diagnosed on the basis of the clinical picture and with the inclusion of neuropsychological testing procedures [1]. Neuropsychological diagnosis should include tests of attentional performance and executive functions, including the domain of delayed recall, as the latter is considered an early indicator of the onset of AD [1,12]. Brief tests such as the MMST, DemTect, and TFDD do not have sufficient sensitivity for detecting MCI because they can lead to ceiling effects. As with dementia diagnosis, anamnestic information and consideration of the patient’s general health as well as life history and current sociocultural context are also relevant. Differentially, it is important to distinguish MCI as an expression of incipient neurodegenerative dementia from other possible causes such as vascular lesions, depressive episodes, medication side effects, and alcohol abuse [1]. |

Drug therapy in MCI: further studies needed.

Reduction of vascular, metabolic, toxic, and psychological risk factors is an important therapeutic goal in MCI, but findings are inconsistent regarding pharmacological treatment options. Based on studies to date, there is no drug therapy that has been clearly shown to be a disease-modifying intervention in MCI [5]. A 2020 review by Kasper et al. concludes that there is a lack of recommendations for the treatment of MCI and that international guidelines should place greater emphasis on evidence-based management of MCI [5]. Considering the multifactorial nature of the disease, a “multi-target” intervention seems to be more effective than focusing on a single target. A multimodal treatment approach, which includes lifestyle interventions – including diet, exercise, social activities, and mental training – in addition to symptomatic drug therapy, seems to be the most promising. In an update on the management of MCI, the American Academy for Neurology included the recommendation of regular exercise (at least twice a week) in its guidelines [14]. That patients with MCI may also benefit from psychotherapeutic interventions has been shown in studies that have demonstrated a benefit for cognitive-behavioral therapy approaches to alleviate mild cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms, among others [6]. With regard to symptomatic drug therapy options, it is important to also consider the quality of life factor and to advise treatment options with few side effects.

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: mixed evidence.

In a secondary analysis, Matsunaga et al. the efficacy and tolerability of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in patients with mild cognitive impairment (“MCI”) [7,8]. The meta-analysis included 14 double-blind randomized controlled trials (6 with donepezil, 4 with galantamine, 4 with rivastigmine) with a total of 5278 patients. The mean age was 70.3 years, and the mean study duration was 67.9 weeks. No significant overall effect of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors on the primary endpoint of “cognitive function in patients with MCI” was demonstrated. However, in the subgroup analyses for each agent, a very small effect of donepezil on cognitive function in patients with MCI could be demonstrated. Regarding the secondary endpoints, although treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors resulted in less frequent conversion to dementia-related syndrome than placebo (risk ratio [RR]: 0.76; number-needed-to-treat [NNT]: 20), according to subgroup analyses only galantamine had this small effect (RR: 0.68; NNT: 17). Overall, there was no effect of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors on overall clinical impression (CGI scores). According to subgroup analyses, only rivastigmine had a small effect on this.

Regarding tolerability, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors resulted in more frequent treatment discontinuations overall (RR: 1.25; Number-Needed-to-Harm [NNH]: 11) and treatment discontinuations due to side effects (RR: 2.14; NNH: 11). In addition, adverse effects were more frequent with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (RR: 1.10, NNT: 13). In the subgroup analyses, this was particularly true for donezepil and galantamine.

A study also published in 2019, which analyzed data from 2242 patients with a diagnosis of MCI and mild AD, concluded that the use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (ACh-i) did not improve the course of these diseases [9]. 34% of the 944 patients with Alzheimer-type MCI and 72% of the 1298 patients with a mild form of AD were treated with ACh-i. Evaluations revealed that cognitive deterioration was more pronounced after initiation of ACh-i therapy. This was true for both patients with Alzheimer-type MCI treated with ACh-i and those with a mild form of AD, compared with those patients who did not receive ACh-i.

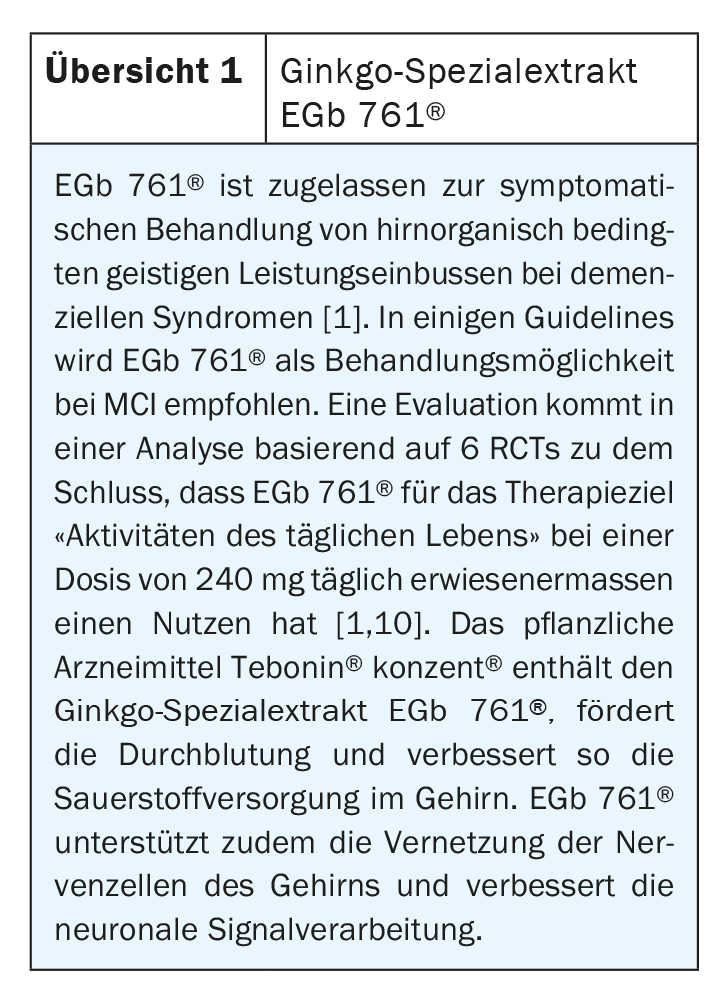

Overall, it is hoped that additional symptomatic and causal treatment options for MCI will be developed and evaluated in trials in the future. Current pharmacological treatment options for MCI include the special ginkgo extract EGb 761® (review 1) for symptomatic treatment of cognitive impairment and associated neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Literature:

- DGPPN/DGN: S3-Leitlinie “Demenzen”, 2016, long version. www.dgppn.de

- McDade EM, Petersen RC: Mild cognitive impairment: epidemiology, pathology, and clinical assessment. UpToDate 10/2015.

- Huber F, Beise U: Dementia. Last revised: 03/2017. www.medix.ch/wissen/guidelines/psychische-krankheiten/demenz (last call 23.03.2021)

- Mosimann UP, Annoni J-M: Dementia – early assessment of cognitive impairment. Swiss Neurological Society (SNS), 01.11.10, www.swissneuro.ch (last accessed 23.03.2021).

- Kasper S, et al: Management of mild cognitive impairment (MCI): The need for national and international guidelines. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 2020; 21 (8): 579-594.

- Simon SS, Cordas TA, Bottino CM: Cognitive therapies in older adults with depression and cognitive deficits: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015; 30(3): 223-233.

- Matsunaga S, Fujishiro H, Takechi H: Efficacy and Safety of Cholinesterase Inhibitors for Mild Cognitive Impairment:A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Alzheimers Dis 2019; 71(2): 513-523.

- Geschke K: Little effect with clear side effects. Neurology & Psychiatry 2019 (21): 14.

- Han J-Y, et al: Cholinesterase Inhibitors May Not Benefit Mild Cognitive Impairment and Mild Alzheimer Disease Dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2019; 33(2): 87-94.

- IQWiG (ed.): Ginkgo-containing preparations in Alzheimer’s dementia. Final Report A05-19B (Version 1.0, as of 9/29/2008). Cologne, IQWiG 2008.

- World Health Organization (WHO): ICD-11, International Classification of Diseases11th Revision, https://icd.who.int/en (last accessed Mar. 23, 2021).

- Bondi MW, et al: Neuropsychological contributions to the early identification of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychol Rev 2008; 18: 73-90.

- Medical Care Cooperation (McCare): Education: MCI and Dementia, www.mccare.com/education/mcidementia.html (last accessed Mar. 23, 2021).

- Petersen RC, et al: Practice guideline update summary. American Academy of Neurology 2018; 90 (3): Special Article, https://n.neurology.org/content/90/3/126 (last accessed Mar 24, 2021).

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(4): 32-33