Many skin diseases are accompanied by psychosocial stress, which can lead to considerable limitations in the quality of life. Dermatologists should be aware of risk factors and symptoms for maladaptive processing reactions and refer patients to psychologists/psychotherapists as needed. Ideally, psychological support is provided as part of a multidisciplinary team, but clearly defined referral pathways and close collaboration between dermatologists and psychologists/psychotherapists are also effective.

In addition to various biological functions as a boundary and sensory organ, the skin also fulfills important psychosocial functions. Visible skin disorders directly affect social interactions [1]. This can significantly affect the psychological well-being and quality of life of affected individuals as well as their families [2,3].

The issue of “stigma” is central to pediatric dermatology, as many stigmatizing skin conditions are congenital or occur in the first few years of life. The therapy of children with stigmatizing skin diseases plays out on different levels. As far as possible, doctors naturally want to try to treat visible skin conditions. While good therapies are available for some conditions, such as infantile hemangiomas, others, such as alopecia areata, are very difficult to treat therapeutically. It is important not to raise unrealistic expectations, as this can lead to great disappointment for those affected and make further treatment more difficult. Comprehensive care for patients with stigmatizing skin diseases includes not only medical treatment, but also psychological support as needed. The aim here is to reduce the extent of the burden caused by the skin disease in everyday life and thus to increase the quality of life of those affected and to enable the children to develop as positively as possible psychosocially despite stigmatizing lesions. It makes sense to work together with appropriate specialists on an interdisciplinary basis for this purpose. It often helps affected children and families to exchange information with other affected persons.

For some years now, there has been the so-called “Hautstigma Initiative”, which is led by an interdisciplinary team of psychologists and physicians from the Children’s Hospital in Zurich. Its goal is to empower children and adolescents with congenital or acquired skin disorders, as well as their families, and to prevent the stigmatization of those affected. The campaign website (www.hautstigma.ch) provides a valuable platform for information, exchange and networking among those affected. Two specially trained nurse practitioners also regularly offer individual camouflage makeup classes for adolescents with skin conditions (www.hautstigma.ch/camouflage).

Part 1: Common stigmatizing skin diseases in childhood.

In the following, typical stigmatizing skin lesions in childhood and adolescence and their therapeutic options are discussed in the first part of this two-part article by Regula Wälchli, MD, and Martin Theiler, MD. The second part of Dr. phil. Ornella Masnari and Prof. Dr. phil. Markus A. Landolt devotes himself to psychological aspects.

Infantile hemangiomas (IH)

IH are markedly common and occur in approximately 5% of all children. Quite characteristic is their growth behavior. Thus, they are absent at birth or present only as precursor lesions and begin to grow rapidly in the first one to three weeks. At the age of three months IH have already reached 80% of their maximum size. From the age of one year, the slow involution then begins, which is usually completed at the age of three to five years. However, this does not mean that IH disappear completely – most of them leave more or less visible traces.

While a proportion of IH cause functional limitations and require mandatory treatment for medical reasons, since the discovery of the excellent efficacy and good tolerability of topical and systemic beta-blockers [4], the aesthetic sequelae of IH have also become much more of a focus and increasingly IH are being treated for primarily aesthetic considerations. In doing so, it is sometimes not easy to foresee which IH will leave unsightly traces later. As a rule of thumb, wherever the dermis has been severely stretched, clearly visible anetoderma-like residuals will remain later. Thus, thick superficial hemangiomas with a steep angle of ascent from unaffected skin to hemangioma are particularly affected (Fig. 1) [5].

A large deep component, on the other hand, often recedes well later. Long-term visible scars always appear after ulcerations as well. Since the esthetic outcome depends primarily on the thickness of the hemangioma, therapy should be started as early as possible, i.e. within the first one to two months of life. Starting treatment after the sixth month of life usually has little effect on long-term outcome. For small IH at highly visible sites, topical beta-blockers (timolol) are appropriate, whereas for larger lesions, systemic therapy with propranolol is usually indicated. In unclear cases, topical treatment can also be started under close follow-up and, if the response is insufficient, switched to systemic therapy. Treatments for aesthetic reasons should always be discussed with the parents and the advantages and disadvantages weighed against each other.

Nevus flammeus (CM)

Capillary malformations (CM) are benign vascular malformations that are present at birth. They occur in approximately 0.3% of newborns, show proportional growth, and persist throughout life. Most often, CM occur in isolation. However, when localized to the frontal or temporal region, there is a greatly increased risk for the presence of Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS), defined as the clinical triad of facial CM, cerebral capillary venous malformation, and glaucoma [6]. In these cases, emergency ophthalmologic examination and cranial MRI are indicated. A somatic mutation in the GNAQ gene was recently identified as the cause of SWS and isolated CM [7].

Due to their benign nature, port-wine stains do not necessarily require treatment. However, many patients desire intervention. The therapy of choice is dye laser therapy (pulsed dye laser), which should ideally be started early in the face, i.e. from the tenth to twelfth month of life, in order to achieve an optimal therapy response. These laser therapies are performed in young children under short anesthesia. Extrafascial lesions can also be treated under surface anesthesia from the age of eight to ten years. For a good aesthetic result, several laser sessions (at least four to six sessions) are generally required.

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN)

Congenital melanocytic nevi are benign proliferations of melanocytes or melanocyte precursor cells that develop intrauterine and become visible at birth or, less commonly, within the first months of life. The incidence of CMN of any size is 1-2%, whereas CMN with an area greater than 20 cm2 are rare (incidence 1:500,000) (Fig. 2) [8].

In particular, large or multiple CMN (defined as more than one melanocytic nevus since birth) can lead to complications. In addition to malignant degeneration, possible CNS involvement either in the form of neurocutaneous melanocytosis (leptomeningeal or intracerebral melanosis, NCM) or in the form of CNS malformations (malformations, hydrocephalus, or non-melanocytic CNS tumors) represents a morbidity or morbidity risk. mortality risk. Genetic studies revealed that mutations in the NRAS gene are the cause of 80% of all cases of multiple CMN and NCM [9].

The overall risk of developing malignant melanoma on the floor of CMN is much lower than previously thought and correlates primarily with nevus size.

In multiple CMN, CNS involvement occurs in approximately 20%. This encompasses a wide spectrum of different CNS pathologies, which can clinically result in seizures, developmental retardation, and other neurological symptoms. In the presence of a CNS malformation or tumor, neurosurgical intervention may be necessary and therefore early imaging (MRI skull and spinal cord) by six months of age at the latest is part of the routine diagnosis in large and multiple CMN. Previously, it was thought that the clinical significance and prognosis of CNS involvement in CMN depended on the presence or absence of neurologic symptoms. According to new research, however, it has been shown that the underlying CNS malformation is crucial for prognosis – regardless of whether clinically symptomatic or not [10].

CMNs impose a psychological burden on patients and families. Surgical measures are of great importance in the treatment of CMN, but the indication for them has to be weighed up individually on a case-by-case basis. To date, it is not clear whether excision of a large nevus/giant nevus significantly reduces or eliminates the risk of developing melanoma in the patient overall. Thus, according to these findings, the only compelling indication for surgical excision is suspected malignancy. Nevertheless, excision is desired by a large proportion of patients and parents, especially if the lesions are located on the face and/or have marked hypertrichosis. In any case, the expected aesthetic result after surgical intervention should be critically assessed against the nevus. Research shows that three quarters of patients with large CMN prefer scar to nevus, but about one quarter regret surgery that has taken place. Therefore, the indication for surgical therapy must be evaluated individually and patients must be cared for as part of a multidisciplinary team (pediatric dermatology, pediatric plastic surgery, and pediatric psychology).

Alopecia areata (AA)

AA, along with trichotillomania and tinea capitis, is the most common cause of hair loss in childhood. Small areas have an excellent prognosis. On the other hand, extensive forms often do not result in full hair regrowth. Since early onset is also associated with poor prognosis, we are quite frequently confronted with children affected by long-term (sub)total alopecia. The suffering of patients with alopecia is often particularly high because in our society it is associated with cancer, disease and vitamin deficiency. Hair is also an important tool in social interaction.

Smaller areas usually heal within six to twelve months with or without therapy, classically using potent topical steroids. Intralesional use is also an option for older children. For extensive, rapidly progressive forms (>30% of scalp affected), we often use methylprednisolone pulse therapies. While these are usually effective in the short term, their impact on long-term outcome is controversial and a recent study we conducted showed no definite effect in this regard with high recurrence rates [11]. Subsequent treatment with methotrexate may be useful [12] and is performed by us in selected cases after careful risk assessment. For chronic forms, topical immunotherapy with diphenylcyclopropenone (DCP) may also be considered from the age of nine to ten years.

Even with great therapeutic effort, treatment failure is common, so psychological support for patients is especially important. In addition to general aspects of stigmatization, practical questions such as wig yes/no, behavior in sports or swimming lessons, make-up/artificial eyelashes in the case of corresponding affliction, etc. are central aspects in the care.

Vitiligo

Similarly to AA, vitiligo is also a disease. The suffering is especially high in patients with dark skin types, because vitiligo is more visible and light patches are associated with severe diseases that occur in the corresponding countries of origin (e.g. leprosy, onchocerciasis). Unfortunately, we often see only an insufficient response to therapy in vitiligo as well. While depigmented areas on the face and trunk in our experience in children respond quite reliably to long-term treatment with topical steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, or even UV light, therapeutic manipulation of lesions on the acras is usually very limited. Likewise, genital infestation, which is often very distressing for adolescents, is difficult to treat. In contrast, segmental vitiligo, which is more common in children, is not more refractory to treatment than the classic form in our experience, contrary to the current literature.

Since vitiligo is not associated with structural changes in the skin, it is readily amenable to medical camouflage. This represents a sensible measure for individual affected persons.

Part 2: Psychosocial stress in skin diseases in childhood and adolescence.

Psychosocial factors play an important role in skin diseases at various levels. Roughly speaking, three constellations can be distinguished:

- Primary mental disorders accompanied by skin symptomatology (e.g., body dysmorphic disorder).

- Skin diseases which are influenced by psychological factors with regard to manifestation and course (e.g. psoriasis)

- Skin diseases leading to secondary psychological distress (e.g., social anxiety due to skin disease).

This article is limited to the third point, focusing in particular on experiences of stigmatization and psychosocial stress in childhood and adolescence.

Experiences of stigmatization in skin diseases.

In addition to various biological functions as a boundary and sensory organ, the skin also fulfills important psychosocial functions. Numerous studies show that a skin condition shapes both a person’s self-perception and how others perceive him or her, and influences social interactions. For example, a survey of school classes showed that children with a facial skin abnormality (e.g., a port-wine stain or infantile hemangioma) were rated significantly more negatively by 8-17-year-old students on various traits (e.g., attractiveness, likability, cheerfulness, popularity, and intelligence) than children without a skin abnormality. In addition, many students surveyed reported feeling uncomfortable interacting with children with a skin condition and were less likely to engage in social interactions with them [1].

Accordingly, several studies indicate that children and adolescents with appearance disorders face significant psychosocial challenges: Affected individuals often report being stared at, called names, bullied, shunned, or excluded [3,13]. Such unpleasant social reactions can negatively affect psychological well-being, self-esteem, and subjective quality of life, leading to psychological sequelae such as anxiety, social withdrawal, or depressiveness [2,3,14].

The fear of being spoken to about the skin change or even rejected because of it causes some affected persons to hide the skin disease and to avoid situations in which the skin conspicuousness would be visible (e.g. in the swimming pool). Such avoidance behavior reduces anxiety and distress in the short term, but in the longer term it prevents the child from developing adequate coping skills and contributes to the maintenance of anticipatory anxiety and generalization of the problem.

It should be kept in mind that not all affected individuals experience their skin disease and related psychosocial challenges as equally stressful. There are significant interindividual differences – both in the assessment and in the management of the situation.

Factors influencing psychosocial stress

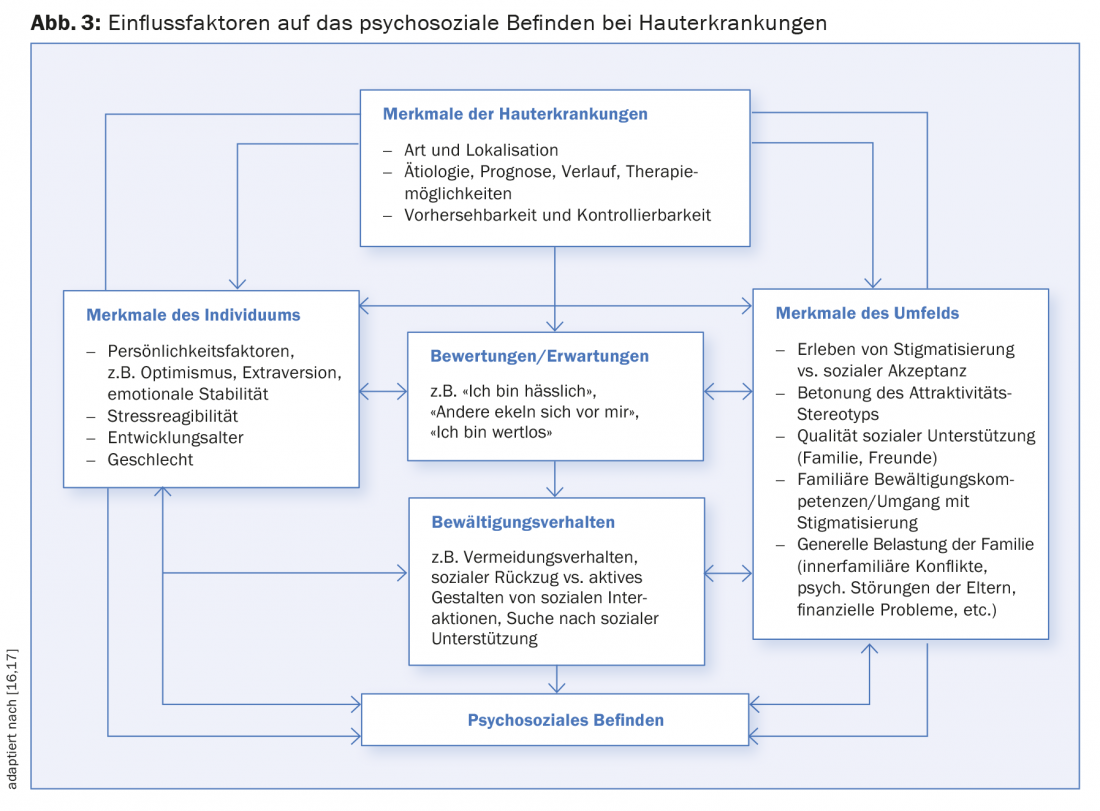

How a child copes with a skin disease and its consequences depends on a variety of factors: the specific burden of the disease, his or her personal preconditions, as well as the social value of the skin disease and the reactions of the environment. Figure 3 provides an overview of possible influencing factors.

Both empirical findings and clinical practice repeatedly show that psychological well-being and subjectively perceived quality of life are determined less by medical diagnosis or objective disease severity than by psychosocial factors. Even if the size and visibility of a skin disease influence the extent of stigmatization [13], it is not possible to draw conclusions about the psychological burden from these factors. Individual evaluation processes and coping strategies are much more significant. Good social skills help to actively shape and successfully manage social interactions.

In addition to how the environment reacts to the skin disease, the extent of social support that the child experiences is also decisive. How parents handle the situation has a big impact on how children cope. Empirical findings suggest that family factors such as parental mental health, a supportive family climate, and low interfamily conflict predict lower expression of emotional or behavioral problems in the child [15].

Psychosocial stress also depends on the child’s developmental age. While a young child is still hardly aware of the social implications of his or her skin disorder, difficulties arise more frequently in kindergarten and school age, when the child increasingly comes into contact with the non-family environment and is confronted with curious questions regarding his or her skin disorder. Puberty is considered to be a particularly vulnerable phase in which a number of developmental demands (identity development, establishment of extra-familial relationships, independence from parents, preparation for work, etc.) are pending, which can interact unfavorably with illness-related stresses.

The decisive factor for the individual load is always the balance between the requirements and the available resources.

Psychosocial care and implications for dermatology.

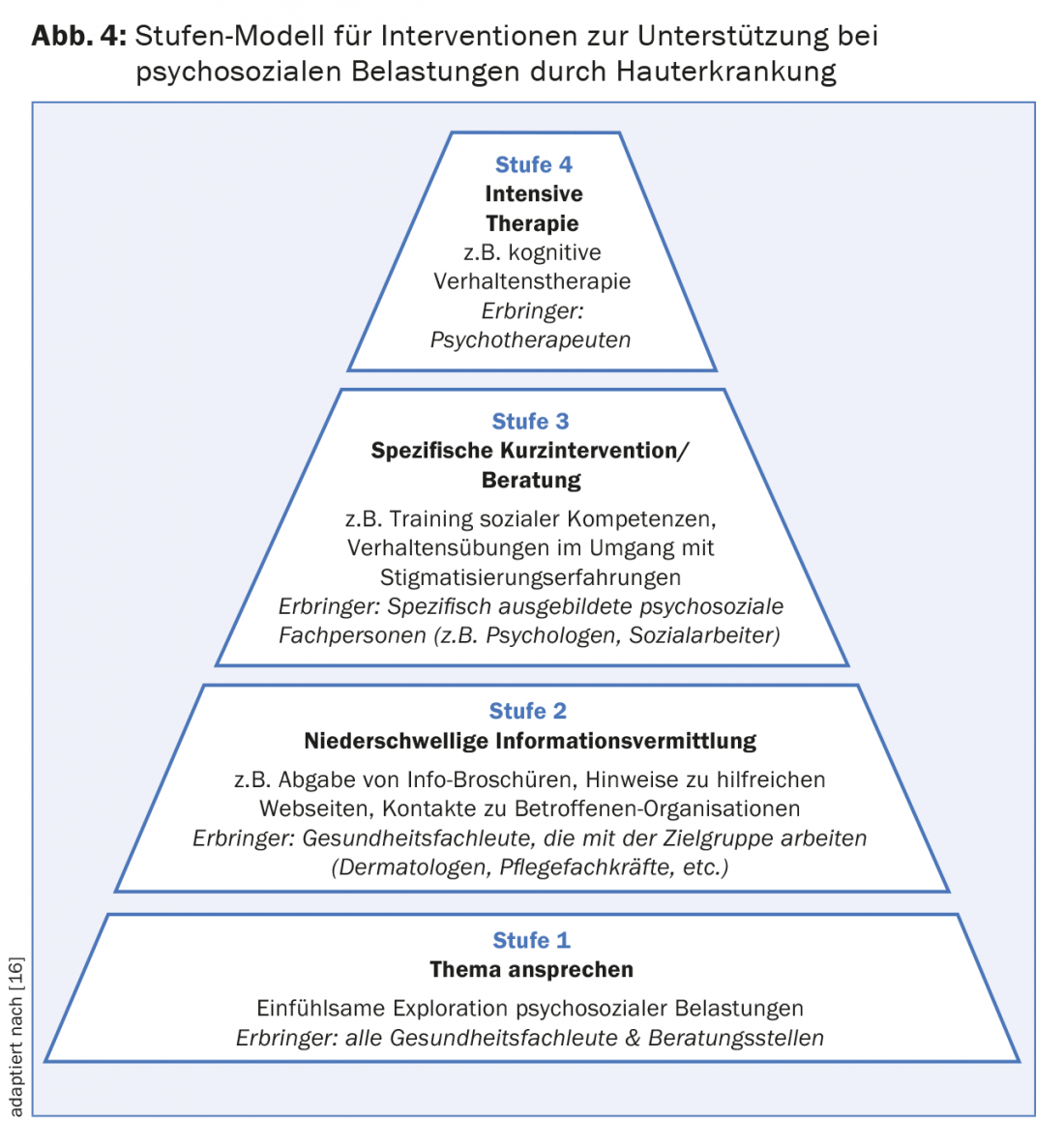

With regard to psychosocial support for affected persons, a model of stepwise care is recommended (Fig. 4).

First, it is important to consciously ask patients with skin diseases about psychosocial difficulties and to address them sensitively (stage 1). The question of how others react to the skin disease and how those affected deal with it already provides good indications of the stress experience and available coping resources. The majority of those affected demonstrate adequate coping skills and do not require psychological care. If certain uncertainties or concerns become apparent, low-threshold information (e.g. brochures, references to helpful websites or associations of affected persons) can be given (level 2). If affected persons or their relatives report significant stress or if there are indications of maladaptive processing reactions, the possibility of psychological counseling or specific brief interventions (level 3) should be pointed out. Only a small proportion of patients require intensive psychotherapeutic treatment (level 4).

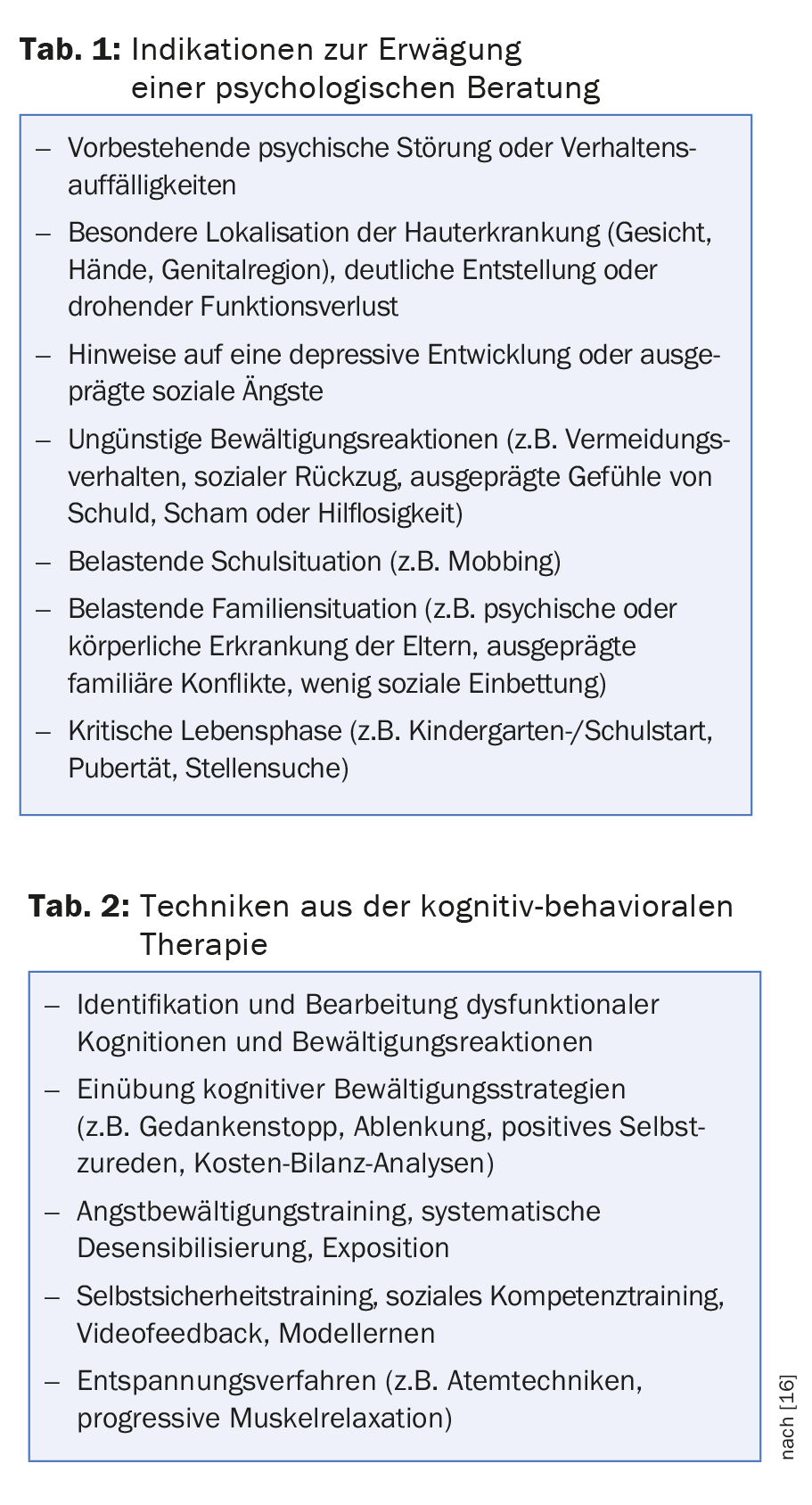

The main indications for considering psychological support are shown in Table 1.

Specific psychological interventions

The aim of psychological counseling is to support affected children and adolescents as well as their relatives in the areas they perceive as stressful and thus to improve their quality of life. From a clinical psychological perspective, the following content is central: Coping with experiences of stigmatization (e.g., dealing with prying questions or teasing) and working through dysfunctional beliefs (e.g., “they stare at me to annoy me”) and distressing feelings such as helplessness, anger, shame, guilt, or anxiety. Cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques aimed at changing dysfunctional evaluations or behaviors are particularly suitable for this purpose (Table 2).

In order for a child to feel comfortable in social situations, it is essential that they learn strategies as early as possible on how to respond to curious or even dismissive behavior from others. Self-confidence or social skills training can be helpful in this regard: In the protected setting of therapy, for example, typical problem situations and suitable ways of reacting are practiced in role play. For example, the therapist can play a naughty child who makes negative comments about the skin abnormality, and the child can practice how to respond. Behavioral exercises can also be helpful to practice appearing confident (posture, eye contact, etc.) and actively managing social interactions.

A helpful strategy for dealing with inquisitive questions, for example, is the so-called “explain-reassure-distract” strategy: First, you give a brief explanation, followed by reassurance (e.g., “is not contagious”), and then you deliberately steer the conversation to another topic. The strategy can be used by the child concerned as well as by parents or teachers. Below are two examples: “I have eczema. It makes my skin red and itchy, but it’s not contagious. Shall we draw a picture together?” “It’s called a port-wine stain. I was born with it. It’s just a red mark, it doesn’t hurt and it doesn’t bother me. Do you like playing soccer too?”

Parents, too, must learn to successfully manage stigmatization experiences – not only for their own well-being, but also because their behavior serves as an important model for the child. For example, a mother who notices other children staring and whispering at her child on the bus might approach them and say, “Kevin burned himself when he was a little kid. That’s why he has a scar. But now he is fine. We don’t like it when other people point and whisper about us. We’d rather you come up to us, say hello, and ask a question if you’re curious.”

The key idea is that you can prepare for both curious questions and dismissive reactions. It is worthwhile to practice various responses and reaction options with the child until they feel natural. If the child has one or two answers at hand, the situation loses its threatening character. Actively shaping social interactions also reinforces a sense of control.

To prevent psychosocial difficulties, it is also important that, for example, the start of kindergarten or a change of school are well prepared. We recommend that parents contact the teacher ahead of time and inform them of the skin abnormality and discuss with them how to respond to curious glances or questions from classmates. Sometimes it can also be useful to send an informational letter to the parents of classmates. Proactive communication helps to prevent false prejudices or fear of contact. Further information can be found on our website www.hautstigma.ch.

Literature:

- Masnari O, et al: How children with facial differences are perceived by non-affected children and adolescents: perceiver effects on stereotypical attitudes. Body image 2013; 10: 515-523.

- Masnari O, et al: Stigmatization predicts psychological adjustment and quality of life in children and adolescents with a facial difference. J Pediatr Psychol 2013; 38(2): 162-172.

- Rumsey N, Harcourt D: Visible difference among children and adolescents: Issues and interventions. Developmental Neurorehabilitation 2007; 10(2): 113-123.

- Leaute-Labreze C, et al: A randomized, controlled trial of oral propranolol in infantile hemangioma. N Engl J Med 2015; 372(8): 735-746.

- Luu M, Frieden IJ: Hemangioma: Clinical Course, Complications, and Management. Br J Dermatol 2013; 169(1): 20-30.

- Waelchli R, et al: New vascular classification of port-wine stains: improving prediction of Sturge-Weber risk. Br J Dermatol 2014; 171(4): 861-867.

- Shirley MD, et al: Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med 2013; 368(21): 1971-1979.

- Castilla EE, da Graca Dutra M, Orioli-Parreiras IM: Epidemiology of congenital pigmented naevi: I. Incidence rates and relative frequencies. Br J Dermatol 1981; 104(3): 307-315.

- Kinsler VA, et al: Multiple congenital melanocytic nevi and neurocutaneous melanosis are caused by postzygotic mutations in codon 61 of NRAS. J Invest Dermatol 2013; 133(9): 2229-2236.

- Waelchli R, et al: Classification of neurological abnormalities in children with congenital melanocytic naevus syndrome identifies MRI as the best predictor of clinical outcome. Br J Dermatol 2015. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13898.

- Smith A, et al: High Relapse Rates Despite Early Intervention with Intravenous Methylprednisolone Pulse Therapy for Severe Childhood Alopecia Areata. Pediatr Dermatol 2015; 32(4): 481-487.

- Hammerschmidt M, Mulinari Brenner F: Efficacy and safety of methotrexate in alopecia areata. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia 2014; 89(5): 729-734.

- Masnari O, et al: Self- and parent- perceived stigmatization in children and adolescents with congenital or acquired facial differences. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery 2012; 65(12): 1664-1670.

- Koot HM, et al: Psychosocial sequelae in 29 children with giant congenital melanocytic naevi. Clin Exp Dermatol 2000; 25(8): 589-593.

- Dennis H, et al: Factors promoting psychological adjustment to childhood atopic eczema. Journal of Child Health Care 2006; 10(2): 126-139.

- Clarke A, et al: CBT for Appearance Anxiety: Psychosocial Interventions for Anxiety due to Visible Difference. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell 2014.

- Landolt M: Childhood psychotraumatology: basic principles, diagnosis and interventions, 2 edn. Göttingen: Hogrefe 2012.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2015; 25(4): 22-28