Severe drug allergies can be potentially life-threatening, so early detection and treatment is very important. In many cases, these are rather harmless exanthems. However, in 2-5% of cases, these are potentially very dangerous. These include toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Drug allergies: subdivision

Hypersensitivity to medications is common. In many cases, these are rather harmless exanthems. However, in 2-5% of cases, these are potentially very dangerous. A distinction is made between predictable, i.e. pharmacologically induced reactions (type A), and unpredictable, either allergic or pseudo-allergic reactions (type B) distinguished. Type A reactions account for approximately 80% of all adverse reactions and, unlike type B reactions, are dose-dependent. Allergic (type B) Reactions are based on an immune response against the drug in question. According to Coombs and Gells, these immune responses are divided into 4 categories, each corresponding to different mechanisms (IgE-, T-cell-. immune complex-, or IgG-Fc receptor-mediated). Clinically, this manifests itself in very different pictures, ranging from urticaria and contact dermatitis to anaphylactic reactions and bullous skin reactions. While some drugs show a particular clustering for allergy types, potentially (almost) any drug can cause an allergy.

The main severe drug allergies

Among the severe drug allergies are

- anaphylaxis,

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and its maximum variant, toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN),

- erythema multiforme major and

- DRESS (Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms).

The “non-severe” reactions, which include maculopapular drug exanthema, AGEP (Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis), SDRIFE (symmetric drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema), are not discussed here.

Anaphylaxis

Anaphylaxis is a type I reaction, also called an immediate type reaction, in which the drug is recognized by IgE antibodies, resulting in a massive histamine release after they dock with mast cells. The symptoms of anaphylaxis are itching, urticaria, flushing, angioedema (degree I), nausea, vomitus, convulsions, rhinorrhea, hoarseness, and dyspnea (grade II), defecation, laryngeal edema, bronchospasm, cyanosis, and shock (grade III) and respiratory and circulatory arrest (grade IV). Typically, 2 or more organ systems are involved. This acute form of drug allergy usually develops within minutes of ingestion or administration; common triggers include beta-lactam antibiotics, NSAIDs, muscle relaxants, and disinfectants such as chlorhexidine.

Warning signs here are the appearance of wheals, angioedema and/or general symptoms after a few minutes to a maximum of 1-2 hours after drug administration, sometimes associated with palmoplantar pruritus and/or metallic taste in the mouth.

Anaphylaxis requires immediate action: Guideline-based (depending on severity) administration of corticosteroids, antihistamines, and epinephrine, if necessary; monitoring for up to 8 hours after resolution of severe symptoms is reasonable and therefore often requires hospital treatment and monitoring. Due to the acute onset and course requiring immediate emergency treatment, please refer to detailed instructions prepared elsewhere.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN)

SJS and TEN are bullous drug reactions usually with mucosal involvement that differ in severity, i.e., spread to the body surface (<10% in SJS, >30% in TEN). These are relatively rare reactions (incidence about 1-2 cases per million per year), but are associated with very high morbidity and also mortality. In contrast to anaphylaxis, SJS/TEN are type IV, so-called late type reactions, in which not antibodies but (mainly cytotoxic) T cells mediate the allergic reaction. Clinically, this means that sensitization must occur first, i.e. symptoms may develop within 7-21 days with initial exposure and earlier with re-exposure. Major triggers include sulfonamides, allopurinol, tetracyclines, anticonvulsants, and NSAIDs.

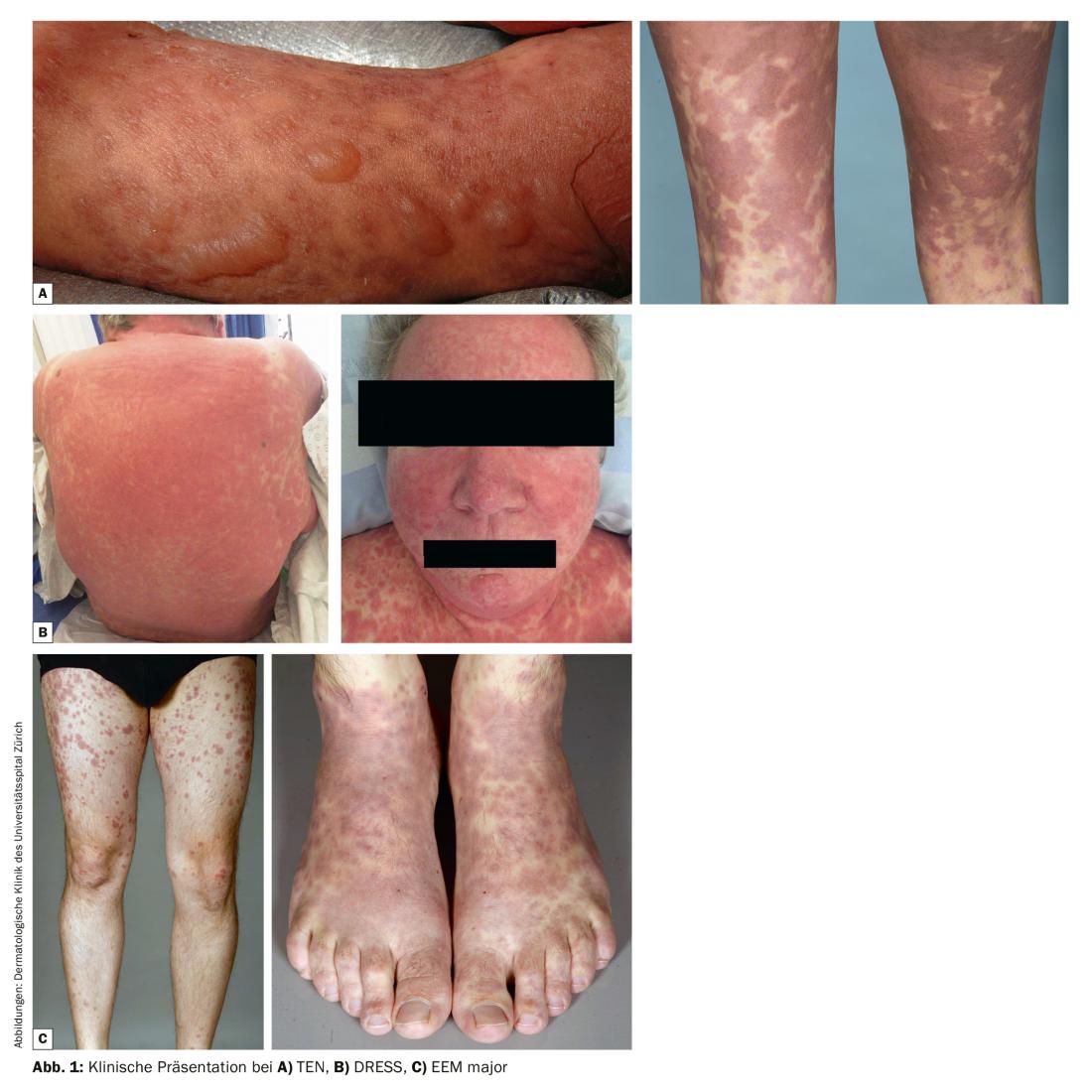

A macular, erythematous, livid exanthema forms on the skin, as well as bulging blisters and skin detachment, which can progress very quickly (within hours). (Fig.1A). The blistering usually also affects the mucous membranes (conjunctival, enoral, genital) which manifests itself here also in the form of dysphagia, eye burning and genital burning. Diffuse burning/pain on the skin is often described by SJS/TEN patients even before blisters form. In most cases, patients are in a reduced general condition. The most feared acute complications include sepsis caused by superinfection and hemodynamic destabilization. In up to 30% of patients, the course of the disease is lethal. Diagnosis is based on the clinic, history, and histology.

Due to the rarity of SJS/TEN, it is very difficult to conduct translational research studies and clinical trials with sufficient power. However, these are imperative due to the potential lethality of the reactions and many unanswered questions in the field. The team of the Department of Dermatology at the University Hospital Zurich, together with colleagues from France, the USA and Japan, have therefore established an international registry for accurate and standardized documentation and tissue collection of SJS/TEN cases worldwide (www.irten.org). Our goal is to contribute to a better understanding of the pathomechanisms and potential treatment of SJS/TEN and its late sequelae.

Erythema exsudativum major (EEM major)

Although the distinction from the SJS/TEN is still controversial, the EEM is considered a separate entity. EEM is less dangerous compared to SJS/TEN, but can still be very pronounced on the skin. An underlying type IV (T cell) reaction is discussed. EEM is often accompanied by an infection, especially herpes simplex. Clinically characteristic are cocard-like lesions (Fig. 1C) with a zonal structure, i.e., livid center, a recessed central zone, and erythematous rim (Fig. 1C) . The diagnosis of EEM is based on clinic, history and, if necessary, histology and especially viral smears.

The minor variant of EEM (without mucosal involvement) must be distinguished from EEM major, which often occurs in the context of a herpes infection or otherwise parainfectious and is only rarely caused by medication.

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms – DRESS

A comparatively new entity among severe drug allergies is the so-called DRESS, originally also called carbamazepine-phenytoin hypersensitivity syndrome (Fig. 1B). DRESS is a type IV reaction caused mainly by T-helper cells, which is usually accompanied by an additional “danger signal”, usually in the form of a reactivation of viruses (especially HHV6). In terms of time course, DRESS is characterized by the fact that it usually develops weeks to months after the start of medication. DRESS has been most frequently described with anticonvulsants (especially carbamazepine and phenytoin), but also dapsone (sulfonamides), barbiturates, and vemurafenib/cobimetinib. The clinical manifestations of DRESS are very heterogeneous and range from macular exanthema, pustules, erythroderma to blistering (the so-called TEN-like DRESS). Diagnostically relevant is the association with facial swelling, lymph node swelling, and fever. DRESS is dangerous because of organ involvement, which can lead to organ failure and death: Hepatitis is most common, but myocarditis, nephropathy, CNS and GI involvement can also occur.

The diagnosis of DRESS is based on a combination of clinical criteria (exanthema, facial swelling lymph node swelling, fever) and laboratory findings of eosinophilia (>12%), atypical lymphocytes, and laboratory parameters suggestive of organ involvement, particularly AST/ALT elevation and creatinine increase (and reduced eGFR).

Most important warning signs in the clinic

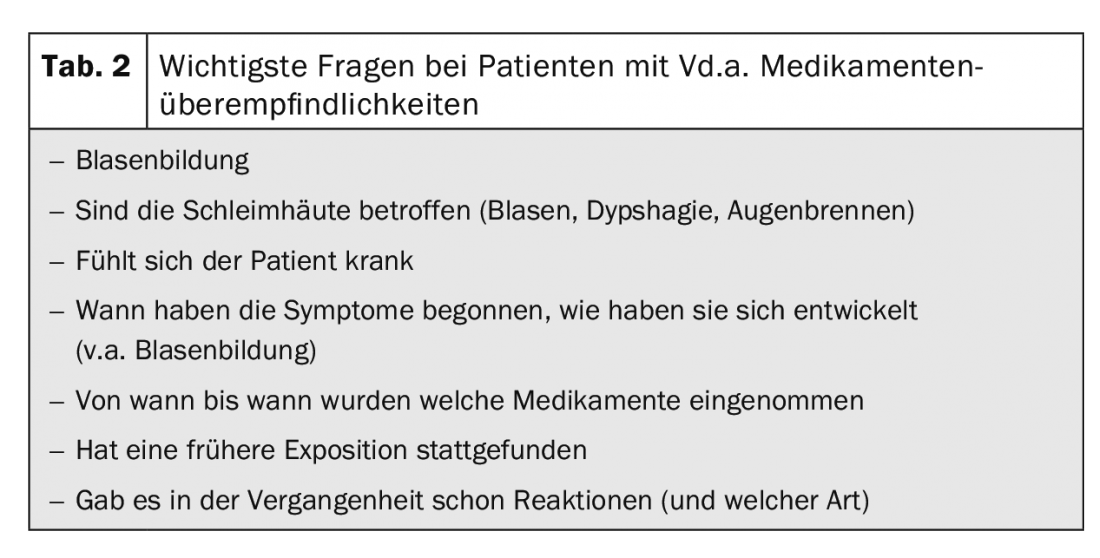

The recognition of warning signs in drug allergies is clinically very relevant, as early recognition and consequently adequate treatment are of great prognostic importance, i.e. can prevent organ damage and a potentially lethal course. Differentiating between innocuous and severe allergic drug reactions can be difficult even for a trained eye. This makes it all the more important to address some clinical and anamnestic clues in such patients (Tab. 1, Tab. 2).

The question of blistering and mucosal involvement should be a central part of the history. Burning of the skin, eyes, and oral and genital mucosa and dysphagia should also be explicitly asked about. These symptoms provide important clues to mucosal involvement. Especially burning or pain of the skin is typical for SJS/TEN, but much less observed in “banal” drug exanthema. The question of onset and spread of the skin lesions is also an important clue, as there can be very rapid progression, particularly in SJS/TEN. Asking about the timing of previous medication use is important in identifying potential triggers and “at-risk” medications (1. What exactly, 2. Since when or until when) and in narrowing down reactions. It is also important to ask about previous exposure and the symptomatology at that time, as reactions can be more severe and rapid with re-exposure.

According to the points described above, vital signs should be determined clinically, the entire skin and mucous membranes should be examined, and lymph nodes should be palpated. In dermatological status should also be tested the so-called Nikolski sign: Here we test by lateral pressure exerted with the finger on unaffected skin (without blisters) whether the skin is detached (Nikolski I) and whether an existing bladder can be displaced by applying pressure (Nikolski II). Also an internistic status incl. Determination of vital signs should be done. Particular attention should be paid to mucosal involvement, blistering (and positive Nikolski’s sign), lymph node and facial swelling, and fever and abnormal vital signs, as mentioned earlier.

Laboratory chemistry should include a blood count incl. manual differentiation: This is important because marked eosinophilia is a “red flag” and indicates a severe reaction and, depending on its severity, carries the risk of serious organ damage such as potentially lethal eosinophilic myocarditis. Atypical lymphocytes are another clue to the diagnosis of DRESS. CRP should also be determined. With regard to potential organ damage (especially in DRESS), liver (AST, ALT, bilirubin) and kidney (creatinine, eGFR) values should be determined as a first step.

Suspicion of a severe drug allergy: What now?

If a severe drug allergy is suspected, contact should be made immediately with the dermatological service of a center hospital in order to coordinate the further procedure: Therapeutically, the most important thing is to stop/replace probable triggers (and cross-reacting substances) immediately, taking into account or covering the primary indication, of course. Further diagnostics (biopsy, blood cultures, smear, etc.), therapy and transfer of the patient should be initiated immediately as agreed, as a delay can have prognostic consequences.

Even in the absence of warning signs, the potential trigger should be discontinued/substituted (unless there is a vital indication) and direct consultation with a dermatologist should be made.

Severe drug allergies: Acute and follow-up treatment

Acute treatment of TEN and, depending on the severity, DRESS patients is carried out in the (burn) intensive care unit by an interdisciplinary team. In SJS/TEN, “best supportive care” for wound treatment, prevention of superinfection, and hemodynamic stabilization, as well as adjuvant treatment (e.g., with intravenous immunoglobulins, TNF-alpha inhibitors, or cyclosporine), is provided. In DRESS, high-dose glucocorticosteroids (as well as symptomatic treatment). EEM major is also treated with systemic glucocorticosteroids.

The allergological workup in all patients with St.n. severe drug allergies is ideally performed at the earliest 4-6 weeks up to 6 months after resolution and includes serological (serologies, lymphocyte transformation test, basophil activation test) and/or skin testing (prick, intracutaneous and epicutaneous tests, sometimes with late reading after 24-48 hours) depending on the reaction type.

Patient follow-up should also be a high priority and involve teams from different disciplines. In DRESS patients, treatment must be phased out over a long period of time and under appropriate controls, otherwise the disease will flare up again. In particular, patients affected by SJS or TEN suffer not only from the extremely severe and potentially lethal course of the disease, but also from the sometimes severe and often very limiting late sequelae. These often include psychiatric sequelae, especially in the form of Post-Traumatic Stress Disease (PTSD), in addition to e.g. hyper- and hypopigmentation, scarring of the sclerae or in the genital area.

Take-Home Messages

- Severe drug allergies include: Anaphylaxis (type 1 reaction), SJS / TEN, DRESS, EEM major.

- Severe drug allergies can be potentially life-threatening, so early detection and treatment is very important

- Most important clinical warning signs include blistering, mucosal involvement, extensive expression, facial and lymph node swelling, reduced AZ, and abnormal vital signs

- An initial laboratory should include a blood count with microscopic differentiation, liver and kidney values, and CRP

- At Vd.a. severe drug allergy: contact dermatology of a center hospital immediately, in case of TEN contact a center with a burn intensive care unit.

Further reading:

- Mockenhaupt M: 2014. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: clinical patterns, diagnostic considerations, etiology, and therapeutic management. Semin Cutan Med Surg 33: 10-16.

- Deuel J, Schaer D, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Vallelian F: [CME. Severe cutaneous drug reaction]. Practice 2014; 15; 103(21): 1231-1243.

- Leaute-Labreze C, Lamireau T, Chawki D, et al: 2000. Diagnosis, classification, and management of erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Arch Dis Child 83: 347-352.

- Illing PT, Vivian JP, Dudek NL, et al: 2012. immune self-reactivity triggered by drug-modified HLA-peptide repertoire. Nature 486: 554-558.

- Nassif A, Bensussan A, Boumsell L, et al: 2004. toxic epidermal necrolysis: effector cells are drug-specific cytotoxic T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol 114: 1209-1215.

- Viard I, Wehrli P, Bullani R, et al: 1998. Inhibition of toxic epidermal necrolysis by blockade of CD95 with human intravenous immunoglobulin. Science 282: 490-493.

- Kardaun SH, Jonkman MF: 2007. Dexamethasone pulse therapy for Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Acta Derm Venereol 87: 144-148.

- Brockow K1, Pfützner W2: Cutaneous drug hypersensitivity: developments and controversies. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019 May 22. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000548. [Epub ahead of print]

- Pichler WJ. Immune pathomechanism and classification of drug hypersensitivity. Allergy. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1111/all.13765

- Phillips EJ, Bigliardi P, Bircher AJ, et al: Controversies in drug allergy: testing for delayed reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019 Jan;143(1): 66-73.

- www.ck-care.ch/documents/10181/14458/Anaphylaxis_HandelnimNotfall_20180908.pdf/58b48ad9-7c7e-4171-b090-48fa41ceb115 und www.ck-care.ch/documents/10181/14458/Anaphylaxie_NFP_KinderJugendliche_20190117_1.pdf/02705bda-e424-4241-9e14-d0a648450c09).

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2019; 29(4): 8-12