Ergometry is a commonly performed test in practice, where the assessment of blood pressure is a fundamental part of the interpretation of the test result. An exaggerated blood pressure response (exercise-induced hypertension) is associated with a certain degree of uncertainty with regard to prognostic and therapeutic consequences.

Physical stress testing on a bicycle or treadmill is a very common test performed in the primary care provider’s and cardiologist’s office. The assessment of blood pressure (BP) during this examination is a fundamental part of the interpretation of the test result. Whereas ischemia-induced BP drop is known to be an unfavorable sign, the assessment of an exaggerated BP response (exercise-induced hypertension, BelHT) is fraught with uncertainty as to prognostic and therapeutic consequence. The (physiological or overshooting) BP increase with exercise leads to the need to balance the benefits and potential hazards of exercise in patients with arterial hypertension (HT), especially in sports activities with high static, isometric loading. Finally, athletes can also be affected by HT, which entails some special features in clarification and therapy.

Normal circulatory behavior under load

A dynamic, physical activity increases the metabolic demand of the working muscles. There is therefore a redistribution of blood in favor of the muscles at the expense of the inactive organs. This redistribution is controlled by local and systemic vasodilation of arterioles in the consuming organ and results in a decrease in total peripheral resistance (TPR). At the same time, cardiac output (CV) is increased via an increase in sympathetic activity, heart rate, myocardial contractility, and relaxation. Since HZV increases proportionally more than TPR decreases, according to the equation (arterial mean pressure = HZV × TPR), there is an increase in arterial mean pressure. While diastolic BP remains relatively constant or even decreases under continued stress, systolic BP rises continuously to maximum values that depend on age, sex, and other factors (Fig. 1).

Exercise Hypertension

Definition: There is currently no general consensus regarding the definition of a BelHT. Many studies are based on the stress BP distributions of the studied population, which is difficult to translate into clinical practice. However, the systolic percentile curves for maximal exercise BP suggest a systolic BP >210 mmHg for men and >190 mmHg for women as, in our opinion, a reasonable “cut-off” [2], which is supported by numerous data.

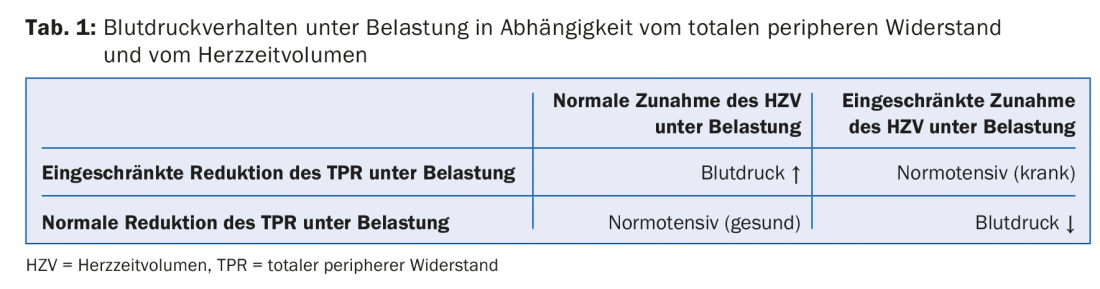

Mechanism: BelHT occurs when TPR does not decrease sufficiently under load and, together with the adequately increasing HZV, leads to an increase in BP. Impaired endothelial vasodilation plays a major role in the pathomechanism of impaired TPR reduction [3]; in addition, increased vascular stiffness is involved in the development of BelHT, especially in older individuals [3]. Furthermore, angiotensin II release is increased during exercise in individuals with a BelHT compared to those without a BelHT [3]. Importantly, a normotensive BP response to exercise does not automatically equate to a physiological BP response, because with impaired reduction in TPR and HZV, the BP response may also be normal (Table 1).

Prognostic significance in “healthy” individuals: Numerous studies have examined the development of HT in normotensive individuals with BelHT and have found a consistent association of BelHT with the future development of HT despite significant methodological differences among these studies [4]. This association is particularly evident in individuals with resting BP in the prehypertensive range and has been shown for both elevated exercise BP at moderate and maximal exercise [4].

With regard to cardiovascular outcome, in normotensive subjects, BelHT at intermediate exercise is particularly associated with an increased event rate [5], whereas BelHT at maximal exercise is less informative. Submaximal exercise better reflects everyday exercise intensities than maximal exercise, which is why high BP values at submaximal exercise are often associated (in up to 56%) with increased BP values in everyday life [6] (masked HT). In patients with established HT, the prognostic significance of BelHT is markedly attenuated, but that of increased TPR under stress is clearly present [7]. One possible reason could be that in some hypertensive patients with normal BP behavior under stress, a reduction in HZV due to left ventricular hypertrophy prevents the buildup of BelHT despite increased TPR and thus significantly reduces the prognosis of this patient group (Table 1).

Prognostic significance in patients with coronary artery disease: Myocardial ischemia under stress leads to impaired left ventricular pump function and thus to a reduction of HRV with prevention of BelHT, even in the presence of increased TPR (pseudo-normal BP response, tab. 1). The extreme example of this response is exercise hypotension (BP drop under stress) resp. the lack of BD increase. Therefore, it is not surprising that patients with BelHT show less frequent ischemia both angiographically and functionally and have a better prognosis than patients without BelHT [8]. However, these study data are relatively old, and the prognostic significance of BelHT in patients with coronary artery disease in the era of revascularization is ultimately not fully understood.

Management of exercise-induced hypertension: masked HT is common in patients with BelHT and should be sought by 24-h BP measurement when normotensive resting BP values objectify BelHT (Fig. 2) [9]. Important in the treatment of isolated BelHT are consistently implemented lifestyle measures, in particular regular physical activity, which, in addition to a BP reduction, can lead to weight reduction and improvement of the metabolic profile and increase the prognostically important physical fitness. Whether drug therapy of BelHT in normal resting BP is beneficial is controversial [3], as there are no outcome studies on this yet and as BelHT even appears prognostically favorable in patients with coronary artery disease. Therefore, pharmacotherapy of isolated BelHT should be used only in rare, individual cases, e.g., in frequent athletes with a dilated aorta. It has been shown that in patients with diastolic dysfunction and BelHT, administration of losartan lowers exercise BP and performance improves modestly, whereas hydrochlorothiazide lowers exercise BP but does not improve performance [10]. A BP-lowering effect during exercise has also been described for beta-blockers. They lead to a decrease in HZV, whereas TPR increases during the course of treatment. However, considering that adequate TPR reduction under stress has a crucial prognostic significance in patients with HT [7], beta-blockers may lead to a reduction in exercise capacity, and central BP is less favorably affected by beta-blockers, beta-blockers should not be used as first-line therapy for BelHT.

Sports in patients with arterial hypertension resp. Exercise Hypertension

The occurrence of survived myocardial infarction or even sudden cardiac death has been associated in part with vigorous exercise. The dreaded coronary events are due to rupture of a vulnerable coronary plaque and increasingly affect even younger athletes aged 25 years and older. The extent to which inadequate BP behavior plays a role in coronary plaque rupture is unclear.

BelHT and mild HT are by no means reasons to discourage regular aerobic activity, as there is undoubtedly a great benefit in engaging in regular aerobic physical activity in terms of prognosis. The BP-lowering effects of endurance exercise are particularly effective in patients with elevated BP and are approximately 5 mmHg. In patients with HT grade 2 , no high static physical activities should be performed until BP is controlled (Table 2) [11]. This is especially true in the presence of HT-related end-organ damage, such as hypertensive heart disease with dilatation of the aorta [12]. An argument for echocardiographic evaluation of athletes, especially in older, so-called master athletes or in athletes with suspected HT, is the detection of possible dilatation of the ascending aorta. Dilatation of the aortic sinus portion in athletes is unusual and should by no means be interpreted as a physiological development in the context of a “sports heart” [12]. If an unfavorable training behavior or lack of therapy is maintained, progression of dilatation with the risk of fatal dissection may occur in the course [12].

Hypertension in athletes

HT is the most common cardiovascular abnormality in screening examinations of primarily older athletes, but one also finds a not insignificant proportion of masked HT [13] in athletes with normal practice blood pressure values with elevated mean 24-h BP values. Especially in athletes with elevated BP, the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or other pressor substances (“energy drinks”, stimulants) should be actively questioned and avoided. Hypertensive athletes should receive echocardiography [10], and recommendations for sports fitness in athletes with HT are summarized in Table 2. The indication for therapy of HT is basically no different from that in non-athletes. In athletes, diuretics and beta-blockers should not be used as first-line therapy because they can reduce performance and cause electrolyte/fluid shifts. Moreover, these substances are included on the doping list and, in the case of diuretics, are prohibited in all sports and at all times. Therefore, the primary options for athletes are ACE inhibitors/ATII antagonists and calcium channel blockers [11].

Take-Home Messages

- Exercise-induced hypertension is inconsistently defined. A guideline is >210 mmHg systolic for men and >190 mmHg systolic for women under max. Stress with concomitant increase in diastolic blood pressure.

- The prognostic significance of exercise-induced hypertension in normotensive resp. prehypertensive healthy individuals with regard to the development of arterial hypertension is clearly given.

- In patients with exercise-induced hypertension and normotensive blood pressure values at rest, masked hypertension should be sought by 24-hour blood pressure measurement.

- Mild arterial hypertension or exercise-induced hypertension is not a reason to discourage aerobic exercise. In moderate to severe hypertension, exercise with a high static component should be avoided until arterial hypertension is well controlled.

- Arterial hypertension, not infrequently masked, occasionally occurs in competitive athletes and should be sought and appropriately evaluated.

Literature:

- Sharman JE, LaGerche A: Exercise blood pressure: clinical relevance and correct measurement. J Hum Hypertens 2015; 29(6): 351-358.

- Schultz MG, Sharman JE: Exercise Hypertension. Pulse 2014; 1(3-4): 161-176.

- Kim D, Ha JW: Hypertensive response to exercise: mechanisms and clinical implication. Clin Hypertens 2016; 22: 17.

- Schultz MG, et al: Clinical Relevance of Exaggerated Exercise Blood Pressure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 66(16): 1843-1845.

- Schultz MG, et al: Exercise-induced hypertension, cardiovascular events, and mortality in patients undergoing exercise stress testing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens 2013; 26(3): 357-366.

- Schultz MG, et al: Masked hypertension is “unmasked” by low-intensity exercise blood pressure. Blood Press 2011; 20(5): 284-289.

- Fagard RH, et al: Prognostic value of invasive hemodynamic measurements at rest and during exercise in hypertensive men. Hypertension 1996; 28(1): 31-36.

- Lauer MS, et al: Angiographic and prognostic implications of an exaggerated exercise systolic blood pressure response and rest systolic blood pressure in adults undergoing evaluation for suspected coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995; 26: 1630-1636.

- Brenner R, Allemann Y: [Exercise testing and blood pressure]. Praxis (Bern 1994) 2011; 100(17): 1041-1049.

- Little WC, et al: Effect of losartan and hydrochlorothiazide on exercise tolerance in exertional hypertension and left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Am J Cardiol 2006; 98(3): 383-385.

- Black HR, et al: Eligibility and disqualification recommendations for competitive athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities: task force 6: Hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. Circulation 2015; 132(22): e298-302.

- Pelliccia A, et al: Prevalence and clinical significance of aortic root dilation in highly trained competitive athletes. Circulation 2010; 122(7): 698-706, 3 p following 706.

- Trachsel LD, et al: Masked hypertension and cardiac remodeling in middle-aged endurance athletes. J Hypertens 2015; 33(6): 1276-1283.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(6): 28-32