Elevated uric acid in the blood can manifest as gout. Hyperuricemia is also being studied as an independent cardiorenal risk factor. At the Zurich Cardiology Review, the evidence situation was discussed.

“When we think of hyperuricemia, we reflexively think of gout. That is, of course, correct. However, we may be overlooking some other effects associated with the increase in uric acid levels in the blood,” says PD Bernhard Hess, MD, internist and nephrologist, Im Park Clinic, Zurich. There is ample evidence that hyperuricemia is also a cardiorenal risk factor (in its own right).

Epidemiologic data from 3329 Framingham Study participants (55.6% female), all without hypertension, history of myocardial infarction, heart/renal failure, or gout, showed a 17% increase in risk (OR 1.17; 95% CI 1.02-1.33) for newly developed hypertension and of 11% for further blood pressure progression for every 1 standard deviation increase in serum uric acid level [1]. This in a multivariate corrected analysis for age, sex, BMI, diabetes, tobacco/alcohol use, serum creatinine, proteinuria, GFR, and baseline blood pressure.

In addition, a 2011 meta-analysis using 18 prospective cohort studies with a total of 55 607 subjects in the endpoint of new-onset hypertension concluded that women with hyperuricemia tended to fare worse than men in terms of risk (76- vs. 38-percent increase) [2].

Hyperuricemia and endothelial dysfunction.

In prehypertensives (SBD 120-140 mmHg or DBD 80-90 mmHg), elevated serum uric acid levels appear to be associated with microalbuminuria (indicator of endothelial dysfunction) independent of other factors: Among 6771 subjects without diabetes or full-blown hypertension, Lee et al. [3] in the group of prehypertensives in the highest uric acid quartile a more than twofold increase in risk for microalbuminuria compared with the lowest quartile. The OR was 2.12 for men and 3.36 for women. This while controlling for other cardiovascular risk factors such as age, BMI, tobacco use, serum glucose, LDL/HDL cholesterol, CRP, fibrinogen, and GFR. In normotensives (<120 mmHg), the association was not evident.

What happens under therapy?

“Conversely, allopurinol therapy should thus have a positive effect on the aforementioned cardiovascular risk factors,” the speaker added. And indeed, there is evidence from small studies (so far) that this is so.

Thus, Feig et al. [4] in 2008 in newly diagnosed stage 1 hypertensives with serum uric acid concentrations of ≥356 µmol/l showed a significant reduction in blood pressure with allopurinol therapy compared with placebo. The dose administered was 2× 200 mg/d allopurinol for four weeks. The study had been carefully controlled and blinded.

Chronic kidney disease patients (stage 3) with left ventricular hypertrophy benefit significantly from the same agent (given at a dose of 300 mg/d for nine months and in addition to other drugs) in terms of endothelial function (p=0.009) and left ventricular hypertrophy (p=0.036) – each compared to placebo. These were the results of another randomized controlled trial with a small sample [5]. Again, it was ensured that other factors that might influence LVMI, for example, did not affect the result.

A large multicenter randomized trial on the topic is currently underway, with results expected in a few years (ALL-HEART) [6]. To examine the cardiovascular outcomes of allopurinol addition (up to 600 mg/d, in addition to standard therapy) in patients aged 60 years or older with ischemic heart disease.

Renal risk

In light of the foregoing, it is not surprising that a relationship between hyperuricemia and new-onset chronic kidney disease (CKD) can also be found. Epidemiologic data from Vienna on more than 20,000 healthy participants in a health screening program that lasted seven years and included 73,015 follow-up examinations revealed an almost twofold risk of new-onset CKD (stage 3 or eGFR <60) at slightly elevated uric acid levels of 416-529 µmol/l and a threefold risk at even higher levels of at least 530 µmol/l [7]. Even after controlling for other factors such as baseline eGFR, sex, age, antihypertensive therapy, and components of metabolic syndrome, the risk increase remained significant compared with the group without hyperuricemia. According to models of the same study, the increase was initially linear with increasing uric acid level – but from values (µmol/l) of 356-416 in women and 416-475 in men, the associated risk curve then steepened significantly. The observed adverse effects of serum uric acid on the kidney were again more pronounced in prehypertensives, hypertensives, and women.

Nephroprotection by allopurinol?

In a prospective randomized study of 113 patients with kidney disease (eGFR <60 ml/min), Goicoechea et al. [8] the benefit of allopurinol therapy on CKD. Can the drug slow disease progression even at a low dose of 100 mg/d?

It turned out that not only serum uric acid levels were significantly lower after two years of allopurinol treatment than in the group with standard therapy. Indeed, allopurinol administration also had beneficial effects on CKD independent of age, sex, diabetes, CRP, albuminuria, and blockade of the renin-angiotensin system. Renal disease progression slowed significantly. In the control group with standard therapy, eGFR decreased by 3.3 ml/min after two years, while in the study group it increased by 1.3 ml/min (p=0.018).

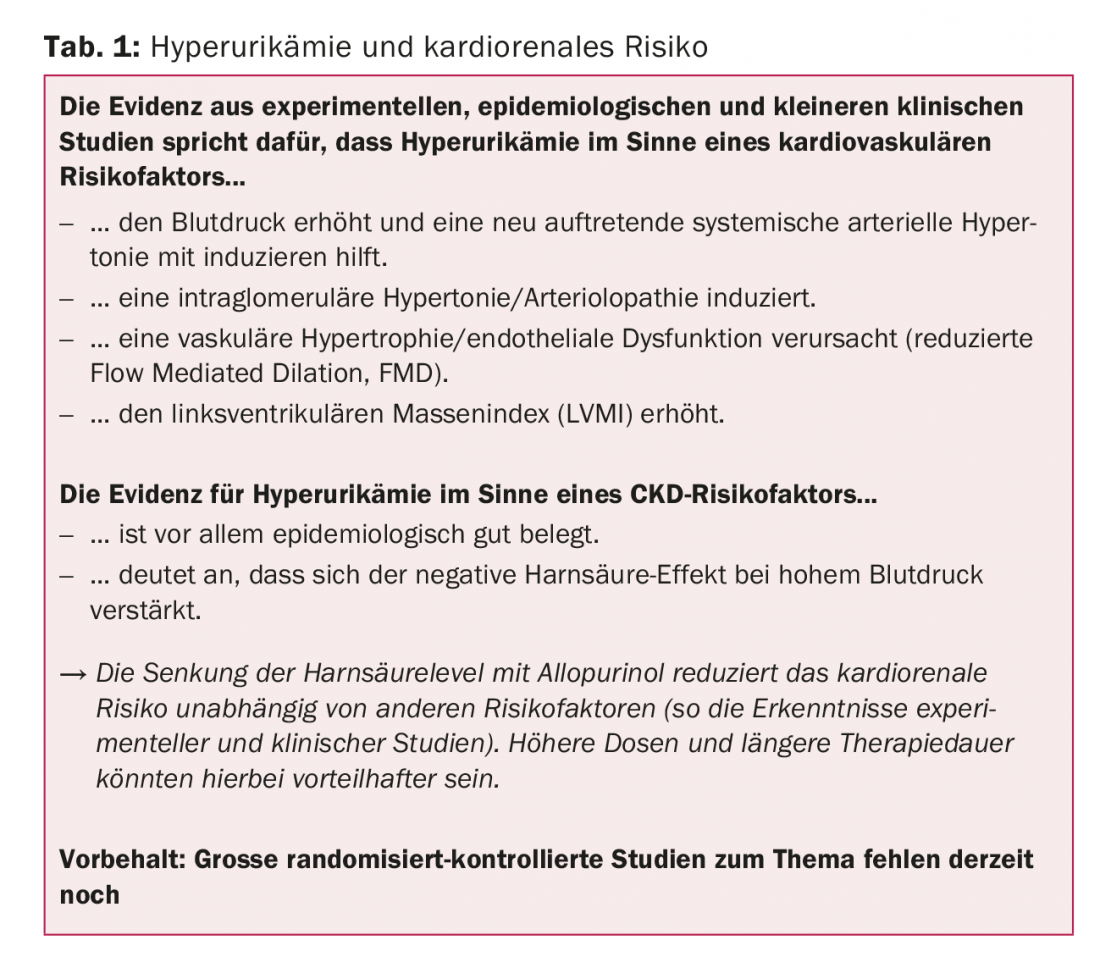

A retrospective cohort study from the USA [9] – “field evidence” as the speaker called it – with over 30,000 allopurinol treatments in elderly patients without previous renal insufficiency suggested a classic dose-response relationship when including several variables (including drug intake): Patients with a dose of at least 300 mg/d benefited most. They experienced a significant risk reduction of 29% with respect to new-onset renal failure compared with the 1-199 mg/d dose group. The same was true for longer duration of use: the longer, the lower the risk – with more than two years of therapy, the hazard ratio was 0.81 (0.67-0.98) compared with therapy of up to half a year. Allopurinol ≥300 mg/d was also associated with a significantly lower risk of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Table 1 summarizes the findings on hyperuricemia and cardiorenal risk.

Source: 15th Zurich Review Course in Clinical Cardiology, April 6-8, 2017, Zurich.

Literature:

- Sundström J, et al: Relations of serum uric acid to longitudinal blood pressure tracking and hypertension incidence. Hypertension 2005 Jan; 45(1): 28-33.

- Grayson PC, et al: Hyperuricemia and incident hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011 Jan; 63(1): 102-110.

- Lee JE, et al: Serum uric acid is associated with microalbuminuria in prehypertension. Hypertension 2006 May; 47(5): 962-967.

- Feig DI, Soletsky B, Johnson RJ: Effect of allopurinol on blood pressure of adolescents with newly diagnosed essential hypertension: a randomized trial. JAMA 2008 Aug 27; 300(8): 924-932.

- Kao MP, et al: Allopurinol benefits left ventricular mass and endothelial dysfunction in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011 Jul; 22(7): 1382-1389.

- Mackenzie IS, et al: Multicentre, prospective, randomised, open-label, blinded end-point trial of the efficacy of allopurinol therapy in improving cardiovascular outcomes in patients with ischaemic heart disease: protocol of the ALL-HEART study. BMJ Open 2016 Sep 8; 6(9): e013774.

- Obermayr RP, et al: Elevated uric acid increases the risk for kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008 Dec; 19(12): 2407-2413.

- Goicoechea M, et al: Effect of allopurinol in chronic kidney disease progression and cardiovascular risk. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010 Aug; 5(8): 1388-1393.

- Singh JA, Yu S: Are allopurinol dose and duration of use nephroprotective in the elderly? A Medicare claims study of allopurinol use and incident renal failure. Ann Rheum Dis 2017 Jan; 76(1): 133-139.

CARDIOVASC 2017; 16(3): 29-31