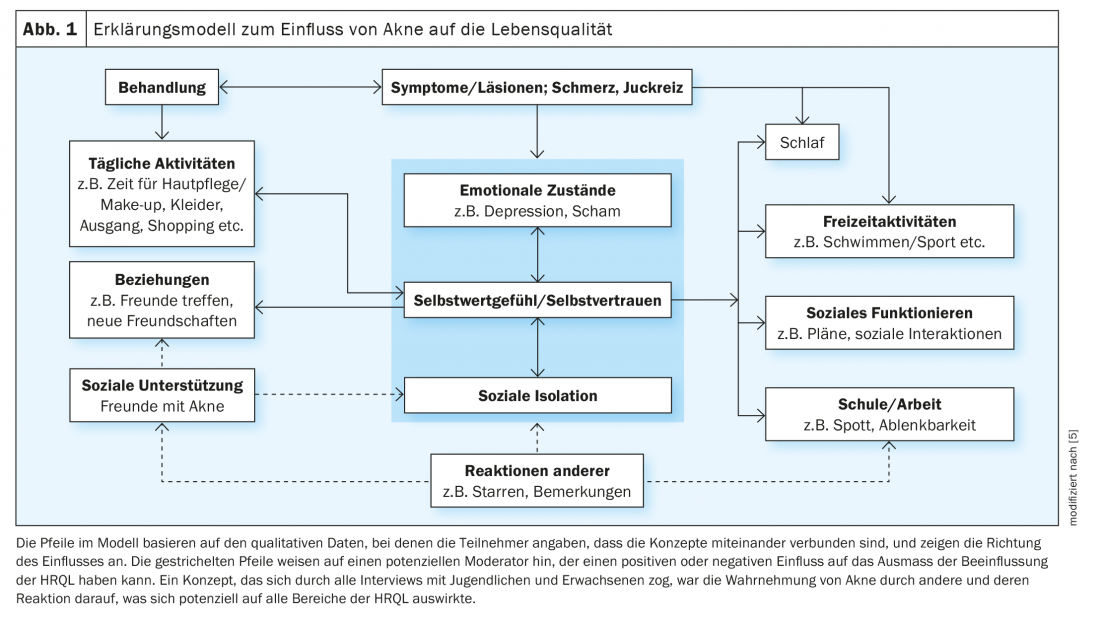

A survey study published in the journal Dermatology and Therapy examined the impact of moderate and severe acne on health-related quality of life in adolescent and adult patients. Based on the results, the study authors designed an explanatory model that illustrates corresponding correlations and shows how the treatment of acne patients can be optimized by taking psychosocial aspects into account.

According to scientific research, about 30-50% of acne patients aged 12-20 years suffer from psychological comorbidities such as anxiety, depression and social anxiety [1–3]. Other psychosocial effects such as decreased self-esteem, frustration, and anger have also been observed [4]. Patients with adult acne are also more likely to develop anxiety and depressive disorders than the general population [5,6]. Last but not least, since these factors may also have an impact on treatment adherence, clinicians should pay attention to corresponding symptoms. Currently, there are numerous treatment options for acne. Guidelines recommend a combination of a topical retinoid and an active substance with antimicrobial properties for most patients to treat both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions [7]. Although acne usually requires prolonged treatment, one large study found insufficient treatment adherence in half of the participants [15]. This is an influenceable factor that is important for therapy outcomes. One review concluded that effective relief of acne is associated with improvement in sufferers’ self-assessment, underscoring the potential benefits of effective acne treatment on health-related quality of life [13].

Design of the qualitative study

To find out more about the associations between acne and health-related quality of life, Fabbrocini et al. conducted a survey study. Adolescents (12-17 yr) and adults (≥18 yr) were included. Y.) who were diagnosed with acne vulgaris and had facial lesions, including papules and/or pustules [5]. Another inclusion criterion was current or prescribed topical acne therapy during the past 6 months. The semi-structured interview guide included open-ended questions that allowed participants to spontaneously describe how acne affects them, e.g., “What is the most difficult thing about having acne?” followed by open-ended questions on different domains of health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Specific questions were also asked, such as “How does acne affect your self-confidence or self-esteem?” Also asked were participants’ experiences with topical acne treatment and their views on various aspects of topical therapy.

A total of 34 adolescents and 16 adults with moderate to severe acne participated. The study participants were from the UK, Italy and Germany. The average age of the adolescent subjects was 15 years and of the adult subjects 28 years. Interview transcripts were systematically coded using the qualitative software tool MAXQDA [5,8].

Based on the analyzed data, an explanatory model was developed to illustrate the effects of acne on HRQoL and the links between concepts (Fig. 1) [5]. Emotional states appear to impact all other areas of HRQoL.

Stigma correlates HRQoL

The results of the present study support the many other scientific studies demonstrating the negative effects of acne on HRQoL [9–11]. For example, a previously conducted analysis found that among adults with acne, perceived stigma was a significant predictor of acne-related HRQoL – more significant than factors such as severity, gender, or age [12]. The results of the current study support this; the negative impact of feeling judged for their acne or feeling stared at by other people because of skin lesions was mentioned by most participants. And although many subjects had social media accounts, they did not post pictures of themselves when they had visible acne lesions and, moreover, avoided having their picture taken.

Differences between adolescent and adult acne patients

Although the effects of acne on adolescents and adults are similar, there are some important differences. In adolescents, acne is more common among peers; therefore, many adolescents had friends or colleagues in their circle of acquaintances who were also affected by acne, so they had some social support from ‘fellow sufferers’. Among adults, some reported not knowing anyone their own age who also suffered from acne, resulting in feelings of loneliness and not being understood. Adult sufferers reported that most people think of acne as something that only affects teenagers. This error sometimes leads to the misconception that the skin lesions are due to improper skin care, malnutrition or other skin diseases.

What do patients expect from acne therapy?

A difference between male and female participants was evident in the use of makeup to hide acne [13,14]. In contrast to the female participants, only a small proportion of the male subjects had attempted to conceal their acne with cosmetics. The study also examined, among other things, the importance of various properties of topical acne therapies. For both adolescents and adults, the most important features were fast-acting treatments that do not cause irritation and do not contaminate clothing.

Literature:

- Golchai J, et al: Comparison of anxiety and depression in patients with acne vulgaris and healthy individuals. Indian J Dermatol 2010; 55: 352-354.

- Halvorsen JA, et al: Suicidal ideation, mental health problems, and social impairment are increased in adolescents with acne: a population-based study. J Invest Dermatol 2011; 131: 363-370.

- Henkel V, et al: Screening for depression in adult acne vulgaris patients: tools for the dermatologist. J Cosmet Dermatol 2002; 1: 202-207.

- Magin P, et al: Psychological sequelae of acne vulgaris: results of a qualitative study. Can Fam Physician 2006; 52: 978-979.

- Fabbrocini G, Cacciapuoti S, Monfrecola G: A Qualitative Investigation of the Impact of Acne on Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQL): Development of a Conceptual Model. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2018; 8: 85-99.

- Altunay IK, et al: Psychosocial Aspects of Adult Acne: Data from 13 European Countries. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020 Feb 5; 100(4):adv00051.

- Thiboutot D, et al: New insights into the management of acne: an update from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne group. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 60(5 Suppl):S1-5.

- Brown V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77-101.

- Klassen AF, Newton JN, Mallon E: Measuring quality of life in people referred for specialist care of acne: comparing generic and disease-specific measures. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 43(2 Pt 1): 229-233.

- Mallon E, et al: The quality of life in acne: a comparison with general medical conditions using generic questionnaires. Br J Dermatol 1999; 140(4): 672-676.

- Tasoula E, et al.: The impact of acne vulgaris on quality of life and psychic health in young adolescents in Greece. Results of a population survey. An Bras Dermatol. 2012; 87(6): 862-869.

- Liasides J, Apergi FS: Predictors of quality of life in adults with acne: the contribution of perceived stigma. EpSBS. 2015. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2015.01.17 (II:icCSBs).

- Araviiskaia E, Dreno B: The role of topical dermocosmetics in acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2016; 30(6): 926-935.

- Del Rosso JQ: The role of skin care as an integral component in the management of acne vulgaris: part 1: the importance of cleanser and moisturizer ingredients, design, and product selection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2013; 6(12): 19-27.

- Dreno B, et al: Large-scale worldwide observational study of adherence with acne therapy. Int J Dermatol 2010; 49(4): 448-56.

- Renzi C, et al: Factors associated with patient satisfaction with care among dermatological outpatients. Br J Dermatol 2001; 145(4): 617-623.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2022; 32(3): 24-25