Prevalence of peripheral arterial disease increases. 5-year mortality in asymptomatic and symptomatic PAVK is twice that in patients without PAVK. Screening and initial diagnosis possible with simple means. Drug treatment necessary. Drug treatment and gait training optimize cardiovascular risk factors. Low-invasive treatment options diverse and constantly expanding. Low-invasive treatment options also reasonable for elderly and polymorbid patients. Therapy planning preferably interdisciplinary. Select type of therapy adapted to the individual patient.

The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease increases significantly with increasing age of the population. It generally ranges around 3-10% and reaches 15-20% in >70-year-old people [1]. Today, maintaining mobility and quality of life are defined goals at any age. At the same time, the demand for the least invasive and most widely available therapies at a reasonable cost is growing. Symptoms of peripheral arterial disease massively limit the quality of life of active people. Critical limb ischemia threatens the limb and the patient’s life. In addition to conservative measures, such as drug therapy to optimize cardiovascular risk factors and antiaggregation, and gait training to promote collateral perfusion, we can offer interventional therapy in both situations. This ranges from minimally invasive, purely catheter-based intervention to combined surgical and catheter-based measures (so-called hybrid interventions) to vascular surgery such as open thromboendarterectomy and bypass. Subsequently, less invasive catheter-based and hybdrine interventions are discussed.

Significance of peripheral arterial disease

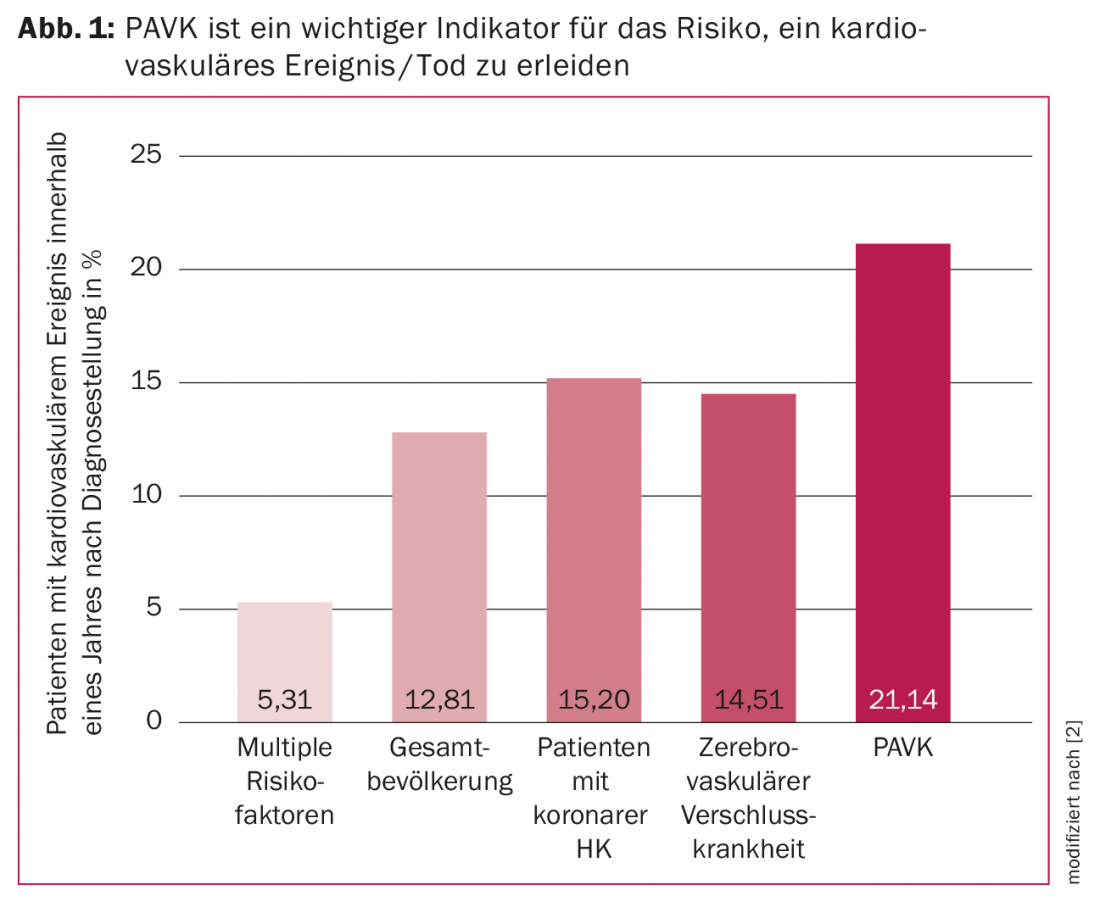

People with peripheral arterial disease have a higher risk of a cardiovascular ischemic event than patients with coronary or cerebrovascular occlusive disease [2]. The 5-year mortality risk is the same in asymptomatic and symptomatic PAVK patients and twice as high as in patients without PAVK [3].

Diagnosis of peripheral arterial occlusive disease in everyday practice

In addition to the typical anamnesis, such as Claudicatio intermittens arteriosa symptoms, examination methods available in clinical routine, such as auscultation, pulse palpation and ankle artery pressure measurement with ankle-brachial index calculation (“Ankle Brachial Index” [ABI]) are helpful to recognize a part of the patients without additional technical examinations and to lead them to further clarifications.

Treatment options for peripheral arterial disease

Conservative measures should be presented to the patient as an indispensable part of therapy. Drug therapy to optimize cardiovascular risk factors and antiaggregation, as well as gait training, influence cardiovascular prognosis. The reduction in quality of life due to intermittent claudicationis significant, especially for active people. The pain-related reduction in the extent of movement influences not only the physical but also the mental well-being. The less invasive therapeutic measures available today should also be applied sensibly in elderly and polymorbid patients. They are very often possible without general anesthesia under local, or in the case of combined surgical-catheter procedures, under locoregional anesthesia.

The complication rate (puncture site hemorrhage, aneurysm spurium or arterio-arterial embolism, or thrombotic early occlusion) is low in skilled hands and often manageable by catheterization.

Technical procedure and type of pathological vascular finding

Catheter-based intervention options are growing with increasing experience and innovation in thought and materials. Arterial access is usually chosen inguinally via the femoral artery. Here, depending on the treatment plan, antegrade (toward the leg arteries) or retrograde (toward the iliac arteries) ipsilateral or crossover from one side to the opposite side via the aortic bifurcation may be used. Brute force approaches are also possible. In addition, if necessary for occlusion revascularization in the area of the leg arteries for retrograde wire passage, also crural distal, or in the area of the foot arteries are punctured.

Today, in addition to coronaries and vessels supplying the brain, arteries of the upper and lower extremities down to the foot – aorta as well as its branches such as mesenteric and renal arteries – are treated using catheter technology.

Indications include treatment of circumscribed stenoses up to revascularization of fresh embolic, but also fresh thrombotic occlusions; or older to chronic occlusions, partly up to the foot arteries (in case of non-healing lesions), either unilaterally (also bilaterally in the same procedure), either via the same femoral access crossover or in case of findings in the aortic bifurcation also bifemorally at the same time (so-called kissing balloon or kissing stent technique).

Technical requirements

Most catheter arterial procedures are performed under angiographic imaging (ionizing radiation) with iodinated contrast medium or, in cases of severely impaired renal function, withCO2. This requires an angiography-capable X-ray capability, which can range from the appropriate C-arm to compact systems to a hybdrid surgery suite. Arterial puncture can also be performed under sonography control. Circumscribed interventions would be purely sonography-guided, with the disadvantage of the corresponding time expenditure and the lack of angiographic documentation of findings.

Cathertechnical material and technical basics

For percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA), we need arterial access, which is created by percutaneous arterial puncture via a guidewire and sheath insertion (thick-lumen short catheter with check valve) using seldinger technique. The guide wire is advanced under visualization over the lesion to be treated and placed in the healthy distal vascular lumen. The catheter material can be advanced over this. We use uncoated balloon dilatation catheters, paclitaxel drug-eluting balloons (“Drug Eluting Balloon” [DEB]), stents made of medical stainless steel (so-called “bare metal stents”) of different alloys such as cobalt-chromium, cobalt-nickel or platinum-chromium, or drug-eluting stents (so called “stents”). “Drug Eluting Stents” [DES] with everolism or paclitaxel) [4,5]. Material development is constantly trying to reduce the restenosis and reclosure rate. The use of drug-eluting balloons significantly reduced the restenosis rate. The use of so-called bioresorbable stents would be very tempting. However, the data for peripheral arteries are still of insufficient evidence to make recommendations [6]. Also used are stents with PTFE covering mainly in the treatment of aneurysms, AV fistulas, iatrogenic perforations. Depending on the type of procedure, thrombectomy and atherectomy catheters and specialized re-entry devices are available. The further development of materials is constantly opening up new fields of treatment.

Catheter technical interventions – indication and examples

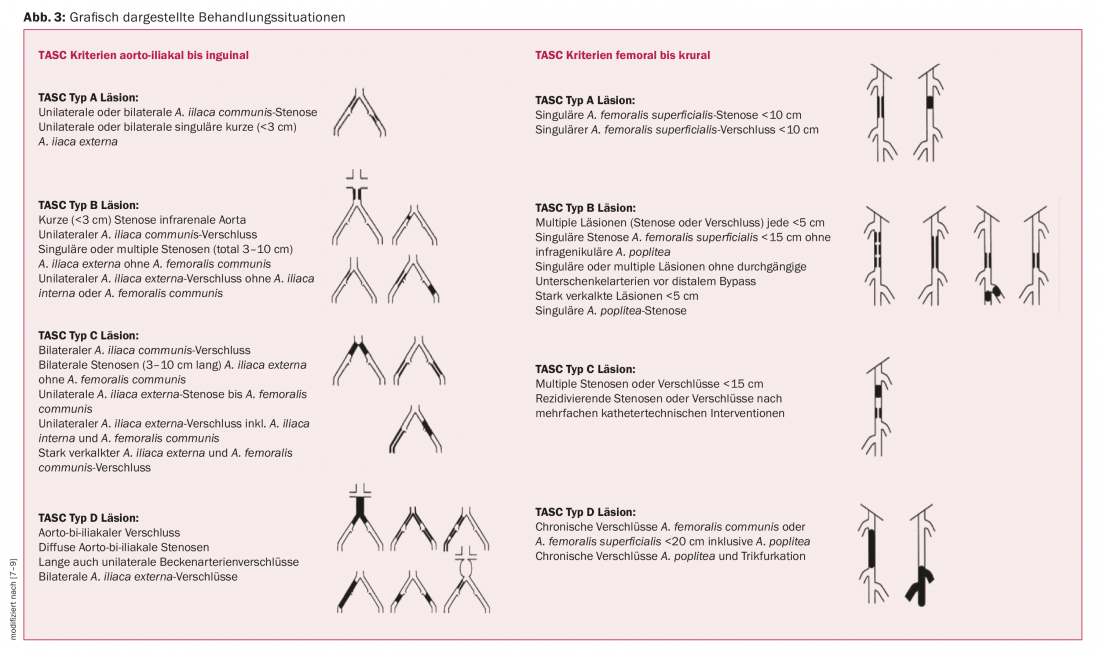

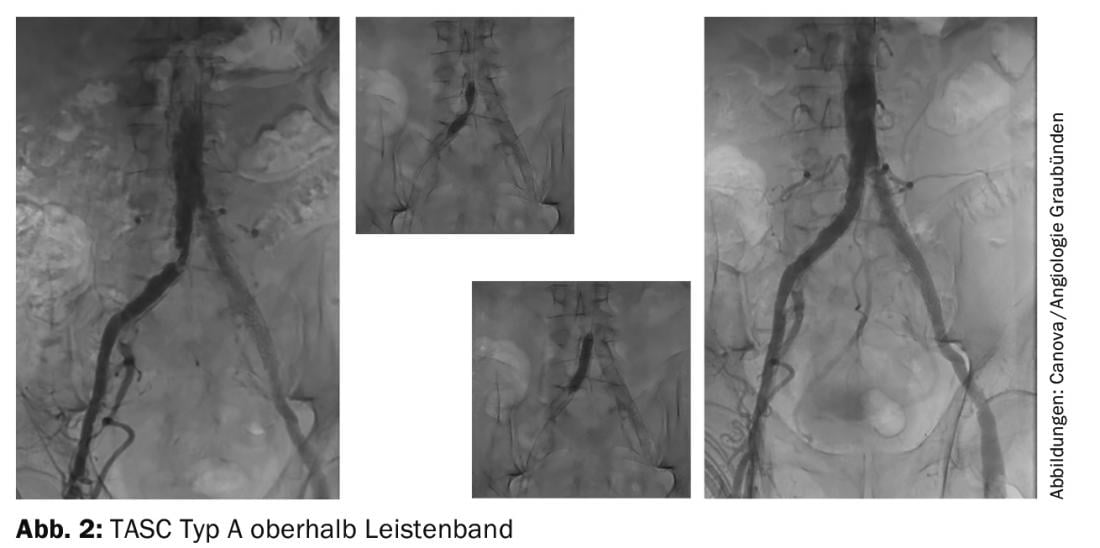

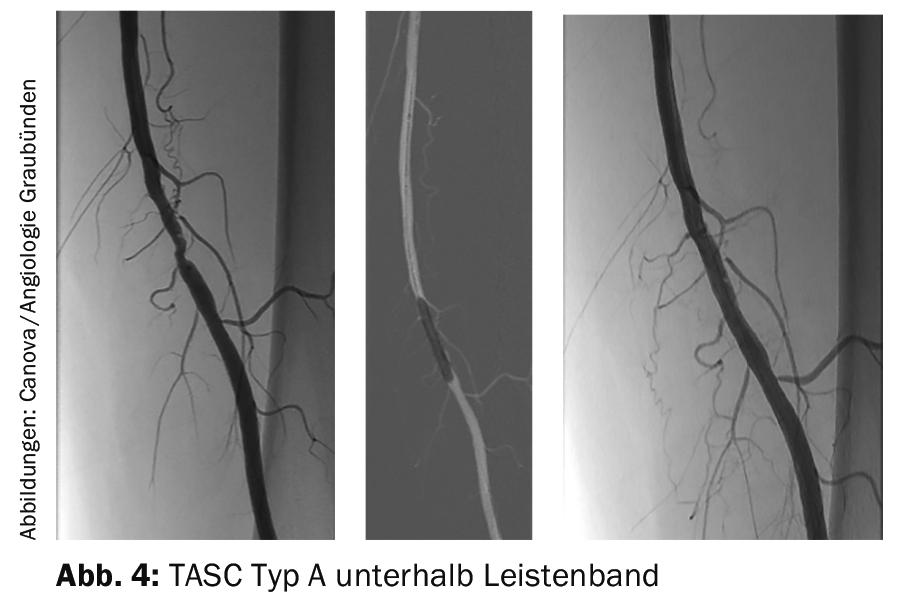

The indication and selection of interventional treatment is based on evidence-based recommendations and should be patient-adapted in interdisciplinary discussions involving vascular physicians of different specialties (e.g., surgeons, radiologists, angiologists). Recommendations for the choice of therapy can be found in the TASC document (“Trans Atlantic Inter-Society Consensus”). [7–9]Depending on the location (aortic, iliac, femoral to crural) and type of lesion (unilateral or bilateral, short- or long-stretch, involving the aortic bifurcation and distance from the renal arteries or involving the A. femoralis communis) and depending on the acuity (fresh embolic or thrombotic or chronic calcified) pure catheter percutaneous, combined surgical catheter or pure surgical is preferred. The move toward catheter-based procedures is also evident here, with TASC recommendations mentioning endovascular procedures in three of four types, especially when the surgical risk is judged to be not low. Purely endovascular treatment is used for unilateral circumscribed findings (TASC type A) above or below the inguinal ligament (Figs. 2 and 4) .

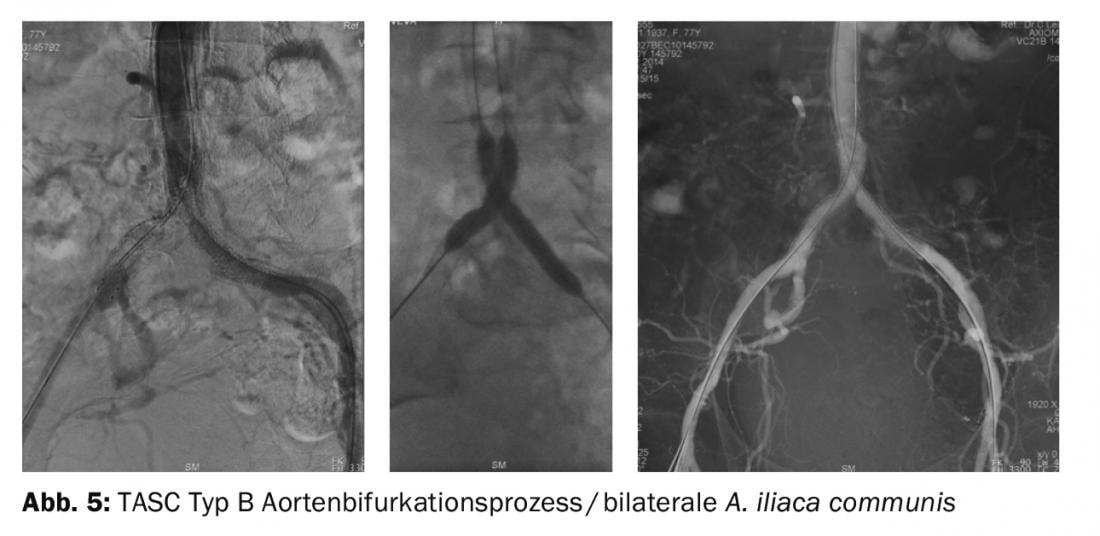

Rather endovascular treatment is used for circumscribed findings in the aorta and iliaco-femoral junction without the common femoral ar tery (TASC type B). Endovascularly recommended especially when the surgical risk is not low are aortic bifurcation processes/bilateral common iliacartery occlusions (Fig. 5) and severely calcified distal iliac arteries (external iliac artery ) or inguinal artery obstructions (TASC type C). Purely surgical recommendations include long-stretch iliac artery occlusions, aortic and iliac artery occlusions, and chronic inguinal artery (common femoral artery) and long-stretch (>20 cm) femoral artery occlusions involving the popliteal artery (TASC type D) (Fig. 6).

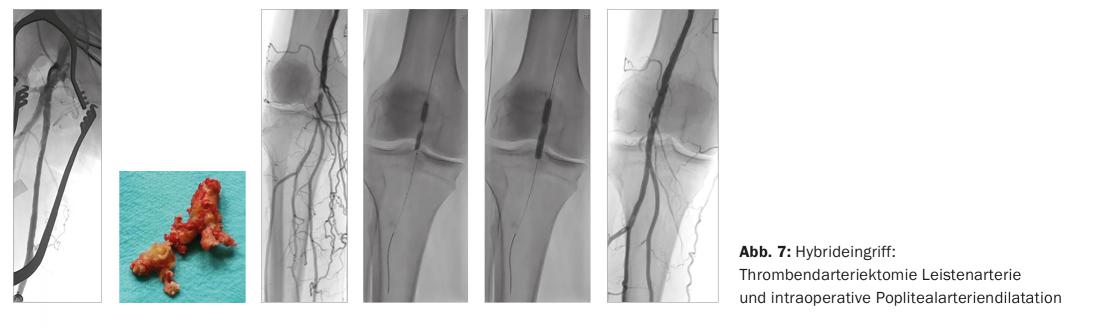

We perform so-called hybrid procedures for massively calcified femoral bifurcation with open thromboendarterectomy with plastic patch dilation and intraoperative balloon dilatation retrograde iliac or antegrade ( Fig. 7).

Conclusion

Peripheral arterial disease should be recognized and treated. Low-invasive catheter-based treatment options are constantly evolving. The choice of therapy (purely endovascular – combined as a so-called hybrid intervention – purely surgical) should be made interdisciplinary in knowledge of the application possibilities of current techniques, tailored to the individual patient and taking into account his risks and wishes.

Literature:

- Dua A, et al: Epidemiology of Peripheral Arterial Disease and Critical Limb Ischemia. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol 2016; 19(2): 91-95.

- Coen DA, et al. for the EFIM Vascular Medicine Working Group: Peripheral arterial disease: A growing problem for the internist. European Journal of Internal Medicine 2009; 20(2): 132-138.

- Meves SH, et al. for the getABI Study Group: Excess cardiovascular mortality in patients with peripheral arterial disease in primary care: 5-year results of the getABI study. Cerebrovasc Dis 2010; 29(6): 546-554.

- Jongsma H, et al: Drug-eluting balloon angioplasty versus uncoated balloon angioplasty in patients with femoropopliteal arterial occlusive disease. J Vasc Surg 2016 (July 29). doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.05.084. [Epub ahead of print 2016 July 29]

- Stoner MC, et al. on behalf of the Society for Vascular Surgery: Reporting standards of the Society for Vascular Surgery for endovascular treatment of chronic lower extremity peripheral artery disease. J Vasc Surg 2016; 64(1): e1-e21.

- van Haelst ST, et al: Current status and future perspectives of bioresorbable stents in peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg 2016 (July 26). doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.05.044. [Epub ahead of print 2016 July 26]

- Norgren L, et al. for the TASC II Working Group: TASC II section F on revascularization in PAD. J Endovasc Ther 2007; 14(5): 743-744.

- Jaff MR, et al. for the TASC Steering Committee: An Update in Methods for Revascuralisation and Expansion of the TSAC Lesion Classification to include Below-the-Knee Arteries: A. Supplement to the Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II): Endovasc Ther 2015; 22(5): 663-677. doi: 10.1177/1526602815592206. [Epub ahead of print 2015 Aug 3]

- Starodubtsev V, et al: Hybrid and open surgery of Trans Atlantic Inter Society II Type C and D iliac occlusive disease and clinical lesion of common femoral artery. Int Angiol 2016; 35(5): 484-491. [Epub ahead of print 2015 Nov 10]

CARDIOVASC 2016; 15(5): 18-22