Cognitive impairment is a key factor in patients’ quality of life and independence. How effective are currently approved drugs? And what is happening in the non-pharmacological field?

Many attempts to treat Cognitive Impairment (CI) in Parkinson’s disease are based on working with neurotransmitters. Dopamine is partly responsible for frontal brain syndrome, serotonin for depressive symptomatology. Norepinephrine is involved in limiting attention and impaired mood, and acetylcholine affects posterior cortex function.

Dopamine replacement therapy does not produce long-term cognitive improvement

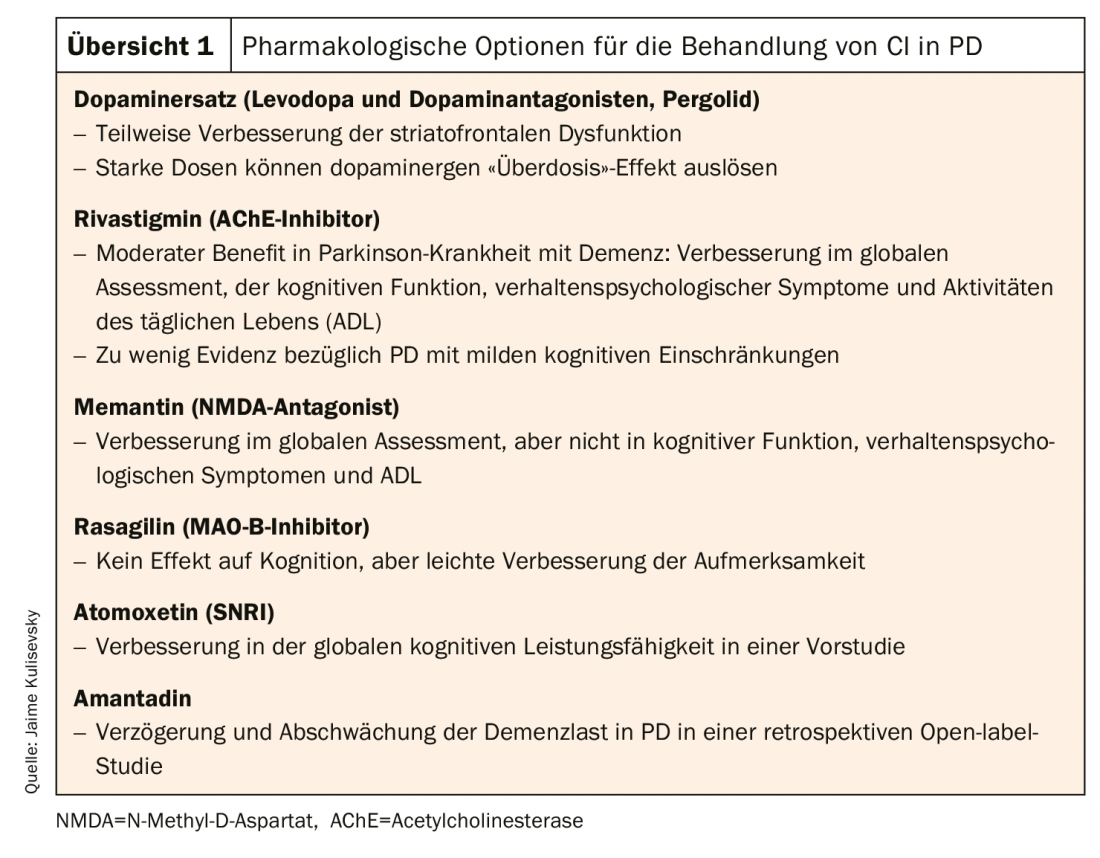

Impairment of executive functions due to a dopamine deficit significantly limits the independence of patients, as Jaime Kulisevsky, MD, PhD, from Sant Pau Hospital in Barcelona emphasizes at the beginning of his presentation. Because it affects sequencing and planning skills (necessary for managing finances, shopping, cooking, etc.), attention, short-term memory, and language skills. Dopaminergic replacement therapy led to significant short-term motor improvement in therapy-naive patients, although outcomes still remained below the normal range; cognitive deficits could not be adequately compensated. Long-term follow-up over two years also showed that – while motor improvement persisted – cognitive improvement declined after 18 months and was no longer significant at the end of the observation period [1]. Patients already treated with dopaminergic therapy differentiate stable responders, who show only minor cognitive improvements, and those who even experience an “overdose effect” with acute transient decline in performance on demanding tasks (consistent with high levodopa plasma levels) [2]. An “overdose effect” can be prevented with a slower increase in LD levels.

Rasagiline did not achieve statistical relevance in the placebo comparison in terms of cognitive improvement, but also did not lead to worsening. The agent improved motor functions and was also found to be well tolerated in elderly patients [3].

Cholinesterase inhibitors against cholinergic denervation.

Acetylcholine significantly influences cellular excitability and network synchronization in the neocortex and hippocampus, which has implications for attention, arousal, sensory processing, and memory. Extensive progressive cholinergic denervation occurs, which, although evident across the cognitive spectrum, is more common in PD patients with severe CI. This suggests a crucial role of cholinergic denervation processes in the development of dementia [4]. A meta-analysis of 10 large RCTs examining the use of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine to treat cognitive impairment in patients with Parkinson’s disease (CIND-PD), Parkinson’s disease with dementia (PDD), or Lewy body dementia (LBD) found that both interventions resulted in moderate improvement in overall condition. However, only the cholinesterase inhibitors such as rivastigmine showed an increase in cognition. [5]. A recent metastudy confirmed this result. Moreover, it showed that cholinesterase inhibitors had a significant effect on attention, information processing speed, executive functions, memory, and language, although they did not affect visuospatial cognition. Memantine also showed a significant effect on attention, information processing speed, and executive functions. An influence on the frequency of falls could not be determined. All agents tested, especially rivastigmine, resulted in increased side effects compared with placebo [6]. However, these results are not unequivocal: another study showed small positive trends with respect to the efficacy of rivastigmine in improving cognition, but

no real treatment effect [7].

Atomoxetine, from the selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) group, was not effective in treating depressive symptoms in a study of depression and neuropsychiatric symptoms in PD, but was associated with improvement in global cognitive performance (p=0.003) and daytime sleepiness (p=0.001) [8].

Train with computer games

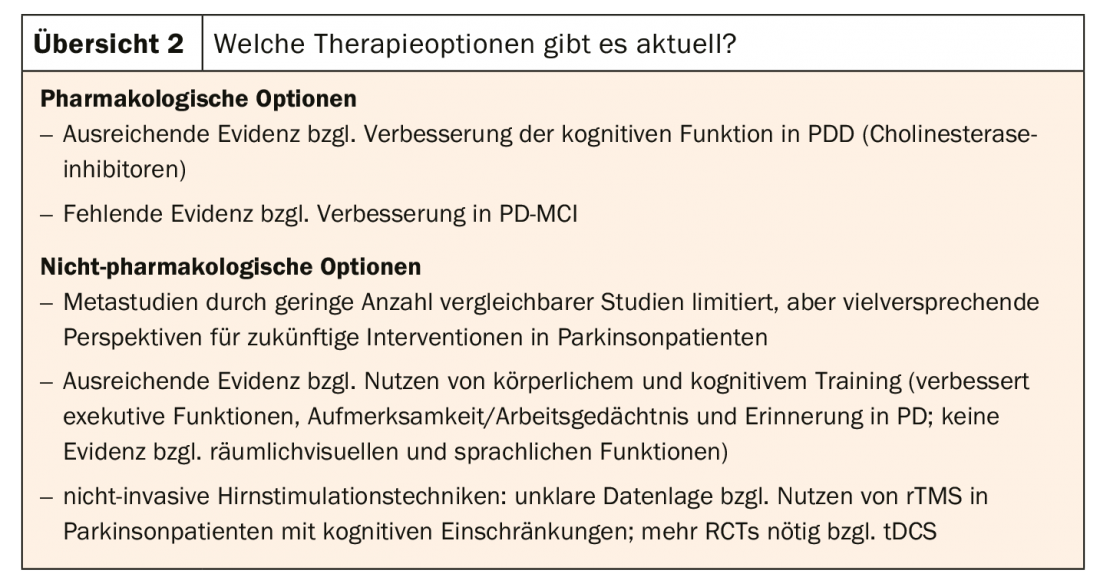

A few studies point to some benefit from cognitive training and other nonpharmacologic interventions. Thus, a study investigating the efficacy of integrative cognitive training (REHACOP) concluded the following: After three months, PD patients who received REHACOP showed significant and clinically relevant positive changes in information processing speed, visual memory, metacognition, and functional impairment compared with the control group. Based on these findings, the study authors call for integration of cognitive training into the care of PD patients [9].

The use of computer games as a training tool is controversially discussed. When comparing cognition-specific training and “motion controlled” computer games (sports games via Wii) in PD patients, one study showed that with regard to increasing cognitive performance, it makes no difference whether the training was specifically designed to promote cognition – or whether it is simply a computer game. After four weeks of training, patients using Wii were even slightly stronger in attention (95%, CI -1.49 to -0.11) than those using CogniPlus. The authors note that computer games are an equally valid and, at the same time, less expensive and arguably more entertaining training method [10]. However, further studies are needed to determine whether such training over time produces greater changes in attention, visuoconstructive (here the Wii group achieved near statistical relevance; p=0.05), and other cognitive abilities.

Cognitive training and non-invasive methods.

A recent review [11] confirms a significant effect of cognitive training on attention, executive functions, and information processing speed. However, it also notes that cognitive training had no visible effect on overall cognition. This may be due to the measuring instruments. “Future studies will look at whether our measurement techniques are appropriate,” says Kulisevsky, MD, “and whether individualized cognitive training is better than group training.” Because that, too, is still an open question.

Noninvasive brain stimulation also has a treatment effect on cognitive deficits in PD patients, a 2017 meta-analysis found. While this is not particularly large, it is at least significant. Pooled effect size (Hedges’ g) was measured. With regard to executive functions, there was a medium effect size (g=0.51), and for attention/working memory a small but also significant one (g=0.23). No significant pooled effect size was seen with rTMS (TMT-A and FAB). These findings are limited by the fact that only two of the 14 studies examined included participants with cognitive deficits [12].

In particular, combinations of cognitive training and noninvasive techniques may prove helpful, as one study demonstrated using transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Stimulation of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in combination with computer-based cognitive training showed a significant reduction in depressive symptoms as well as an improvement in word fluency [13].

Transcranial magnetic stimulation is considered a safe and effective way to influence mood. Their rapid therapeutic efficacy is comparable to that of antidepressants. However, there is a need for further study with regard to cognitive impairment in patients with Parkinson’s disease, although existing data suggest that it has no therapeutic effect, at least in patients with mild cognitive deficits. However, rTMS has an impressive placebo effect: 45% of those treated with rTMS reported minimal improvement, and 23% reported strong to very strong improvement [14].

Tip of the speaker: Tango!

Sport also has a beneficial effect. A sub-study of the PRET-PD trial found that exercise twice weekly for 24 months improved attention and working memory in non-demented patients with mild to moderate PD [15]. Aerobic exercise seems to have the most lasting effect. “You can also take tai chi or qigong. Both have a beneficial effect on motor skills, mood and quality of life,” says Kulisevsky, MD. However, the study situation regarding the influence on cognition is inconclusive. “I for one would recommend tango!” Because, according to the authors of a smaller study, Argentine tango promotes balance and functional mobility and even has a moderate effect on cognition as well as fatigue in Parkinson’s patients [16].

Target disease modification

“We urgently need studies focusing on cognition in Parkinson’s patients,” concludes Kulisevsky, MD. With the exception of rivastigmine, the currently approved drugs have only limited efficacy (overview 1) . Now that good measurement instruments are available, it is important to build up the study design very carefully. These include good patient selection (homogeneous groups, complementary samples), an adequate and standardized selection of instruments for cognitive screening, or measurement methods that can also be used in a multicenter setting. It is also important to use a functional instrument to determine the impact on the patient’s daily life.

While the literature on drug strategies is rather sparse, it is growing with respect to non-pharmacological approaches, which are promising overall (review 2).

“Future approaches will involve disease modification,” Kulisevsky, MD, says. She is the target. Therapies are needed that target pathological processes responsible for cognitive decline: α-synuclein deposits, Alzheimer pathologies (e.g., amyloid plaques), and inflammatory processes.

Source: EAN 2019, Oslo (NO)

Literature:

- Kulisevsky J, et al: Chronic effects of dopaminergic replacement on cognitive function in Parkinson’s disease: a two-year follow-up study of previously untreated patients. Mov Disord 2000; 15(4): 613-626.

- Kulisevsky J: Role of dopamine in learning and memory: implications for the treatment of cognitive dysfunction in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Drugs Aging 2000; 16(5): 365-379.

- Weintraub D, et al: Rasagiline for mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: A placebo-controlled trial. Mov Disord 2016; 31(5): 709-714.

- Bohnen NI, et al: Frequency of Cholinergic and Caudate Nucleus Dopaminergic Deficits Across the Predemented Cognitive Spectrum of Parkinson Disease and Evidence of Interaction Effects. JAMA Neurol 2015; 72(2): 194-200.

- Wang HF, et al: Efficacy and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease, Parkinson’s disease dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies: systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015; 86(2): 135-143.

- Meng YH, et al: Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for Parkinson’s disease dementia and Lewy body dementia: A meta-analysis. Exp Ther Med 2019; 17(3): 1611-1624.

- Mamikonyan E, et al: Rivastigmine for mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease: a placebo-controlled study. Mov Disord 2015; 30(7): 912-918.

- Weintraub D, et al: Atomoxetine for depression and other neuropsychiatric symptoms in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2010; 75(5): 448-455.

- Peña J, et al: Improving functional disability and cognition in Parkinson disease: randomized controlled trial. Neurology 2014; 83(23): 2167-2174.

- Zimmermann R, et al: Cognitive training in Parkinson disease: cognition-specific vs nonspecific computer training. Neurology 2014; 82(14): 1219-1226.

- Kampling H, Brendel LK, Mittag O: (Neuro)Psychological Interventions for Non-Motor Symptoms in the Treatment of Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: a Systematic Umbrella Review. Neuropsychol Rev 2019; 29(2): 166-180.

- Lawrence BJ, et al: Cognitive Training and Noninvasive Brain Stimulation for Cognition in Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-analysis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2017; 31(7): 597-608.

- Manenti R, et al: Transcranial direct current stimulation combined with cognitive training for the treatment of Parkinson Disease: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. Brain Stimul 2018; 11(6): 1251-1262.

- Randver R: Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex to alleviate depression and cognitive impairment associated with Parkinson’s disease: A review and clinical implications. J Neurol Sci 2018; 393: 88-99.

- David FJ, et al: Exercise improves cognition in Parkinson’s disease: The PRET-PD randomized, clinical trial. Mov Disord 2015; 30(12): 1657-1663.

- Romenets RS, et al: Tango for treatment of motor and non-motor manifestations in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized control study. Complement Ther Med 2015; 23(2): 175-184.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(5): 23-25 (published 8/26/19, ahead of print).