Pulmonary embolism (LE) is grouped together with deep vein thrombosis as venous thromboembolism. Whereas 50 years ago the diagnosis was usually made post-mortem or in the presence of definite clinical findings such as dyspnea, chest pain, or obstructive shock due to limited diagnostic capabilities, the spectrum of LE disease has changed in recent decades.

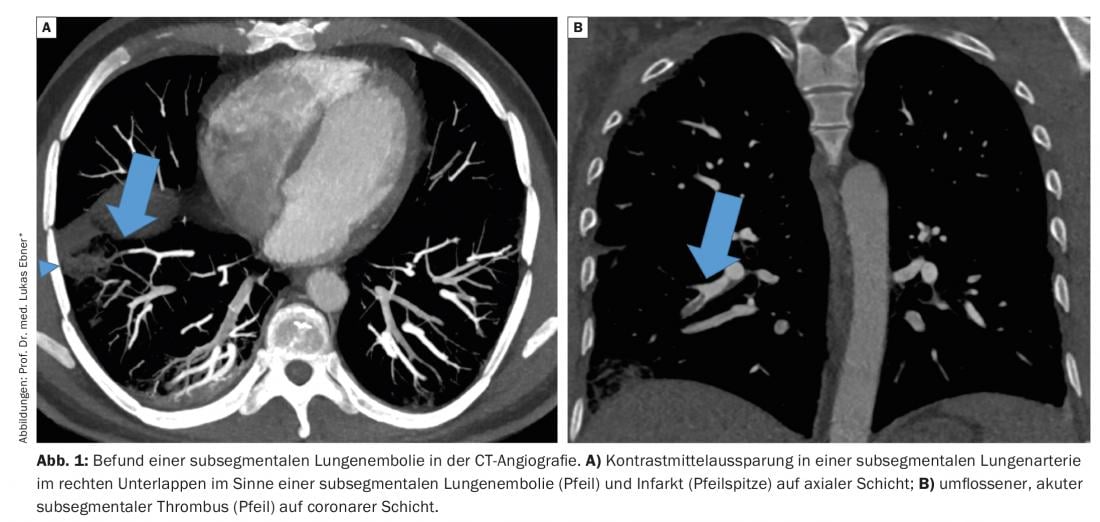

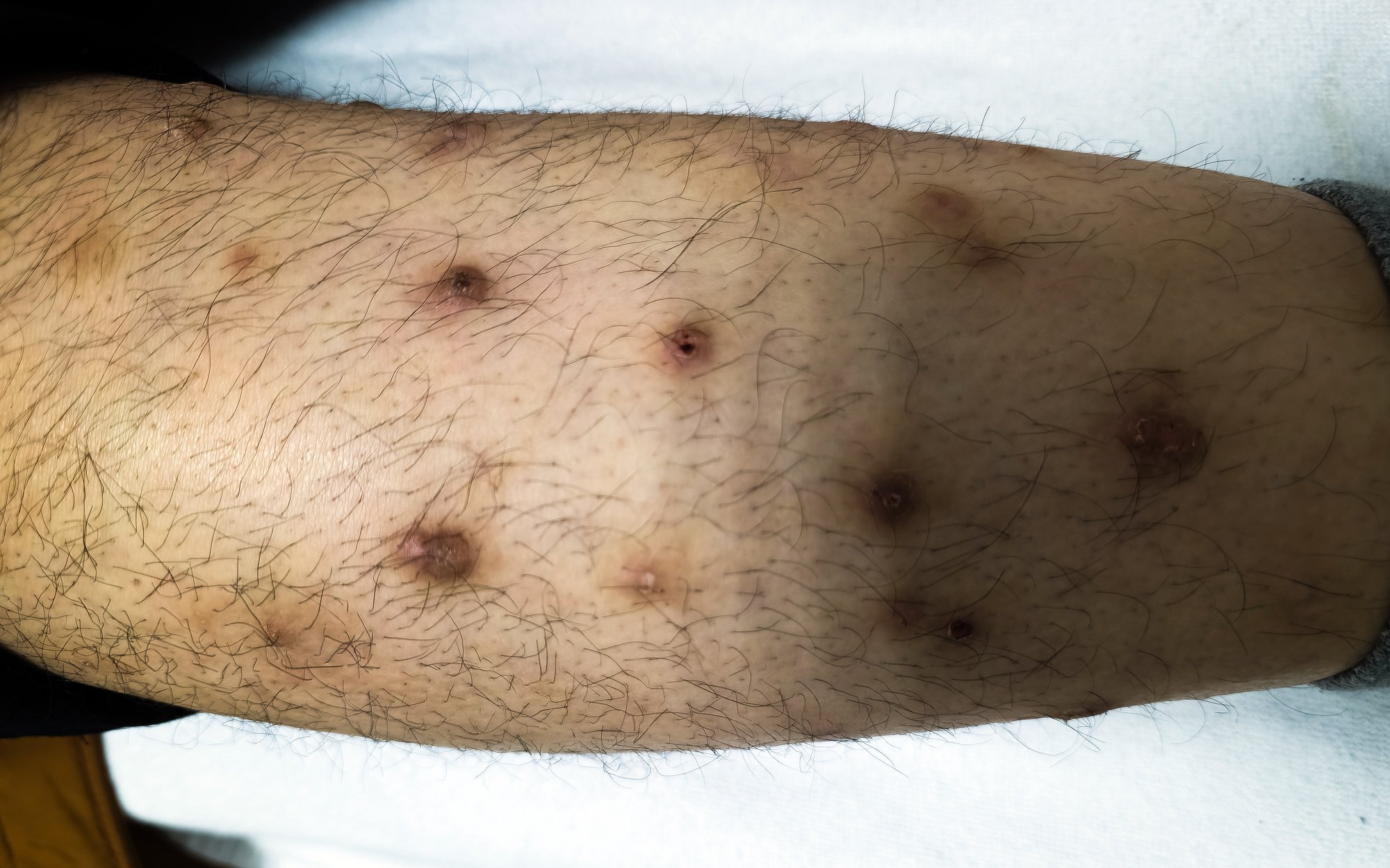

Pulmonary embolism (LE) is grouped together with deep vein thrombosis as venous thromboembolism. Whereas 50 years ago the diagnosis was usually made post-mortem or in the presence of definite clinical findings such as dyspnea, chest pain, or obstructive shock due to limited diagnostic capabilities, the spectrum of LE disease has changed in recent decades. Thanks to the rapid availability of sensitive diagnostic tests, even oligosymptomatic LE with nonspecific complaints or asymptomatic incidental findings can be diagnosed, and not only emboli in the central parts of the pulmonary vasculature can be visualized, but also contrast medium cavities in the small subsegmental pulmonary arteries – so-called subsegmental LE (Fig. 1). The clinical significance of subsegmental LE has been increasingly questioned in recent years, and consequently, the common paradigm that all LE require anticoagulation therapy has been challenged. In the following, we discuss the clinical relevance of subsegmental LE and summarize the current evidence on therapy.

Overdiagnosis of clinically irrelevant pulmonary emboli?

The introduction of multidetector CT angiography (CTA) in the late 1990s revolutionized the diagnosis of LE and gradually displaced other diagnostic procedures. The higher resolution of multidetector CTA compared with ventilation/perfusion scintigraphy or single-detector CTA allows better visualization of small pulmonary vessels such as the subsegmental pulmonary arteries, which increases sensitivity for the diagnosis of LE. With the increasing availability of CT equipment and the large increase in multidetector CTA examinations, there was a relevant increase in LE diagnoses: in the United States, the incidence of LE increased by 80% in the 8 years after the introduction of multidetector CTA. In contrast, mortality decreased slightly by 3% over the same period without any change in the prevalence of risk factors or any relevant improvement in LE therapy. At the same time, however, there was also a 70% increase in anticoagulation-associated complications such as gastrointestinal and intracranial bleeding or secondary thrombocytopenias. The largely stable mortality with relevant increase in LE diagnoses is indicative of overdiagnosis of clinically irrelevant LE. One explanation is the increased diagnosis of small emboli such as subsegmental LE by the more sensitive diagnostic techniques. A systematic review showed that the percentage of subsegmental LE with multidetector CTA doubled compared with the older single-detector CTA (9.4% vs 4.7%). While with the 4-line multidetector CTA the subsegmental ones accounted for 7.1% of all LE, with 64-line multidetector CTA it was already 15%. These results support the hypothesis that technological advances in imaging techniques are responsible for the higher number of diagnosed subsegmental LE and have contributed to the observed increase in the incidence of LE. Subsegmental LE is expected to become even more common as the resolution of new CT scanners improves.

Challenges in the diagnosis of subsegmental pulmonary emboli.

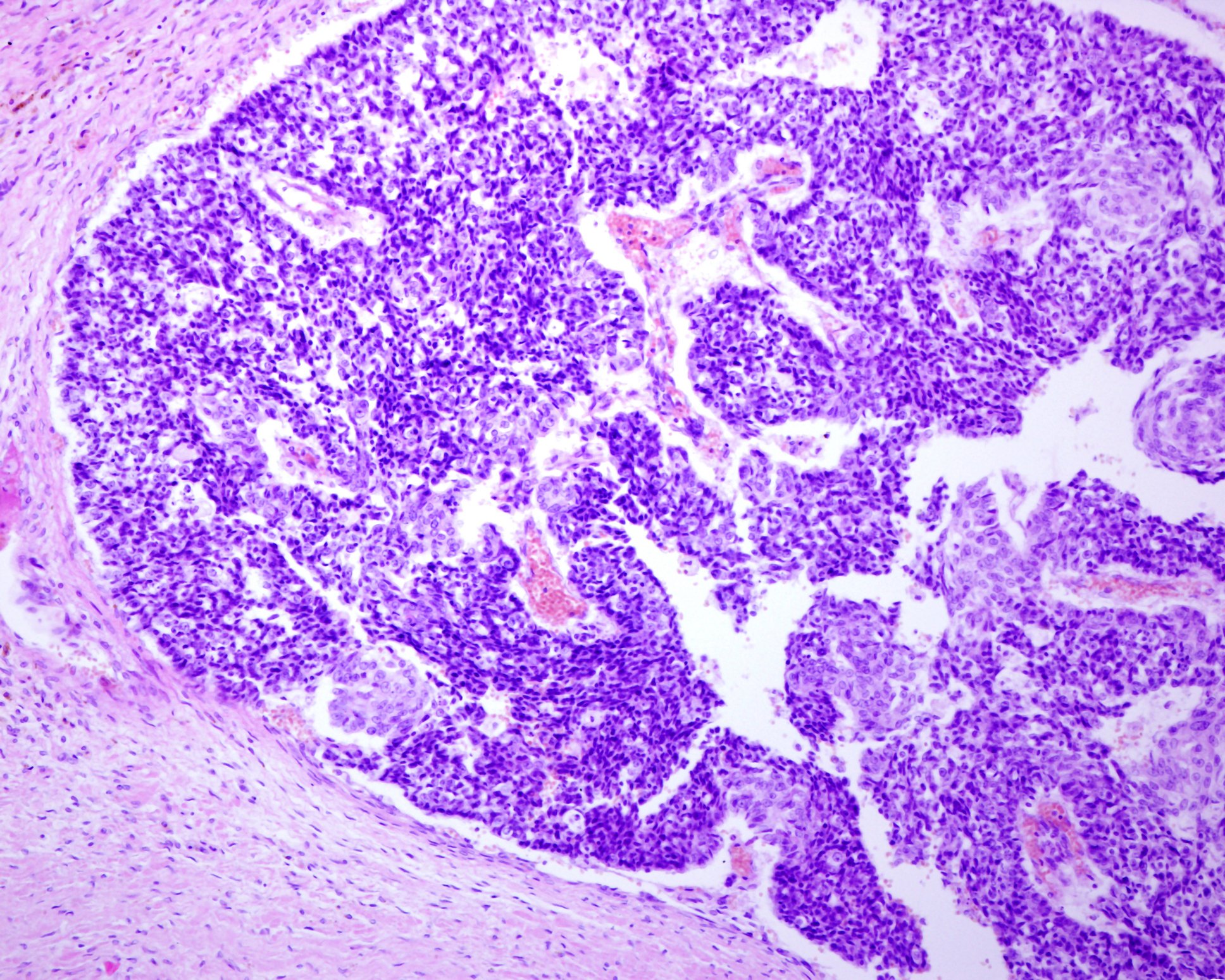

Correct diagnosis of subsegmental LE is difficult, and the distinction between true subsegmental LE and artifact is not always clear. This was illustrated by a study that examined the agreement between radiologists in diagnosing LE depending on its location. In contrast to the high agreement between radiologists in diagnosing proximal LE (kappa=0.83), it was poor for subsegmental LE (kappa=0.23). In another study, subsegmental LE diagnosed by CTA were compared with a reference standard from multiple examination modalities: the positive predictive value of CTA for the diagnosis of embolism in the subsegmental pulmonary arteries was only 25%. Approximately 10-15% of diagnosed subsegmental LE are interpreted as false positives on secondary evaluation. While a recent published study even showed a false-positive rate of over 50%, 8% of presumptive negative CTA findings were missed subsegmental LE (false-negative findings). These findings underscore the importance of good image quality for correct interpretation of CTA findings, because suboptimal contrast, respiratory artifacts, adiposity, or mucus plugging can negatively affect image quality, leading to incorrect findings and overdiagnosis of subsegmental LE. A false-positive LE diagnosis not only results in unnecessary, often lifelong, anticoagulation therapy with its well-known side effects, but may also have other negative effects such as emotional stress or unnecessary follow-up.

There is evidence that the sensitivity of D-dimers is lower in subsegmental compared with more proximal LE. In a diagnostic study, among patients with low clinical pretest probability and D-dimers <1000 µg/l in whom LE was confirmed, 10 of 11 were in subsegmental locations. Using the YEARS algorithm for LE diagnosis, in which a higher D-dimer of 1000 µg/l is the threshold for performing CTA at low clinical pretest probability based on 3 variables, fewer subsegmental LE are diagnosed than with an algorithm based on the usual D-dimer cut-off of 500 µg/l. The use of age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds similarly leads to a reduction in the diagnosis of subsegmental LE.

The pulmonary circulation as a physiological filter?

Individual experts have hypothesized that the pulmonary circulation acts as a physiological filter to prevent small clots from entering the arterial circulation. According to this hypothesis, small LE such as those in the subsegmental pulmonary arteries could also occur in healthy individuals as a result of this physiological filtering function. In a study of healthy subjects, 16% had perfusion defects on lung scintigraphy. Older angiographic observations on the natural history of LE show that even larger emboli can be spontaneously resorbed by endogenous fibrinolytic processes within weeks.

Anticoagulation therapy: benefits and risks

Based on the evidence of overdiagnosis of LE, the risk of false positive findings, and the uncertain clinical relevance of subsegmental LE, it is unclear whether all – including subsegmental — LE require therapy. The usual standard therapy for venous thromboembolism is anticoagulation for at least 3 months. While this therapy is very effective in reducing the risk of thromboembolic recurrence by 80-90%, it also increases the risk of bleeding. The annual risk of major bleeding ranges from 1-5% depending on patient characteristics. Severe hemorrhage is associated with a mortality of approximately 11%, and intracranial hemorrhage in particular, which accounts for approximately 10% of severe hemorrhage, results in relevant morbidity with potentially lifelong disability. Mild bleeding occurs in nearly half of all patients on anticoagulation therapy and is not only a cause of stress and reduced quality of life, but also a burden on the healthcare system due to increased physician visits, medical interventions, and additional costs.

Because of the impact of bleeding complications, the benefits and risks of anticoagulation therapy must always be carefully weighed, especially for thromboembolism of unclear clinical relevance. Using the example of isolated distal deep vein thrombosis, it was shown that not all patients with small venous thromboembolism require anticoagulation therapy. In >90% of isolated distal leg vein thromboses, without treatment, there is neither extension into the more proximal vein segments in the sense of proximal leg vein thrombosis nor other complications. In a randomized placebo-controlled trial in low-risk patients with symptomatic isolated distal leg vein thrombosis, anticoagulation therapy was not superior to placebo for preventing venous thromboembolism, but it resulted in a significantly increased risk of bleeding.

In recent years, the risk-benefit ratio of anticoagulation therapy has also been increasingly questioned in patients with subsegmental LE, because small observational studies have described uncomplicated courses in patients with subsegmental LE even without anticoagulation.

Clinical course in subsegmental LE with and without anticoagulation.

Whether the prognosis differs in subsegmental or more proximally located LE is controversial in the literature. Data from prospective studies showed a similar risk of thromboembolic recurrence, mortality, and bleeding in unselected anticoagulated patients regardless of the anatomic location of the LE. Although these studies do not suggest differences in clinical outcome in treated patients with subsegmental or more proximal LE, they do not provide an answer to the question of whether prognosis differs in subsegmental LE with or without anticoagulation therapy. In addition, these studies did not systematically search for deep vein thrombosis; because undiagnosed deep vein thrombosis may increase the risk of thromboembolic recurrence, they do not provide robust data on prognosis in isolated subsegmental LE (without concomitant leg vein thrombosis).

Subsegmental LE are missed in many cases by certain diagnostic procedures without adverse effects (untreated!). In a randomized trial, patients with suspected LE were evaluated by either multidetector CTA, single-detector CTA, or ventilation/perfusion scintigraphy. Although more LE were diagnosed and thus treated by multidetector CTA compared with the other 2 modalities, there was no difference among the 3 groups in the risk of thromboembolism recurrence at 3 months in untreated patients. Thus, the additional LE diagnosed by multidetector CTA were clinically insignificant. This observation provides indirect evidence that not all small, subsegmental LE are clinically relevant and require anticoagulation therapy. For example, in its guidelines published in 2018, the American Society of Hematology prefers performing planar ventilation/perfusion scintigraphy over CTA for diagnosing LE in certain situations, as the latter is not only associated with increased radiation exposure but also leads to more diagnoses of subsegmental LE with unclear clinical -significance.

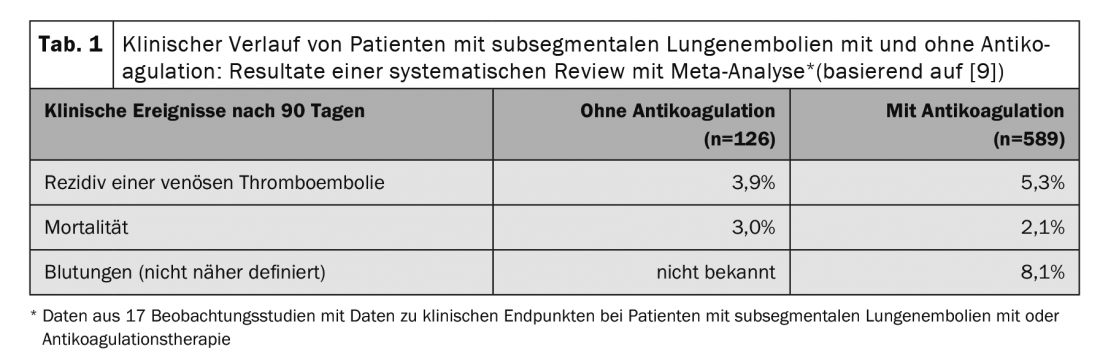

Several small, mostly retrospective, observational studies have compared the clinical course with and without anticoagulation in patients with subsegmental LE. Recently, 14 of these studies were summarized in a systematic review and meta-analysis. In 715 patients with subsegmental LE, thromboembolic recurrence as well as mortality did not differ significantly with or without anticoagulation (Table 1) . These results suggest that patients with subsegmental LE have a similar prognosis to those with therapy even without anticoagulation therapy. However, the included studies have relevant methodological limitations (small sample size, mostly retrospective study design), the included study populations were very heterogeneous, and the criteria for the treatment decision were mostly unknown, which is why the groups of patients with and without anticoagulation are hardly comparable. Data from randomized trials on the safety of a treatment strategy without anticoagulation are currently not available.

Anticoagulation-associated bleeding risk deserves special attention given the questionable relevance of subsegmental LE. The risk of relevant bleeding is highly variable in anticoagulated patients with subsegmental LE, ranging from 1.7% to 34% depending on patient characteristics and bleeding definition.

Management of patients with subsegmental pulmonary embolism: what do the guidelines say?

Based on the limited evidence currently available, various professional societies and expert groups have published recommendations for the treatment of patients with subsegmental LE in recent years. The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guidelines suggest clinical follow-up without anticoagulation therapy in selected low-risk patients with subsegmental LE if coexisting deep venous thrombosis is excluded (weak recommendation with deep evidence). If compression ultrasonography is used to evaluate only the proximal leg veins for the presence of deep vein thrombosis, one or more course ultrasonographies are needed to exclude proximally spreading thrombosis. In high-risk patients (defined as those without reversible risk factors, immobile or hospitalized patients, or those with active cancer or insufficient cardiopulmonary reserves), anticoagulation therapy should be preferred. It is advised to include the risk of bleeding in the treatment decision. Similarly, the American College of Emergency Physicians recommends an individualized treatment strategy based on the patient’s risk profile. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommends that the diagnosis of subsegmental LE be confirmed by an experienced chest radiologist. In ambulatory pa-tients without cancer and without concomitant leg vein thrombosis, a strategy with clinical monitoring without anticoagulation is recommended if only a single subsegmental LE is present, whereas anticoagulation is suggested in all others (including patients with multiple subsegmental LEs). There is no evidence for these different treatment recommendations depending on the number of subsegmental LE, and this distinction is not made in other guidelines and expert recommendations.

Despite these guideline recommendations, most patients with isolated subsegmental LE are anticoagulated today, and the duration of therapy does not differ from patients with proximal localized LE. One possible reason for this is the limited evidence for a therapeutic strategy without anticoagulation – to date, data from sufficiently large, high-quality prospective or randomized trials are lacking.

Outlook

An ongoing international prospective management trial is evaluating a treatment strategy without anticoagulation in low-risk patients with subsegmental LE in whom proximal deep leg vein thrombosis has been ruled out by serial compression ultrasonography (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01455818). In Switzerland, the SAFE-SSPE trial has recently started, a randomized non-inferiority trial in which low-risk patients with isolated subsegmental LE (i.e., without deep vein thrombosis) are randomized to anticoagulation therapy or placebo -(ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04263038). The two treatment groups will be clinically monitored for 90 days and compared for risk of thromboembolic recurrence, bleeding, mortality, and quality of life and economic endpoints. The study will provide information on whether unnecessary treatment with blood thinners can be avoided in selected patients with LE, thereby reducing the risk of bleeding. If a therapeutic strategy without anticoagulation proves safe, the study could initiate a shift away from the current paradigm of anticoagulation therapy for all LE.

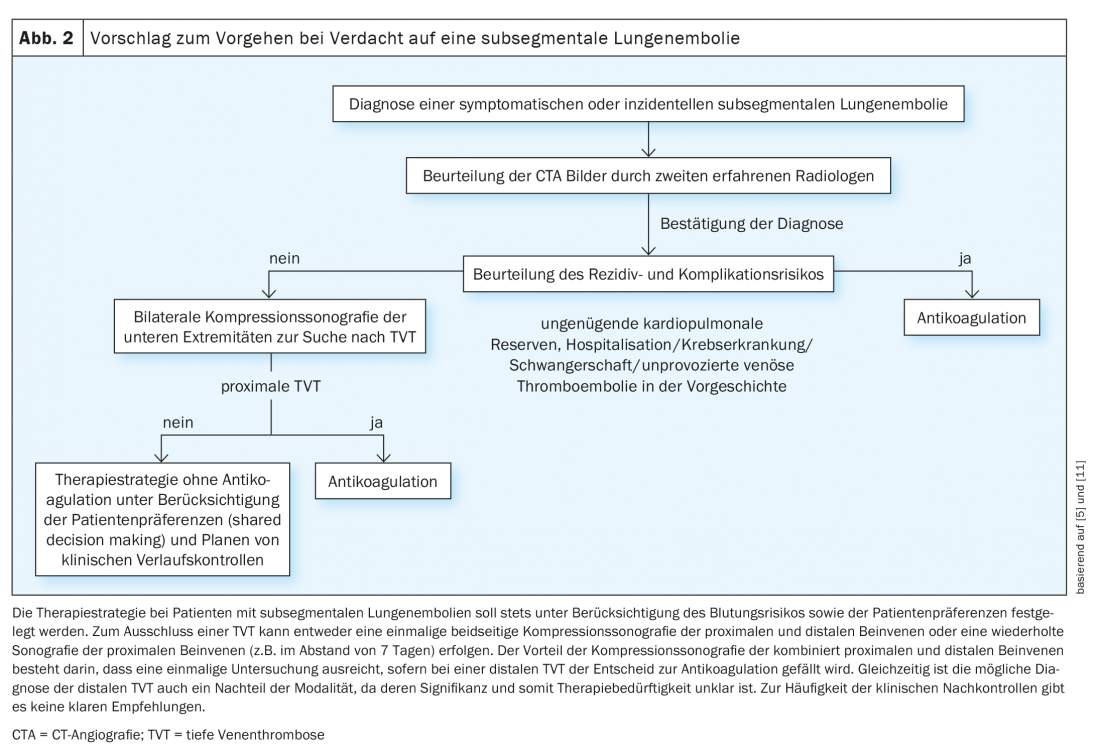

Until robust study results are obtained on the optimal therapy for patients with subsegmental LE, it is important to avoid overdiagnosis and overtreatment. Unnecessary CTA testing can be avoided by using validated diagnostic algorithms with determination of clinical pretest probability and D-dimer testing. For high-sensitivity D-dimer testing, age-adjusted cut-offs, which have been shown to be safe in randomized trials, may further contribute to the reduction of CT examinations, which in turn leads to a reduction in the prevalence of subsegmental LE. The same is true for the aforementioned YEARS algorithm, which is simpler to use and thus may also improve adherence to the correct diagnostic procedure when LE is suspected. Another way to reduce overdiagnosis is to use the PERC algorithm based on 8 clinical criteria in patients with low clinical suspicion of LE. If none of the 8 criteria is positive, further diagnostic testing can be omitted in this low-risk population without missing relevant LE, as shown in a recently published randomized trial. Because of the challenges in diagnosing subsegmental LE explained above, the diagnosis should be confirmed by a second, experienced radiologist before a treatment decision is made – not all suspected subsegmental LE are real! The diagnostic difficulty of subsegmental LE was recently addressed with the publication of radiologic criteria that should be considered when making a diagnosis by CTA. In addition, according to the American Society of Hemtology, assuming local availability and expertise, planar ventilation/perfusion scintigraphy should be preferred to CTA as the diagnostic modality of choice in patients with low or moderate pretest probability and high likelihood of a conclusive finding, among other reasons, to reduce the risk for the diagnosis of subsegmental LE. If subsegmental LE is confirmed, a therapeutic strategy without anticoagulation can be evaluated in selected patients with a deep recurrence and complication risk after exclusion of deep vein thrombosis, especially considering patient preferences and bleeding risk (Fig. 2). This necessitates the performance of compression ultrasonography of the leg veins bilaterally, although the optimal strategy is not known (single compression ultrasonography of the entire proximal and distal leg veins vs. serial compression ultrasonography of the proximal leg veins only).

In summary, the clinical significance of subsegmental LE is unclear, and it is controversial because of the poor evidence regarding optimal therapy. Given the uncertain benefit of anticoagulation therapy in patients with subsegmental LE and profound risk of recurrence and complications, results from high-quality prospective and randomized trials will be of particular importance to avoid potentially unnecessary anticoagulation-associated bleeding complications and to help improve quality of care.

Take-Home Messages

- With the increase in CT scans and technological advances, the incidence of subsegmental pulmonary emboli (LE) increased over the years; they currently account for approximately 15% of all LE.

- The clinical significance of isolated subsegmental LE is unclear.

- The optimal treatment strategy of isolated subsegmental LE (without concomitant deep vein thrombosis) is controversial because of insufficient evidence.

- Current guidelines suggest a treatment strategy without anticoagulation in patients with subsegmental LE, provided concurrent deep vein thrombosis is excluded and there is a profound risk of recurrence and complications.

Literature:

- Wiener RS, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S: When a test is too good: how CT pulmonary angiograms find pulmonary emboli that do not need to be found. BMJ 2013; 347: f3368.

- Wiener RS, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S: Time trends in pulmonary embolism in the United States: evidence of overdiagnosis. Archives of Internal Medicine 2011; 171(9): 831-837.

- Carrier M, Righini M, Wells PS, et al: Subsegmental pulmonary embolism diagnosed by computed tomography: incidence and clinical implications. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the management outcome studies. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis: JTH 2010; 8(8): 1716-1722.

- van der Pol LM, Bistervels IM, van Mens TE, et al: Lower prevalence of subsegmental pulmonary embolism after application of the YEARS diagnostic algorithm. British Journal of Haematology 2018; 183(4): 629-635.

- Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al: Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2016; 149(2): 315-352.

- Carrier M, Righini M, Le Gal G: Symptomatic subsegmental pulmonary embolism: what is the next step? Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis: JTH 2012; 10(8): 1486-1490.

- Stoller N, Limacher A, Mean M, et al: Clinical presentation and outcomes in elderly patients with symptomatic isolated subsegmental pulmonary embolism. Thrombosis Research 2019; 184: 24-30.

- Lim W, Le Gal G, Bates SM, et al: American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Blood Advances 2018; 2(22): 3226-3256.

- Bariteau A, Stewart LK, Emmett TW, Kline JA: Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes of patients with subsegmental pulmonary embolism with and without anticoagulation treatment. Acad Emerg Med 2018.

- Baumgartner C, Klok FA, Carrier M, et al: Clinical Surveillance vs Anticoagulation For low-risk patiEnts with isolated SubSegmental Pulmonary Embolism: protocol for a multicentre randomised placebo-controlled non-inferiority trial (SAFE-SSPE). BMJ Open 2020; 10(11): e040151.

- Swan D, Hitchen S, Klok FA, Thachil J: The problem of under-diagnosis and over-diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Thrombosis Research 2019; 177: 122-129.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2021; 3(1): 4-8.