Intensive research in the field of multiple sclerosis (MS) has led to the availability of different treatment options – depending on the form of the disease and its severity. Until now, the focus of science has been on efficacy and safety in long-term use. In the meantime, the focus has shifted more and more to the individual life situation of female patients in particular. Pregnancy and MS are no longer mutually exclusive.

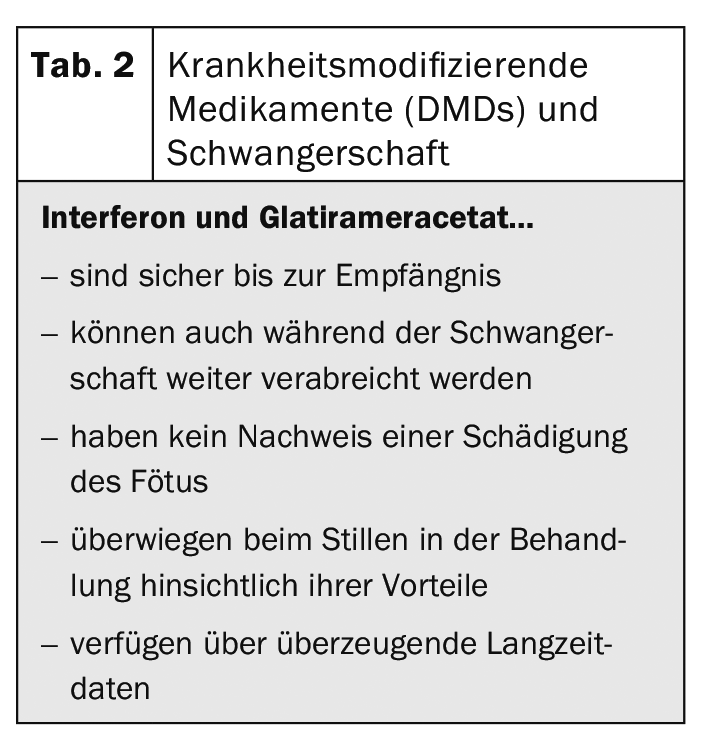

The inflammatory, degenerative disease of the central nervous system primarily affects women, with a ratio of 3:1. And these are predominantly of childbearing age at the time of diagnosis. Lifelong treatment is needed to curb the progression of the disease. It is not only work and social life that are limited by MS – family planning also needs to be carefully considered, as Dr Letizia Leocani, Milan (IT) explained. Because pregnancy has a great influence on the disease. This results in many questions that need to be answered (Tab. 1).

Whether the child inherits the disease depends on several factors. Basically, MS results from an interaction of genetics and environmental factors. The familial frequency is about 15%. If only one parent has MS, the risk that the child will also develop MS is 2%; if both parents have MS, the risk is 20%. But pregnancy also exerts a great influence on the mother and her disease. While the thrust rate is reduced by 70% in the third trimester, it increases significantly after birth. Only after a year does it return to its pre-pregnancy level. This is mainly due to increased hormone production of estrogen, progesterone and prolactin, reduction of pro-inflammatory genes and the shift from Th1 to Th2. The expert therefore advocates planning a pregnancy – ideally only in patients with a stable disease – in order to be able to provide patients with optimal support.

Continue treatment or interrupt – that is the question here

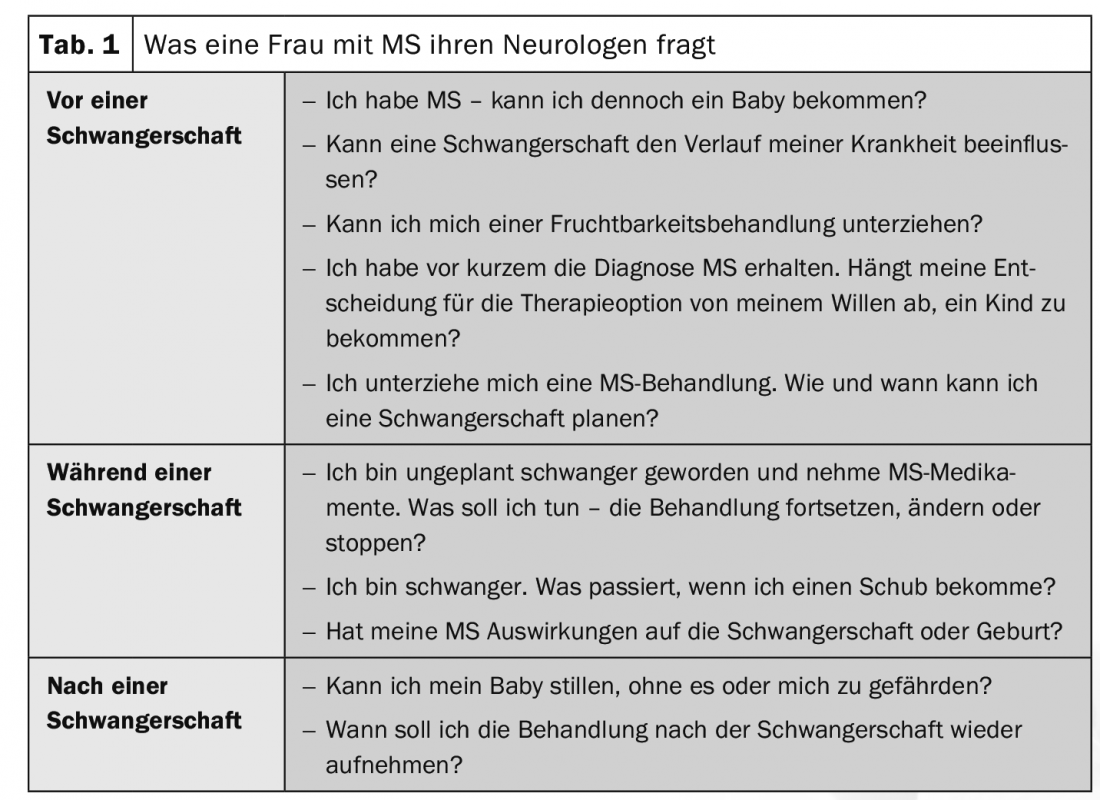

Established immunotherapies such as interferons or glatiramer acetate have convincing long-term data and a good benefit-risk profile. In case of pregnancy, it is necessary to keep in mind the risk for the baby (premature birth, weight, size, maldevelopment) in case of further treatment and the risk for the mother (reactivation of the disease, accumulation of disability) in case of stopping the treatment. In the meantime, there are numerous data regarding therapy management during pregnancy. For example, for interferon beta, the relative risk of congenital anomalies was shown to be 0.51 compared with other MS therapies. Since interferons are large molecules, they do not pass into breast milk, so there is nothing wrong with breastfeeding. The contraindication “pregnancy” could therefore be deleted from the technical information for interferons (Tab. 2) . Therefore, it can be discussed individually with the patient whether the therapy is continued during pregnancy, the expert concluded.

Source: EAN Virtual Congress 2020

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2020; 18(4): 32 (published 6/30/20, ahead of print).