This year’s Swiss Derma Day focused on the management of infectious and immunological skin diseases. Among many other topics, this included the indication and relevance of patch testing and treatment options for vulgar warts.

(ts) “The last few years have shown that epicutaneous testing is being used less and less frequently,” said Prof. Andreas J. Bircher, MD, Basel, opening his lecture on the indication and relevance of patch testing. “However, I believe that this is still a method that belongs in the hands of dermatologists and should be used by us.” He also stressed that while it is easy to perform a patch test, a combination of knowledge and experience/clinical judgment is needed to also assess the relevance of a positive test.

According to Prof. Bircher, patch testing is indicated in cases of suspected contact allergy (contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis) or drug exanthema. “The etiology of contact dermatitis and potentially cross-reacting antigens can only be identified with a patch test,” he reasoned.

Haptens, prohaptens and prehaptens

Classic contact allergens such as nickel ions belong to the category of haptens. That is, they must bind to an endogenous protein to trigger an allergic reaction [1]. Nickel penetrates rapidly through the skin, but requires a Danger signal for sensitization. “According to current research in the mouse model, nickel leads to activation via the toll-like receptor, which is the innate immune system.

Nickel thus has its own Danger signal. This may explain why it is a relatively common contact allergen, but does not explain the clearly existing difference in the frequency of nickel allergy in men and women.”

In addition to haptens, prohaptens are also known. These are themselves chemically less reactive, but can be metabolically transformed in the skin. The preaptenes are also primarily chemically inactive. However, they can become reactive, for example, after spontaneous oxidation. Prof. Bircher gave the example of fragrances and plant substances such as tea tree oil, where contact with oxygen in the air can lead to spontaneous oxidation, turning the prehapten into a hapten.

Implementation and evaluation of a patch test

The speaker then explained how to correctly perform and read a patch test. “Testing is done on the upper back, and if necessary on the outer upper arm. Drug and flexure exanthema should be tested in loco if possible.”

The application period is usually two days, and the first reading should be taken after 20-30 minutes. The second reading can then be taken on Day 3 (72 hr) or Day 4 (96 hr). “Especially with metals and especially also steroids, a late reading should be done after five to seven days, because in these cases we can still see late reactions,” he stressed.

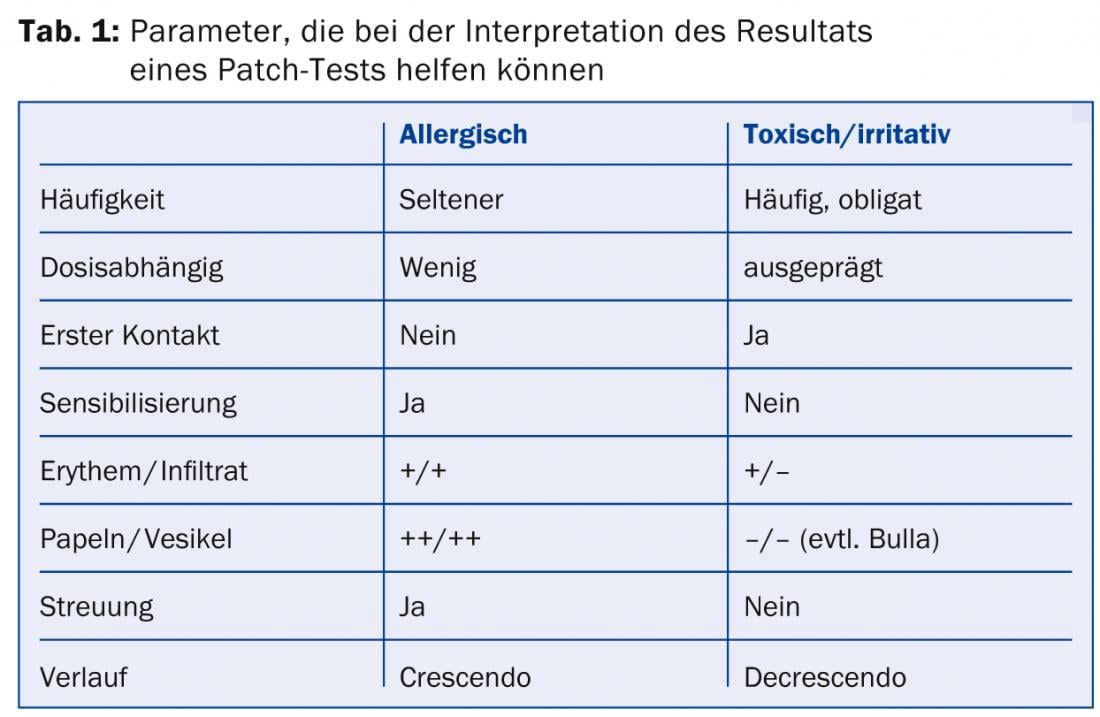

The assessment of the results of a patch test is based on a semi-quantitative system. “Whether the test is negative or positive is still easy to judge,” Prof. Bircher said. “However, assessing the various intermediate stages, such as whether it is erythema with a mild infiltrate, can be difficult. That’s why I think the dermatologist is the only specialist predisposed to accurately assess such lesions.” The interpretation of whether it is a true allergic or more irritant/toxic reaction also requires appropriate knowledge, he said. Parameters such as frequency, dose dependence, dispersion or progression can help here (Table 1).

The allergy passport, a medical document

At the end of his presentation, Prof. Bircher referred to the allergy passport. “Simply writing allergy is not enough here. An accurate clinical diagnosis is needed, e.g., maculo-papular drug exanthema.

It may also be useful to indicate the localization.” In addition, the date of testing and the contact allergens tested should be mentioned, as well as an assessment of relevance. Since allergy passports can be lost, a copy should also be filed in the medical record.

Vulgar warts – course often self-limiting

The lecture by Dr. med. Markus Streit, Aarau, dealt with the crux of vulgar warts. “Typical of these warts is a circumscribed fissured structure. They are usually protruding like domes and have a roughened surface,” he said. However, the image may also vary depending on the location on the body. According to older figures from the United Kingdom, vulgar warts affect 3.9-4.9% among children and adolescents [2]. The prevalence in adults (15-74 years) is reported to be 3.28% [3]. Warts are most often an expression of infection by the human papilloma virus (HPV). “As a viral infection, cutaneous warts actually have a self-limiting course. Thus, after two years, about two-thirds have healed.” However, treatment may still be indicated in certain cases, for example if the changes persist for more than two years, in the case of pain, functional limitations, rapid spread or for cosmetic reasons.

Good evidence for salicylic acid

In principle, methods can be used for the treatment of vulgar warts that lead to the destruction of the tissue by chemical (e.g. keratolytics) or physical means (e.g. cryotherapy) or that have an immunomodulatory or antiviral effect. In addition, there are always stories about various home remedies that can be used to effectively treat warts.

Scientifically sound information on the therapy of vulgar warts is available from a Cochrane Review published in 2012 [4]. This included data from 85 trials with a total of 8815 randomized patients. The review found the best evidence of significant therapeutic success for locally applied salicylic acid vs. placebo. The effect was better on the hands than on the feet in subgroup analyses. Dr. Streit said: “However, it is somewhat surprising that salicylic acid was frequently used in combination in the studies, e.g. with lactic acid or monochloroacetic acid. The results should therefore be taken with a grain of salt. “Still, salicylic acid is certainly what we need most in practice.”

Among the corrosive substances used in practice for local therapy of warts, he mentioned monochloroacetic acid, Solcoderm® (mixture of organic and inorganic acids) and silver nitrate sticks. In terms of cytostatics, 5-fluorouracil and bleomycin are the main drugs used in practice. “The efficacy of 5-fluorouracil is reported in the Cochrane Review as not assessable because the available data were not comparable.” The review also found only inconsistent evidence on bleomycin. However, it was applied differently and at different concentrations in the studies. However, in Dr. Streit’s experience, bleomycin has proven to be a very good option for treatment-resistant plantar warts.

Physical therapy of warts

Among the physical therapy options for warts, cryotherapy ranks first. However, the Cochrane Review found no advantage for this method over placebo [4]. However, in one of the included studies, cryotherapy for warts on the hands proved superior to placebo and also salicylic acid. The application interval (2, 3, or 4 weeks) did not affect cure rates. “Moreover, after four cycles of treatment, continuing the therapy no longer seems to make much sense,” the expert added. According to the review, a more aggressive (>10 sec.) cryotherapy seems to be more effective than a gentle one, but is also associated with an increased risk of side effects such as pain, blistering and scarring.

Finally, immunotherapy with dinitrochlorobenzene was shown to be significantly more effective than placebo in two studies [4]. In conclusion, Dr. Streit noted, “It’s interesting that there are no randomized trials even for some very common methods, such as curettage or excision.”

Source:3rd Swiss Derma Day, January 30, 2014, Lucerne

Literature:

- Karlberg AT, et al: Allergic contact dermatitis – formation, structural requirements, and reactivity of skin sensitizers. Chem Res Toxicol 2008; 21: 53-69.

- Williams HC, et al: The descriptive epidemiology of warts in British schoolchildren. Br J Dermatol 1993; 128: 504-511.

- Rea JN, et al: Skin disease in Lambeth. A community study of prevalence and use of medical care. Br J Prev Soc Med 1976; 30: 107-114.

- Kwok CS, et al: Topical treatments for cutaneous warts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012 Sep 12;9:CD001781.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2014; 24(2): 42-45