The introduction of interferon-free combination therapies with “direct acting antivirals” (DAA) was a breakthrough. Medically, therapy with current drugs can be recommended to all patients with active HCV infection. As of Oct. 1, 2017, several therapies are subject to health insurance coverage regardless of fibrosis stage.

Chronic hepatitis C is one of the leading causes of cirrhosis and liver cancer worldwide. According to estimates by the Federal Office of Public Health, 0.7% of the population in Switzerland is infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV). Infection occurs parenterally, usually in the context of intravenous drug use. In the years before 1980, HCV was also frequently transmitted through transfusions of blood products.

Acute infection is usually oligo- to asymptomatic, and chronic hepatitis C (CHC) develops in 60-80% of patients [1]. The clinical course of chronic hepatitis C is variable. Many patients remain asymptomatic, others suffer from fatigue, poor concentration or joint pain. In most patients, some fibrosis of the liver occurs over years and decades. The prevalence of HCV-induced cirrhosis is 10-20% after 20 years of chronic inflammation [2]. Patients with liver cirrhosis have a significantly increased risk of liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma [3]. In recent decades, CHC has been one of the most common causes of liver transplantation in Europe and North America. However, HCV infection can also cause extrahepatic diseases such as vasculitis, glomerulonephritis, and B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In addition, CHC is associated with insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus and atherosclerosis, and increased risk of cardiovascular events [4].

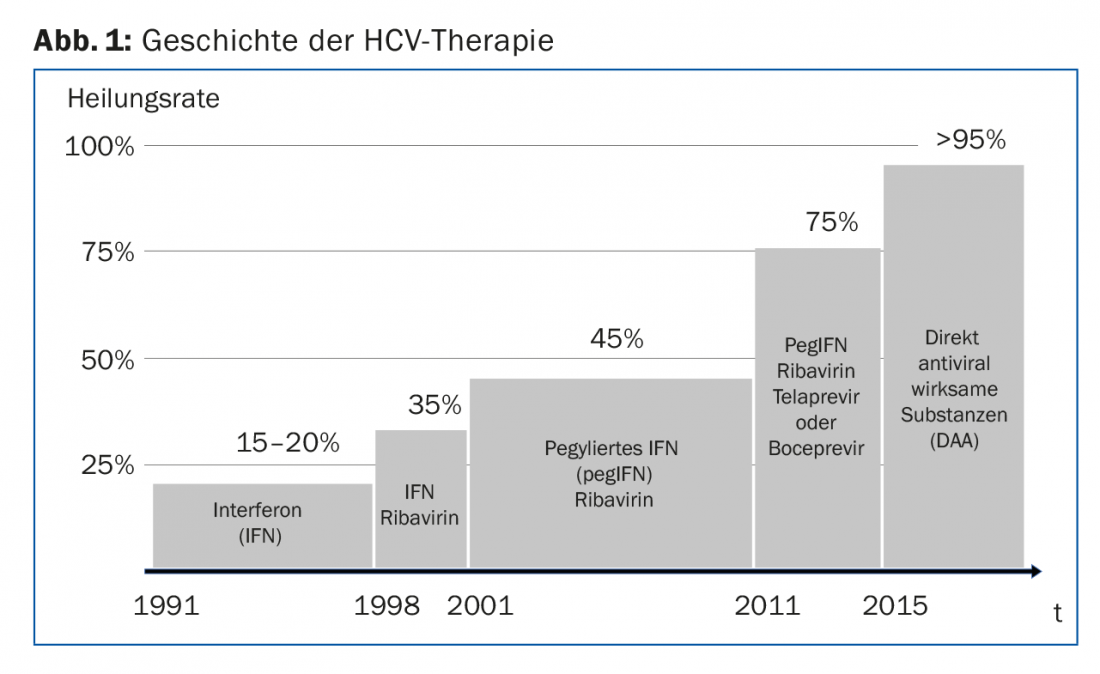

History of HCV therapy

Even before the actual discovery of the hepatitis C virus in 1989, patients with so-called non-A non-B hepatitis were treated with recombinant interferon alpha (IFNα). IFNα binds to specific receptors on the cell surface of hepatocytes and stimulates the expression of several hundred genes with antiviral activity. However, the success of these IFNα monotherapies was modest, with only 15-20% of patients being cured (Fig. 1). The combination of IFNα with ribavirin increased the chances of cure by 15-20%, and the introduction of pegylated IFNα in 2001 by a further 10%. For the next decade, combination treatment with pegylated IFNα and ribavirin was the “standard of care” (SOC) worldwide. Patients with chronic hepatitis caused by HCV genotype 2 or 3 were cured in 75% with six months of therapy. In patients with HCV genotype 1 infection, the cure rate was only 45% despite an extended duration of therapy to 12 months (Fig. 1).

A decisive step was then the introduction of the first direct-acting antivirals (“DAAs”) in 2011. The two HCV protease inhibitors telaprevir and boceprevir were still administered in combination with pegylated IFNα and ribavirin. All therapies based on (pegylated) IFNα had pronounced side effects such as fatigue, myalgias, fever, hair loss, and depression. The breakthrough in the treatment of CHC finally occurred with the introduction of interferon-free combination therapies with two or more DAAs. The cure rates of today’s therapies are over 95%, and they are all very well tolerated.

Current treatment options for chronic hepatitis C.

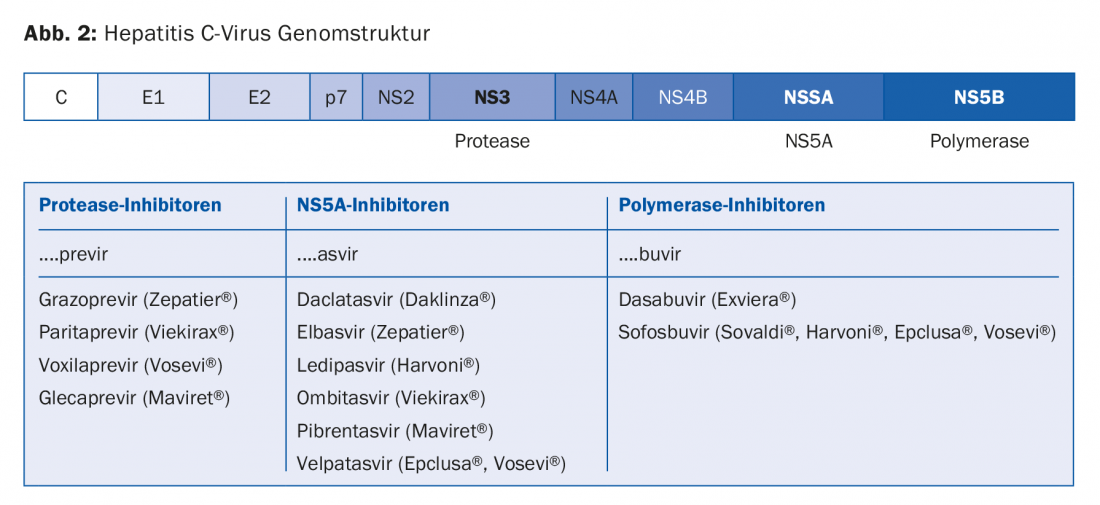

Current IFNα-free therapies are based on drugs that inhibit the function of three viral proteins necessary for viral replication: the HCV protease (NS3), the HCV polymerase (NS5B), and a protein with a not yet fully defined function called the NS5A protein (Fig. 2). The designation of the active ingredients follows a convention that assigns the active ingredients to these three viral proteins: Protease inhibitors end in -previr, polymerase inhibitors in -buvir, and NS5A inhibitors in -asvir. (Fig.2).

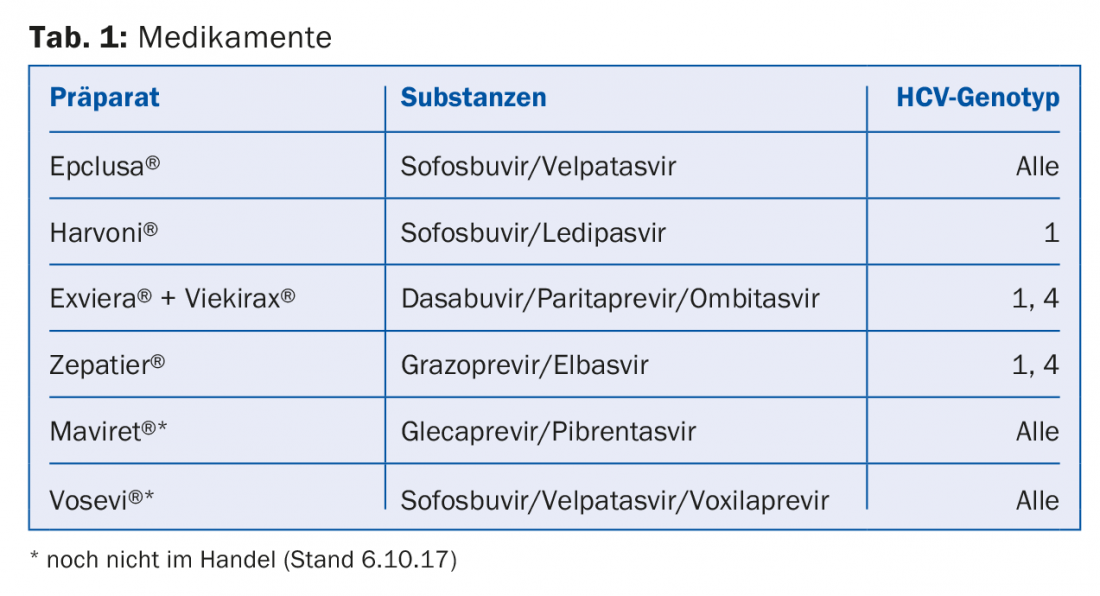

None of the currently available substances should be administered as monotherapy, either because they are not effective enough as single substances or because resistance develops too quickly. Table 1 shows a selection of the drugs currently (and likely in the near future) approved and reimbursed in Switzerland.

The choice of a particular drug, the duration of treatment, and whether a drug should be combined with ribavirin must be determined individually for each patient. Considerations include HCV genotype, whether a patient has had previous unsuccessful treatment (and which), whether cirrhosis is present (and if so, whether it is compensated or decompensated), comorbidities, and the cost of therapy. The prices of the drugs have been constantly decreasing in recent years and it is well worth comparing the current drug prices in each case. As HCV therapies continue to be subject to rapid change, it is advisable to elicit the individual therapy for each patient based on updated recommendations (e.g., on the website of the Swiss Association for the Study of the Liver, SASL, www.sasl.ch) or else via smartphone apps (e.g., the SASL HCV advisor app, https://hcvadvisor.com).

The current therapies are all very well tolerated. Prior to initiating therapy, potential drug interactions with existing long-term medications should be clarified. Appropriate electronic tools, which access continuously updated databases via the Internet (e.g., Epocrates, www.hep-drug-interactions.org), also help here.

How to test for HCV, and whom to treat?

HCV “screening” is based on the determination of antibodies to HCV (anti-HCV) with an immunoassay. Positive (reactive) findings should be verified by HCV RNA detection to confirm the diagnosis of HCV infection.

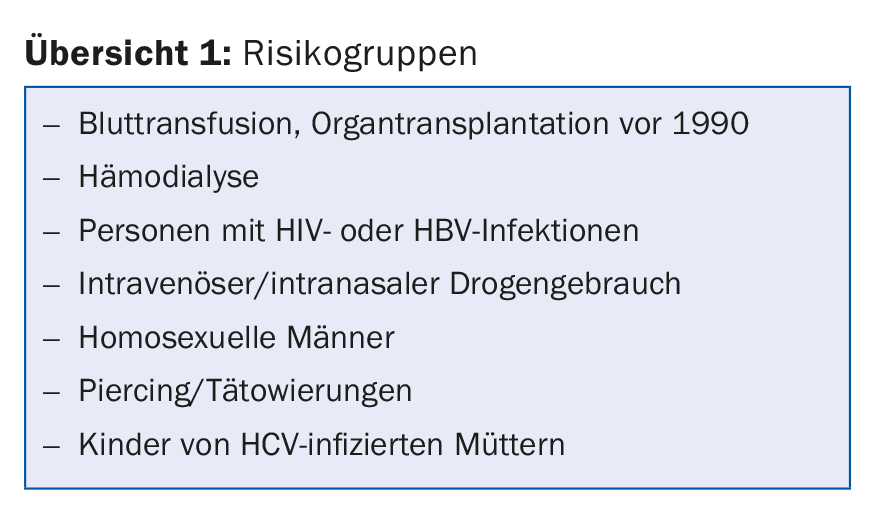

Who should be tested for HCV antibodies now? Basically, safely all patients with clinical or laboratory signs of liver disease. This also applies if there is a high suspicion of another cause such as alcoholic liver disease. Then, individuals who belong to a group at increased risk for HCV infection should also be tested (overview 1) [5].

There are also perfectly good arguments for screening all persons born 1955-1974, regardless of identified risks. It is estimated that over 60% of HCV infections in Switzerland occur in these cohorts. In the USA such birth cohort screenings are established, in Switzerland such a recommendation is still under discussion. Regarding the indication for treatment, it has become internationally accepted that all patients with CHC should be treated regardless of the degree of liver fibrosis. Certainly, the more advanced the liver fibrosis, the more urgent the treatment. Whether treatment of patients who do not have relevant fibrosis of the liver even after decades of CHC is necessary remains controversial. In some of these patients, therapy improves so-called extrahepatic manifestations of HCV infection. It is also possible that HCV eradication may preventively reduce the risk of extrahepatic disease, such as the development of coronary artery disease. Finally, there are preventive arguments regarding the HCV epidemic, especially for patient groups who are at relevant risk of infecting others with HCV.

For all the above reasons and others [6], from a medical point of view, therapy of all patients with active HCV infection with the current drugs can be recommended, especially because they are very well tolerated and, at least according to the current state of knowledge, very safe. Whether such a strategy makes economic sense at today’s drug prices remains controversial and is ultimately probably a matter of judgment.

Before, during and after therapy

Prior to therapy, a site assessment of HCV infection should be performed in addition to a general assessment of comorbidities. This includes determination of the blood count, liver values including bilirubin, as well as albumin and INR. HCV genotype and HCV “viral load” should be determined. It is of great importance to clarify whether cirrhosis is present. The presence of cirrhosis may impact the choice of medications and duration of therapy. Most importantly, the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma is significantly increased in patients with liver cirrhosis. These patients should be screened with six-monthly liver ultrasounds as a precaution. Based on current knowledge, the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotics remains significantly elevated even after successful therapy for HCV infection. Therapy of patients with CHC without prior clarification of whether cirrhosis is present must therefore be clearly classified as poor medical practice.

The stage of liver fibrosis and the presence of cirrhosis can be determined by various methods. The gold standard is still liver biopsy. Because this is an invasive examination, other procedures are also widely used. In Switzerland, transient elastography using Fibroscan® has become particularly popular. This examination is offered at many hepatology centers and specialty practices, is painless for the patient with no risk of complications, and has reasonable sensitivity and specificity for detecting and ruling out liver cirrhosis.

Light at the end of the tunnel

After nearly three decades of severely limited treatment options, during which CHC was one of the most common causes of cirrhosis in Europe and the United States, the outlook for patients with CHC has improved greatly in the last three to five years. The development of highly potent and specifically antiviral drugs must be classified as a unique success story in medical research. HCV is the only chronic viral infection that can be virologically cured (eradication of the virus) with drug therapy. Shortly after their market launch in 2015, DAA therapies were exorbitantly expensive: for example, a 6-month therapy of genotype 3 infection with Sovaldi® and Daklinza® cost over CHF 180,000. The high prices have triggered fears at the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) of a further surge in healthcare costs. In response, the new therapies were given a limitatio. Initially, only patients with far advanced fibrosis could be treated (fibrosis stages 3 and 4 on a scale of 0 to 4; stage 0 = no fibrosis, stage 4 = cirrhosis). When additional drugs were introduced to the market, the limitatio was extended to fibrosis stage 2. The limitation of these highly effective therapies to patients with advanced fibrosis stages has caused disappointment and outrage among patients with deeper fibrosis stages. The whole process of proving a higher fibrosis stage and the cost approval procedures consumed considerable financial and human resources.

Fortunately, the last negotiations between the FOPH and the pharmaceutical companies involved have now led to a significant price reduction of the drugs, which apparently allowed the FOPH to lift the limitatio regarding fibrosis stage. As of Oct. 1, 2017, several therapies are covered by insurance for all patients with CHC, regardless of the fibrosis stage of the liver.

Another bright spot is the increasing simplification of therapy. In the foreseeable future, at least two preparations will be available that can be used in all genotypes, in patients with or without cirrhosis, and in patients with or without pretreatment (this with certain limitations) (Table 1). Actually, it would then be time to remove the last Limitatio: the restriction of prescribing to specialists in gastroenterology or infectiology (as well as by selected physicians with experience in addiction medicine and in the treatment of CHC). Most hepatitis C treatment could already be easily provided by primary care providers. Non-pretreated patients without cirrhosis and without relevant comorbidities do not need specialist care for HCV therapy. It is to be hoped that the restriction of prescribing to a few specialists will also soon be lifted by the FOPH.

Take-Home Messages

- The introduction of interferon-free combination therapies with two or more “direct acting antivirals” (DAA) was a breakthrough. The cure rates are over 95%, with very good tolerability. HCV is the only chronic viral infection that can be virologically cured with drug therapy.

- The choice of drug, the duration of treatment, and whether a drug should be combined with ribavirin should be determined on an individual basis. In the foreseeable future, at least two preparations will be available that can be used in all genotypes, in patients with/without cirrhosis, with/without pretreatment (this with certain limitations).

- Medically, therapy of all patients with active HCV infection with current drugs can be recommended.

- Fortunately, as of Oct. 1, 2017, several therapies are covered by insurance for all patients with chronic hepatitis C, regardless of fibrosis stage.

Literature:

- Heim MH, Bochud PY, George J: Host-hepatitis C viral interactions: the role of genetics. J Hepatol 2016; 65: S22-32.

- Thein HH, et al: Estimation of stage-specific fibrosis progression rates in chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Hepatology 2008; 48: 418-431.

- El-Serag HB: Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2012; 142: 1264-1273.

- Negro F, et al: Extrahepatic morbidity and mortality of chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 2015; 149: 1345-1360.

- Fretz R, et al: Hepatitis B and C in Switzerland – healthcare provider initiated testing for chronic hepatitis B and C infection. Swiss Med Wkly 2013; 143: w13793.

- Bruggmann P: Hepatitis C epidemiology in Switzerland and the role of primary care. Praxis 2016; 105: 885-889.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(10): 28-32