Post-mortem donor organs are scarce. Experts are therefore increasingly turning to living donations – with advantages but also risks.

The first successful living-donor kidney transplant between identical twins occurred more than 60 years ago on December 23, 1954, at Brigham Hospital in Boston. The questions that donors and relatives asked at that time regarding long-term risks such as terminal renal failure and life expectancy, as well as the need for lifelong follow-up, continue to be the subject of current research and are little different from the questions asked by living donor couples today. Although the first successful living kidney donation was performed in Basel on February 6, 1966, it was rarely performed in Switzerland until the early 1990s. Due to the increasing waiting time for post-mortem donor organs, as well as advances in immunosuppressive therapy, which also made blood group incompatible kidney transplantation possible, and a liberalization of donor criteria, the proportion of living donations increased steadily in the following years. In 2017, 128 living kidney donations were performed in Switzerland, representing 35% of all kidney transplants. The main advantages of living kidney donation from the recipient’s perspective include better kidney graft survival, the possibility of preemptive transplantation without prior dialysis therapy, and the ability to plan the procedure.

Preparatory medical clarifications

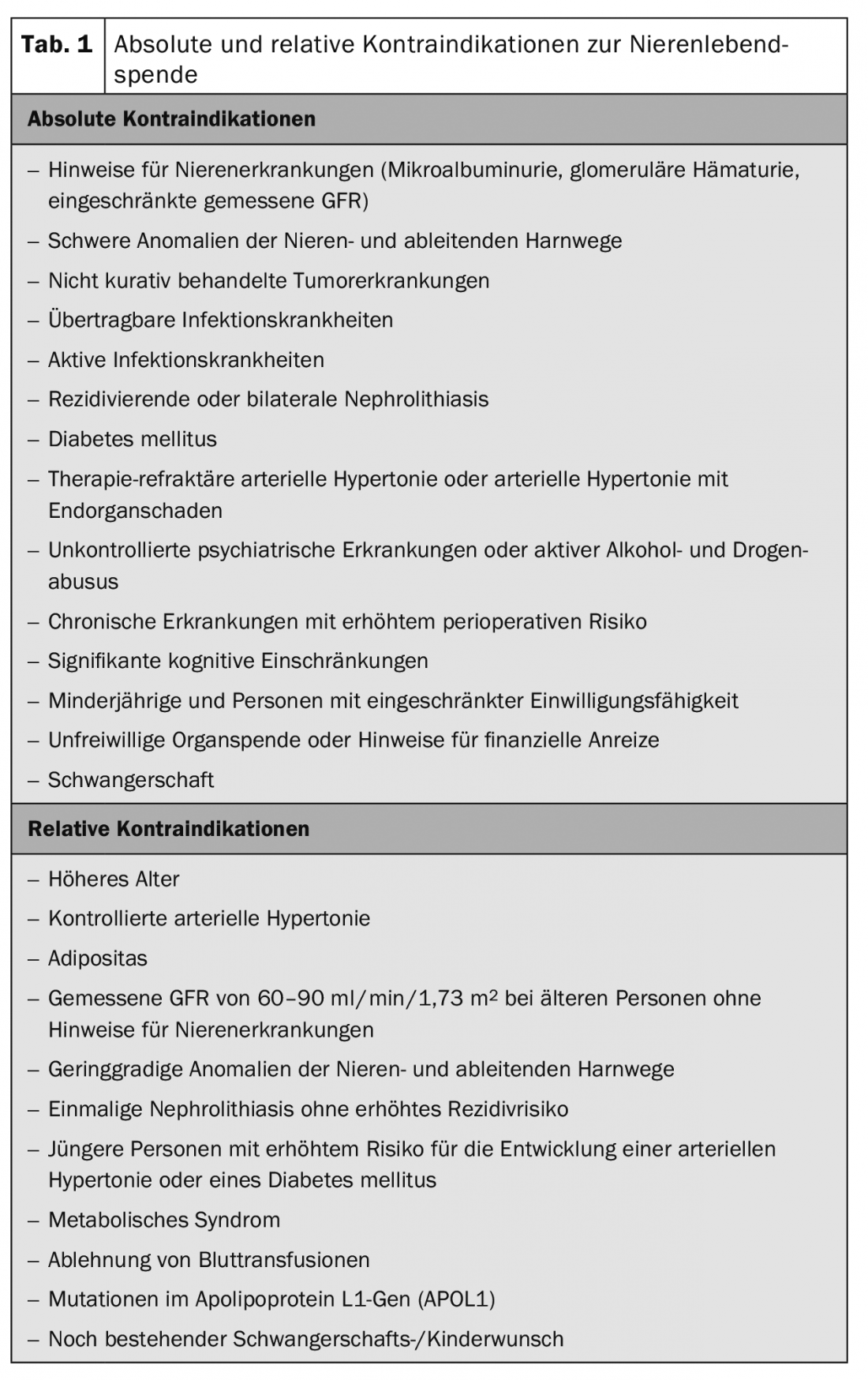

For living donation to be successful, a number of conditions must be met for both donor and recipient, generally summarized as absolute and relative contraindications (Table 1) [1].

In any donor evaluation, the safety of the donor is the highest priority. In addition to the psychosocial situation and clarification of the immediate risks, the long-term cardiovascular risks must also be evaluated. Furthermore, immunological compatibility with the potential recipient and the risk of transmission of infectious or tumor diseases from the donor to the recipient must be assessed.

Assessment of renal function: One focus of the evaluation is the determination of renal function, which is assessed not only on the basis of the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR), but also with the measured creatinine clearance and, if necessary, with the aid of a scintigraphy. In addition, evaluation of the urine (proteinuria/urine sediment) is performed as a possible indication of kidney disease. Computed tomography is performed for accurate evaluation of renal vascular anatomy, but also to assess structural abnormalities (cysts, calculi, etc.) [2].

Clarification of the immediate risks: In view of the surgical and anesthesiological risk, attention is paid to diseases of the heart and lungs. ECG, echocardiography and chest X-ray are the basic examinations. Depending on the medical history and cardiovascular risk profile, a decision is then made as to whether and, if so, which further examinations (ergometry, stress echocardiography, computed tomography of the thorax, etc.) are still necessary. Potential donors with relevant pre-existing cardiovascular conditions will not be accepted for donation.

Clarification of long-term cardiovascular risk: arterial hypertension is the main long-term medical risk. For this reason, clarification of blood pressure is essential. Hypertension per se, is not a contraindication for donation depending on donor age, quality of blood pressure control and in the absence of end organ damage.

Pronounced obesity poses a medical and surgical risk for donation, a BMI >35 kg/m2 is generally considered a contraindication for donation, with a BMI of 30-35 kg/m2 the situation must be carefully evaluated, there should be no other significant cardiovascular risk factors [3].

Diabetes mellitus is usually a contraindication for donation.

Prevent transmission of diseases: An age-adapted tumor screening (women: gynecology/PAP/mammography, men: urology), dermatological screening and a colonoscopy (from the age of 50 or earlier if there is a positive family history) is performed on the donor not only to assess possible transmission to the recipient. They also serve to exclude relevant comorbidities. This is also intended to avoid exposing donors to an increased risk of morbidity due to possible tumor therapy in uniparental patients. Regarding infectious diseases, screening for hepatitis A, B, C, E and HIV as well as CMV and EBV serology and other infectious diseases is performed.

Further examinations are based on the patient’s history and the clinical examination findings.

Clarification of immunological compatibility: The clarification of immunological compatibility includes the determination of the blood group, whereby living kidney donations can also be performed in the case of ABO incompatibility, and HLA typing. In addition, the recipient’s serum is tested for antibodies against donor-specific HLA antigens.

Psychosocial assessment: Psychosocial aspects assessed in the donor assessment include motivation for living donation, relationship with the recipient, psychosocial history, decision-making process, handling of psychosocial stress situations, and current life circumstances.

Acceptance of donors with Isolated Medical Abnormalities: Due to the long waiting period for post-mortem donor organs, since the turn of the millennium there has been increasing pressure to accept donors for living donation who do not meet the strict requirements, mostly due to one criterion. The term Isolated Medical Abnormalities, which may be tolerated for living donation in individual cases, includes the following abnormalities:

- Higher donor age need not be a contraindication in individual cases. Donors over 90 years of age are reported in individual centers.

- Arterial hypertension that is well controlled with a maximum of two antihypertensive medications need not be a contraindication – if the cardiovascular risk is otherwise low.

- Patients with grade 1 obesity without arterial hypertension and glucose metabolism disorder can be evaluated for living donation.

- A restricted measured GFR of 60-90 ml/min/1.73 m2 can be evaluated in older donors within the framework of physiological nephron loss and can be tolerated in individual cases.

Operation procedure

Open donor nephrectomy is no longer performed in Switzerland; all centers operate with minimally invasive procedures. This is often done by laparoscopic hand-assisted nephrectomy. Depending on the anatomy of the kidneys and the donor, the surgery usually takes between 90 and 180 minutes.

Risks of living kidney donation

Risks associated with living kidney donation can be specifically divided into those that are directly related to the surgical procedure and those that do not become apparent until months to years after living kidney donation.

Perioperative risks of living kidney donation: The major perioperative risks of living kidney donation include intra-abdominal hemorrhage and infection, postoperative infections such as pneumonia, urinary tract infection, or wound infection, and ileus, pneumothorax, and deep vein thrombosis. However, serious surgical complications requiring surgical revision or transfusion of blood products are rare. Perioperative mortality is markedly low and is reported to be approximately 3‰. Late surgical complications such as paresthesias in the scar area or scar hernias, which are most commonly associated with the open nephrectomy that used to be common, are generally harmless but may contribute to a lower quality of life. The duration of convalescence after living kidney donation is usually short, so that living donors can leave the hospital after a few days and are generally fully able to work after one to three months [4].

Long-term risks of living kidney donation: Most studies of long-term outcomes after living kidney donation must be viewed highly critically for several reasons. Especially since an optimal control group is missing, namely patients who were positively evaluated for living donation but did not donate a kidney.

This problem was first attempted to be addressed by two studies in 2013 and 2014 by selecting well-designed control groups from national health studies. These included individuals who themselves met the criteria for living kidney donation. According to these studies [5], living kidney donors show a low absolute risk of developing ESRD themselves, but a significantly increased relative risk compared to the control group. In a recent 2018 meta-analysis that looked at three studies when asked about the risk for end-stage renal failure – including the studies from Norway and the U.S. just mentioned – the relative risk of developing end-stage renal failure after living donation was about eight times higher than for non-donors. The risk of end-stage renal failure was found to be increased in obese donors in particular.

However, the following problems continue to make generalization of the current results difficult:

- These are almost exclusively cross-sectional studies.

- There is predominantly an estimation of glomerular filtration rate in the follow-up rather than a measurement.

- Most studies have a markedly short follow-up period.

- The gradual liberalization of donor criteria, in particular the acceptance of young overweight donors or those with manifest hypertension, are so far insufficiently captured in current studies.

In a very recent paper on arterial hypertension after living kidney donation, 4%, 10%, and 51% of donors developed arterial hypertension within 5, 10, and 40 years, respectively. Both the risk factors for arterial hypertension and the association with the development of proteinuria, cardiovascular disease, and mortality were comparable to the normal population [6]. Consistent management of arterial hypertension after living kidney donation therefore appears particularly important. Specifically, it should be noted that gestational hypertension and preeclampsia are approximately two and a half times more common in pregnancies of kidney donors than in non-donors [7].

In a meta-analysis that included 52 studies and a total of more than 100,000 kidney donors and non-kidney donors, there was no evidence of decreased life expectancy, increased risk of cardiovascular disease, or decreased quality of life [8]. Although some studies have associated decreased performance and chronic fatigue with living kidney donation, even leading to decreased work and earning capacity in isolated cases, a direct association remains scientifically uncertain due to the high incidence for the occurrence of unexplained fatigue in the general population.

Follow-up after living kidney donation

The lifelong aftercare of donors is an important aspect and is organized in an exemplary manner in Switzerland and has meanwhile been firmly implemented in the Transplantation Act (Article 15a). Swiss transplant centers have delegated this duty to the Swiss Living Donor Registry SOL-DHR, as they did before the legal implementation. The cost of follow-up care must be borne by the recipient’s health insurance company. At the time of donation, a mandatory one-time lump sum must be transferred to the Living Donor Aftercare Fund (SOL DHR). Follow-up in each case includes a questionnaire, as well as monitoring of blood pressure, creatinine level, protein/albuminuria, and an assessment of sediment. If blood values are abnormal, the donor will be contacted by the registry with a recommendation for further testing.

Conclusion

Although the relative risk for progression to ESRD appears to be increased after living kidney donation, the absolute risk for this is extremely low. To prevent any long-term complications, consistent nephrological follow-up of living kidney donors is of paramount importance. [9,10]

Take-Home Messages

- Safety for the living donor is an absolute priority.

- Every third kidney transplant in Switzerland is a living donation.

- Nor is advanced age per se a contraindication to living kidney donation.

- Acceptance of donors with Isolated Medical Abnormalities possible on a case-by-case basis.

- Development of arterial hypertension as the most important long-term complication after living kidney donation.

- Increased relative risk of end-stage renal failure after living kidney donation with extremely low absolute risk.

- No reduction in life expectancy and quality of life, with cases of decreased performance and fatigue reported.

Literature:

- Lentine KL, et al: KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Care of Living Kidney Donors. Transplantation 2017; 101: 1-109.

- Mueller TF, Luyckx VA: The natural history of residual renal function in transplant donors. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 23(9): 1462-1466.

- Locke JE, et al: Obesity increases the risk of end-stage renal disease among living kidney donors. Kidney Int 2017; 91(3): 699-703.

- Segev DL, et al: Perioperative mortality and long-term survival following live kidney donation. JAMA 2010; 303(10): 959-966.

- Muzaale AD, et al: Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA 2014; 311: 579-586.

- Sanchez OA, et al: Hypertension after kidney donation: incidence, predictors, and correlates. Am J Transplant 2018; 18(10): 2534-2543.

- Garg AX, et al: Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia in living kidney donors. N Engl J Med 2015; 372(2): 124-133.

- Lam NN, et al: Long-term medical risks to the living kidney donor. Nat Rev Nephrol 2015; 11(7): 411-419.

- Gross CR, et al: Health-related quality of life in kidney donors from the last five decades: results from the RELIVE study. Am J Transplant 2013; 13(11): 2924-2934.

- Mjøen G, et al: Long-term risks for kidney donors. Kidney Int 2014; 86(1): 162-167.

CARDIOVASC 2019; 18(1): 12-15