About half of the Swiss cantons now offer a breast screening program. The goal of systematic breast screening is to reduce mortality. Discussions about the benefits of breast screening are often emotional.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and also the leading cause of cancer-related death among women in the Western world. Nearly one in eight women will develop breast cancer during her lifetime. In Switzerland, about 5900 women are newly affected each year, and about 1400 die from it annually [1]. 80% of new cases occur in women after the age of 50. The National Strategy Against Cancer still predicts an increase in new cancer cases in the coming years [2,3]. However, breast cancer-specific mortality has been decreasing since the 1990s due to early detection and improved adjuvant therapy [1].

To date, there is no possibility of “screening” in the true sense of the word that could effectively prevent the occurrence of breast cancer. For this reason, the only chance to reduce mortality is to detect and treat the disease at the earliest possible stage through early detection.

The goal of reducing breast cancer mortality in the population requires population-based interventions accordingly. It must be remembered that such ventures involve apparently healthy members of society who are clinically asymptomatic with respect to the disease. In these two aspects (reference to a population group and freedom from symptoms of the target group), early detection differs quite substantially from the usual “curative” medical care.

Methods for early detection of breast cancer

For the early detection of breast cancer, mammography has so far been the most suitable procedure. It can also be made available to a broad section of the population under economically and organizationally acceptable conditions. Mammography is therefore the method recommended as the basis for screening in all international guidelines and is also used internationally in all screening programs [4].

Although manual self-examination is more economical, it has been shown to result in a higher biopsy rate with mostly benign findings, and a reduction in mortality has not been demonstrated. Even professional palpation by specially trained personnel does not provide sufficient accuracy with respect to the population.

Sonography is hardly feasible as the sole screening measure for a broad population due to the high time required and is methodologically too inaccurate with, in addition, high interobserver variability. However, it is used in some screening programs (e.g., in Austria) as a supplementary examination in the initial screening process when breast density is high.

Breast MRI cannot be used for general screening for reasons of economy and availability, but finds its justification in the context of intensified screening for high-risk patients (e.g., BRCA mutation carriers).

Organization of population-based screening

There has been an increased awareness in society of the problems associated with advanced breast cancer. The taboo surrounding this topic has largely been lifted. For these reasons, in recent years, outpatient breast examinations have been increasingly performed in symptom-free women from about 50 years of age. This is sometimes referred to as “gray” or “opportunistic” screening. The voluntary nature of the examination and the immediate communication of the findings by the examining physician are listed as advantages. However, the lack of equal opportunities for access to such care and the lack of clarity regarding quality due to a lack of data transparency and inhomogeneous care structures are disadvantages. Thus, for “gray” screening, society has no knowledge of the efficiency of the resources used, the actual number of participants, or even the population-based effectiveness of screening.

Systematic screening in the form of a mammography or breast screening program addresses these deficiencies. The basis of such a program is a social decision with a government policy mandate that defines the population group eligible to participate and specifies the diagnostic method and organizational structures. The programs are controlled with dedicated quality management and regular reports of key process and outcome indicators (“key performance” indicators) [4]. The results of a national program can thus be measured against other international programs.

Mammography screening in Switzerland

Mammography screening programs now exist in all European countries, in some cases for almost 30 years (e.g. in England, the Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands).

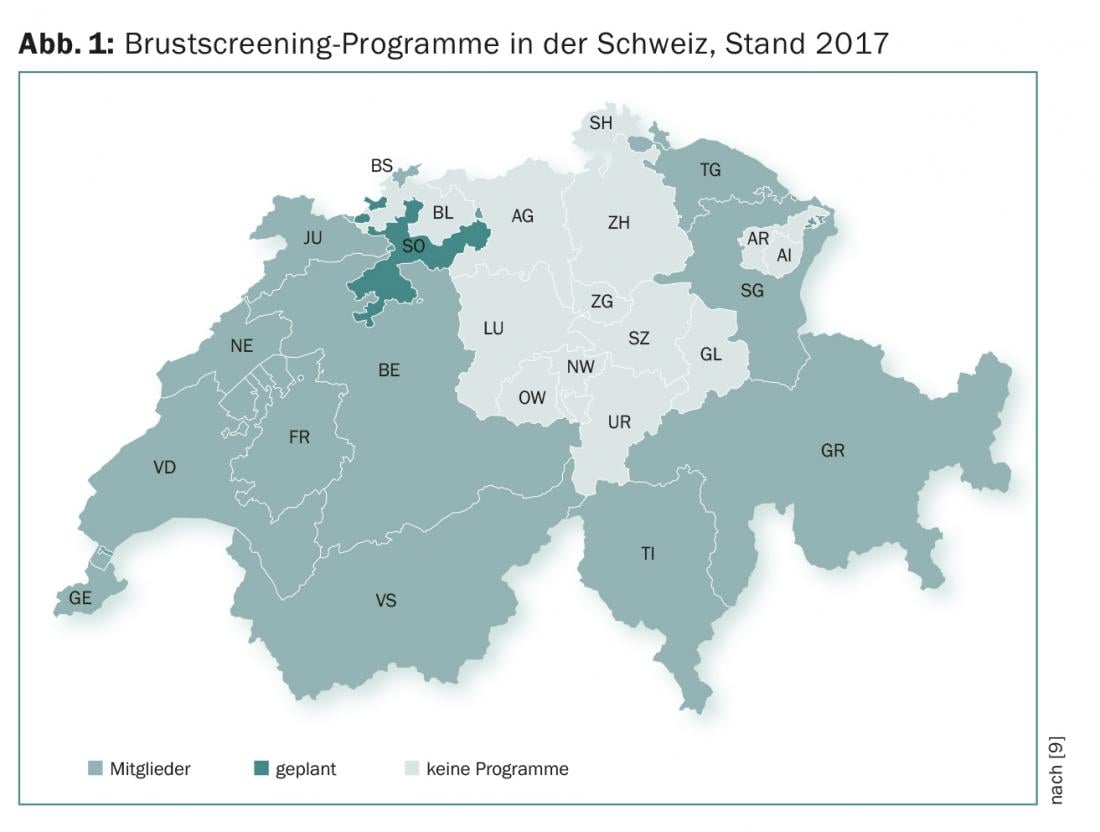

In Switzerland, the cantons are responsible for deciding on the introduction and implementation of a breast screening program. The first pilot projects were already running in the canton of Vaud from 1993. The French cantons FR, GE, JU/NE, VD and VS have been implementing breast screening programs for more than ten years. In the meantime, about 60% of women living in Switzerland have access to a breast screening program (Fig. 1) . The cantonal programs show similarities in most points, which are essentially based on the specifications of the European guideline [5] as well as special Swiss regulations at the federal level [6–8] and are defined in cantonal program guidelines.

According to the National Strategy against Cancer, the Swiss Cancer Screening Association [9] is responsible for coordinating the screening programs of the cantons, harmonizing quality standards, and communicating the performance goals and contents of the programs to the reference group and the rest of the population.

Mammograms performed as part of cantonal screening programs are reimbursed by health insurance in accordance with the Health Care Benefits Ordinance (Krankenpflege-Leistungsverordnung, KLV; SR 832.112.31) and are exempt from the deductible rate. The prerequisite for this is a program organized on a cantonal basis and compliance with the European quality requirements adapted to Switzerland. For providers in the breast screening program, these include participation in special introductory and regular refresher courses, as well as demonstrated annual minimum case numbers (for MTRA: mammograms in at least 300 and 1000 women per year, respectively; for physicians: mammogram readings in at least 2000 and 3000 women per year, respectively [6]).

In the programs, all women between the ages of 50 and 69 (up to 74 in some cantons) who are registered residents of the canton are invited for mammography every two years at specially accredited and regularly screened mammography sites. Screening examinations are deliberately separated in space and/or time from normal patient care to avoid a sense of patient role among apparently healthy screening participants and associated psychological distress.

In all programs, mammography alone is the diagnostic method of choice. All mammograms are read independently by two radiologists. In the event of a discrepancy or abnormality, the images are evaluated in an institutionalized consensus conference by the two radiologists involved plus at least one other radiologist as conference chair. This process is controlled and documented in all cantons with the same special software. This is also used to manage deadlines and other relevant data, as well as to organize internal processes. The software is also used to generate the reports on the result of the mammography and send them to the participants and to the doctors they specify.

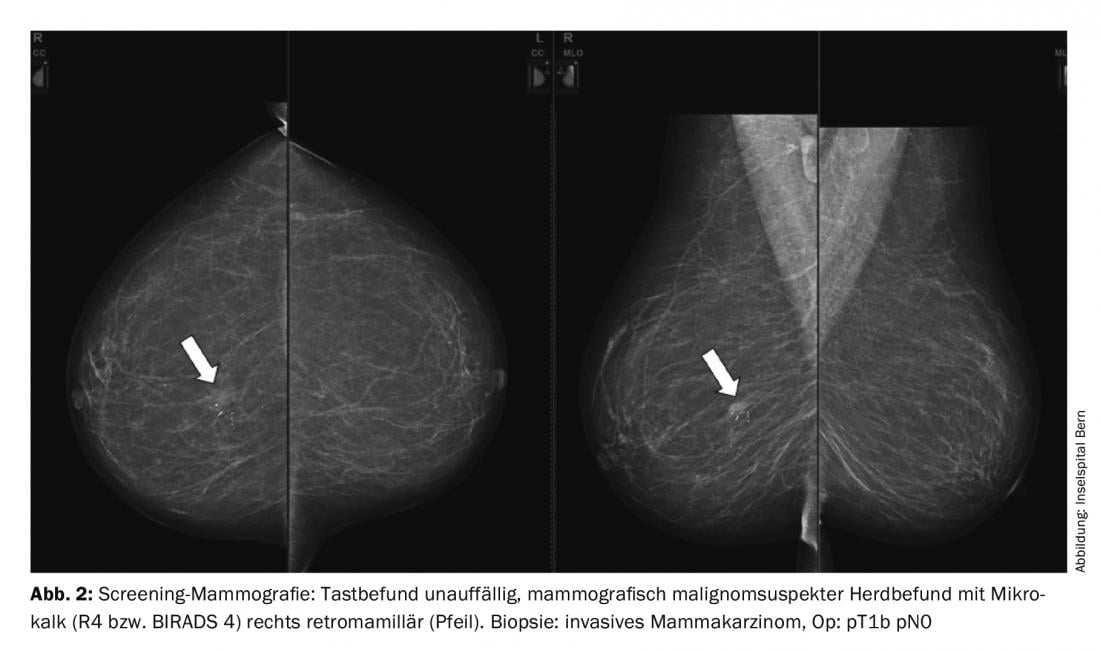

Conspicuous findings (Fig. 2) are marked in the report using a breast sketch. The report of findings also includes a grading of suspected malignancy and a specific recommendation for further evaluation of the findings. In most cases, a complementary sonography or an additional mammography special image is sufficient to classify the abnormality of the mammography as benign. If a suspicion of malignancy cannot be ruled out with sufficient certainty, a biopsy is usually performed. Depending on the detectability, this is most easily performed under sonographic control with punch biopsy, otherwise under mammographic-stereotactic targeting using vacuum punch biopsy. At the latest, the biopsy can be used to clearly determine whether the finding is benign or malignant, which then requires treatment.

MRI examinations are only required in individual cases. In the screening program, follow-up examinations at intervals of several months (“early recall”) should also only take place in exceptional cases in order to minimize the psychological burden on the women concerned. For this reason, the time requirements of the screening programs demand maximum time intervals of seven weekdays each between the screening mammography and the notification of the results, between the notification of the results and the offer of an appointment for any clarification diagnostics, and between the start of the clarification diagnostics and the final result.

Results

Between 1993 and 2016, approximately 1.14 million women participated in breast screening in Switzerland. Around 78% of all invited women regularly use this service [10] – this is a relatively high number compared to Europe. The average participation rate is about 40% [10].

In incorporated breast screening programs, approximately 10-15% of all mammograms come to a consensus conference. In about 5% of the participants, a supplementary clarification diagnosis is performed, with a biopsy in about a quarter of the cases. In the first round of invitations (prevalence round), breast cancer is detected in about six to eight out of 1000 participating women, and in subsequent rounds (incidence rounds), it is about three to four out of 1000 participants.

Long-term data on the effect of breast screening programs are not yet available for Switzerland. Final results regarding mortality from breast cancer can be expected in the respective programs from 15 years after the start of the program, when a cancer registry with as complete a record as possible of breast cancer cases in the canton also exists in parallel with the screening program. The latter is a prerequisite to detect the rate of so-called interval carcinomas. These are breast cancers that are clinically apparent between two screening examinations and thus may escape registration in the screening program.

Pending a final evaluation of the programs, so-called “surrogate parameters” are used to monitor success and for comparison with the values of other screening programs. Among the most important of these parameters are participation rate and cancer detection rate. If the participation rate is too low, there is already mathematically no effect on the reference population. The cancer detection rate is a measure of the sensitivity of the program.

Discussion

The utility of systematic breast screening programs is repeatedly questioned. Critical questioning of established opinions is definitely a basic principle of modern science. For laypersons and experts alike, however, it is always irritating how emotionally charged the debates are, how little transparency there is in the data material discussed, and how tendentiously the results derived are presented. Moreover, the arguments are regularly hijacked selectively by different interest groups for their cause. It is also striking that there are practically no actively working physicians among the screening opponents. The cornerstone of practical experience, which is otherwise so important for the medical profession, is de facto left out. The associations of affected women, on the other hand, such as Europadonna, but also national and international health authorities are clearly among the supporters of breast screening.

Balanced communication and information of the target group, but also of the rest of the population, is therefore an important cornerstone of all breast screening programs in democratic societies. In Switzerland, all eligible women receive a brochure with their invitation that follows these requirements. In addition, detailed and balanced information can be found on the homepages of the relevant Swiss organizations (e.g. www.krebsligaschweiz.ch; www.euro padonna.ch; www.swisscancerscreening.ch).

Take-Home Messages

- Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in women. One in eight women will develop the disease in the course of her life.

- In Switzerland, there are 5900 new cases and about 1400 deaths from breast cancer each year.

- The goal of systematic breast screening is to reduce mortality.

- About half of the Swiss cantons now offer a breast screening program.

- The discussions about the benefits of breast screening that flare up again and again are often emotional, and the motivations are difficult to discern.

- Fundamental requirements for a successful breast screening program are balanced communication, socially equitable accessibility, and adherence to the highest quality standards of implementation. Thus, a systematic breast screening program currently offers the best chance of reducing mortality.

Literature:

- BfS: Data on mortality and causes. www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/gesundheit/gesundheitszustand/sterblichkeit-todesursachen/spezifische.html

- National Cancer Program for Switzerland 2011-2015. Oncosuisse 2011.

- National strategy against cancer 2014-2017: annual report 2015. National Cancer Program for Switzerland. BAG 2015.

- Schopper D, de Wolf C: Breast cancer screening by mammography: International evidence and the situation in Switzerland. Krebsliga Schweiz/Oncosuisse 2007.

- Perry N, et al: European guidelines for quality assurance in breast cancer screening and diagnosis. 4th edition. European Communities 2006.

- FOPH: Ordinance on Quality Assurance in Breast Cancer Screening Programs (832).

- BAG: Directive on quality audits at mammography facilities (R-08-02).

- Brütsch U, et al: Quality standards for organized breast cancer screening in Switzerland. Krebsliga Schweiz 2014.

- Swiss Cancer Screening: Your Canton. www.swisscancerscreening.ch/kantone/ihr-kanton

- Swiss Cancer Screening: Monitoring Report 2012. www.swisscancerscreening.ch/brustkrebs/fachinformationen/monitoring

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2017; 5(4): 18-21.